Back to selection

Back to selection

Berlinale 2021: Mr. Bachmann and His Class, What Do We See When We Look at the Sky

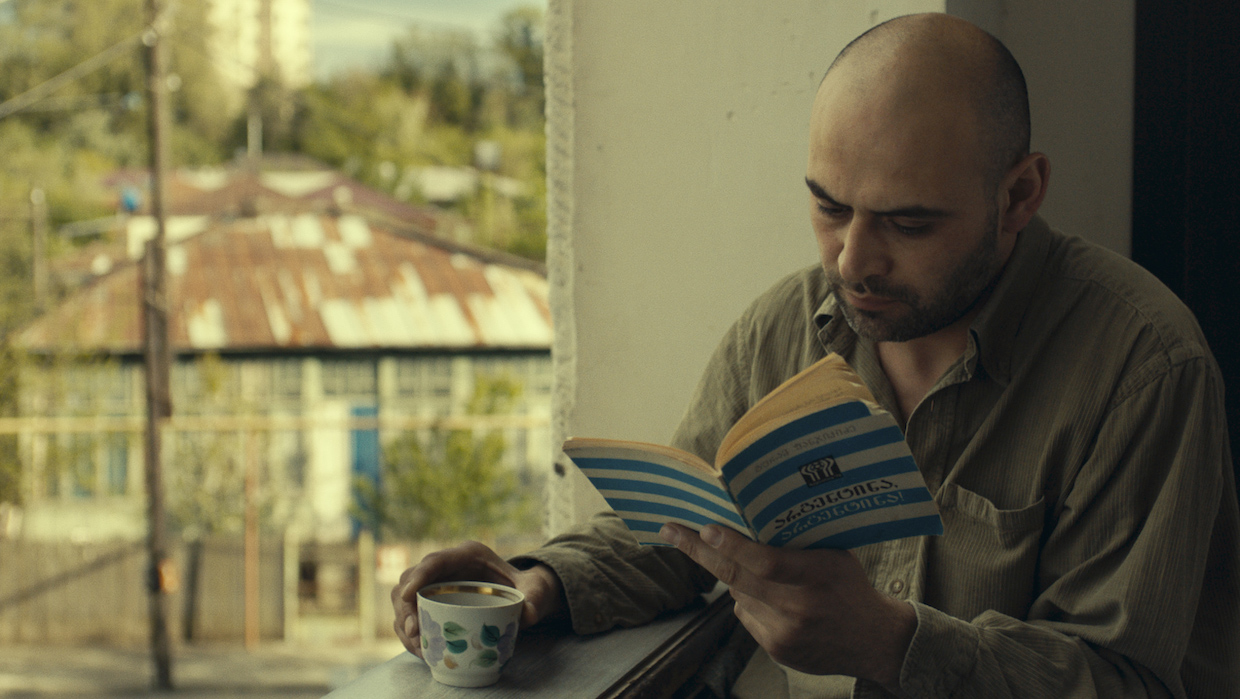

What Do We See When We Look at the Sky

What Do We See When We Look at the Sky The ongoing Berlinale is, as you’re likely aware, the first ever to be held virtually. Which also makes Berlin the first of the Big Three film festivals to go this route, seeing as last year Cannes was cancelled and Venice managed to squeeze in a smaller-scale edition between waves of this most pernicious of pandemics. Although the Berlinale has always prided itself on being a public festival, this time it’s a professionals-only affair—a repeat in the city’s cinemas, accessible to all, is planned for June—and the customary eleven days have been reduced to five.

Parsing the rationale behind this split and compression from the vague official statements has proven difficult, though it does seem like the films themselves are getting shortchanged. It’s inarguable that a cancellation of the behemoth European Film Market would have been disastrous for the films and the industry as a whole, but keeping the competitive dimension makes things awkward, given that the films thus relinquish their premiere status and, along with it, the possibility of competing in any other major festival. (German productions have a small advantage in this regard, since they can show elsewhere and be considered as international premieres, though the more prestigious festivals will still give them a pass, lest it should look like they’re picking up the Berlinale’s leftovers.)

