Back to selection

Back to selection

TORONTO: TRAVELING WITHOUT MOVING AT ‘WAVELENGTHS’

Wavelengths, the Toronto International Film Festival program that ferries viewers deep into the world of contemporary experimental film, celebrated its tenth birthday in 2010 and received a sweet birthday gift: A completely sold out first show. Even enthusiasts who had lined up more than thirty minutes early were turned away from the 200-seat theatre at the Art Gallery of Ontario (along with your loyal scribe and similarly surprised colleagues from The Film Society of Lincoln Center, the Pacific Film Archive and the Walker Art Center). It was an auspicious start to curator Andréa Picard’s extensive program of more than thirty individual pieces.

Experimental cinema is often neglected by mainstream/arthouse or narrative/documentary dialectics; it’s neither fish nor fowl. Yet it thrives in programs from Rotterdam to Berlin, from San Francisco’s Crossroads to New York’s Views from the Avant-Garde. This year, world-class work by female filmmakers Chris Langdon, Helen Hill, Elaine Summers, and Peggy Ahwesh at the Orphans Symposium were required experimental viewing. A sold-out show is a rare occurrence for any film at the well-organized Toronto International Film Festival, and for a program of avant-garde work, it’s remarkable.

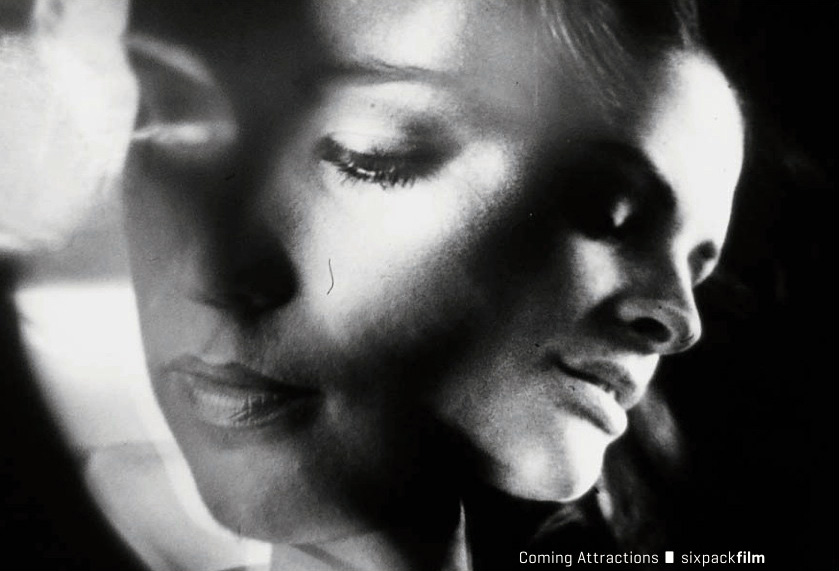

The ghostly realm of cinematic specters conjured by Peter Tscherkassky was among this year’s Wavelengths destinations. Tscherkassky, an artist who works exclusively on film rather than digitally, is a favorite among film programmers. Perhaps his most well-known piece is Outer Space, in which he re-purposed footage of Barbara Hershey in Sidney J. Furie’s The Entity (1981) and added a brilliant and buzzing score, thereby deconstructing the suburban-set horror movie into sensual and suspenseful building blocks.

Coming Attractions (2010), Tscherkassky’s first piece since Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (2005) screened in the program five years ago, arrived in Toronto straight after winning the Premio Orizzonti for Best Short Film at the Venice Film Festival. This ambitious 25-minute piece was inspired by film scholar Tom Gunning’s notion of a Cinema of Attractions which, according to Tscherkassky, “touches upon the exhibitionistic character of early film, the undaunted show and tell of its creative possibilities, and its direct addressing of the audience.” Describing his process for the French journal Trafic, he explained, “At some point it occurred to me that another residue of the Cinema of Attractions lies within the genre of advertising: Here we also often encounter a uniquely direct relation between actor, camera and audience. The impetus for Coming Attractions was to bring the three together: commercials, early cinema, and avant-garde film.”

The found footage in Coming Attractions was rescued from a bankrupt advertising firm and gifted to Tscherkassky, who immediately saw its potential. “It came to about six hours of rushes from commercials, some of them so bad that they never were used,” he explained to me. “It was like a raw jewel waiting to be polished.” He produced the labor-intensive piece over the course of two years, all the while maintaining the sensible practice of not working in the darkroom during summertime. For Tscherkassky, the notion of cinematic travel has been intriguing since childhood. “The very first film I ever saw and can still recall is Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (USA 1965),” he told me. “I loved it.”

