Back to selection

Back to selection

Keeping Print Criticism Alive in the Digital Age

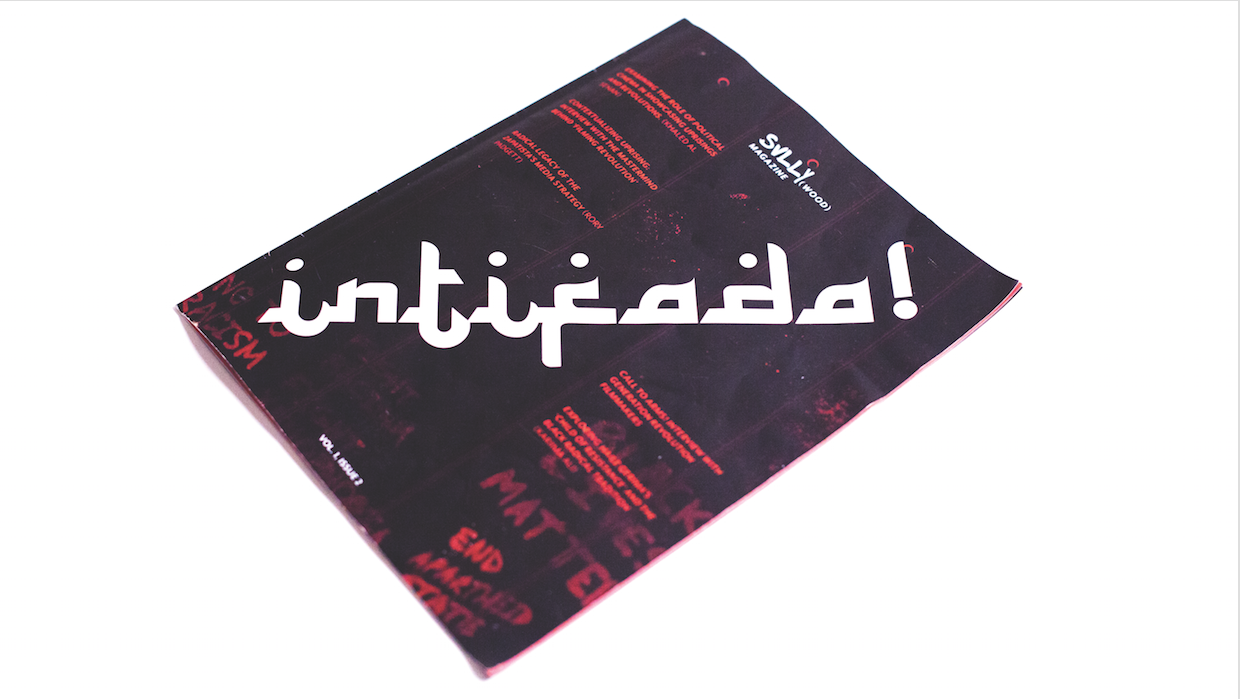

Photo by Caspar Newbolt

Photo by Caspar Newbolt As Filmmaker contemplated its 25th year of print publication, we took note of a younger generation of filmmakers and critics investing their own new energies into the form. One is SVLLY(wood), a “biannual multimedia experimental print and digital magazine, geared toward building a new cinephilia through diverse themes and leftist ideology.” Here, its editor and founder, Rooney Elmi, explains the magazine’s creation.

SVLLY(wood) was created on a whim or, as stated in our inaugural bulletin: “This magazine is the creation of the goals, ideas, ramblings, heartache, desire, and — most supreme — sheer optimism for carving a subversive current in the cinematic status quo.” Totally frustrated by my daytime duties as project acquisition manager at a high-end postproduction studio, I decided to “borrow” some office supplies and outline a manifesto onto some construction paper in the spring of 2016. Despite its inception being born out of creative urgency, the idea of assembling a zine had been on my mind for the better part of a year. After constantly preaching about acknowledging the intersection of art and radical politics in a neoliberal-plagued contemporary film criticism establishment — one that allows cognitive dissonance to flourish while heavily focusing on weekly roundup reviews with no emphasis on in-depth scholarship or emerging marginalized voices — I wanted to create a zine in the vein of the leftist political gazettes whose agenda and aesthetics had inspired me growing up. Weekends spent selling $1 print issues of Socialist Worker around my sports-driven college campus; Emory Douglas’s seminal artwork in The Black Panther, an offshoot of the Party’s revolutionary black nationalist organization; and Dissent’s focus on politics and radical imagination helped evoke the beginning steps of brainstorming what a revolutionary film journal that followed the same template might look like today.

