Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“The Set was a Circle with the Floor and Mirrors Rotating”: Jan de Bont on The Haunting

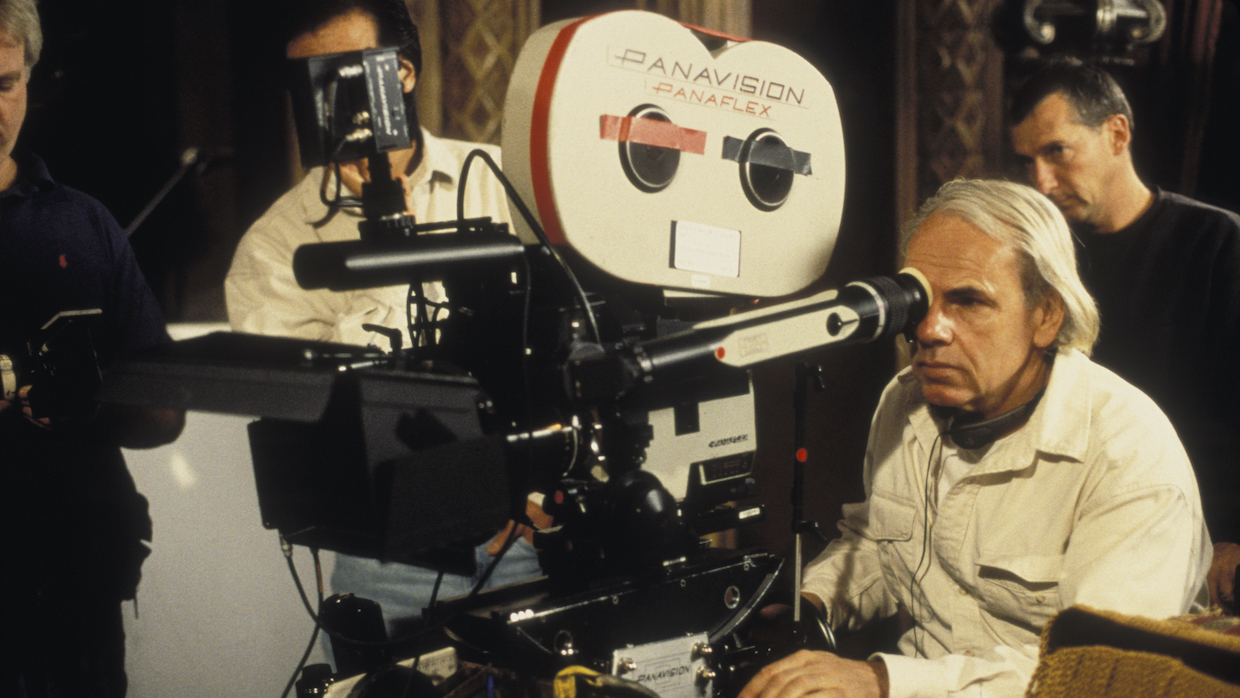

Jan de Bont on the set of The Haunting

Jan de Bont on the set of The Haunting Before he became a director, Jan de Bont was the cinematographer on some of the most visually intricate, elegantly lit movies of the 1980s and early ’90s, including Paul Verhoeven’s The 4th Man and Basic Instinct, John McTiernan’s Die Hard and The Hunt for Red October and Ridley Scott’s Black Rain. When de Bont made his directorial debut in 1994 with Speed, the film’s kinetic energy and precise attention to light and composition were no surprise; what made the picture a classic was how finely attuned the visual choices were to the nuances of performance. Speed made Sandra Bullock a star, confirmed Keanu Reeves as a viable action hero and was packed with colorful supporting turns by Dennis Hopper, Jeff Daniels, Glenn Plummer and the myriad performers on the movie’s out of control bus. At a time when larger-than-life, bigger-is-better action vehicles starring Schwarzenegger and Stallone were riding high, de Bont found commercial and critical success by humanizing Speed’s spectacle; he then directed a series of pictures that confirmed his status as a master of behavior-driven action movies enlivened by wit and an impeccably calibrated balance between design and spontaneity. Twister satisfied the demands of a Spielberg-produced summer blockbuster without smothering the very funny and often poignant love story at its core, while Speed 2 deftly turned a limitation—Keanu Reeves’ unwillingness to return for a sequel—into an advantage by making the film be about the psychological repercussions of Reeves and Bullock’s breakup.

