Back to selection

Back to selection

Seeing Eye to Eye: Color Correction Styles Across Today’s Film Restorations

Hurlements en faveur de Sade (Eclair restoration)

Hurlements en faveur de Sade (Eclair restoration) Going to the cinema to see a 4K restoration or buying a Blu-ray of a beloved classic from a boutique publisher, one is never quite sure what one will get, colorwise. Frequently, a distinctly tinted veil seems to have fallen over the screen from the first frame. Sometimes, this is a chilling greenish blue, one that bronzes flesh tones and adds a steely, Melvillean atmosphere to the proceedings. On other occasions, it is yellow, as if golden hour had found a way to fall day and night, indoors and out, then curdled from its newfound monotony into a stubborn, pissy stain. The cars in a Chabrol, Mambéty or Vecchiali film will all of a sudden threaten to sprout arms, legs and pithy banter under the influence of a teal and orange color scheme more immediately evocative of the Transformers saga than a 1980s or ’90s African or European drama. And then, sometimes, a balanced spectrum appears, complete with everyday luxuries: deep blacks, natural flesh tones, blue skies, red blood, white snow.

Today’s cinephiles are regularly confronted with these conflicting visions of cinema’s past, while at the same time asked to quietly, unquestioningly accept the whole, to trust the experts, artists and market. Faced with this scenario, a viewer may feel something like Michel Piccoli’s Paul in the famous early scene of Godard’s Le Mépris (1963) in which he lies in bed alongside Brigitte Bardot as Camille. She catalogs her own nude figure, asking Paul whether he likes her feet, her ankles, her thighs, her ass, her shoulders, her breasts, her face, while a mysterious filtered light alternately bathes her nakedness in the red, white and blue tones of the tricolore. In reply to Camille’s final question, “Do you love me totally?,” we must perhaps, with regret, amend his answer: “Yes, I love you tenderly, tragically. But not totally.”

For about a decade, film restoration has been a largely digital affair. After the best available materials have been identified, secured and scanned to create a digital intermediate (or DI), almost all the restoration proper is achieved using digital tools in a fully digital workspace. Though a restored DI, when budgets and policy allow, will sometimes be transferred back to film for the creation of a new negative or positive prints (celluloid remains a more stable medium for long-term archiving), the forging of new digital masters has become film restoration’s default and inevitable end goal. These masters are also what make contact with the public as DCPs projected in the last populated caverns (cinemas), Blu-ray fetish objects or a lunar cycle’s selection of streaming offerings. Hundreds of these rejuvenations and rebirths are delivered every year, by labs great and small, industrial and DIY, all around the world. However, the lion’s share come from a handful of powerhouse labs—notably, the Hollywood majors’ in-house outfits in the United States, L’Immagine Ritrovata/Cineteca di Bologna in Italy and Eclair in France.

When I first noticed the house styles, it wasn’t as such—as persistent patterns of obscure origin or the disconcerting appearance of one master’s initials on another’s painting. Instead, these recurring tintings flattened and homogenized the images, deadening my experience of a film. This is a necessarily subjective observation, but not a unique one. My ability to interpret and appreciate a film’s spatial dynamics was affected, as were my emotional responses, pulled along with unilaterally warmer or cooler color toward a particular mood, and then exhaustion or boredom. Natural, balanced whites had disappeared, and I missed them. In more extreme cases, where the color space had noticeably diminished, certain shades took on an undue and unpleasant prominence—making, for example, certain dull reds or bright blues into insistent and distracting objects that my eye chased around shots and the montage as inevitably (and far less pleasurably) as the red teapots in late Ozu films.

