Back to selection

Back to selection

A Matter of Trust: Independent Film and the Blockchain

Trust Machine: The Story of Blockchain, courtesy of SingularDTV and Futurism Studios

Trust Machine: The Story of Blockchain, courtesy of SingularDTV and Futurism Studios In his novel Enduring Love, Ian McEwan constructs a striking metaphor of the tension between individualism and cohesion that lies at the core of modern society: Five strangers rush to save a child stuck in the passenger basket of a hot air balloon being uplifted by the wind. As the balloon soars, the helpers find themselves in midair, hanging from its ropes. Their cumulative weight keeps the balloon hovering over the ground, but one person letting go would break this fragile pact and put the others in greater danger.

This scene, which resembles a social psychology experiment, asks the question: How do we establish a system of trust that overcomes our individualistic instincts and promotes collective progress? (Spoiler: In the novel the strangers drop one by one, dooming the final rescuer.)

Examples of common unifying forces currently regulating our interactions would be a central authority like a government or the global financial system. For many, blockchain offers an alternative solution.

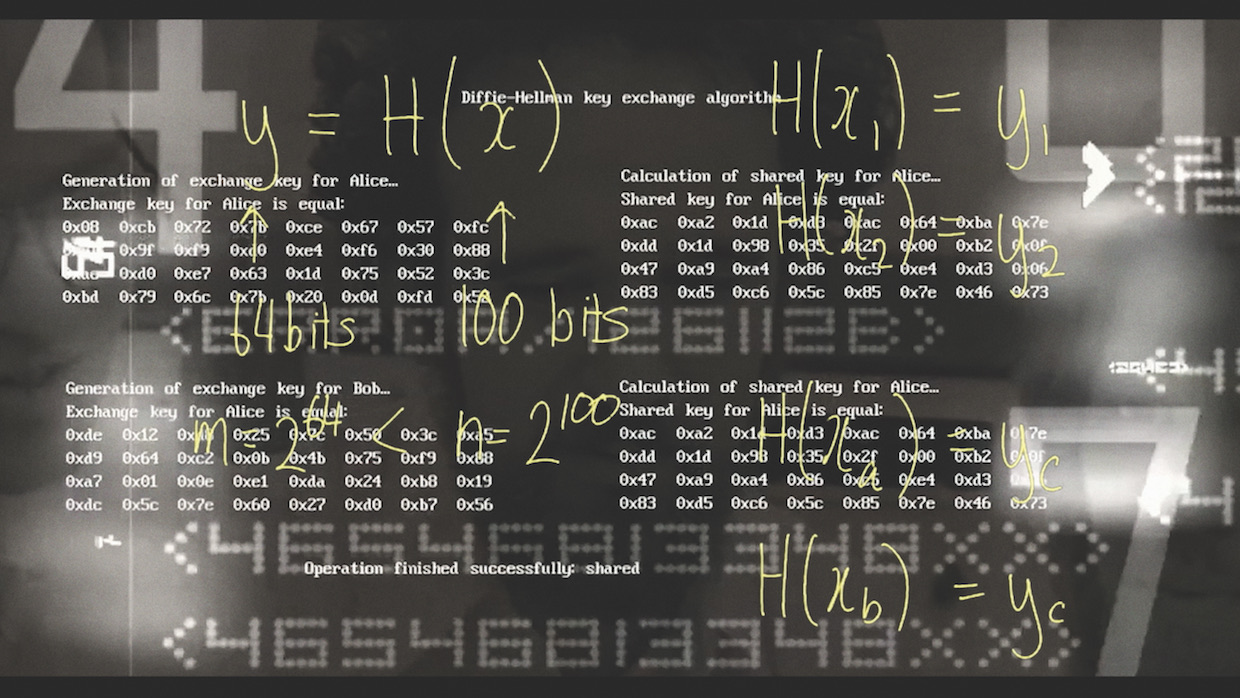

Blockchain technology was created to enable Bitcoin transactions. Because digital information can easily be reproduced, its aim was to prevent fraud without requiring a third party like a bank to keep watch. In this new participatory system, the record of all transactions—the blockchain—is housed on all the computers in the network in a decentralized manner, much like BitTorrent.

The two entities—blockchain and cryptocurrency—should not be conflated. The chain can record more types of information than cryptocurrency transactions, which is why it is described as a “distributed database” or “decentralized ledger.” The responsibility of validating new blocks of information is spread across the members of the network through different types of consensus protocols. The most common one, Proof of Work, sees members use their computational power to solve a mathematical puzzle comparable to finding the numerical sequence that opens a lock. This process is called “mining,” and miners who find the right combination are rewarded in different ways, such as with cryptocurrency or transaction fees. The peculiarity of this system is that the records cannot be erased as long as there exists at least one computer maintaining a copy of the chain, so no one entity has the power to control the information it contains. Additionally, because each block contains a record of the transaction before and after it, any attempt to tamper with it would be singled out and break the chain.

