Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance Notes: RISE to RUMBLE, must-see TV… from Canada

A still from VICELAND Canada's RISE, directed by Michelle Latimer. All photos below courtesy Sundance Institute. (Photo Michelle Latimer)

A still from VICELAND Canada's RISE, directed by Michelle Latimer. All photos below courtesy Sundance Institute. (Photo Michelle Latimer) Malcolm Forbes, of all people, once memorably said, “You can easily judge the character of a man by how he treats those who can do nothing for him.”

I’d like to extend that principle: You can easily judge the character of a nation by how it treats the indigenous people from whom it took its territory.

I’m from Chattanooga, near the Chickamauga battlefield, just east of the Ocoee and Hiwassee rivers, in the southeast corner of Tennessee. I grew up on an Appalachian mountain, dated a girl in nearby Ooltewah. I now live in Manhattan. All indigenous names.

Where are the contemporary indigenous populations to go with these names?

Trump’s immigration hysteria aside, from an indigenous perspective we are all immigrants. Perhaps that’s why no matter how gaseous or bombastic a U.S. presidential election grows, the one issue in national politics that is never, ever touched upon — as if radioactive — is the welfare and well-being of our fellow Native American citizens, who are not immigrants. They are instead simply invisible.

In the U.S. there are 50 states, as state-rights advocates are fond of applauding, but 567 federally recognized tribes, each of which counts as a sort-of sovereign nation (can’t print money). Per the Constitution however, tribal sovereignty exists as a third basic type of American sovereignty alongside the dual framework of separate state and federal powers.

So let’s assume, for argument’s sake, a past littered with 567 broken treaties between Congress, to whom the Constitution gives sole “power to regulate Commerce” with the tribes, and Native America. From a national politician’s standpoint, best not to step anywhere near this vast legal minefield. (Obama’s 2014 trip to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation was but the third visit of a sitting president to Indian country in 76 years, after Bill Clinton and FDR, who motored through Cherokee, North Carolina, on his way to Warm Springs, Georgia.)

After all, American Indians were not even U.S. citizens until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. That’s right — they got the right to vote four years after women did. Nationally, at least. Utah (named for the Ute tribe), home to Sundance, fought against the right of Indians to vote until 1957.

Remember the 2013 budget sequestration to cut “discretionary spending,” forced on Obama by John Boehner’s Republican Congress, under threat of shutting down the government? It pulled the rug out from under the Indian Health Services, to the tune of $800 million. With not a peep from any national politician.

You can easily judge the character of a nation…

All of this came flooding back while watching the world premiere of the first three episodes of RISE, VICELAND Canada’s new 8-part docu-series, in the Special Events* section at Sundance.**

Selected as part of the Festival’s new Climate Program, each 44-minute episode explores a current clash between American Indian tribes and corporate interests seeking to despoil sacred lands in an effort to profit from fossil fuel or mineral resources.

In Apache Stronghold, First Nation host Sarain Carson-Fox (Anishinaabe) takes us to the San Carlos Reservation east of Phoenix, Arizona, where local tribes have organized against a controversial 2015 federal land-swap that awarded the world’s largest mining company, Rio Tinto, rights to the block-caving of copper ore beneath Oak Flat in the Tonto National Forest on land sacred to the San Carlos Apache. What amounts to underground strip mining would result in a massive sinkhole, wrecked aquifers and water tables, and airborne toxic dust from waste rock and tailings.

Wouldn’t you welcome that into your neighborhood?

In Sacred Water, Carson-Fox takes us to makeshift encampments 30 miles south of Bismarck, North Dakota (named for the Dakota Sioux), along the incongruously named Cannonball River, the northern border of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and site of last year’s Dakota Access Pipeline protest.

There we cringe as Energy Transfer Partners bulldozers callously tear open ancestral burial sites as pained protesters look on. Blasts of freezing water, streams of tear gas, and rubber bullets fail to turn back determined “water protectors.” At the same time, we are inspirited by the purpose and sincerity of the young Lakota and Dakota activists we meet, committed to non-violence, who were the very first to sew the seeds of the protest and who continue to enlist 21st-century social media to organize, document, and inform the world about what is happening at Standing Rock.