No stranger to watching films in less than ideal condition, from torrented VHS dupes of 16mm films taped off basement walls to prints faded over centuries into Pepto-Bismol pink, I have little trouble getting on with my life and making mental corrections to a viewing experience, imagining what it could look like while also appreciating the unique aura of the corruption I’m facing. But this is incredibly hard with DCPs and Blu-rays. These are not unique objects but infinitely, perfectly reproducible ones that are very likely to be the only way the film in question is experienced for the foreseeable future—or at least until its next restoration. There is also the fact that, by most yardsticks, these restorations are quite good, usually maintaining high standards of definition and free of scratches, jumps, flicker, fluctuation, tramlines, pops and crackles. This very proximity to the unattainable ideal object gives any minor but describable deviation a strange prominence, undermining the experience in a way not unlike the uncanny valley effect. It is similarly alienating and illusion- shattering—it almost looks good enough to be true, but something is not quite right.

Most digital restoration tools appeared before or soon after the advent of the digital rollout of 2012, parallel to similar and interrelated revolutions in other sectors of the film environment, from filmmaking’s switchover to digital cameras and post-production to exhibitors’ adoption at knifepoint of digital projection and the DCP standard, usually with an attendant loss of 35mm capabilities.1 The intervening years have mostly seen refinement and variation of a basic toolkit that includes stabilization, clean-up, denoising and interpolation software (though that may change, for better or very likely worse, with Tropical Storm AI beginning to break).

None of these has been more fundamental or far reaching in its uses than digital color grading, which has served to revive wan tones from faded prints, to seamlessly unify elements stitched together from multiple sources and simply to bridge, as much as possible, the inevitable gap introduced between celluloid and its flat digital scan. Color grading is also “the practice that has been affected the most by the introduction of the DI process,” as noted by Giovanna Fossati in From Grain to Pixel, a prodigious, exhaustive survey of the transition to digital archiving first published in 2009 and most recently updated in 2018. Photochemical color grading was a process with stringent rules and limitations, effected mostly through the use of colored lamps during film printing, supplemented only occasionally or experimentally by additional techniques such as the bleach bypass.2 Digital color grading is significantly more powerful than its photochemical ancestor, allowing for, among other things, the selective adjustment of certain areas of the frame or of a single color component (red, green, blue, yellow, cyan or magenta) independent of all others. The digital palette is comparatively limitless—and when faced with a limitless horizon, human beings usually set up camp.