As a black Muslim woman, I have noticed that the lack of representation on screen is equally reflected in criticism. Today’s conversations about diversity are obtuse when mastheads don’t even attempt to reflect the times. A new publication, I thought, could extend the legacy of women-centric film editorials born out of second-wave feminism, which sought to reshape the mainstream and helped usher in a new paradigm for cinephilia. Jump Cut now proudly hosts the archive of Women & Film, referred to as the first-ever feminist film magazine. Founded in southern California in 1972, it gave way to Camera Obscura, whose cofounders had both contributed to W&F. Just two years later, German feminist trailblazer Frauen und Film established itself, and in the shadow of the Riot Grrrl movement, Miranda July began curating the DIY video archive and fanzine collective Joanie 4 Jackie, which recently has been acquired for publishing by Getty Research Institute.

Online, the voices that were once designated at the margins are today pushing the boundaries. From the Toronto-based team at cléo to Another Gaze, DISPATCH, Bitch Flicks, Joan’s Digest, LOLA and newly formed Mai, there seems to be an unofficial renaissance for feminist visual media outlets in the digital realm. The Internet has also opened spaces for Black Girl Nerds and the black women in horror website Graveyard Shift Sisters to survive and thrive amongst the expanding media ecosystem online. But with Melbourne-based zine Filmme Fatales recently going on hiatus after four years and eight issues, the feminist film print scene seemed wide open for the taking.

With all that in mind, it was a no-brainer for me that SVLLY(wood) would run in print: an underground publication that could be shared as an ode to yesteryear while honing a unique new position among its digital peers. As a proud member of Generation Y, I’m hyperaware of our collective coming-of-age journey being consumed and later disregarded online. Over the past decade, we have created a massive digital footprint courtesy of countless hours logged onto LiveJournal, Tumblr, MySpace and community chat rooms, where our burgeoning identities were formed alongside idiosyncratic scholarship, only to have abandoned or deleted them due to privacy or personal growth concerns. Observing — and participating in — this behavior has informed my growing inclination toward maintaining a physical print archive. Even as a political organizer, I’ve noticed there’s a much higher percentage of engagement from protesters to self-educate and return to another event if there’s a signup sheet and on-hand literature. Relying on people to connect through a different dimension than the one you’re sharing is a fallacy.

Yet, if I wished to make a political statement and guarantee a larger audience, establishing an online presence was vital. To adhere to our creed of accessibility, it was necessary to connect the URL to the IRL by having a website, where we’d publish articles online and make all digital issues of the magazine free for our readership. If we possess the magic and might of the internet, it would be foolish and, quite frankly, apolitical to not weaponize it to the best of our ability. So, following our principle of experimentation, we formed a digital playground in addition to our print edition. As of right now, we’ve featured original poetry, graphic design, music playlists, audiovisual essays, handcrafted animated short films and gifs as marketing tools, and hope to add even more as time goes on. We’re curating what Paul Brunick, founding editor of Alt Screen, prophesied in 2012: “I think the film critic of the future will be more like a DJ in a club. Sampling and mixing together reviews that people have written, viral videos and frame-grabs.”

Yet, in this ongoing “pivot to video” media landscape, the urgency to continue print seems more crucial than ever. However, keeping print alive simply for aesthetic reasons is a vacuous idea, especially given the expenses that tag along with physical media production. Nor should print be part of an arbitrary push toward continuing the legacy of vintage models of publishing. There’s a reason why print media is on the wane — again, it’s expensive! As dialogue surrounding the democratization of art rages on, an obligation for nuance in our public and private debates must remain. Discourse over “analog vs. digital” and “print vs. online” is a stale one in an ever-expanding media environment that allows both creative outlets to shine. One of capitalism’s severe consequences is the license for unmitigated competition to thrive even when there is no direct strife to begin with. We as artists, critics and creatives have to end the promotion of the “vs.” agenda when, in reality, allowing for multiple mediums of exhibition symbolizes maturity in an age-old profession.

As film criticism continues to transform, the popular move to multimedia platforms doesn’t have to translate into the annihilation of print journalism. Academic peer-reviewed journal [in]Transition, Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin’s scholarship on MUBI’s Notebook, Nelson Carvajal’s catalog on Indiewire’s Press Play, Kevin Lee’s collection on Fandor’s Keyframe and film critic Charlie Lyne’s feature-length cine-essays (Beyond Clueless, Fear Itself) have helped to push this new wave of audiovisual essays. Along with more interactive avenues like podcasts and video interviews, we can see how cinephilia has been an unsung hero in pushing the envelope toward more creative channels of journalism. With all these different avenues ripe for more exploration, a new age of journalism shines bright in an otherwise pessimistic landscape. Indeed, given the opportunities of this current moment, to reject the encouragements print publishing provides without trying to keep it alive, by any means possible, would be benighted.

You can buy print copies of SVLLY(wood) Magazine, share our PDF, read our submission guidelines, or make a donation at our website, svllywood.com.