Part 2 of the report from Standing Rock, Red Power, looks back at antecedents to the Dakota Access Pipeline standoff — Alcatraz in 1969, Wounded Knee in 1973 — and updates us with footage of the arrival of a contingent of veterans in support of the movement, the ballooning of the camp population past 10,000, the exhilaration felt when the Army Corps of Engineers refuses ETP a permit to continue the pipeline, and the dark clouds gathering as an incoming President vows to undo the selfless sacrifices of so many.

Sure enough, on February 1, Trump ordered the Army CoE to reverse it’s decision and to greenlight embedding the pipeline under the Missouri River (named for the Missouri people). If ever there was a story of a struggle “to be continued,” this is it.

I had originally intended to review these episodes of RISE in a blog from Sundance, but Mike Hale of the New York Times beat me to it with his superb television review, which appeared one day before the Jan 27th premiere of RISE on VICELAND.

VICELAND, if you’re not familiar with it, is a new cable channel launched a year ago by VICE Media and A+E Networks under the creative directorship of Spike Jonze, who, when the channel was announced, remarked that “if [a production] doesn’t have a strong point of view then it shouldn’t be on this channel.”

All major cable providers now carry VICELAND. The initial episodes of RISE discussed above are now in rotation, with an additional five episodes on the way. So go ahead, set your TiVo right now.

RISE is a co-production of VICE Canada, Rogers Media, and the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN). Regarding upcoming episodes, VICE Canada describes RISE as an “immersive documentary series that will take us to the frontline of global indigenous resistance,” and so far this is exactly what director and showrunner Michelle Latimer (Métis/Algonquin) — a filmmaker whose work has been repeatedly invited to the Sundance Film Festival — has delivered.

Finally, in the end, what separates RISE from other documentaries about indigenous struggle is that not only are its creators Native American/First Nation, but the stories they tell convey a Native world view. There are no white authorities or talking heads. Hardly any white faces at all.

In one brief exception to this, towards the end of Red Power, an unidentified veteran prostrates himself before Standing Rock elders in a “forgiveness” ceremony, then eloquently apologizes for the U.S. Army’s crimes of massacre.

He is none other than the son of former NATO Supreme Allied Commander of Europe and presidential candidate General Wesley Clark. Dressed in his own dark blue U.S. Army Service Uniform jacket and matching Stetson calvary hat, Wesley Clark Jr. looks as if he’d just stepped out of the 19th century Indian Wars. But no lower-third title identifies him. This is not his story.

For if indigenous people can’t be entrusted to tell their own story, who can be?