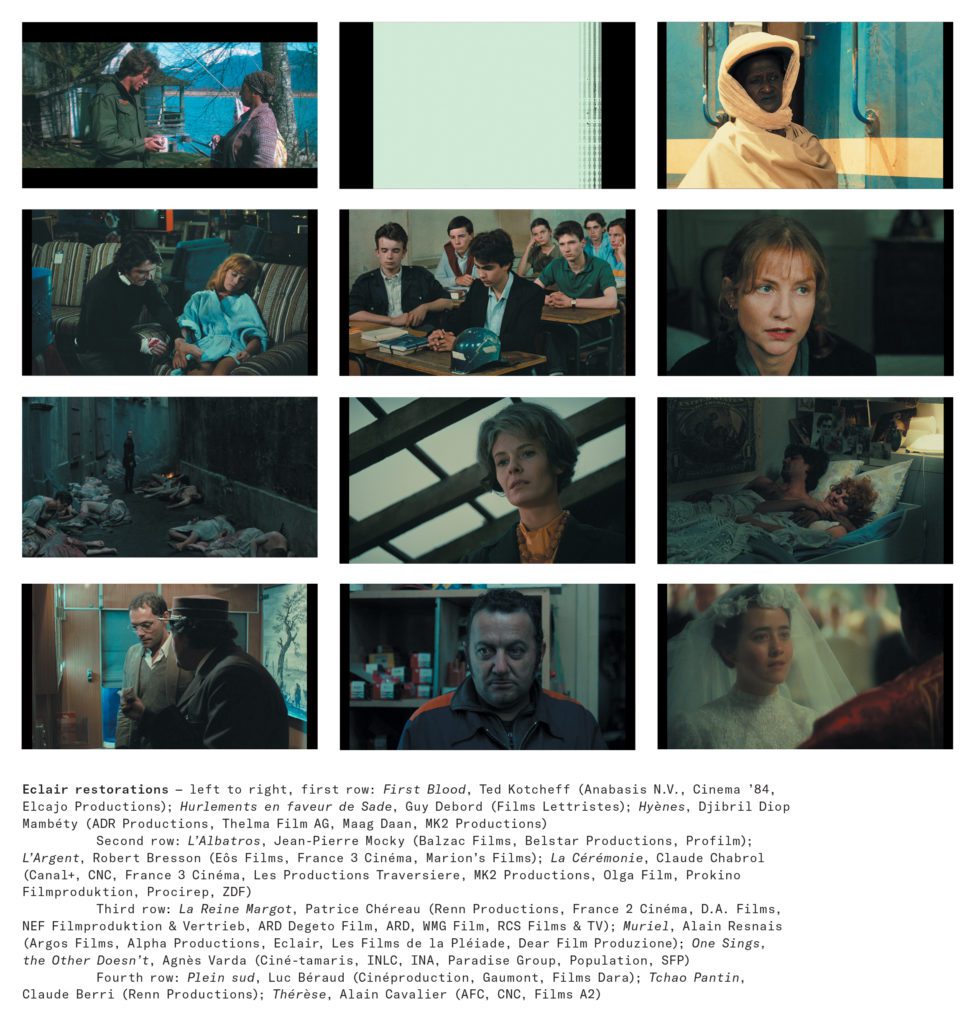

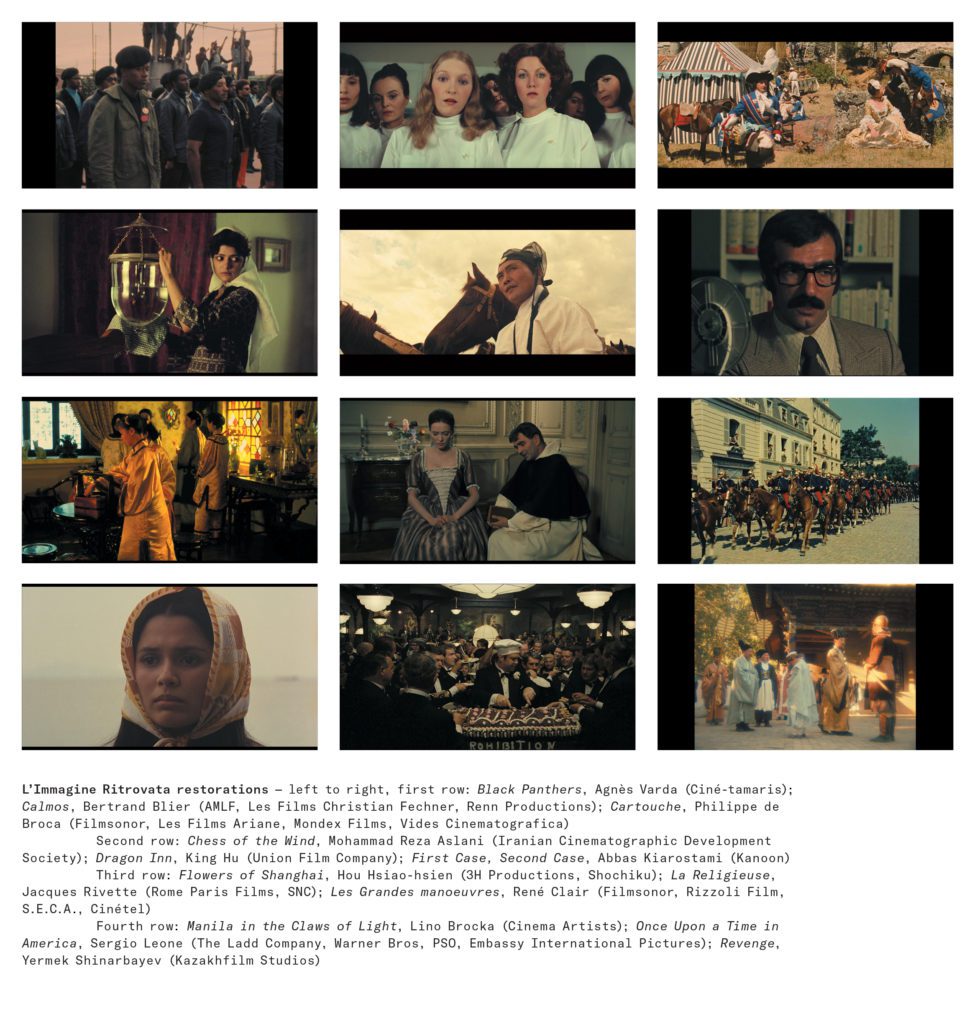

In some senses, this has been a change for the better. Today, many colorists doing restoration work make a conscious effort to limit their digital interventions, by and large, to what would have been possible in the old photochemical sandbox, simulating not only the color of the release print, but the tools it would have been created with. However, time has also served more ambiguously, for the creation of norms, conventions and habits of usage. Nowhere is this more apparent to a careful observer of contemporary restorations than in the appearance of a wide variety of distinctive and groupable color signatures. Noting the labs responsible for a distinctly tinted restoration, it becomes clear that certain houses have a style, a color profile or signature that marks the vast majority or all of their work that, once identified and described, is often instantly recognizable. The French lab Eclair, for example, is usually dedicated to the aforementioned steely blue tint, with occasional forays into the closely neighboring teal and orange scheme. Italy’s L’Immagine Ritrovata, on the other hand, is partial to a sepia-ish, light-yellow look, as well as a noticeable overall darkness or dimness. At Murnau Stiftung in Germany, a leathery brown has become the color of the last century. American studio films, usually preserved by in-house labs or outsourced to relatively small domestic houses like New York’s Cineric, less often bear these signatures, tending to present balanced whites and a full range of color within Technicolor or other processes’ parameters, though there are exceptions.3

Once the territories of some of the labs have been delineated, new complications, quirks and characters of the larger landscape come into relief. Some examples:

— Rivette-ian conspiracies: Duelle (1976), restored in 2K by Technicolor in Paris and released by Carlotta in France and Arrow in the UK and United States, is distinctly yellow almost throughout, nearly erasing an effect seen in previous editions of the film whereby two characters are dressed in contrasting silver and gold costumes symbolizing the moon and the sun—here, the sun reigns supreme. Meanwhile, monochrome sequences that had previously appeared to employ a filter for a strong blue tint are now rendered in black and white. Ritrovata’s restoration of La Religieuse (1966, released in the United States by Kino Lorber) is indelibly marked by the lab yellow, and while Hiventy’s versions of the two Jeanne la Pucelle films (1994, released in the United States by Cohen Media) don’t bear a signature firmly, if at all, they are, alarmingly, lacking sections of day-for-night tinting found in previous releases.

— Guy Debord’s aggressively minimalist feature Hurlements en faveur de Sade (1952) originally consisted of a collaged soundtrack set entirely to strips of black or white 35mm leader. As restored by Eclair, the whites are now a charming pastel green. (After Jarman’s Blue (1993), Debord’s Mint Chip.) A dead giveaway and revealing detail, here and elsewhere, is that the tint is present even in the newly appended “white text on black” title card providing restoration details at the start of the film.

— There are cases where a distributor, especially of Blu-rays, will license a restoration that has been previously released (usually in other territories) but put it out with a different or adjusted color timing on their own disc. We can guess, but not assume, that this is done because of concerns about the historical accuracy of the materials delivered to them. It is also unclear whether these adjustments have been made to an untimed flat scan also made available to the distributor or from the lab’s restored version. Examples include Kino Lorber’s starkly different 2018 and 2022 releases of Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), both ostensibly sourced from the same Ritrovata restoration, and Arrow Video’s UK release of Ermanno Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978), also based on a Ritrovata restoration and/or scan, but much warmer and more white-balanced than the previous Criterion Collection release of the same.4