Initially, when the new format was announced in December, it wasn’t clear whether the press would be allowed to participate in this first leg. A complete lack of coverage would have meant competitions taking place in a vacuum, with just the award winners receiving a bit of a publicity boost. At the last minute, the press was granted access after all. But even if you count only the seven sections dedicated to films that are new and feature-length, the program comprises more than 90 titles. Then there’s some 50 shorts and experimental films. Factor in all the by now familiar arguments against streaming, and it should be evident that this scenario is hardly ideal for the smaller and more challenging films—that is, the ones for which festivals are a lifeline.

Here I want to give a shout-out to Grandfilm, one of Germany’s most idealist distributors, who not only picked up two of the longest titles in the Competition, but also screened them in a cinema the week before the festival. Beyond gifting a few of us our first cinema visit since Berlin’s second lockdown started in November, they made sure we would see the films in the format their authors intended and with our attention undivided by emails, tweets, texts, calls, flagging bandwidths, postal deliveries, snack runs, needlessly indulgent toilet breaks and whatever else.

The first of these, clocking in at 217 minutes, is Maria Speth’s Mr. Bachmann and His Class, a documentary about a sixth-grade class in Stadtallendorf, a small town in the German state of Hesse whose population is predominantly made up of immigrants—something reflected in the composition of the class. Wisemanesque in her approach, Speth doesn’t directly provide contextual information (though several moments are too conveniently functional and/or symbolic to pass as unstaged). As such, it’s helpful to know going in that Germany has a three-tier secondary school system: on the basis of their academic performances students are split into Hauptschule, Realschule and Gymnasium, with only the last and most selective of these offering the possibility of graduating high school and attending university. Patently, it’s a system that fosters inequality by maintaining social divides, all the more perverse for imposing this categorization at such a young age. Secondary school starts after the fourth or sixth grade, depending on the state; in Hesse it’s the sixth, so this impending triage hangs over the film.

An early scene mirrors one in Eric Baudelaire’s Un film dramatique, also a documentary about a multiethnic class of young teens, though in France. Asked about their sense of belonging, all the kids in Baudelaire’s film are emphatic about being French, even if their parents were born elsewhere; posed the same question, not a single one of the immigrants’ children in Mr. Bachmann identifies as German and all expect to eventually return to their parents’ homelands. Further scenes, such as parent-teacher meetings and a school trip to a former Nazi forced labor camp, elaborate this political dimension, explicitly drawing a continuum from the exploitation of foreign labor during WWII to the Gastarbeiter (guest workers) of the postwar decades to the present.

What’s curious is that Speth frontloads her film with these considerations, then after an hour or so largely leaves them behind in favor of a more personal portrait, as suggested by the title. Mr. Bachmann, the class teacher, is an instantly familiar type of down-with-the-kids pedagogue: a 65-year-old who still wears AC/DC hoodies and knitted beanies, freely swears while talking to the children and will pull out a guitar at any given opportunity. He’s also very dedicated to his students and, some slips into sentimentality notwithstanding, the rapport between them is genuinely moving. Having shot what must be a staggering amount of footage over the course of a year with several simultaneous cameras, Speth’s skillful recreation of the dynamics of a classroom, as fueled by the explosive emotions of puberty, is never less than engaging. Still, it feels misjudged to begin a film by highlighting grievous systemic injustice and then divert into celebratory humanism. By the end, when the children graduate and go off on their institutionally circumscribed paths, the impression is that it’s Mr. Bachmann, alone and facing retirement, who’s suffered the biggest loss.