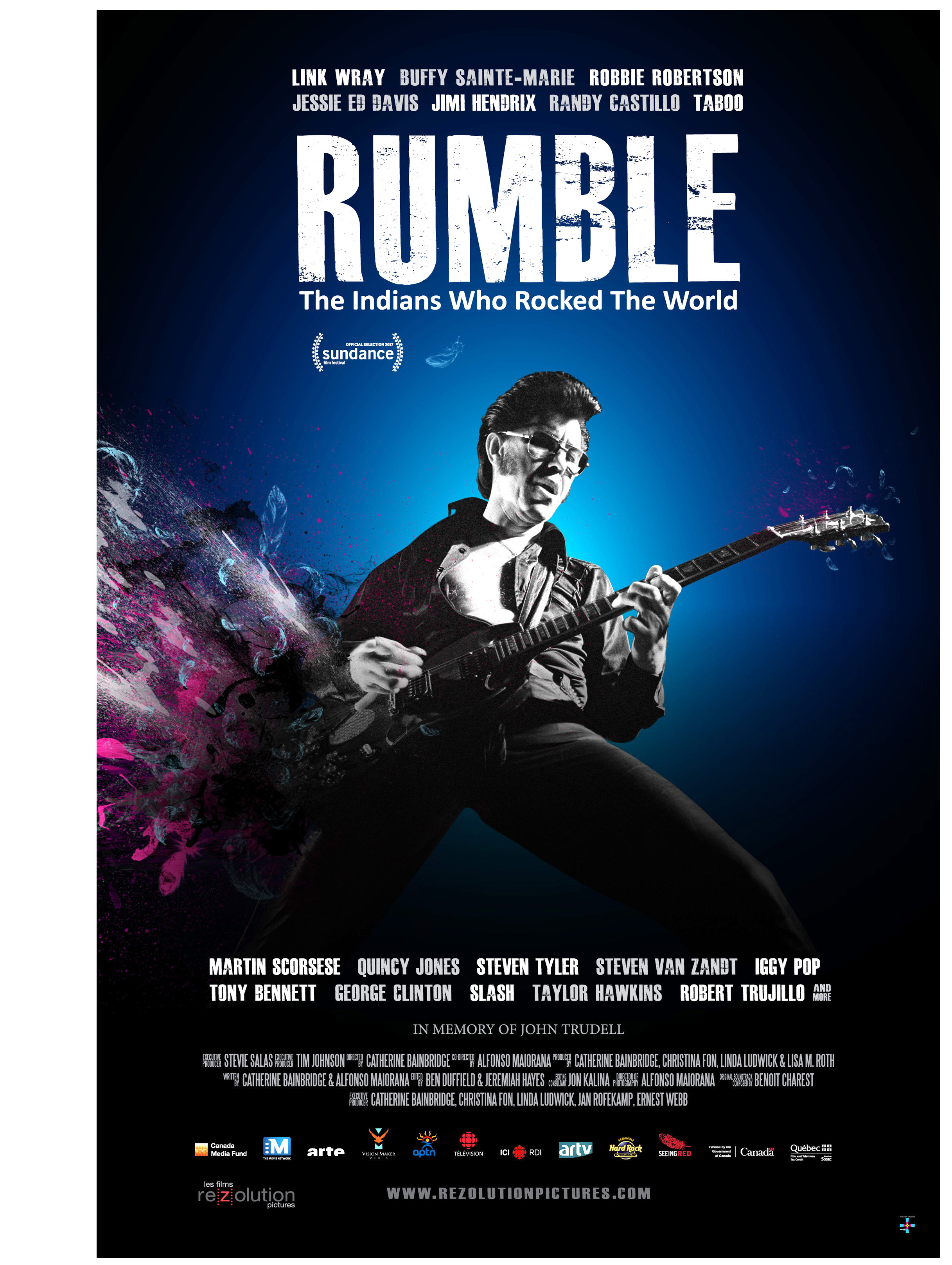

RISE was one of nine indigenous-made premieres at Sundance this year. One of the most entertaining of these, no less thought-provoking — also from Canada — was the documentary RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World.

The film’s premise is that the foundational contribution of Native Americans to American popular music is a “missing chapter.”

Musicologically, this is a lot to bite off. The canon of American popular music is vast, its influences and genres myriad: European Romanticism, Scotch-Irish jigs, African-inflected spirituals, West African polyrhythmic drumming, Minstrel shows, Ragtime, Cajun, Blues, Russian and Central European cantors, Bel Canto, Yiddish theater, Vaudeville, Tin Pan Alley, Country Western, Big Band Swing, Hollywood musicals, Broadway theater, Rockabilly, the Brill Building, Cuban, Tejano, etc. And that’s before the amplified rock era of the late 1960s, and all that followed after.

What I think RUMBLE achieves instead, with its lineup of rock musicians and pop-cultural arbiters like Martin Scorcese — and this is no less significant — is a closer look at what ten or so musical artists, some iconic, have given to pop music because of their Native ancestry — an overdue acknowledgment of what, in most cases, had always been hidden in plain sight.

RUMBLE takes its name from Link Wray & The Wraymen’s 1958 rock ’n’ roll classic, Rumble, the first “power chord” electric guitar instrumental to flaunt reverb and distortion. Its ominous tone and slow, strutting cadence — all switchblades, greasy ducktails, motorcycle jackets — got it banned from radio play in New York and Boston. No less than Pete Townsend, Jimmy Page, and Neil Young cite Wray (Shawnee), raised dirt-poor in North Carolina, as their major guitar inspiration.

Canadians Buffy Sainte-Marie (Piapot Plains Cree) and The Band’s Robbie Robertson (Mohawk) have always embraced their Native ties, although it was a revelation to learn that Robertson’s extended Mohawk family was filled with musicians who molded him musically. More edifying were sections detailing a direct Native influence on Mississipian Charley Patton (part Cherokee or Choctaw; state named after Anishinaabe word for Great River), considered “Father of the Delta Blues” and mentor to Howlin’ Wolf; on 1930’s jazz singer Mildred Bailey (Coeur d’Alene), who Tony Bennett acknowledges, on screen, “completely influenced” him; and on the harmonies of Southern spirituals, as demonstrated by Rhiannon Giddens of the Grammy Award-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops with members of Ulali, a Native American women’s a cappella group.