In 1999, de Bont took another job for Spielberg helming The Haunting, the second screen adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. Wisely going in very different directions from Robert Wise’s 1963 film, de Bont turned Jackson’s source material into a nightmarish adult fairy tale focused on Eleanor Vance (Lili Taylor), a woman who has spent most of her adult life caring for an ailing mother. When her mom dies, the insomniac Eleanor joins a sleep study led by Dr. David Marrow (Liam Neeson). Marrow gathers Eleanor and two other subjects (played by Catherine Zeta-Jones and Owen Wilson, both lively and hilarious) at the foreboding Hill House, a haunted estate where he hopes to secretly study their physical responses to fear. When the mansion comes to life, The Haunting takes unexpected turns as Eleanor finds a sense of comfort and belonging in the house while the others just want to get out alive; in typical de Bont fashion, the protagonist’s complicated emotional state is seamlessly integrated with the action and the requirements of the genre, resulting in a hypnotic, evocative piece of rousing entertainment that lingers in the mind long after it’s over. A few weeks ago I wrote about a new Blu-ray release of The Haunting for my home video column, and after revisiting it I couldn’t stop wondering how de Bont achieved some of his effects – not just the traditional special and visual effects, but the unique blend of naturalistic performances and immaculately orchestrated fantasy. After rewatching the Blu-ray (which, in addition to an excellent new transfer includes some terrific behind-the-scenes material), I hopped on the phone with de Bont to ask him about his process.

Filmmaker: One thing I love about The Haunting is how strong the sense of point of view is when it comes to the camera. In your movies the camera is never just a passive observer, nor does it get in the way. It’s a tricky balancing act. What was your philosophy in terms of when and how to move the camera?

De Bont: I wanted the camera to be almost like an accidental viewer, like somebody who happened to be in the building while all this was taking place. I didn’t really want it to be like a typical horror movie where you announce things like, “Don’t go in the kitchen” and the characters go there anyway. I always felt that if the camera moved like a person that would allow the audience to share its point of view and see the story from a very personal perspective, then they would get a better idea of how the characters in the movie feel, especially Lili’s character. The interesting thing is that there’s nothing scary for her about what’s happening; she is slowly but completely engaged by this world. That’s a very different point of view from what you often get in a horror movie, and it requires a certain amount of emotional detail that you can only get if you engage the viewer with the camera itself. Because the camera always has a point of view—not only my point of view, but Lili’s emotional point of view, and it’s a slow build as opposed to the momentary hardcore shock effects you get in other horror movies.

Filmmaker: How did your lens choice play into that point of view?

De Bont: Because the camera is from a human point of view, it cannot be either super wide or super close, and you have to be fairly constant. The same size lens, the same kind of focus—in this case a 50mm anamorphic lens, which in my experience relates to a person’s direct point of view, as if it’s just a bystander. So we almost never use a wide angle lens or a telephoto lens—it’s always that same 50mm, and I used lenses that were a little softer, a little more painterly, for almost everything relating to Lili and her emotional experience.

Filmmaker: How did you come to cast Lili Taylor? She’s great in the movie, but she wasn’t a big star at the time and this was an expensive studio film. Did you get any resistance?

De Bont: Oh yeah, they initially wanted a star, but I thought if it was a star I wouldn’t really believe it. I feel like when you have a star, you’re always looking at the star, and I needed an actress with a kind of open-minded vulnerability that was curious and full of life. Lili is such an amazing actress that she completely became this girl from beginning to end of the shoot—everything I imagined reading the screenplay, you could read it all on her face. When you watch the movie you can see her internal feelings and the process she’s going through, and it’s believable because you’re not distracted by fame. For something like this too much star quality would be disorienting. I was really, really happy that we were finally allowed to use her.

Filmmaker: Well, one thing I’ve noticed in all of your movies is that even when you’re dealing with larger than life action, you really root the performances in reality. Not just psychologically but physically—it always looks like the actors are really doing whatever they’re doing. Even in your big action movies like Twister you’re usually not using conventional big action stars.