As McEwan’s example illustrates, we are good when it is easy to be good. Blockchain is seen as a way to replace trust with technology, facilitating cohesion between independent, unknown parties by aligning the collective’s best interest with the individual’s best interest.

While blockchain can simply be described as a giant spreadsheet holding immutable records, its structure, which evenly distributes power, and its emergence right after the 2008 financial crisis as an alternative to traditional banking systems, inevitably invests the technology with a higher meaning. When discussing blockchain, you will hear words like “trust,” “transparency” and “accuracy.” These words do not just apply to a system that is pure mathematics but also express values that we feel are missing in our daily interactions, be they personal or professional, especially when the additional layer of the internet is involved.

The film industry, with its combination of art and business, has always carried idiosyncrasies and inefficiencies. Yet, in more recent times, the increase in product and speed of transmission owing to the digital revolution seems to be reflected in the rise of the number of parties involved in a film’s lifespan. This has exacerbated opaqueness, giving many creators the feeling of losing track of their projects and of being cut off from audiences and revenues. In this context, a system highlighting truth and transparency is an attractive proposition.

Alex Winter (Downloaded, Deep Web), director of the forthcoming documentary Trust Machine: The Story of Blockchain, observes, “Like many industries at the moment, the film business is in transition; the means of distribution and consumption are shifting to digital, but there isn’t a working system in place. Artists aren’t being fairly compensated in the new paradigm, and it’s unclear if the current streaming models are sustainable.”

With this in mind, several companies are, they say, determined to harness blockchain technology to reduce the current system’s inefficiencies and facilitate film financing, production, distribution and marketing, all with an eye to shifting the balance of power back to the creator. The platforms they are building don’t take any rights from the filmmakers and focus on providing them with truthful, up-to-date information on their title’s revenue and royalty flow.

Cinemarket, Cinezen, SingularDTV and Treeti all approach the problem from different angles, reflecting their founders’ specific backgrounds. In all cases, they are spearheaded by passionate filmmakers, often veterans of the industry, who were led to blockchain by their vision for a solution, not vice versa.

Cinezen, founded in September 2017 and based in Sweden, launched the alpha version of its product at Cannes 2018. Its founder, distributor Sam Klebanov, imagined a video-on-demand platform reminiscent of the world of independently run video stores. The Cinezen portal will consist of individual “stores” curated by third parties, which viewers can select according to their tastes. Because the goal is to de-monopolize content, Cinezen will have no say in how the titles are being displayed or promoted. “A store is a showroom,” says Klebanov. “Anybody can run their own store and attract their own audience using their own communication channels.” He describes the value of a more granular approach to curation and promotion than, say, a Netflix: “If you have a film for a certain subculture, then it can be in a very prominent position in the store focusing on that audience. Different films can be in different stores for different reasons, and we can build the analytics to connect the rights holders to the most suitable stores.” Storeowners rent the space on the platform for a low fee, while Cinezen, storeowners and rights holders are paid directly and simultaneously by the end user according to their respective shares. This is done through smart contracts—code incorporating certain deal terms that, when met, trigger an automatic action (e.g. a payment).

While still busy with the platform’s development (the beta version launched in August 2018), Klebanov is building a library of content, talking to various players in the industry from filmmakers to sales agents. Deals have been announced with likes of Celluloid Dreams in France, Celsius Entertainment in the UK and NonStop Entertainment in Sweden.

One challenge faced by the company is to persuade rights holders to work with it without a minimum guarantee: “Why pay an MG when we are only providing the technology that will connect the rights holder with every single user anywhere in the world?” says Klebanov. “What we can offer instead is total transparency and accountability, which are provided not only by us but by the blockchain technology itself.” Even when the party offering a product on the platform is a traditional distributor, Klebanov believes that the creator will still benefit because, by decreasing the administrative burden and making up-to-date information easily accessible, blockchain will encourage fairer, more transparent relations between all the members of the value chain. He considers traditional distributors and sales agents still essential to the ecosystem: “Curation is key. Often in the context of blockchain, people talk about removing the intermediary, [but] the reality is that there is no real demand in the film industry to take away the middle man because then the filmmakers would be left alone with the audience, and the audience would be left with an unstructured pile of films.”

