Back to selection

Back to selection

Searching for an Independent Distribution Strategy Amidst Pandemics and Streaming Wars

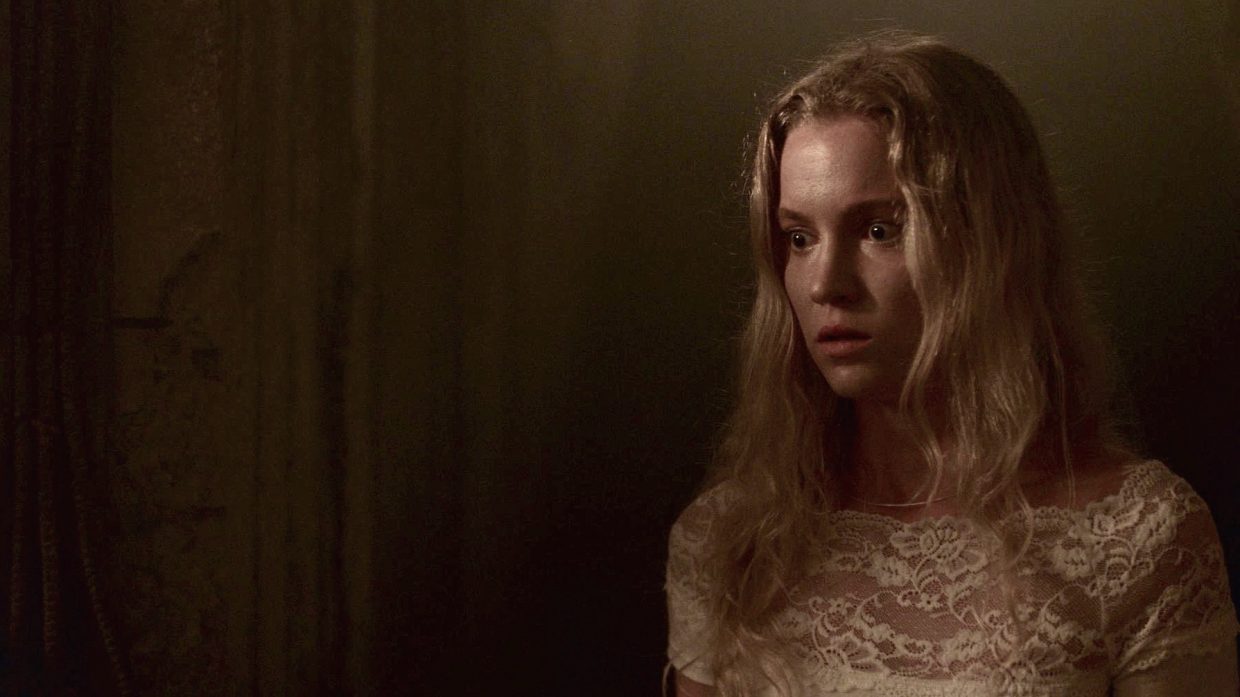

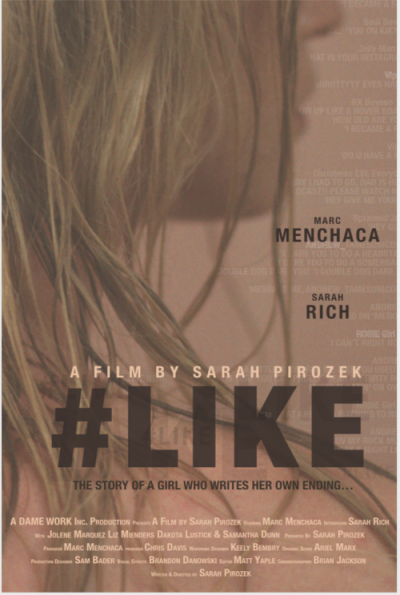

Sarah Rich in #LIKE

Sarah Rich in #LIKE I made a microbudget movie called #LIKE. Amazingly it is wrapped, posted and on the festival circuit, and it has been receiving glowing reviews like this: “Writer/director Sarah Pirozek’s teenage noir #Like pulses with the energy of a ’70s thriller.”