De Bont: When I was a cinematographer I worked with many, many directors and what I always found is that if you use a big star, that star is often in the way of the character. When I did Speed, I was very happy to get Keanu, because at the time he wasn’t really an action star; in fact, he didn’t really like action. He was afraid of it, and that meant when he had to do things you could see how uncomfortable he was and really feel it, and therefore it becomes much more realistic. I like the actors to do their own stunts—not the dangerous ones, but a lot of these things the actors can learn to do themselves. I usually convince them things are safe by doing them myself, and I’m not a very athletic personality; if I show them that it can be done and then they do it, suddenly the acting disappears. It becomes a natural form of response based on real adrenaline. If you’re behind a jet engine and you’ve got wind and debris flying at you, you don’t even have to think about acting, it comes automatically. So, you get performances that are really unique and very, very believable. I think it is a key element in action movies. Personally, I have major objections when I see actors acting in action movies, and it happens all the time because you know they’re not doing it. I know from experience they’re not doing it. Their reaction is not real, but if you put them in circumstances that look dangerous and are physically engaging for them, their acting mixes with a pure emotional reaction and it becomes much more believable to an audience.

Filmmaker: I would think that in The Haunting, it also helped the actors to be on those incredible sets designed by Eugenio Zanetti. How did you decide on him as your production designer?

De Bont: Yeah, he was an unusual choice for a horror movie, but I thought of this more as an opera. I wanted the set to be as much a character as the lead actors, so I needed someone who had done something like that. My research led me to Eugenio, I explained to him what I was looking for and the set he came up with was absolutely spectacular. It was so huge it wouldn’t fit on any soundstages—we had to build it in the airplane hangar where Howard Hughes used to store the Spruce Goose. When you step onto that set, it is overwhelming and there’s no way you cannot have an emotional response—it immediately puts you in the right mindset. There’s nothing an actor has to do, they just feel right away that there’s something really special going on in this house. That it is a little bit alive in a way that everywhere you look, there’s something else to see. You’ll see something different each time you turn around a corner. And it’s very beautiful, which is what I was looking for—Lili’s room is full of elements that would be extremely scary to some people, but to someone else they might be attractive because they’re so beautifully made. I didn’t want it to be an overtly scary room, because that’s not the way Lili looks at it. For her it’s all beautiful and unique and represents a different life from what she’s been stuck in. She is overwhelmed in a very positive way. The most difficult thing was that the room had to come alive slowly; all the sculptural and architectural details had to be designed in a way that would work with all the special effects that were happening on camera, as well as with the visual effects added later. It all had to be designed in a way where the room could move gently and respond to her state of mind.

Filmmaker: Another amazing set is the rotating room surrounded by mirrors. How on earth do you shoot something like that? Where do you put the camera?

De Bont: Quite often when you have mirrors, cameras tend to go higher or lower to avoid seeing any reflections. But if you do that, you lose the right perspective—you don’t convey what those characters feel when they are in the room themselves. You have to be at eye level, so you have to basically film through mirrors, with the camera hidden behind a mirror that you can move along with the camera. It wasn’t always easy to do, because the floor was also moving. There was no way to hide the camera, because the set was a circle with the floor and mirrors rotating. Using vertical elements like pillars, as well as a mirror, we were able to very carefully avoid seeing it, but it was not easy, let me tell you.

Filmmaker: That leads me to a question I’ve always been curious about when it comes to your work. What is your relationship with your cinematographers like given your extensive background and experience in that area?

De Bont: This is a question I’ve been asked multiple times because people always assume it would be difficult, but in my experience it’s actually really easy working with other cinematographers. I can see when things are difficult and when the cinematographer needs more time to light. I always support him. One time I was the cinematographer on a movie where the director had been a cinematographer before, and that wasn’t so easy because he was really set in his ideas about how things had to be done. It would have been better for him to hire just a worker who would do exactly what he wanted without contributing. I’m not that type of cinematographer. I really like to contribute and enhance the visuals, and when I’m directing that’s what I want from my cinematographer. I don’t want them to only follow my vision, I want them to come up with other ideas too. We talk a lot about what the style should be and how I like the light, but I don’t dictate how to do it.

I do, however, operate the camera a lot when I’m directing, and that goes back to the very specific relationship I have with the actors. If I have an immediate reaction to what they’re doing I want to be able to whisper to them, and I want to move with them depending on their response to what’s happening around them. It’s really important to me to be an active participant in the scene and not just record it, and it’s important for the actor not to feel limited. I like to operate with a flex arm, which is like a little mini-jib where the camera is balanced and I can move all around, 360 degrees. That way actors don’t have to hit marks—I’ll follow them wherever they are and they can go wherever they want to go. You cannot be limited to marks. Marks will kill you, and they’re distracting to me as an audience member. I can tell in many movies when somebody walks from mark A to mark B, then turns around and that makes it awkward to get to mark C. I can really see it in a movie.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and streaming on Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.