Back to selection

Back to selection

No Sell Out

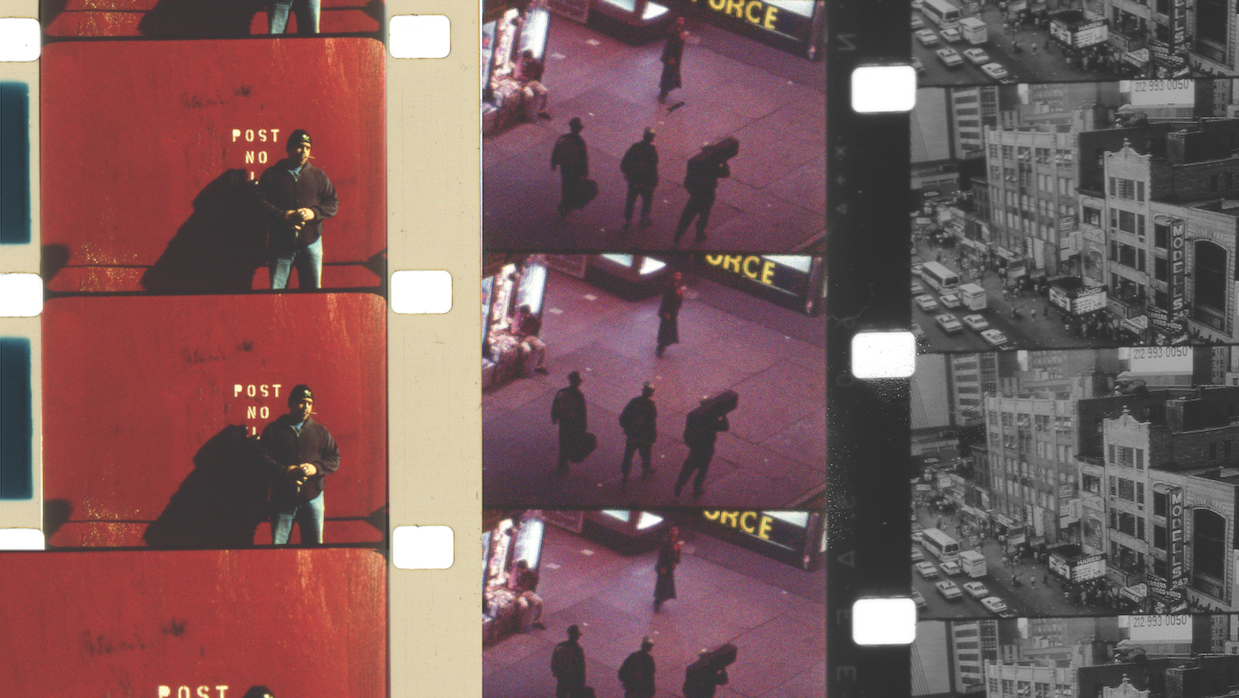

A collage of early '90s 16mm fragments from artist and filmmaker Jem

Cohen's going-on-30-year 42nd St. / Times Square project, Late City Final

A collage of early '90s 16mm fragments from artist and filmmaker Jem

Cohen's going-on-30-year 42nd St. / Times Square project, Late City Final In the infant years of this publication, Ted Hope wrote a piece musing on the death of 1990s off-Hollywood production models, and controversy arose! I was only 12 at the time, but I glean now that there was a sense then — at least in this tiny community of cultural producers and aspirants — that the debate within Hope’s “Indie Film is Dead,” (and then-partner James Schamus’s response “Long Live Indie Film”) mattered. But here we are, making magic together still. This 25-year-old magazine, and the tiny corner of the entertainment industry it covers with a level of detail and specificity and genuine passion you will find nowhere else, lives on.

But, of course, one summer day you looked up and it was 2017, and you had no idea what anyone meant by “independent film” anymore. Almost everyone you knew working in what used to be a coherent, verbally identifiable medium — the pinnacle of which were unique and meaningful works of art that lived on celluloid and displayed in theaters before migrating to “home video” — shot “films” on digital video ported directly to hard drives and wanted to make television serials that you have to own a computer or “smart TV” to watch. What’s more, these “films” only aspire to offer the same things — relatable characters with identifiable arcs and easily readable plot progressions conveyed using unremarkable aesthetics — that regular old TV and most Hollywood cinema have traditionally provided over their own long histories.