RUMBLE was directed by Catherine Bainbridge, who previously co-directed Neil Diamond’s (Cree) Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian, which was broadcast in 2010 on PBS’s Independent Lens. She also executive-produced 26 episodes of the Canadian TV series Mohawk Girls, described by IMDb as “a half hour dramatic comedy about four young women figuring out how to be Mohawk in the 21st century.”

Like the RISE series, RUMBLE was made in collaboration with the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN). Unsurprisingly, several of the same interview subjects appear in both, like the late Native American poet and activist John Trudell, to whom RUMBLE is dedicated. RUMBLE likewise concludes at the site of the Dakota Access Pipeline protest, using footage similar to RISE, only with the indefatigable Buffy Sainte-Marie, guitar in hand, serenading her encouragement to the protesters, as if the 1960s had never ended.

At the Awards Ceremony concluding the 2017 edition of Sundance, the documentary jury presented RUMBLE with the World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award for Masterful Storytelling.

I, for one, will never listen to Link Wray the same way again.

Footnotes:

* The Sundance Film Festival describes its Special Events section as “A celebration of the evolving landscape of content consumption… new voices in the medium, defying broadcast boiler plates with a redefinition of traditional episodic conventions.”

Boiler plates? That struggle is over. Think Girls, Baskets, Broad City, Mr. Robot, Insecure, Orange is the New Black, Fresh Off the Boat, Atlanta, Shameless, Transparent, Better Things, Speechless, Portlandia, Weeds, The L Word, Master of None, Jane the Virgin, Ugly Betty, High Maintenance, BoJack Horseman, and countless others.

That these are mostly cable, not traditional broadcast, is besides the point. The cultural needle in the U.S. got moved, in large part thanks to Sundance.

Whatever the future of media has in store, it was 33 years ago — long before episodic TV and cable exploded with intelligent writing and directing — that the Sundance Institute introduced what would become the Sundance Film Festival to showcase independently produced American films by courageous young directors of vision, especially from underrepresented groups. “New voices” that would not otherwise be heard.

To its lasting credit, special support for Native American and indigenous peoples — a cause dear to founder Robert Redford — was woven into the Institute’s fabric at the outset. Filmmakers Larry Littlebird (Laguna/Santo Domingo Pueblo) and Chris Spotted Eagle (Houmas Nation) participated in founding discussions, and for a while Native films even had their own Festival section, the Native Forum (withdrawn in 2004 over concerns of ghettoization).

Thankfully, the Institute’s Native American and Indigenous Program continues to thrive in the capable hands of director N. Bird Runningwater (Cheyenne/Mescalero Apache).

But here the cultural needle snagged.

Try to think of a single American episodic, comedy or drama, built around the daily lives of American Indians, of any tribe, in or out of Indian country. Or of a single Native American lead, male or female, on American TV or cable. (I mentioned, above, RUMBLE director Catherine Bainbridge’s credit as producer of 26 episodes of a 1/2-hour Mohawk comedy on Canadian TV to underscore this point.)

The homicidal outlier Hanzee Dent of FX’s Fargo — played by Zahn Tokiya-ku McClarnon (Hunkpapa Lakota), who also has a current role as a tribal police chief in Netflix’s Longmire, itself set against a fictional Wyoming county filled with Crow and Cheyenne secondary characters (the lead character is white however) — or Sheila’s boyfriend Roger Runningtree (Eloy Casados) in the fourth season of Showtime’s Shameless — these hardly count.

How about something like Donald Glover’s Atlanta but with an all-Native cast, set near Navajo Mountain or atop a Hopi mesa? Or even a lightly fictionalized telling of the running conflict between unarmed water protectors and armed police at Standing Rock, à la Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool?

Speaking of an evolving landscape of content consumption, perhaps it’s time for Native dramatists in the U.S. to seize the moment online — web series, anyone?

** For what it’s worth, The Sundance Institute and Sundance Film Festival get their name from the Sundance Mountain Resort, acquired and named by Robert Redford in 1969, the same year Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was released. Redford has said that the resort was not named for his role in the film, but instead his reverence for the Plains Indian’s sacred Sun Dance, banned in the U.S. until the late 1970s. The real Sundance Kid, train-robber Harry Longabaugh, acquired his nickname from a jail stint in Sundance, Wyoming, a town named for… the Plains Indian Sun Dance. In either case, another indigenous footprint in the sands of American vocabulary.