— The Olmi film is an intriguing example. The Criterion, with a more evidently unbalanced color profile, is the only release supervised and approved by the director—and its colder, blue-ish tone more closely matches recent digitally shot and colored Olmi films such as Greenery Will Bloom Again (2014) than it does Arrow’s disc of The Tree of Wooden Clogs, older DVD releases or even Ritrovata’s yellow color signature. However, this is an exception to a general rule. Where a lab has a signature in place, it would seem to appear regardless of the supervising presence of a creative authority, such as the director or cinematographer. A few of the many examples: Flowers of Shanghai (1998) and Taipei Story (1985)—both restored by Ritrovata, the latter supervised by Hou Hsiao-hsien and released by Criterion; Dragon Inn (1967) and A Touch of Zen (1971)—both restored by Ritrovata, the former supervised by DP Hui-ying Hua and released by Carlotta (FR), Criterion (US) and Masters of Cinema (UK); L’Argent (1983)—restored by Eclair, supervised by Mylene Bresson and released by Criterion; Chess of the Wind (1976)—restored by Ritrovata, supervised by Mohammad Reza Aslani and DP Houshang Baharlou and released by Criterion.

— Outside of DVD and Blu-ray message boards and a few more general articles,5 the color signature phenomenon has gone under-discussed publicly, even in the majority of home-video reviews. However, on certain private torrenting trackers dedicated to arthouse and international films, the signature styles have been met with skepticism from the start. More recently, some users have taken to uploading “custom color” versions of certain films, retimed from restorations in a similar manner to the variant home-video releases mentioned above, and doing what they can to return more neutrality and whites to, for example, Patricia Mazuy’s Peaux de vaches (1989, Eclair), Chantal Akerman’s Golden Eighties (1986, Cinematek), Hou’s Flowers of Shanghai (1998, Ritrovata) and Mark Rappaport’s Mozart in Love (1975, George Eastman House).

— An exception to the rule of general indifference has been the recent suite of Wong Kar-wai restorations released by Janus/Criterion theatrically and as a seven-feature Blu-ray box called World of Wong Kar-wai. All seven films were restored by Criterion with the aid of Ritrovata and One Cool, under Wong’s close supervision, simultaneously undergoing changes ranging from adjusted color timings to aspect-ratio switches and new sound mixes and credits sequences. Despite DP Christopher Doyle’s plea to cinephiles to “let go,” the backlash was immediate and raucous, especially about the easily demonstrable changes to color, with calls from many corners for the digitally revisionist director’s head on a (35mm) platter. Few noted the irony or ambivalence toward artists suggested here: a beloved filmmaker openly making changes with clear and stated artistic intent (however regrettable the results may at first have seemed) being met with scrutiny and vitriol, while the color of potentially hundreds of films every year is, one worries, being diverted from historical accuracy and artistic intention with barely a ripple on the surface of the internet and cinephilic discourse.

—Another recent Criterion box set, the ambitious 15-disc The Complete Films of Agnès Varda, compiles dozens of restorations—some accomplished by Eclair, others by Ritrovata. Thanks to the contrasting blue and yellow signatures, visible even on films like One Sings, the Other Doesn’t or Vagabond, where Varda and DP Charlie Van Damme supervised the work at Eclair, it is immediately apparent which lab was responsible for which films.

Much of this multicolored sea has been charted thanks to Remy Pignatiello, a French industrial engineer who first noticed strange undercurrents while watching Philippe De Broca’s That Man from Rio (1964) on a Blu-ray made from an Eclair restoration. As, disc after disc, that tint and other shades haunted him like Marnie’s traumatic red, he began to gather information and to compare notes on message boards. It became clear that the signatures were widespread, affected hundreds of films and only started to appear in strength around 2013 or 2014, shortly after the digital rollout but well into the Blu-ray era of home-video.67, Hearing various explanations and justifications for particular cases, he patiently compiled these as well. Along the way he launched TestBluray.com, a Blu-ray review site maintained on a nonprofessional basis. It was here that he recently published “Restauration et étalonnage: questionnements techniques par temps modernes” [“Restoration and Color Grading: Technical Questions for Modern Times”]8, an invaluable, even-handed and conscientious exploration of the color signature phenomenon, serving double-duty as a growing compendium of known cases, organized by lab, and an essential read in either French or Google translation for anyone at all interested. Examining several examples closely, and building off of years of investigation as well as numerous conversations with colorists and labs, Pignatiello picks up each of the more totalizing arguments that would explain away the phenomenon, puts them to various tests and finds that the signatures:

“cannot therefore be explained

— by an aesthetic logic specific to an era (’60s, ’70s, ’80s, etc.), because they span almost 50 years of cinema.

