Back to selection

Back to selection

“It Just Wasn’t Easy to Set Up a Movie About a Murdered Atheist”: Tommy O’Haver on The Most Hated Woman in America

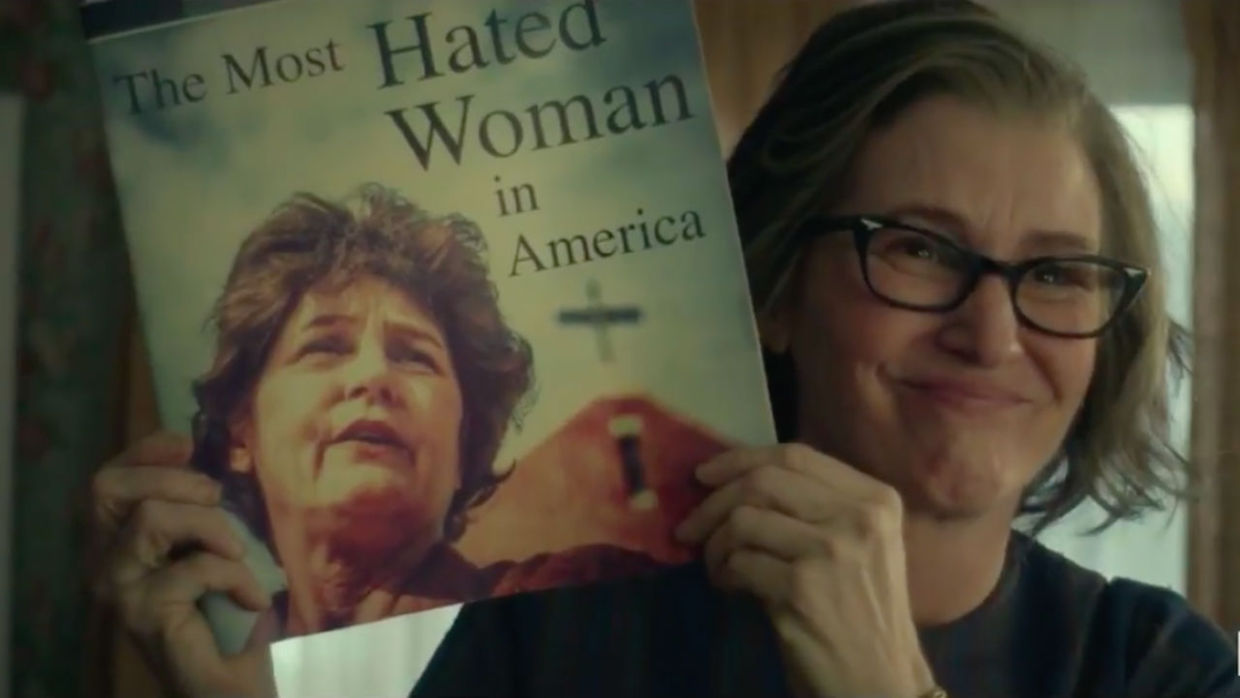

Melissa Leo in The Most Hated Woman in America

Melissa Leo in The Most Hated Woman in America The media dubbed her “the most hated woman in America,” and famously eccentric atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair wore that claim like a badge of honor. As played by Academy Award-winner Melissa Leo, O’Hair was an outspoken but noble mother who stood for her family’s First Ammendment rights in providing a voice to the voiceless. Protesting for basic civil rights with local African-American men and women and fighting back against the practice of prayer in public school, O’Hair fought very loudly against religious and anti-constitutional rhetoric beginning over fifty years ago. Her impact remains: the non-profit organization known as American Atheists, founded by O’Hair, is still in operation.

In spite of these accomplishments, O’Hair was not well loved. With her rise in popularity came hate mail, severed relationships, personal greed, and a kidnapping that left her and several family members dead. She was a controversial figure both for her larger-than-life public persona and for her shady and unethical behavior in private. Told simultaneously as a maternal origin story and as a thriller involving an extending kidnapping in a dank hotel room, Tommy O’Haver’s The Most Hated Woman in America documents a woman who fought for her beliefs and unexpectedly died for them too.

In advance of the film launching on Netflix today, I spoke with director Tommy O’Haver about the long journey involved in bringing the wild-but-true life of O’Hair to fruition, the dangers involved in reaching out to real life characters you’re depicting on screen, and making a period piece on a tight budget.