Kim Jackson, founder and president of entertainment at SingularDTV, as well as a longtime indie producer (Blue Caprice, Jack Goes Home), echoes the sentiment. “It’s not about putting anybody out of business,” she says. “It’s about the inefficiencies related to intermediaries being alleviated from the equation, and so we are building tools and applications that allow for rights royalty management to flow in a way that allows for the company and the individual filmmaker to reap the benefits directly and, more important, have that data and direct connection with their audience, which is another place where we’re being cut off.”

SingularDTV produces original content, such as Winter’s Trust Machine, acts as a traditional distributor, and is building a platform for rights management, project funding and peer-to-peer distribution. At SXSW, it acquired Eddie Alcazar’s Perfect, which they will distribute on traditional platforms as well as their own. This dual presence in new and existing markets, Jackson believes, differentiates SingularDTV and will allow all the different stakeholders to appreciate the benefits of their technology.

The SingularDTV platform is about to launch in its alpha version, with a beta version planned for the end of the year. The company has developed an application called Tokit to upload a film to the blockchain. Tokit essentially embeds the intellectual property in a token (an asset tradable on the blockchain), which then allows the owner to trace all transactions and viewing data relative to the title.

But the blockchain studio has a more ambitious vision to help artists finance their projects through the platform. The concept—a form of crowd funding—is inspired by David Bowie, who in 1997 created Bowie bonds, securities representing future royalties for his existing catalogue, which were sold on Wall Street. Similarly, filmmakers are able to “tokenize” their own or their film’s value through financial analysis tools and sell shares to finance their projects. The purchaser is left with a tradable asset, the value of which would depend on the market.

SingularDTV, which is headquartered in Switzerland, was able to experiment with this concept with electronic dance musician and DJ Gramatik, who raised the equivalent of $9 million by “tokenizing” himself. However, such practices are currently illegal in the United States, a reflection of regulators’ skepticism toward cryptocurrency, likely a result of its previous negative association with online black market Silk Road and of fraudulent activities surrounding Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs).

Scalability, the system’s capability to handle a growing number of transactions, is another issue facing blockchain developers. The “mining” verification system is time consuming, therefore slow. Jackson is open about these technical hurdles: “It’s definitely a concern of ours, scalability, but it’s something that a lot of very smart people are working on solving. It’s like the dial-up days. Can you imagine in those days being able to stream a movie?” Jackson continues, “The other part of the puzzle is just more users participating in the network. If we had more people verifying these transactions, we would have a much more robust network, and so a lower entry barrier is key. It’s just about general blockchain education, and unfortunately a lot of the press out there has been sensationalizing the ICO scandals, which is not the point of blockchain.”

But while the concept of “trust” underlies many blockchain adherents’ arguments for the technology, Florian Glatz, co-founder of Berlin-based Cinemarket, believes that another major obstacle to the adoption of blockchain is, ironically, a trust issue. “The ultimate thing that prevents blockchain today is the mindset,” he says. “It’s trust-less. It’s only mathematics, and most people are not good at mathematics. They ultimately have to trust people.” He argues that many stakeholders in the film ecosystem have arranged it in a way that works primarily for them, while those who are not successful because of structural reasons lack a voice. He says Cinemarket aims to give those people a voice, while incentivizing existing payers to adopt new rules of governance and distribution.

Supporting new talent is at the core of Cinemarket’s ethos. The company emerged a few years ago from the conversations of film students in Berlin. Tired of seeing their films disappear into the archives of their universities, they were looking for a means to finance them and distribute them internationally. Their vision gradually attracted film professionals like New York–based director of content Jordan Mattos, and Glatz, who is also a lawyer and software developer. Cinemarket’s first step was to focus on the distribution problem. “Until today,” Glatz continues, “film festivals have been the only place where distributors can discover movies by young and upcoming filmmakers, and after one or two festivals, the window of opportunity for a film to be sold is closed. Cinemarket makes that window persist 24/7.” It does so by providing a rights-trading B2B platform, where distributors and rights holders can meet and negotiate license agreements. First, the seller submits the content to the curatorial team. Once it has been approved, negotiations between potential buyer and seller ensue, similar to how eBay works. The company collects revenue from a percentage on the transaction fee and from the seller’s monthly subscription fee. Blockchain is combined with legal tech to not only follow the revenue stream but to also facilitate the licensing process. Glatz explains, “We have a tool that lets the rights holders specify through a simple interface the important parameters relative to their license. This already improves the situation for small filmmakers, who would previously be forced to accept whichever terms were being proposed by the stronger counterparty.”

Cinemarket’s ultimate, ambitious goal is to implement a scheme that redistributes the value generated by the film industry fairly. For this reason, they too are developing a system to tokenize a film into a stock-like asset on the blockchain, which is planned for next year. Within this ecosystem, the role of curation, especially of film festivals, is reimagined: “Curation already has its place today, but it’s massively underexploited and disconnected. Film festivals naturally have an incentive to curate films because it’s how they sell tickets,” Glatz says. “What they do is really important work, but after the festival is over, most of the films will never be seen again. In our model, curation is an act of investment, and festivals will be long-term investors in the future success of the movies they curate.”