Discouraged by stats on Hollywood hiring and women directors — a 2015 DGA report reported that 84% of first-time scripted TV directors were white men — and inspired by the work of independent female filmmakers like Marielle Heller, Laurie Weltz and Anja Marquardt, I decided to stop waiting for permission to make my first feature. Instead of making a short-film calling card I would write and produce my narrative feature directorial debut, a noir feminist thriller — issued-based and with a story I cared about and a nuanced female lead. In writing the lead character of my film, #LIKE, I was inspired by films like Audrie and Daisy, Roll Red Roll and the heartbreaking real lives of girls whose stories foreshadowed the #metoo movement. Then I met actor Marc Menchaca (The Outsider, Ozark, The Sinner) through a director friend, Scott McGehee, and he became my inspiration for the male lead. (They say not to write with an actor in mind, but this mental casting helped push my writing forward.) The script, a cautionary tale with many twists, echoes true stories of internet predators and a teen who flames out — except it’s not a boy with a gun but a girl with a Percocet. The script opens as rural teen Rosie, mourning the first anniversary of her younger sister’s death, discovers the mysterious man who sexploited and bullied her sister to commit suicide is back online and trolling for new victims. After the authorities refuse to get involved she finds a darker side she never knew she had… as she takes justice into her own hands.

To “make a movie” is a huge undertaking, but then comes distribution, and a micro-budget film is even more of a “lift” than others. The smaller the budget, the less support and the fewer the production partners. A microbudget film usually has no attached talent agencies or sales teams, and any festival connection is usually up to the director. And now, of course, there’s COVID-19, which has altered the festival and acquisitions landscape a film like mine depends on to attract the attention needed for potential sales. In order to think productively about my film and it’s release, I decided to do some research into the so-called “golden days” of recent American independent film distribution. Here is what I learned.

I had a strong story but we — even microbudget filmmakers — are told to get our distribution plan in place before shooting, so I explored the various labs (Sundance, IFP, Tribeca) that promise to help with that plan. They do indeed help some filmmakers, but their focus is on the tightly-knit world of folks already on the radar of the “deciders” that act as a kind of feeder system. This exploration proved to be a blind alley for me — spaces were limited, and my production clock was ticking. (I had already pushed my schedule by 12 months when I lost my lead actress, recasting newcomer Sarah Rich.)

But what did help me enormously as I headed into production and then post were the friends I had made coming up in the business. These included old pal and casting director Mellicent Dyane, who cast my hip-hop music videos. I was grateful when she helped me fill out the supporting players. I wrote for locations I could access for free, and we shot 23 days. The film looks great, performances are fantastic, and we finished it with the support of post production connections: The Edit Center, editor Matt Yaple, composer Ariel Marx and Freefolk Editorial, among others.

But when I started submitting to festivals, I found that the festival world is part of that aforementioned feeder system too. Without sales agents or industry relationships, I didn’t have help in lobbying top-tier festivals like Sundance, SXSW, TIFF and Tribeca. And although my cast are phenomenal they aren’t names. And this is in addition to the glut of quality films submitted to festivals due to the digital filmmaking revolution. (Last year about 4,000 features were submitted to Sundance and about 120 accepted.)

Luckily #LIKE did get accepted into some great smaller festivals like Woodstock and Cinequest, where I decided to have the West Coast premiere. I had the East Coast premiere at The Brooklyn Film Festival. But I didn’t apply to every festival out there, and I didn’t accept all the invitations I received because I was given the good advice not to overexpose the film on the festival circuit. #LIKE was also was selected for The Director’s Finders Series’ at the DGA, where I had my L.A. screening — predominantly industry. The problem I discovered with the smaller festivals is that they are not really “markets” — they work more as film fan/critical festivals. After the first couple of festivals even getting reviewed was a struggle, so I hired a PR firm for the New York screenings, and the film did receive some fantastic pre-release festival reviews, after which indie sales agents as well as smaller distributors, such as Breaking Glass Pictures, reached out and wanted the film. But none of the streamers, nor the more established distributors, were coming for a small-time filmmaker like me. As I explored the sales agents’s offers I found many were asking for a substantial payment upfront just to shop the film

Meanwhile the smaller distributors who approached me seemed to have little marketplace clout, and they weren’t offering a minimum guarantee. They also had high expense caps, meaning that I’d probably see little to no profit. And they wanted all rights, a very long term, plus a high share of the revenue split after marketing costs and distribution fees. A filmmaker friend told me that some of these companies just want to refresh their rosters and don’t do a lot once they actually sign your film. In addition some of these companies had the sort of horror slates where my quirky feminist film, although a thriller, wouldn’t sit well alongside often misogynistic slasher pics…I scratched my head.