— by a geographic logic because the cinema of the whole world is concerned (even if Ritrovata restores many Italian films and Eclair French ones).

— by a human or technical logic because all types of production, countries, film genres, directors and technicians are concerned. Moreover, they survive the supervision/approval of technical/artistic authorities.

— by a logic of rights holders with specific demands or requests because at least 10 catalogs are concerned.”

Pignatiello is careful to stop there, identifying the issue without making any firm claims about its causes or cure. He gestures in some likely directions, notably the use of look-up tables, or LUTs, conversion tables that are used in color grading to establish the starting parameters for a section or a film’s duration—effectively acting, as a Ritrovata colorist would describe it to me, similar to an Instagram filter. But Pignatiello is above all sober and diplomatic, carefully avoiding speculation that would distract from his main points: that the issue exists, and that it is an issue. His argument for the latter point is concise: These signatures, whether Ritrovata’s and Eclair’s or almost any other pair of labs’, are incommensurable with each other. They cannot, for example, both be right about French films shot in the ’70s on Kodak stock—their respective styles differ too much and too markedly to claim equal right to historical accuracy. He is not (nor am I) in a position to make any definitive statement about what the correct timing is, whether Eclair’s, Ritrovata’s, a more balanced approach as favored by many American labs or some other option entirely. However, the continuing existence of the signatures, and the disagreement implicit in the wider picture, proves that this is an issue affecting, one way or another, hundreds of films annually.

I feel confident that in time, the problem will be recognized, addressed and that, consensus reached, certain styles will not just fall out of use but become, beyond the signatures of particular labs, the hallmarks of a certain era of film restoration, as recognizable to future colorists and cinephiles as the tints of various antique varnishes are to today’s painting restorers. However, with this recognition, suddenly hundreds of restorations, representing thousands and thousands of hours of conscientious work on the part of restorers, could be rendered out-of-date, effectively obsolete—and not for the usual reasons of insufficient or outmoded technological means. There is also the inescapable fact that the resources of film restoration are limited, that not all the films that one would like to be restored are restored or can be restored and that all of the films most vulnerable to falling through the cracks are likely to continue to do so, especially as the opportunity to capitalize on the same classics in sparkling new restorations again presents itself to distributors.9 That this all will happen someday seems to me more inevitable than likely, so time is of the essence—the sooner the issue is addressed, the less damage, the less work that will have to be done to repair it, the greater the resources that will be available to move forward.

So, how to do that? I spoke with two colorists whose many points of divergence and convergence, as well as the obvious care, scrupulousness and intelligence with which they both approach their work, could perhaps help map the answer. The first was Daniel DeVincent, who has been working at film labs since the late ’70s. His initial positions were as a color timer and printer in a then entirely photochemical environment, and it was in part because of his close familiarity with the old processes that he was brought into his current role as senior colorist and director of digital operations at New York’s Cineric. Here his projects are mostly Hollywood films of various vintages, often in close collaboration with Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation. He uses LUTs, as described above. However, his first port of call when embarking on a new restoration is to look for two things: “Where do the blacks sit, how much information should you see in the blacks? And [that] the whites do have a balanced sense to them. They have a huge impact because it’s going to affect the whole color palette from white on down. If you make the whites yellow, everything is going to be yellow.” He is also of the opinion that balanced whites do appear in most of the well-maintained archival prints he uses for reference. While making close comparisons with these, he goes about determining whether a particular shot or scene should be “darker, lighter, its feel, tonality.” He consciously focuses on these terms instead of ones with a more explicit color bias, like the commonly used “cooler” and “warmer.” His watchword is simplicity, taking care not to overstep. He disavowed any intention to create a signature of his own or Cineric’s, and was not aware of this occurring elsewhere, but expressed concern about that possibility once I raised it.

