Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Film Brings Audiences Both The Joys And Pains Of Our Political System Via High School”: Alexandra Stergiou and Lexi Henigman On Their DOC NYC-Premiering The Candidates

The Candidates

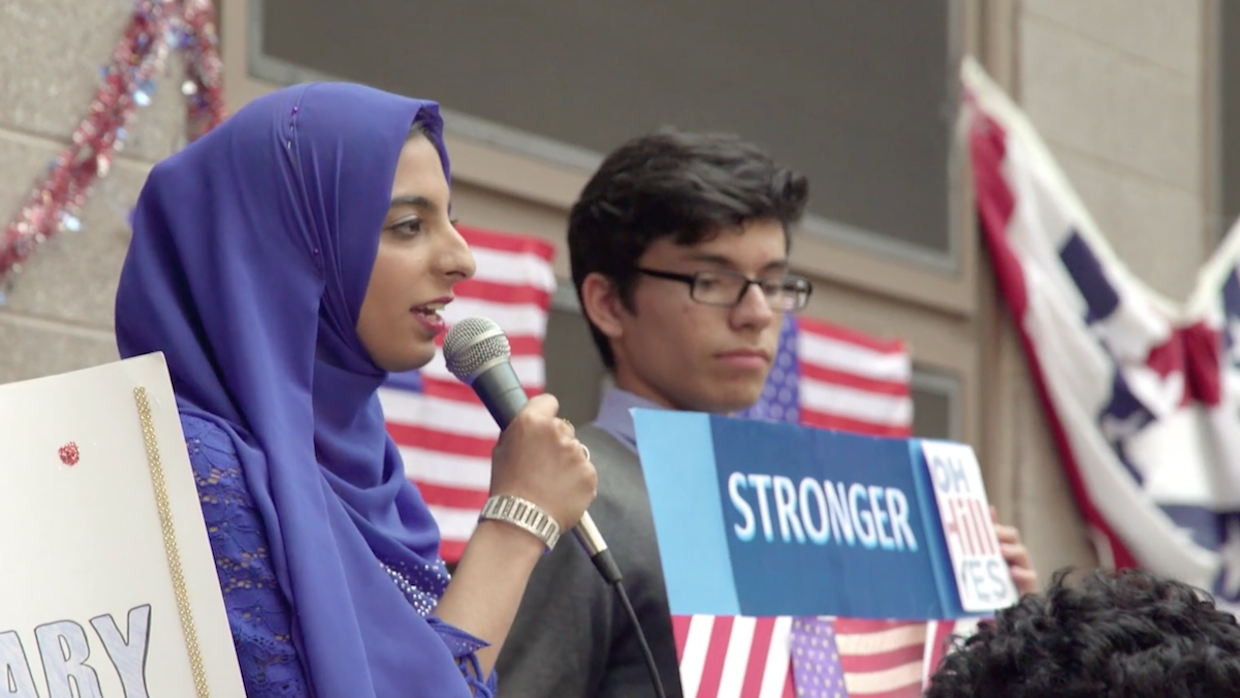

The Candidates If you spent the 2016 election season trying to wrap your head around the surreal circus that passed for political campaigning, just imagine actually participating in it while studying for exams. Such was the situation for the students of Townsend Harris High School in Queens, which since 1996 has included in its curriculum an as-close-to-real-life-as-possible Election Simulation. Fortunately, filmmakers Alexandra Stergiou and Lexi Henigman were there to capture it all. On one side is Russian-American Daniel, aka Trump, trying to focus on making America great again instead of grabbing women by the pussy. On the other, there’s Pakistani-American Misbah, aka Hillary, wooing votes with pizza and halal while coolly parrying xenophobic attacks (and all while wearing the hijab). And of course, there are stand-ins for Gary Johnson, Jill Stein, Bill, Melania, the media, the campaign operatives and all the rest of the sordid “swamp.”

Filmmaker caught up with the co-directors to get the scoop on their fly-on-the-wall look at civic (mis?)education prior to the film’s November 10th premiere at DOC NYC.

Filmmaker: I can’t believe this mock presidential election has been going on at a high school in Queens for over two decades and I’d never even heard about it. It seems like perfect documentary material. How did you first encounter this such-a-New-York story?

Stergiou: It is such a New York story! And more specifically, a Queens story. I’m from Queens, so a big thing for me was that The Candidates show my hometown. Queens is a beautiful place. It’s a vibrant, diverse and, in my opinion, underrepresented slice of the city that I’m sure audiences will appreciate.

I grew up with kids like Misbah and Daniel, and want to give kids like them a voice. As far as the Election Simulation goes, I know it intimately because I went to Townsend Harris and actually participated in the Election Simulation in 2005 when I was a senior. I was the media coordinator for a mayoral campaign, and my job was to create the commercials for the campaign that aired on the school-wide TV network. I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker then, so I was always thinking of excuses to make videos. It was a perfect role for me in that sense.

I wasn’t expecting for the Election Simulation to have the impact that it did. It really opened my eyes to the larger world and got me engaged in politics at a crucial age. Civic education is incredibly important but has become a side note. It wasn’t always that way. Until the 1960s, it was common for American high school students to have three separate courses in civics and government by the time they graduated. We’re hoping the film can get people excited about civics in the classroom once again.

Filmmaker: The number of characters you could have chosen to focus on seems overwhelming. In addition to the students playing the candidates — not just Hillary and Trump, but also Jill Stein and Gary Johnson — there are also the periphery characters, from Bill to Melania, to the media reporters and campaign managers. Did you choose to mostly follow “Trump” and “Hillary” since they were the real life frontrunners, or because a Russian-American and a Pakistani-American, respectively, inhabited those roles? (I’m sure I would have been equally riveted had you decided to trail the kid playing Gary Johnson, who seemed more knowledgeable about Johnson’s policies than Johnson.)