Filmmaker: Before embarking on this project, how familiar were you with the life of Madalyn Murray O’Hair?

O’Haver: To be honest, I wasn’t really familiar with her at all. Elizabeth Banks and Max Handelman, the producers on this film, had seen An American Crime, a film I had at Sundance some years ago, and approached my writing partner, Irene Turner, and I with this story. When we dove into it, I couldn’t believe that I had never heard of this woman and that I didn’t know this crazy story. This was like seven years ago, and I’ve gotten to know her quite well in the meantime.

Filmmaker: So you were trying to make the film for seven years?

O’Haver: We wrote the first draft of the screenplay seven or eight years ago, but it just wasn’t easy to set up a movie about a murdered atheist. Over the last several years I did some staged readings and sent the script to Melissa Leo pretty early on; she signed onto the project five years ago after reading one of the first drafts. I wrote and re-wrote the screenplay so many times, and we did so much research. There was an enormous amount of material about Madalyn, both in her own writing and articles about her, [not to mention] her numerous television appearances. It was seven years of off-and-on writing and rewriting until Netflix got involved.

Filmmaker: Madalyn was obviously someone with a very strong personality and message, and the film shows her undying support for atheism through her championing of the First Amendment and the creation of American Atheists in Austin, Texas. How much of a tightrope did you have to walk between crafting a film about a character with a message as opposed to making a “message movie” yourself?

O’Haver: While I totally support Madalyn’s fight for the First Amendment, I don’t consider myself an atheist in any way. I never thought of it as a message movie. It really started as a great “true crime” story and what attracted Irene and I to the project was the complicated character at its center. She’s just wonderful and horrible all at the same time. She’s surrounded by all of these crazy, unusual characters too. That’s what it became about [for me], to try to create a good character sketch of this complex woman, with all of her faults, and try to make you feel a little bit for her by the end. Even though she is the “most hated woman in America,” perhaps there’s a little part of her you could love by the end. We’re most interested in really good characters and what drives them.

Filmmaker: Madalyn went through many odd encounters due to her message, including when, as the film depicts, a man dressed as Jesus attempted to assassinate her outside of a radio studio. How did you choose which outlandish encounters to feature in the film?

O’Haver: It’s hard to say. Madalyn had given such great quotes, for example, and one of the hardest things was choosing which to use in the movie. And regarding the events we depicted in the film, there’s obviously some extrapolation going on. It’s important to remember that it’s not a documentary. Over time, Madalyn’s relationship with her son began to rise to the surface as something that was very important. I began to see the story as a quintessential tragedy about a woman whose hubris gets in the way of her message and ultimately drives her to push away the people she loves the most. That emerged over time. When she’s in that hotel room, kidnapped and held there — we don’t even include all of the weirdest stuff in the movie, because audiences wouldn’t believe it. She’s not sure if she’ll ever get out of that place alive. I saw it as a crisis of conscience about her family and her son, Bill Jr. She made some mistakes with him, regretted those mistakes, and thought “maybe I can make this right.” By the time she realizes that, it’s too late.

Filmmaker: That’s a very prominent member of the Murray O’Hair family that’s still alive, Bill Jr. The viewer sympathizes with him throughout the film, but the update we receive by the closing credits shows he’s taken on an initiative quite different than his mother’s. Did you ever attempt to reach out to him or anyone else in close proximity?

O’Haver: No, and part of it is because you’re creating a work of fiction centered around a true story. Sometimes when you speak to these people, they may not remember things exactly as they took place. Bill Jr. had been published quite a bit and had done many interviews, so a lot of the things we took were things he actually said. I have to be careful about getting people like that involved. The first thing they’re going to try and do is say “Well, this is how it really happened,” and then you run the risk of being hijacked.

Filmmaker: If you have to follow everyone’s version of the story, you’re going to be left with a bunch of different versions.

O’Haver: Yeah, and the interesting thing is that both Madalyn and Bill, Jr. wrote quite a bit about each other, and their two stories are very different. He would talk about what an awful mother she was and she’d talk about how wonderful of a son he was. You have to imagine that the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

Filmmaker: The narrative takes a interesting form, continuously toggling between the rise of Madalyn’s cause and her kidnapping in San Antonio in 1995. The story isn’t told in a linear fashion, nor is it bookended by the typical “character reflecting on an important moment in their life” approach. How did you arrive at telling the story with two narrative throughlines?