Given that Speth is one of the few Berlin School filmmakers who has yet to make a splash internationally, when her Competition slot was announced, I thought this was about to change. Now I’m not so sure. I expect that the forbidding running time, combined with its narrow local focus, will prevent Mr. Bachmann from doing for Speth what, say, The Dreamed Path and Western did for Angela Schanelec and Valeska Grisebach. On the other hand, I’d put money down on Georgia’s Alexandre Koberidze emerging as this festival’s big discovery—incidentally, What Do We See When We Look at the Sky is his graduation film at the DFFB, i.e. the original “Berlin school” and alma mater of Schanelec and co. His inclusion in the Competition makes for quite the ascent if you consider that his previous and first feature, 2017’s Let the Summer Never Come Again, is a 3.5-hour experimental docufiction shot with a low-resolution cellphone camera which premiered at the Berlin Critics’ Week, the small alt-festival that runs in parallel to the Berlinale (and this year is making a point of offering a public virtual program).

Although clearly born from the same sensibility, What Do We See is as idiosyncratic as it is polished, an assertive work whose stunning images, chiefly shot on 16mm by Koberidze’s classmate Faraz Fesharaki, are a far cry from the pixel soup of its predecessor. The film begins with a Bressonian meet cute, framing only the characters’ feet as they literally bump into each other in the street, then after a few steps turn around and bump into each other a second time. When their paths cross again that night, we see them in extreme long shot, barely visible, two specks in a gorgeous landscape of inky blues dappled with the orange glow of streetlights. By introducing his protagonists through this juxtaposition of extremes, it’s as if Koberidze were underlining that synecdoche isn’t limited to the signification of a whole through one of its parts—it can just as well be the opposite, and he spends the remainder of his joyful film exploring the possibilities that lie along this spectrum.

Plot is kept at a minimum and its synopsis would likely make most people run for the hills: after falling in love through the above chance encounters, Lisa and Giorgi arrange to meet the next day. But they are struck by an evil eye that transforms their appearances and when they show up to the date they no longer recognize each other. Giorgi gets a job outside of the café where Lisa works and they spend their days pining for one another, oblivious to the fact that they’re always within immediate reach. Despite the fairy tale premise and elements such as a talking rain gutter, the film is less an exercise in magical realism than an effort at drawing out magic from the mundane. To be sure, it’s drenched in whimsy, but it’s testament to the vitality of Koberidze’s vision that it never becomes cloying.

As in Let the Summer, Koberidze keeps the central romance in the background, returning to it at intervals, and instead focuses on the city—then it was Tbilisi, now it’s the quaint and picturesque Kutaisi—luxuriating in its tranquil rhythms and digressing into micro-narratives that are again elaborated by an omniscient narrator. Many of these are related to the FIFA World Cup, which is ongoing, with the whole town rooting for Argentina, or, more specifically, for Lionel Messi (who IRL has yet to win the cup, despite having won virtually everything else winnable for a footballer). We thus pay repeated visits to the different spots where people congregate to watch the games and get to know their respective traditions and habitués, human as well as canine. And in the film’s centerpiece episode we attend a children’s football match, where they emulate their heroes in a majestic slow-motion sequence scored to “Un’estate italiana”, the official song to the 1990 World Cup, whose overinflated sentiment is rendered irresistibly romantic.

The “COVID film” has already become a genre, one that for the most part has not borne amazing fruits (in this respect, a special mention is due of Radu Jude’s biting and hysterical Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, also in the Competition). What Do We See doesn’t fit the bill—there’s not a mask in sight—but still I can’t separate the intense longing it inspired from the current circumstances. I’m wholly indifferent to football but always enjoy the World Cup: the general enthusiasm is infectious, and it’s a fun excuse to get together and drink outdoors in the summer. The experience feels so remote right now and Koberidze’s images of sun-soaked conviviality appear positively utopian in the dreary context of a virtual festival. If you’re allergic to spoilers, stop reading here, though it should be obvious from the start that such a fable can only end happily: Lisa and Giorgi find one another and Messi leads Argentina to victory. As the narrator tells us, “Everything happened the way it had to happen.” Let’s hope his optimism is validated and that when the world gets to see this beautiful film, it will be in a cinema, the way it should be seen.