You’d seen this moment coming for years, so you weren’t even that shocked to discover that what you used to mean when you’d said “I’m an independent filmmaker” had slipped into the realm of the ephemeral — into dreaded, unshakable meaninglessness. James Murphy once sang “Losing My Edge,” and now you thought, has it happened to me? By 2017, every aspect of American life was like this. Were the best years behind us? Was I born into an era of unspeakable decline for not only the medium but also our politics and environment?

The movies, as always, simply reflected who we were even if we were, more often than not, using them to lie to ourselves. But they had opened up worlds to you. Through them, you had wrestled with all the most difficult aspects of life. They were the way you saw yourself whole, a springboard you used to gain a bird’s-eye view of the treachery and beauty that seemed so commonplace in our sorry and wondrous times.

Were there ever golden years for indie film? If those years had existed, you certainly hadn’t been there for them. The movies themselves were now cheaper than ever to make but harder than ever to get seen. Glut was the problem, not scarcity. Festivals numbered in the thousands, features for them to choose from in the tens of thousands. What was the confused viewer to do? Trust in Netflix because its algorithms will surely provide an answer?

But, really, what was so bad about this state of affairs? Big multinational conglomerates with money to burn and streaming subscribers to please were letting exciting new motion picture storytellers do their thing on a scale that wasn’t so unimaginable when I began covering film festivals for this magazine ten years ago yet still seemed like a quaint and unlikely possibility. The cats I met out at those first fests I covered are doing a variety of things now — not just making features, but engaging in motion picture storytelling across many platforms, be they internet, or virtual reality or celluloid with light passing through it. Why feel sorry for them or for the culture that gets to consume their thoughtful works?

But, you come to understand, such a rose-colored view doesn’t change the fact that you and your successful friends are living in today’s impossible-to-subvert American cultural landscape, in which everything has already been done and where financiers and executives would rather recycle old visions than invest in new ones. Besides, all the motion picture artists you knew had to become entrepreneurs in order to continue as artists and, hell, when had it not been that way?

Oscar Micheaux spent his whole life hustling, and John Cassavetes, too. Who were you to feel above it?

But it still felt wrong. Meaningful artmaking seemed both closer than ever and further away on the agenda for most of the filmmakers I knew; they simply wanted to keep making things for anyone who would pay. “Selling out” was a term whose value had come and gone — or so screamed the chorus of today’s indie film journalists. We knew not who we were anymore, or rather, we knew who we were, and we were something different than what we once could have been, due to forces of commerce that were bigger than all of us and could not be abated.

Nowadays, few young hungry motion picture artists question the wisdom or motives of the middle-aged men, the industry “veterans” in business casual who check their smartphones 200 times a day as they tell you — at some festival panel that cost hungry rubes $120 to attend but that you got to go to for free because you’re in “the business” — that in order to survive amidst the worldwide annual deluge of 50,000 new, instantly available feature films you, an artist who just wants to make meaningful things in a system that will recognize your talent, need to become your own best shill, your own best fundraiser — along with the 15 other jobs that one day in the past might have belonged to someone else.

So the movies weren’t exactly healthy, either, on that summer day in 2017. Despite all the remarkable visions that you had the chance to touch up close, their provenance in worthwhile subject matter and their execution graceful, you doubted that, generations on, anyone would care or notice.

As the heat rose in late July, whether you had central air or not, and the evening news got grimmer and grimmer, none of us were prepared for what was to come. We thought we saw a collapse of this industry in 2007 and this country’s economy in 2008, but — oh, just wait — the real fun is only now beginning! Will anyone watch any of these movies, 100 years on — or even 25 years from now, when New York will allegedly be approaching a sunken, humid, urban answer to Bahrain? Will we have spent our lives reading and watching, writing and making these occasional treasures of late Americana only to watch them burn with everything else? Time will tell. But if we’re lucky enough to be here 25 summers from now, still watching and making and meditating upon movies, I’ll meet you inside the Angelika, where, despite the unbearable noise of the subways passing underneath, I’ll be watching Pitch Perfect 8 — if only just to sit in the AC.