I also spoke with Giandomenico Zeppa, the senior colorist and head of color grading at L’Immagine Ritrovata—and also the head of the same department at Eclair Cinema, which in a strange twist, was acquired by Ritrovata in 2019. However, as he pointed out, the labs mostly maintain their autonomy. Zeppa will occasionally be asked by his higher-ups to advise more closely on Eclair projects, but he maintains the Italian lab as his wheelhouse. Before his 16 years of experience as a colorist, Zeppa’s background was in film studies. Like DeVincent, he has often worked with the Film Foundation, and his goal is to approximate, as closely as possible, the experience of a film projected theatrically on its initial release, “to simulate the original technical workflow in digital, the post-production processes at the time.” Like DeVincent, he uses LUTs that primarily simulate a single element of the larger production apparatus: “the film support,” the positive film stock the film would have first been printed on. However, he feels individual stocks often have strong inherent characteristics, which he prioritizes matching over attempts to pinpoint for example, balanced whites. He does his timing while simultaneously watching a release print (whenever possible), adjusting the DI as best he can to match what he sees projected. He applies his LUTs in place as one of the very first steps after starting with a flat scan. This, too, seems to be standard industry practice. They are in place already when the restoration is screened for a director, DP or other “film witness,” as he terms both those human elements and the vintage prints he tries to stay faithful to. That LUTs are usually introduced so early in the workflow may go some way toward explaining how so many restorations are both “authorized” and “signed.” However, though he does recognize a yellow tendency in his LUTs and the resulting restorations, this is far from thoughtless or an attempt to leave his personal stamp—he says that this yellow reflects the color character of the Kodak stock that nearly everything was originally printed to.

I don’t agree with him. I’ve watched hundreds of films from every era and region on release prints, presumably many of them on Kodak stock, and especially the European films of the ’60s through the ’80s that are Ritrovata’s bread and butter. I recall that some did have a yellowish character that was like or comparable to that of the Ritrovata restorations, but these have been a small minority compared to a more balanced majority—in my subjective (and logistically difficult to verify) view. Nor am I sure that Zeppa’s process adequately contends with the fact that, as Fossati points out in From Grain to Pixel, “in most cases all original elements of a film have suffered the same sort of color deterioration, and as a result, a truthful benchmark for reconstructing the original colors no longer exists.” This contention, while not in any way qualifying the need for “film witnesses,” should put us on our guard about vintage prints’ possible or probable unreliability. Zeppa made it clear to me that he is aware of these dangers, but the results, in my opinion, may perhaps still disproportionately privilege the vintage stock’s testimony—especially as it is the starting point of the LUT to which all other variables are then put in relation.

However, speaking with Zeppa and feeling his profound love of his work, his infectious cinephilia, his dedication to thorough research and what he terms a “philological” approach to restoration, as well as his generous, frank and insightful consideration of the questions and concerns I raised, I found myself impelled to reflect on his arguments at length and, finally, unable to dismiss them. Thankfully, it is not in this article’s domain to settle the matter. It is a hugely complicated question, requiring, among other things, the sum total of our “knowledge of the historical context from which the work to be restored originates, of the technology used to produce it, as well as the knowledge of the work itself and of its maker(s)” (Fossati), for which we cannot hope to retrieve the one true answer—the original state of the film upon release that is now lost to us by time—if such an answer ever existed. What we can hope for is a range of acceptable, coexistent answers, produced by individual colorists with their own unique strengths, backgrounds, researches, intuitions and workflows, but brought into proximity by shared knowledge, agreed-upon standards and a dynamic understanding of film history.

