Back to selection

Back to selection

Check Your Canon

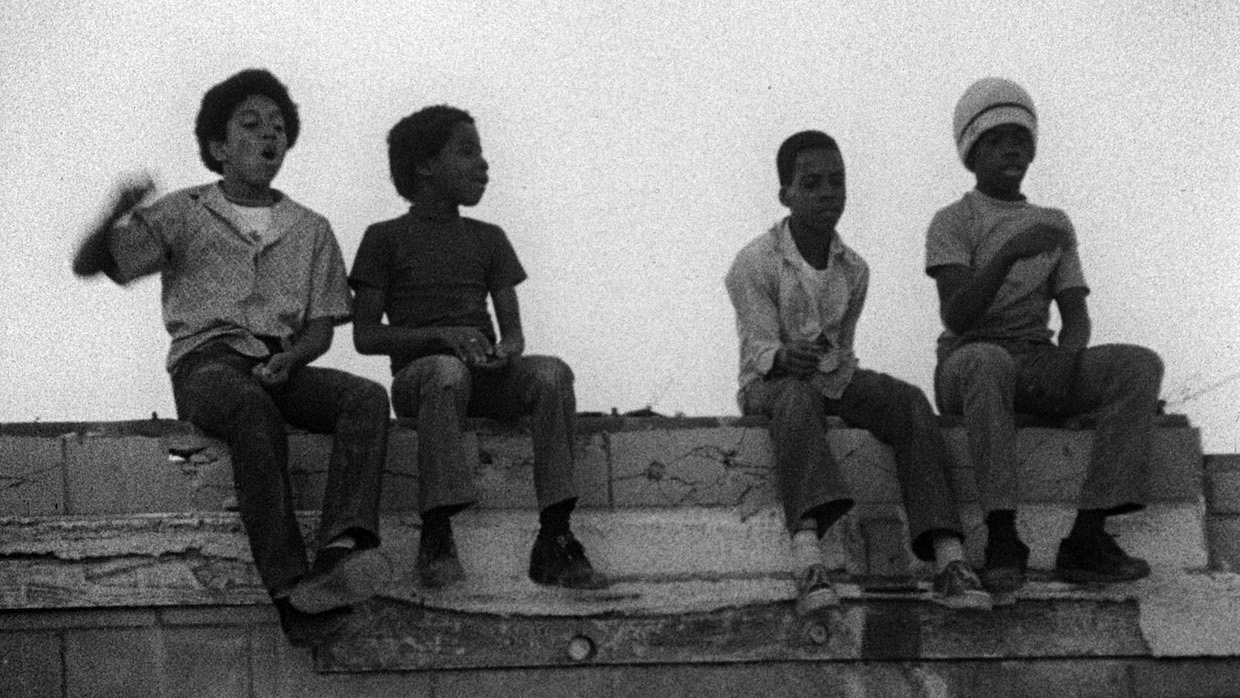

Killer of Sheep (Photo courtesy of Milestone Films)

Killer of Sheep (Photo courtesy of Milestone Films) The issue of diversity in the film canon — the movies celebrated and studied at film schools across the country — has come under hot debate in the past couple of years, with students starting conversations about the larger consequences of curricular omissions. “When I look at a syllabus and there’s no one from my perspective on there, I wonder if my ideas will be taken seriously by Hollywood or by any producer,” admits Zsaknor Powe, a junior studying film at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. “It really affects the artistic self-esteem of the students,” explains Powe, whose Black southern male perspective — and, basically, any perspective other than a straight white hetero cis male point of view — is rarely reflected in the cinema shared in required courses.

But maybe film programs around the country are finally starting to listen to concerns like Powe’s. University of Southern California, for instance, is revising the list they send to incoming students, “100 Films To Watch Before Starting the USC Program.” And the theme of this year’s University Film & Video Association (UFVA) conference is “Media Diversity: Inclusion and Convergence.” These conversations taking place within film schools and intercollegiate organizations feel connected to larger movements calling out normalized white supremacy in the university system and Hollywood, but many emerged independently. For example, before “Racism Lives Here” became a rallying cry at University of Missouri and #OscarsSoWhite flooded Twitter, film student Gisela Zuniga started Radical Artists Aiming for Diversity (RAAD) at NYU’s Tisch at the beginning of her sophomore year in fall 2015.

RAAD, an official, student-run club, states its mission is “to promote an inclusive environment at Tisch…where [students of color] cannot see ourselves in our teachers, in the art work we study or in our classmates.” While advocating for curriculum changes, a more diverse faculty and a film mentorship program, the group offers a supportive network for black and brown students who often feel alienated in majority-white majors. RAAD has participated in the school’s listening session on diversity and inclusion and organized an installation in the lobby of the Tisch building asking students to record their experiences based on prompts like “Have you ever seen yourself represented onscreen in class?” While Zuniga notes that not all students and faculty have welcomed her provocations of the status quo, small steps have been made: The faculty has hired more instructors of color, and all instructors are given more diversity training. “Whenever a teacher or an administrator in the film program runs into me, they tend to tell me updates like, ‘We’ve hired four more faculty of color,’” recounts Zuniga, which speaks to the influence she’s had at Tisch, but also to white fragility, in the sense of a deep need for validation for overdue micro-progressions. “I’m like, that’s awesome but do you want me to congratulate you? Do you want me to give you a high-five?”

“Obviously, academia moves slowly,” reminds Norman Hollyn, a professor at USC Cinematic Arts and president of the University Film & Video Foundation. At USC, faculty and administrators started making changes a little over a year ago, and like at NYU, the impetus was student pressure. Hollyn notes these include “the formation of inclusivity committees, hiring of underrepresented filmmakers on our faculty [and] a better and more diverse selection of clips [to teach concepts like ‘long shots,’ ‘zoom shots,’ ‘crossing the line’].” He adds, “We are also introducing a mandatory class in diversity to be taken by all incoming first semester graduate students.”

Through the UFVA, filmmaker Jen Proctor has been conducting surveys, finding that “the limitations of the canon as shared in film classes are perhaps the most often cited among both faculty and students as a way in which we fail our diverse student bodies, both in film production classes and in film studies classes.” The diversity of the films taught and the diversity of the instructors teaching them are, of course, related. “Instructors who are women, of color and/or LGBT make far more of an effort to be inclusive because we are forced to pay attention to issues of identity, difference and diversity on account of who we are,” contends Mary Celeste Kearney, director of gender studies and associate professor of film, television and theatre at the University of Notre Dame.

While some schools are just now starting to think about diversity, the University of California, Los Angeles is a notable exception. In 1969, Eliseo Taylor, one of the school’s few Black faculty members, initiated the Ethno-Communications Program, working with a coalition of minority students that included Charles Burnett. While the program only lasted until 1973, it’s seen as an origin point for L.A. Rebellion cinema, acknowledging a cohort of Black filmmakers who went through the UCLA program and collaborated on one another’s films. Burnett’s 1978 film Killer of Sheep, which today is the only token African-American film on many intro class syllabuses, was actually completed as part of his UCLA degree and using university equipment. With this legacy in mind, the school continues to prioritize diversity in a spirit of reimagination. Kathleen McHugh, professor and chair of the department of film, television and digital media at UCLA, argues, “The goal is not just to shoehorn in more underrepresented groups — that is, to supplement the canon. It is to rethink the larger field of film and media culture itself.”