Back to selection

Back to selection

Cinema, Chimera: Maya Dardel Director Zachary Cotler on the Present Value of Difficulty

A Critically Endangered Species

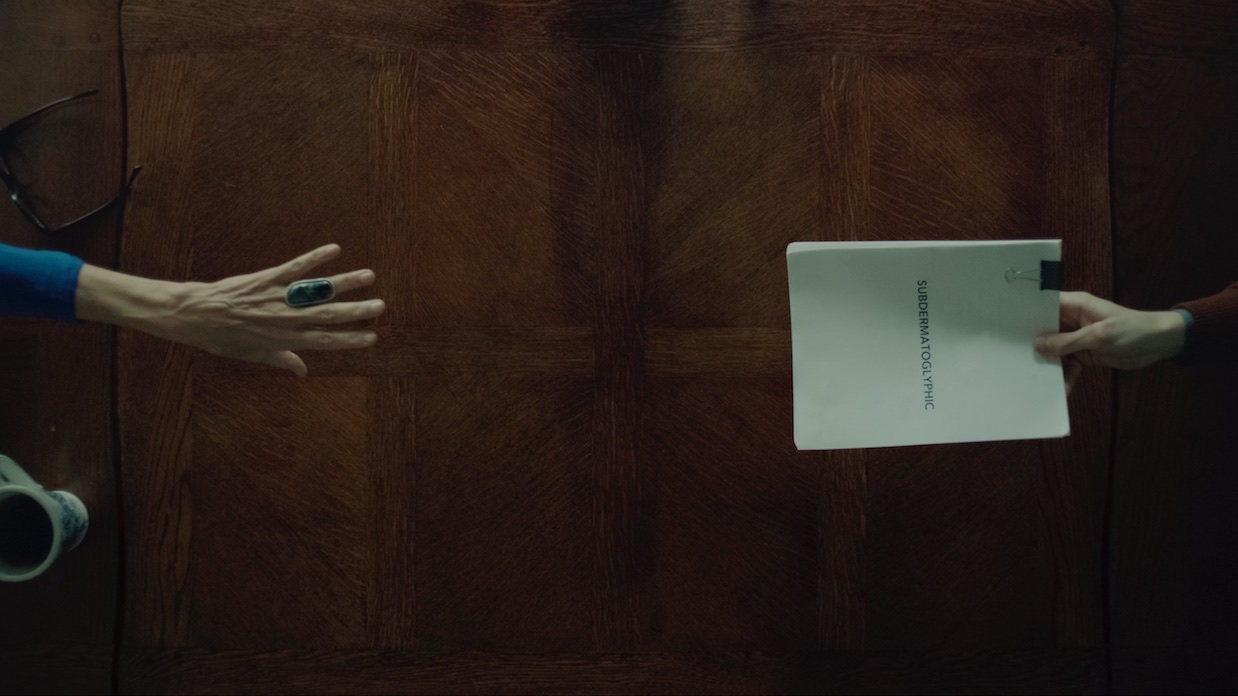

A Critically Endangered Species Set in the literary world and dealing with a dying poet and novelist with an unusual end-of-life proposal, the Lena Olin-starring Maya Dardel is directed by two filmmakers who know something about the world of their film. Magdalena Zyzak wrote the recent novel The Ballad of Barnabas Pierkel as well as co-wrote and produced the feature film, Redland. Zachary Cotler is the author of five books of poetry, fiction and literary criticism, and is a graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. In advance of their film’s premiere at the 2017 SXSW Film Festival, they’ve each penned an essay inspired by thoughts on the difference between creating literature and directing a film. Below is Cotler’s contribution. Read Zyzak’s here.

Sometimes the goat’s head is biggest, sometimes the lion’s or snake’s. Image-minded filmmakers abound; sound-minded filmmakers exist (unsound, too). For me, though music and image are not to be neglected, the unglamorous goat of language/character must lead. Because the human mind and lifespan are woefully limited. Career zoologists somehow never make the Olympic fencing team. Writing a story is nothing like photographing one or composing a score.

So my concerns (and any authority I may dubiously claim after making one feature film) as a director are writerly. I like to think I think a little like the Elizabethan poet, who perforce was, too, a dramatist, for whom costume and scenography could never bear the lion’s share of weight, because technologies of language in the late 16th century still so demonstrably surpassed technologies of image.

This is no longer the case, except in my head and heads of individuals who share my misfortune of language-mindedness in the age of social networking. Language today is arguably a technology in decline — not so the myriad technologies of image. Poor Christopher Marlowe, carried screaming from the pub, dagger-wounded in the head.

Anyway, I see films as fictions and make them like fictions and therefore linguistic “difficulty” is a concern. The Elizabethans were difficult. Joyce was difficult. In this company, the densest-woven screenplays of all time are “easy” texts. Cinema is a mass medium. It should be somewhat “easier” than literature. It also encourages political message-mongering. But politics and art traditionally degrade each other’s quality when forced to share a heart. Except perhaps when an artist remembers that to make art at all is already a potent political act.

Which brings us to our present chaos, in which, if it is possible to be heard above the cacophony, I’d like to say something to screenwriters, directors, novelists, playwrights, poets:

Art, fictional narrative especially, finds itself grazing in fallow terrain when the utterly preposterous replaces mundane reality. What are the meanings and purposes of fiction when mere reportage is less plausible, more sensational, than fiction? There is, however, one encouraging development: Trump, with his particular syntax and vocabulary, has rendered absurd, even obscene, for the foreseeable future, any claim that linguistic or thematic difficulty is at all complicit with power and elitism. Art’s function has long been resistance to dominant modes and accepted standards. In Trump’s moment, perhaps art’s most meaningful avenues of resistance are complexity and anti-anti-intellectualism (not to be confused with simple intellectualism). A complete, complex sentence, full of willful nuance and allusion to older art, informed by genuine science and/or history, is the polar opposite of the Trumpian fragment, and thus, for the moment, the opposite of complicity with power.

That’s a long way of saying: I’d like to see (and make) more difficult films (and books).

(Editor’s Note: This post has been amended to note the film’s title change from A Critically Endangered Species to Maya Dardel.)