DeVincent and Zeppa agreed on other things. One was that there was very little communication between labs and that each tended to operate in relative isolation, developing research and restoration methodologies as well as their proprietary LUTs behind firmly shut doors of industrial secrecy. Another was that this is unfortunate. Zeppa lamented the lack of public discussion of color restoration; for example, its conspicuous absence as a subject for panels at film festivals, even ones highlighting or dedicated to restorations. He also noted the competition between labs over funding, projects and clientele, and the way in which this creates structural obstacles to collaboration and conversation, as much as those might be desired by individual or even a majority of colorists. DeVincent and Zeppa also agreed that, if the signatures exist, this is a structural problem, clearly much larger than any one lab or colorist, and that if there were to be any hope of addressing it, this would have to be through a pooling of knowledge and expertise across the restoration industry.

In the early days before and during the digital rollout, various national, pan-European or global initiatives, organizations and consortiums emerged or came to the fore to aid in the difficult but essential work of setting standards, developing shared tools and establishing guidelines for the new frontier—among them the Future of Film Archiving, the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers and the International Federation of Film Archives. This was also the time of initiatives on the part of companies like Kodak and Technicolor that developed, for example, suites of LUTs (Kodak Look Manager and ACES, respectively) that simulated their photochemical products or processes, and that were then made widely available for labs to adopt for their own purposes. However, since this burst of collective activity a decade or more ago, these discussions and overtures have mostly dimmed to murmurs, especially around the subject of color. The colorists doing the work want to have that conversation, and films and film history are owed it. One hopes it will begin soon, whether online, at a film festival panel or under the auspices of a fully-fledged consortium of colorists, archivists, historians, color scientists, filmmakers, film manufacturers and distributors, and we can all once again enter the cinema, take our seats and see something like eye to eye.

1. A coup zippily documented in Will Tavlin’s recent piece for n+1, “Digital Rocks”: https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-42/essays/digital-rocks/↩

2. A way to achieve a distinctively desaturated, silvery look, invented by Kazuo Miyagawa for Kon Ichikawa’s 1960 Her Brother but not popularized until its adoption by Hollywood in the 1980s.↩

3. Several distributors were approached for this article, including Kino Lorber, Criterion/Janus and Arrow. They were either unresponsive or declined to comment.↩

4. These known cases of postlab alterations open up another possibility: that on some limited occasions it may be rightsholders or distributors who are creating color signatures by consistently making changes to restorers’ work after delivery.↩

5. For example, Robert Drucker’s “Film Restoration Today: The Elusive Perfect Viewing Experience,” https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/film-restoration-today-the-elusive-perfect-viewing-experience.↩

6. The High-definition Optical Disc Format war ended in 2008, when Toshiba conceded defeat on behalf of HD DVD’s forces.↩

7. When the signatures first appeared, it was often speculated that they were an attempt to “modernize” older films, to bring them in line with the dominant visual trends of the day, specifically the “teal and orange” color timing then ubiquitous in Hollywood, as well as much of arthouse cinema. However, it is interesting that shortly after this, film production began trending back toward balanced, naturalistic color, while stylized palettes became more and more common in restoration. One of the last really hardcore examples of the mainstream teal and orange trend was George Miller’s 2015 Mad Max: Fury Road, a maximalist specimen of so-called late style that, tellingly, was later released by its director in a black and white version without appreciable violence to its legibility or meaning.↩

8. https://testsbluray.com/2021/05/08/restauration-etalonnage-questionnements-techniques/↩

9. It should be noted that Ritrovata and Eclair are not just Europe’s foremost labs, they also handle a great number of restorations of films shot outside of their respective countries, including classics from South America, Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. Often, these films have been dependent on the funding and support of Western European states and film industries for their entire lives, from their initial production through their festival runs and theatrical distribution, and remain similarly dependent, and dangerously vulnerable, in their afterlife as preserved or preservable objects.↩

Correction: A previous version of this piece misattributed the 2013 restoration of L’Homme de Rio to Digimage/Hiventy. It was done by Eclair, and the text has been corrected.