O’Haver: From the very beginning that just seemed like an obvious approach. The kidnapping plotline was interesting, but you needed some context. Because our budget was so low, if I could have done it, I would have shot the entire film in the hotel room, but there was no way to really do it like that. You needed to tell people who this woman was and why we should care. From there we checkerboarded what we wanted to reveal when, and so forth. The other interesting thing was the investigation [strand of the story] featuring Adam Scott’s character. We took some liberties there. A lot of people attribute the investigation to this real reporter, John MacCormack, but that didn’t really start until a year after the family disappeared. It was so much more complex, and featured even more reporters and the IRS getting involved. They didn’t uncover their bodies until 2000 or 2001. It was a very complicated and drawn out process. For narrative purposes, when you’re telling a story in ninety minutes, you need to condense and simplify, and so we had to make Scott’s reporter character [tracking the disappearance of O’Hair] a composite character. It was a good choice though because it helped to drive the narrative toward key points. The most important stuff rose to the surface and it was a matter of trying to keep things moving with his partner-in-crime.

Filmmaker: Because of this approach, we keep checking in with the characters at various stages in their lives. I imagine the makeup and hair design for Melissa Leo was particularly thought-out?

O’Haver: It was, and again, we were on a very limited budget. Koji Ohmura came up with this very simple prosthetic for her. We had an eighteen day shoot, and so we didn’t have the luxury of shooting all of her “older scenes” at one specific point in the schedule. There were some days where Melissa was playing two or three different ages on the same day. It was intense. I wanted to keep the aging makeup pretty simple and as subtle as possible. Koji came up with some simple ways to do it [that weren’t distracting].

Filmmaker: And since you’re jumping between so many different time periods at a rapid pace, did you work with your cinematographer Armando Salas on establishing a visual identity between decades?

O’Haver: Definitely. Everything that’s set in the late 1990s, aka the present, was shot handheld. It’s very subtle, but it’s there, and with a more video texture. A lot of this we did in post, in terms of texturiziing (we shot on an ALEXA Mini), to differentiate between the unique stages in time.

Filmmaker: As Madalyn was a big media personality, making several notable guest appearances on late night talk shows (The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson being the most prominent), the film integrates Melissa Leo directly into archival footage; you incorporate a shot-reverse shot interview between Leo and Carson, for example. What precautions do you take to make the previously shot footage visually match with your’s?

O’Haver: That was probably the most difficult thing [to pull off]. There are some times where I’m like “Well, I wish we could have gotten that even better.” What we were doing with this film was so ambitious for the budget, let me just put it that way. I brought on an archival researcher pretty early in the process. I pushed for that because I needed to know exactly what I was going to be trying to match to. She would send me the material and I would show it to Armando and my production designer David L. Snyder. We’d talk about “OK, this is the one thing we need to pick up with Melissa Leo so that we can integrate it into the archival material as seamlessly as possible.” We’d then shoot the scenes with Melissa, and then in post with the visual effects people, you meddle with it over and over again until it matches as best it can.

Filmmaker: How did Netflix come aboard the project?

O’Haver: Elizabeth Banks and Max Handelman had gone to Sundance two years ago and gave the script to Netflix. We’d be pushing for years, sending it to independence financiers, but it was hard to find independent financing for this unusual story. Netflix read the script and really liked it. They were experiencing a lot of good press for their “true crime” projects and had developed an audience for that kind of material. Once a deal was nailed down and we started to move into production, they were pretty hands off. They gave us the money and said that they wanted to be kept in the loop as to who we were casting, but they trusted Elizabeth and me in who we were coming up with. When we finished the movie and they took a look at it, they liked the first cut and gave us some notes. We did three passes for them (in terms of notes) but it was pretty minor. It was a great creative experience in that sense, and it’s unusual in that we are going to reach a huge audience on there, that’s for sure.

Filmmaker: And watching it now as the First Ammendment is being discussed on a daily basis, I’m sure there’s some unexpected topical relevance as well.

O’Haver: There’s definitely some relevance there that we’re seeing happening. If audiences take away anything political from the film, I just hope they don’t take for granted our First Amendment rights.