April Wright, director of the poignantly timely, Going Attractions: The Definitive Story of the Movie Palace, shared her two cents with me: “The traditional sequence doesn’t necessarily follow anymore…. if you’ve made a film that seems like a good fit for a certain distributor it can’t hurt to reach out to them directly.”

My thought exactly! So, going against popular wisdom that you needed an intermediary I decided to approach the distributors that I respected directly, like Oscilloscope and IFC as well as quite a few others. On the whole I was encouraged by their prompt, respectful responses. Some had interest, but ultimately nothing that was a full throated “yes.” Others offered the same kind of back-end deal I knew wouldn’t work for the film.

Frustrated, I reached out to some smart friends in the industry for advice. Gabrielle Nadig, producer of Little Woods, shared stories from other producers who said that, these days, even films with so-called names weren’t receiving big paydays or breaking even. She told me that she went with Neon for Little Woods because even though their offer “was not the biggest MG, they were the most passionate about the film.” And that matters.

But back to where I started this article: how can I recoup the costs of my microbudget feature? I learned from talking to producer Mynette Louie (Swallow) that a Netflix deal, for example, would be tough to get today. “Just a few short years ago,” she told “Netflix was aggressively acquiring finished independent films–they acquired four of my films between 2015-2017. But now they’ve shifted much of their business to financing/producing them. And other distributors, not just streamers but traditional theatrical distributors as well, have followed suit, so as not to be outbid when a film premieres, or to stake their claim earlier on quality projects.” Meanwhile, I also learned, foreign sales have evaporated and/or the numbers are suddenly so much lower than they were years ago.

I learned from my film friends that I wasn’t alone. Also frustrated by distribution opportunities available to her in 2019, Naomi McDougall Jones went the “direct-to-fan” model and took her feature Bite Me on a three-month, 51-screening 40-city tour, piecing together screening fees from indie cinemas and lecture halls. (You can check out her journey in her documentary on YouTube, which details all revenue streams and ticket sales about the tour.) Laudable, but exhausting to even consider. (Jones also has a hand in moviesbyher.com, a site launched by Sami Bass which provides a database of films by women.)

I reached out to Tiffany Boyle, President of Packaging and Sales at Ramo Law, after I saw her speak at a Stage 32 event. She agreed that the market was tough, and that currently sales agents are actually asking producers to oil the wheels by making it easier for sales to just produce what buyers are looking for. It continues to be the case that action/genre films have traction, but not all films are action or horror or fantasy, and even those indies are struggling. And these are not microbudgets like mine.

Looking at films that were similar in budget and “indie status,” I reached out to fellow filmmakers like Tom Quinn whose quietly moving Colewell played with #LIKE at Woodstock. It is one of the few projects I connected with that benefited from the production labs I mentioned; Quinn developed his script through Venice’s Biennale College and the IFP “No Borders” program. He told me his producers had established relationships with distributors so they didn’t need to bring on a sales agent. And they got (deservedly) lucky: “…We were thrilled, and caught off guard, when the film received two Spirit Award nominations. That gave us a tremendous bump.” Their film was picked up for distribution domestically with Gravitas, on all platforms, and for Blu-Ray/DVD, widening their audiences for this story about a female rural postmaster (as rural folk and seniors often don’t have access to streaming).

Also I dipped into my Film Fatales gang and talked with Roxy Toporowych director, of Julia Blue, to hear her experience. “The truth is that my film, even with multiple awards and having screened at a top ten festival, plus lovely Tier 2’s, had a hard time linking with a sales agent,” she said.” She connected to Cinema For All, a U.K. organization who offered her a community-based theatrical release there. For digital she initially opted for an aggregator, Distribbr, who subsequently went under, and finally wound up doing it herself via Amazon Prime. The film is now streaming in UK and USA. Lastly, she mobilized the Ukrainian community and held targeted screenings in various cities in the US. With all this the film almost broke even. “In the end, it was so important for me to have the film out in the world — films are made to be seen,” she said.” I was encouraged when she concluded, “Luckily, even if you don’t have a traditional plan, you can still do it on your own”.