Curation is also a fundamental in the vision of new company Treeti, the brainchild of former Starz Media marketing executive Amorette Jones and entrepreneur Matej Boda, founder of blockchain company DECENT. Treeti describes itself as a socially activated viewing platform, and it strongly reflects Jones’ early involvement in the type of grassroots, field-level marketing that incites buzz for a film through word of mouth. With the advent of the Internet, Jones was able to apply these low-tech skills to viral Internet campaigns, like the one she helped create for The Blair Witch Project while executive vice president for worldwide marketing at Artisan Entertainment. Treeti aims to use blockchain technology to exploit word of mouth in a strategic, organized manner, while staying grounded in the human element. Thomas Lakeman, SVP of customer experience, says, “What Amorette’s amazing experiences show is that human connections are major drivers of how we make decisions about what we’re going to watch.”

On the Treeti platform, the ecosystem is populated by filmmakers offering their content, “persuaders” promoting it, and viewers. All of them are incentivized to make connections and are able to communicate with one another through an internal chat system. “We say ’persuader’ and not ’influencer,’” Lakeman explains, “because influencer refers to someone who has a lot of followers but is not measured on his or her power to convert people. Persuaders, on the other hand, are people who are knowledgeable and passionate about a movie and are incentivized by the system to being really good at persuading people to watch it. This takes you, as a viewer, into a space where you are being exposed to new discoveries, which can in turn increase the diversity of the creative voices you will find in our library.” Filmmakers can find persuaders enthusiastic about their film, ask their support to promote it, and reward them, for example, with exclusive content that will help the persuaders expand their networks.

Another feature helping filmmakers to monetize their product is the ability to sell items from the films, like costumes and props, directly to the viewer. Lakeman is adamant that additive experiences like chatting with the film director or making a purchase are always optional, voluntary, and secondary to the content. In fact, Jones says that the content devaluation she perceived on other platforms strongly motivated her to start the company: “These aggregators are not interested in the content. They are buying it in order to take data from consumers and build their model, and then they are not sharing it with you. They have successfully devalued my industry, so I take it personally.”

Blockchain technology is used to verify users and to track data in real time. Besides taking a fee on the rental of the content and sales of ancillary items, Treeti’s other big value proposition is providing its marketing expertise to build a strategy that can quickly react to real-time data about the film and zero in on the geographical areas where it is most promising. Jones describes the novelty of this approach: “Studios and independent companies currently define their marketing strategy on historical data and per-screen averages that have no contextual relevance. Ultimately, what you end up with is the same market list every single time. In-the-moment, contextual data can tell you what’s going on in the market place and gives you the ability to empower a network of influencers to promote your picture in the market place that matters.”

Treeti recently appointed Borderline Media founder and independent producer Jennifer MacArthur (Whose Streets?) as its senior vice president of global marketing and strategic partnerships. The company has also partnered with IFP, Filmmaker’s publisher, in the IFP Expanded initiative, which will provide marketing and distribution support to six projects.

The alpha version of the Treeti platform will launch in September 2018 and run through the end of the year, while the beta launch is expected in early 2019.

You may have noticed over the course of this article that blockchain technology is not easy to describe in a sentence or two, that its contours are fuzzy, and that it often executes tasks that can be completed through current technology and distribution platforms. Yet, more efficient solutions, such as having the certainty of getting paid or making small payments more cost effective, may be more revolutionary than is immediately apparent.

All these companies are founded on the principle that technology should unify and not separate people, yet we should not view blockchain as the Holy Grail that will solve all the industry’s problems. Its potential to reshape the current system and cause a structural shift is dependent on how the film community at large—and the world beyond it—will embrace and harness it. Several corporations, for example, are building permissioned, private blockchains to maintain their authority while exploiting the technology. But its evolution is not an inevitable process to be viewed from the sidelines. The manner in which we choose to overcome the hurdles standing in the way of mass adoption, be they regulatory, technical, or psychological, will determine its future. Blockchain will be, to a certain extent, what we will make of it. If the development of the Internet has disappointed us, this is all the more reason to educate ourselves as filmmakers about how to participate in shaping this new technology. Winter concludes, “Blockchain is an evolutionary technology, and it’s also a transitional one. It’s not certain where it will settle or how much it will change, but one thing is certain, there will be a lot more disruption before we arrive at a landing point.”

This article was originally published in Filmmaker‘s Fall, 2018 print edition.