Back to selection

Back to selection

Page View: Daniella Shreir on the Debut Issue of Feminist Film Journal Another Gaze

Feminist film journal Another Gaze heads to New York this week for two events surrounding the issue launch of their debut print edition. On Saturday at the Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation there will be a free day of discussions and panels, and, on Thursday at Union Docs a screening of shorts in which women filmmakers reframe onscreen sexual violence. From our own print issue, here’s our interview with editor Daniella Shreir about her decision to add an analog component to her already impressive web publication.

“I didn’t want it to look too essentialist or zine-y,” says London-born writer, editor and designer Daniella Shreir. “I didn’t want it to recall the vagina imagery of the 1970s, ’80s, ’90s zine scene. I admire that scene a lot, but we need to be doing something different.”

Shreir is speaking about her new feminist film journal, Another Gaze, the impressive — and, yes, strikingly designed — debut issue of which has just been mailed to subscribers worldwide. Following the 2016 launch of the Another Gaze website, the journal extends that site’s strong curation — among its web pages are essays on female friendship in the work of Jeanne Moreau and Marguerite Duras, video interviews with directors ranging from Laura Mulvey to Sophie Fiennes and reporting on the recent Kelly Reichardt symposium at the BFI — into the world of print, rethinking as it goes the proper positioning for a feminist film magazine in 2018.

Of her decision to launch a work of physical media in this digital age, Shreir says, “Another Gaze was always going to be online and in print: to reach people who aren’t as engaged with the internet, for archival reasons and to be part of a more academic network. And online is more ‘flitty.’ I don’t think people go to our website to read through a bunch of long articles. I was thinking also about concentration spans in terms of viewing — like streaming vs. going to the cinema. The drifting spectatorship of the small-screen viewer is akin to the online reader, and that’s opposed to the pleasures that come from the forced concentration of being in a cinema and holding a print magazine.”

This premiere issue of Another Gaze consists of five sections that, Shreir says, “guide the reader, in a way.” The first is “First Light,” which includes pieces about pioneering female filmmakers (Alice Guy-Blaché, Germaine Dulac) and an essay by So Mayer challenging the ways in which female filmmakers are permitted to be influential. (Mayer writes, “Female filmmakers — as and when their existence is acknowledged — get written out of being influential and are only admitted as a ‘woman under the influence’ […] We need to invest in what Lucy Bolton calls ‘feminist geneology’ […] which connects women and their work to one another but might also admit that female filmmakers could influence individual male filmmakers — or even film culture more broadly.”)

“Early Viewing” includes the essays “‘Regarding Susan Sontag’ and the Anxiety of Influence” and “Queering the Absence: How I Made My Place in Other People’s Films” and looks at spectatorship. Says Shreir, “How are women in 2018 looking, and how were they looking when they were young women or teenagers? The Sontag essay is especially interesting because it’s about how we look at an impressive woman on screen whom we admire but at the same time who makes us extremely anxious, which is a massive concern for my generation. I want young filmmakers to watch all these women’s work, but it can create anxiety — like, ‘What am I doing!’” The third section is “Women Looking at Other Women” — essays on how filmmakers like Bette Gordon, Chantal Akerman, Kathleen Collins and Moyra Davey represent their female subjects.

The fourth section, “Sound and Visions,” offers, says Shreir, “a mixture of otherness on screen”: an article about trans women in the work of Rosa von Praunheim, an essay on cinematic representations of rape, and Fiona Handyside’s piece on the theme of female friendship in Éric Rohmer’s work as considered by way of his collaboration with Sophie Maintigneux. The young Maintigneux, who shot The Green Ray and Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle, was the first female cinematographer Rohmer had worked with, and her contributions to the thematic content of his work is discussed through her choice of lenses, shooting format and camera positioning.

The final section, “Looking Around,” is what Shreir dubs Another Gaze’s year in review, albeit one adjusted for the more extended rhythms of print. “Our reviews aren’t always timely,” she says. “We don’t respond quickly to a film because there’s a need to be not reactive, for a more careful approximation of what a film can be instead of a pigeonholing of it. We want films by women to last longer in the public mindset, and not just for the amount of time that mainstream websites are trying to appear ‘woke.’ Film outlets want to hire the person who shouts the loudest and writes the quickest; all of online film culture is based around this idea of speed, turnover, the production line — we’re trying to think differently.”

The 25-year-old Shreir’s inhabiting of the dual roles of editor and designer partially explains the debut issue’s robust 180 pages. “I was in a struggle with myself,” she admits. “As an editor, I wanted to fit in as much content as possible and as a graphic designer I wanted to give each article as much space as it needed.”