And there is the Southern Circuit, another community-based theatrical route, recommended by Megan Griffiths (Sadie, Eden) and Liz Manashil (Speed of Life). Griffiths released her film DIY and blogged about the experience at sadiefilm.com. (Lots of good details to be found there.) After long chats we concluded that, for me, self-distribution would be the way to go. I’d have more control over the release, a better revenue split, and a shorter term with lower costs. ( Both Sadie and Eden, by the way, are with Giant Pictures, who I would describe as a “curatorial aggregator,” and Sadie is with BayView Entertainment for their DVD.) Manashil was also previously the manager of the now defunct Sundance Creative Distribution Initiative and is encouraging about her distribution relationship with Giant. “They’ve been supportive and honest and got my film onto Showtime in May,” she says.

So as #LIKE was finishing its festival run in early 2020 I was still juggling the varied distribution options, with a few small distributors in the mix and prepping my assets. Fortress of Evil did an amazing recut of the trailer using all the great pull-quotes of festival reviews and I used 99 Designs for the poster. Having found that distribution in the new Wild West of media land-grabs is very different than it had been even two years before, and that even theaters were becoming “a legacy thing,” I was considering a short four-wall for my theatrical. And then COVID-19 hit.

As well all know, it has sent shockwaves across the industry, affecting Hollywood films and microbudget filmmakers alike. Two days before her world premiere director Deborah Kampmier’s latest film Tape was knocked out of its theatrical run in NYC. But she and her team pivoted to a virtual-theatrical-premiere and on-line red carpet. She self-distributed these screenings using Vimeo OTT and Crowdcast, selling tickets for multiple nights with impressive guest Q&As after each screening. On the first night Tape garnered a global audience, arguably capturing more eyeballs through this event than it would have with a New York theatrical premiere or even a traditional streaming release. Kampmeier, is a problem solver. “What was a trend is now a necessity,” she said. “We as creators need to it meet somehow, and as indie filmmakers we need to monetize our work until we are on the other side.” Yup.

Heather Fink is another director who went with a different approach. She had placed her Inside You on the aforementioned Distribber and didn’t see a dime from its online life. But she got it back up on Amazon Prime herself: “But it’s pennies,” she told me. “I had thousands of viewers in the US and the UK — I believe about 30,000 views — and I made $50 from that. Five burritos worth. Not to knock burritos…” So she decided to just put her film on You Tube for free. “I knew I would feel so free and relieved to have the movie out there for free, worldwide, and not having to answer to anyone. I own the movie outright, and I may never have this freedom again.”

So what is left?

There is hope. A positive note from Tiffany Boyle arrived in my inbox: “100% sales are happening, finished properties have been selling – it’s good time to try to find that home…Keep thinking creatively, keep thinking of ways to keep pushing, people are reading this as a pause not a stop, hopefully this will open doors for folks who are working out of the box”.

When we emerge from our bolt-holes and comb our hair to face the world, will people go to the movies? After all, we are changing our habits during these months. Do we stop making movies? Do all directors go to work in TV (if they can) to pay their bills and live in the auteur world of the writer? Mirroring the old Hollywood system of the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s?

Louie worries about theaters post-pandemic. “…I’m not sure if they will ever get back to pre-pandemic levels,” she said. “But I think there will always be a segment of people who love the theatrical experience…The film industry was worried when TV was invented, then the VCR, but people still left their houses to see movies. Streaming is really nothing more than the next iteration of the TV and VCR, except now there is a ton more content to choose from and much better technology to deliver it. But just as people still go to see live theater, I think people will still go to see theatrical films. The question is how many people?” Indeed, and what additional experience is offered…

Hopefully for indie filmmakers after this period of our collective media-binge so much content will have been devoured that the beast will need feeding (!) and streamers’ and theater’s slates (virtual or not) will need to be replenished, and some smaller finished films like mine may make decent deals. But as one notable producer said, “We should just get the fuck out of this?… You kill yourself making a movie… no one makes money and no one is gonna see it. Not everyone’s voice is heard on streaming platforms.”

So as #LIKE is finishing out its (virtual) festival run in 2020 at NFMLA and the distribution conundrum is to be decided, Giant is looking damn good. And/Or possibly a virtual theatrical release, partnering with indie cinemas….

To be continued.

(I am also considering opening a drive-in, or at least write a TV series about one.)