Though originally intended as a gallery installation, it was valuable to view Hell Roaring Creek (2010) by Lucien Castaing-Taylor in Wavelengths’ theatrical framework. Comprised of a single long-take recorded on a static camera positioned mid-stream, the film opens on a landscape shrouded in darkness, accompanied by the noisy chatter and burble of the roiling Montana brook. Slowly, in real-time, sunlight suffuses the frame, and just when one has steeled oneself for a landscape marathon à la James Benning (whose demanding new film, Ruhr (2009), was presented solo in the third Wavelengths program), the lumpy shadow of a single horseman becomes visible, and then the silhouette of a sheepdog separates itself from the darkness. A single sheep gingerly wades into the river and miraculously creates a bridge across impassible visual space.

Another sheep fords the river, and then another until the procession of individual animals becomes a trickle emerging from one bank and disappearing from the frame when they reach the opposite shore. The flow increases, becoming itself a river of bleating forms. Lambs bound across in a giddy series of leaps, trying not to get their bellies wet; the larger ones are blasé; they’ve been through this before. The sheep wiggle and squirm on their short legs; as they try to keep their footing on the unseen stones below, they create an ovine traffic jam. Where have they come from? Where are they going? Viewers who have seen Castaing-Taylor’s feature film Sweetgrass (2009) — you can get a taste of its sumptuous visual style from this trailer — will have a context to put it all in. Otherwise, one can only intuit that the journey in Hell Roaring Creek is an ancient one; in an endless, existential sheep parade, the animals low softly in counterpoint to bells ringing softly around their necks.

A procession of ravaged signs, murals, and billboards form a visual patchwork in Thom Andersen’s Get Out of the Car (2010). Once and future graffiti abounds, and ingratiating sales pitches for long abandoned businesses provide come-ons to birds and tumbleweed. The piece’s excellent title comes from a Richard Berry song, part of a similarly patchworked soundtrack that includes musical snippets from Dexter Gordon to Woody Guthrie, along with the voices of locals who comment on the condition of their city as well as the dubious endeavor of the film itself. What emerges is a portrait of the city’s urban decay in all its seedy, ironic glory. Andersen is the filmmaker behind the epic Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) and, as he discussed in his own program notes as well as in Vadim Rizov’s also-well-titled essay, the city is a complex mini-galaxy he has studied for a long time.

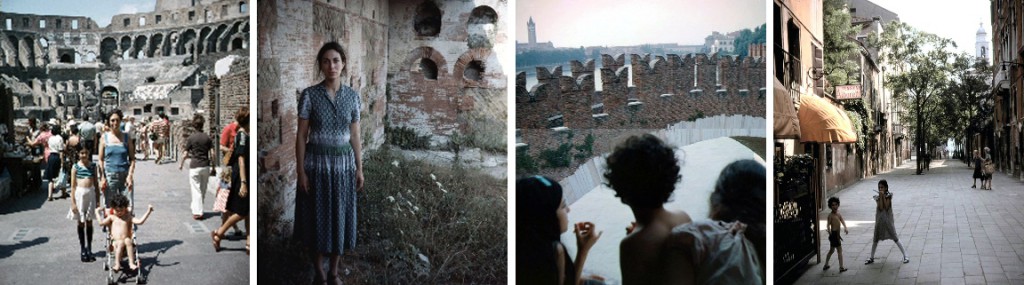

To end our little journey through this year’s Wavelengths are two tiny, silent stroboscopic pieces by Ken Jacobs. Jonas Mekas in Kodachrome Days (2009) is a lush, loving portrait of the charismatic founder of Anthology Film Archives, a fixture and patron saint of American avant-garde cinema and Jacobs’ longtime friend. More personal still, The Day was a Scorcher (2009) shares images from a family vacation to Rome during the early 1980s. (Jacobs’ son, Azazel, also used this close-knit family as the basis for cinematic exploration in his narrative feature Momma’s Man (2008) as well as more obliquely in The GoodTimesKid (2005), a film in which characters created a little family of their own.)

Ken Jacobs’ stroboscopic technique isn’t easy on the eyes. He isolates his foregrounds and then shifts the backgrounds back and forth, creating the jittery effect of a “Nervous Magic Lantern.” These shots are interspersed with frames of black, producing the illusion that viewer is moving through static images. (You can click here for a taste of his Eye Gouging Torture.) Occasional phrases augment Jacobs’ flicker films. “Life with a beautiful woman,” for example, precedes a detailed study of his wife, Flo. Jacobs studies the lovely, peaceful images of his family with proud and obsessive intensity. The group is slim and calm, exuding hippie street-cred. Although Jacobs himself is not shown in the photos, it seems likely that he was their photographer and that his subjects’ trusting gazes have taken on new significance for him now that time has passed. In The Day was a Scorcher, a voyage to the origins of familial mythology, Jacobs ruminates on the faces and bodies of his loved ones, as well as on the Italian settings that once cupped their fleeting, collective youth.

It’s quite a trip.

Special thanks to David Balzer and Susan Oxtoby.