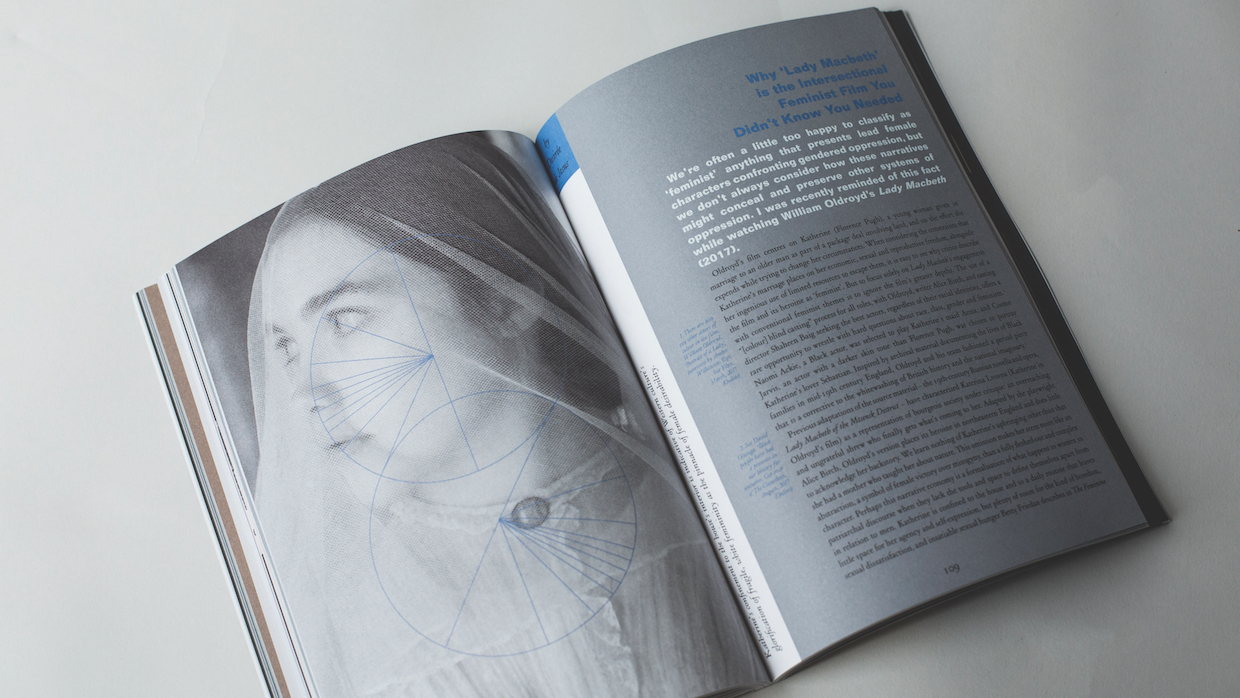

As for the design itself, the concept of the spine — the kind of vertical stripe that instantly distinguishes a Criterion DVD or a BFI Modern Classic monograph — is integrated throughout the edition as a kind of visual motif, ping-ponging across page spreads and containing bylines and pull-quotes. Pages are both single and double column, and there are full-page director portraits as well as bursts of geometric abstraction. A trapezoidal shadow appears here and there, while the nested circles on the cover are meant to “represent the lens,” says Shreir, even as the design strategy might suggest “the kind of écriture féminine–type bullshit which I admire and appreciate as theory but don’t subscribe to.” Indeed, Another Gaze’s design style looks away from a kind of late ’90s/early aughts postmodernist lineage (Neville Brody, Paula Scher, David Carson) to, perhaps, the original influences of these designers — Russian constructivism and the avant-garde of the early 20th century. “It’s October-esque,” says Shreir. “I wanted it to look like a literary journal — a bit ahistoric — while being accessible.”

The magazine’s modest price tag — £8.50, with options for readers to pay what they want — is also part of the mission statement. (Visit anothergaze.com for more info.) “The foundational premise of Another Gaze is to bring this type of writing out from behind the paywall as well as the academic subscription,” says Shreir.

In terms of its economics, Another Gaze crowd-funded the creation of its website, secured a deal with Amazon Prime for its video director interviews, creates custom supplements for home video distributors (Another Gaze content can be found on the U.K. DVD release of Hope Dickson Leach’s The Leveling, for example) and receives grants to send its writers around the world to interview directors. The first issue is already nearly sold out, and a second printing is planned.