Stergiou and Henigman: You hit the nail on the head. Due to the sheer size of the student body in which we were embedding ourselves, we really had to be focused and create self-imposed obstructions in our filmmaking in order to make a film that audiences would want to watch or make sense of at all. Otherwise there would be no arc and our coverage would have been all over the place. There are over 1000 students in the school, so theoretically there are over 1000 storylines we could have followed. We went in knowing that this would be an ensemble film to some extent. We also knew going in that getting to know all of the secondary characters — from the spouses and third party candidates to the campaign staff and media teams — was very important to us. Both for the richness they bring to the film, and also to show how elaborate this simulation really is.

The way the Election Simulation works is that it happens every fall at Townsend Harris. That means whatever election is happening in the city, state, or nation is simulated in the school in real time. If someone is not running for office at that very moment, they do not have a role in the Election Simulation. If a candidate drops out in the real world, they drop out in the school’s world as well, and so on and so forth.

We were determined to make a verité documentary. We tried to act like flies on the wall and not sway the events one way or another, including the selection of the students playing candidates. Thus, we were incredibly lucky to have Misbah and Daniel acting as Hillary and Donald. They are incredibly thoughtful and dynamic, not to mention strong in every sense of the word. To say the least, they had big shoes to fill. They had to grapple with real world counterparts who were the frontrunners of a dramatic and challenging election, and they played their roles admirably. We wanted our admiration for them to come across in the film, too. The fact that they are both from new immigrant families gives a fresh perspective. But it’s also just an accurate representation of both the student body and Queens, which prides itself on being the most diverse borough in New York, and one of the most diverse counties in the entire nation.

Filmmaker: Can you talk a bit about the production itself? I know Maxim Pozdorovkin has signed on as EP, but I’m not sure how you initially got financing. Was this a crowd-funded project?

Stergiou and Henigman: This film is purely independent. Throughout the process, we relied heavily on our amazing network of friends, who are gifted film professionals. The majority of the crew worked on donated time and the promise of deferred payment should the film make any profit, which everyone knew was not guaranteed. Maxim signed on in the very beginning, as did Joe Bender, the film’s director of photography and Maxim’s creative partner in their production company. They believed in us and the film, and for that we are so incredibly grateful. It’s a great example of seasoned filmmakers championing up-and-coming female directors with a story that’s worth telling.

As far as production goes, it was an intense period of several months. We kept the crew small, the overhead low, and used our savings to cover costs like transportation, meals, insurance, etc. This isn’t a story that drags on for years; it’s about a specific place during a very specific time. Knowing ahead of time that the very nature of our subject matter obstructed our production period, everyone in the key crew saved up, bit the bullet and stuck it out. After that the two of us edited the film over the course of two years between day jobs. It was during post-production that a small amount of actual funding came from individual investors who trust us and believe in our vision. This funding helped us finish the film just in time for DOC NYC. We think the term “labor of love” applies here.

Filmmaker: I’m also wondering about any limits the Townsend Harris High School administration might have placed on production. Were there specific rules you had to follow – or even try to push back against?

Stergiou and Henigman: The school was incredibly supportive of the production, and placed a lot of trust in us as filmmakers. It definitely helped that Alexandra is an alum. The administration supported our vision of making a verité film that takes place almost exclusively inside a high school. Schools are microcosms of society. There is so much to learn from what goes down in the halls. There is also a lot of responsibility. From the beginning, we strove to be objective and never came at it with an agenda. It’s our duty to our subjects — students who are playing a part and exploring their political values. They allowed us to capture it, and that’s a great honor for us as filmmakers. The film brings audiences both the joys and pains of our political system via high school. High school is a time for most people when your worldview begins to shift away from your home life, and outwards towards the larger world.

Filmmaker: The unforeseen ethical dilemmas posed by the 2016 election put the teachers in a tough spot. On the one hand, this is supposed to be an election simulation, adhering to real life. But on the other hand high school students should not have to be addressing a “pussy tape,” in the case of Daniel, aka Trump, or xenophobic hate speech, in the case of Misbah, aka Hillary. We see glimpses of the adults’ reactions, like when the advisor tells Daniel to try to stay away from the “pussy tape” topic. (Though Daniel complains that he’s trying, but the media won’t let him.) Were you privy to any discussions or debates amongst the adults about how to handle what was devolving into an R-rated campaign? I can see parents taking issue with, say, their kid playing a character being accused of rape (in the case of Bill).

Stergiou and Henigman: There was a lot of debate amongst the faculty even before the election started about how real to let the Election Simulation get. It was surely going to be a divisive campaign, and there were definite concerns about mirroring this in a high school. Since 1996, the Election Simulation at Townsend Harris has prided itself on being as authentic and true to reality as possible, which definitely put everyone in a tough spot, especially when the Billy Bush tape emerged. Although faculty tried to sway the students from this topic, it was never banned entirely since this was a major part of actual discussion surrounding the election.

The simulation holds a mirror up to a series of events we all collectively experienced as citizens. It’s like what’s happening in the real world is clay, the students are the kiln and the results that you see onscreen is an urn that comes out of the fire. And there is a lot to learn from what these students create. The film is just as much about our relationship to historical events as it is about the events themselves. Our understanding of why things happen shifts as our distance increases — and it can only increase. Our film allows our audience to experience this parallax.