Back to selection

Back to selection

How to Maintain Your Body in the Camera Department According to Movement Specialist Liz Cash

Liz Cash giving a presentation

Liz Cash giving a presentation In “The Body is a Tool,” I talked with DPs and camera operators about the routines they developed to maintain their bodies against taxingly long days on set. When even film workers’ unions provide few resources to prevent bodily harm, crew members create their own devices, so methods of self-preservation tend to vary greatly. This was true of both the four camera people I talked with for the article and many of the set workers I’ve encountered in production. In this environment, a Steadicam operator might recommend a vest for no reason other than it worked for them personally. There are no clear, standardized metrics for what tools and methods work for what bodies; individual experiments tends to isolate and dissolve, never fossilizing into a collectively useful reference point.

Having absorbed contradictory advice, I was relieved to discover the work of Liz Cash, a NYC-based movement specialist, or strength and conditioning coach, who specializes in the needs of film crew. She is a rare authority on bodily injuries caused or exacerbated by set work. Prior to pursuing a doctorate in physical therapy, Cash was a camera assistant for over ten years. As a particularly bodily unaware ex-camera person, I learned much from our conversation that I will carry into my day-to-day.

First, she offered me her top three things to consider when trying to reduce bodily pain: finding the right footwear, resolving breathing patterns (make sure they’re non-compensatory) and resolving your body’s asymmetries. She dives into each of these factors in great detail, provides evaluative tests you can try yourself at home, as well as tips for getting through the long weeks of production.

Filmmaker: Can you provide an example of an injury you’ve treated for a client to help introduce and visualize your process?

Liz Cash: A client came to me with Achilles tendonitis pain. He had had it for about a year. He’s a Steadicam operator, and he had gone to his doctor previously to seek treatment. So I asked, “What did they do for you?” He said, “Well they gave me a heel lift.” This means they put a little insert in his shoe to elevate his heel, the goal being that the tissue affected by Achilles Tendonitis doesn’t stretch as much. A lot of what I’m trying to do with people is get to the deepest cause. What is the real source of the issue? Not just, “How can I quell symptoms?” So from my perspective, [the heel lift] is very much treating symptoms.

I asked myself, “Why isn’t it getting better? What are some of the likely causes that go into developing Achilles tendonitis?” When he first came in for an assessment I checked pretty much everything head to toe, which I do for any given person, partially just to set a baseline so that I know where any missing links are, even if I think they were not that relevant to the issue in front of me. One of the things I check is ankle dorsiflexion—how far forward can your knee go over your toes? Ideally, you can get your knees at least over your toes with your foot staying flat on the ground. He had negative degrees of dorsiflexion. [laughs] No wonder his Achilles hurt! He’s a big guy—probably 6’4”, more than 250 pounds—and he’s carrying a Steadicam, so anytime he needs to step, he’s putting a lot of strain into that Achilles. Without the ability to get your knee forward, the Achilles and tension of the lower limb are singularly shortened and tight all of the time.

Part of what can drive pain is insufficient information going to the brain. In absence of appropriate information coming from your tissues, your brain will start to send more pain signals to you, because it’s saying, “Something’s wrong here. We don’t have any feedback from this area.” So, one of the things I checked with him is called a two-point discrimination test. Two-point discrimination means you take two points of contact, fine points in this case—you can use a paperclip to do it. Fold a paperclip, then touch your skin with both ends. I want to see what he can feel as I make contact with these two points around his Achilles and his foot. He couldn’t feel much at all. This is not surprising but this is good information, because it means that part of what will get him better is anything that will help drive sensory stimulus, meaning we put different kinds of pressure and contact against the skin while he’s doing his exercises. This gets him more bang for his buck, because we’re helping light up the parts of the brain that can feel his foot and it’s going to help decrease the pain signal going to that area so that he feels like it’s safer to move. He can get through his day without suffering. You start to get a cascade effect.

At one point he was sitting on my table like me, cross legged. And I was thinking, “This is a lot of range of motion for a big guy.” Your foot is the first point of contact on every step you take, right? If your hips have excessive range of motion, and therefore are more prone to instability, then potentially what’s happening is that your foot is becoming rigid, because something in that system needs to have more tension for your brain to feel that it is safe to load [bear weight on] each foot and then the next. The ankle became stiff over time because the hip had too much motion. From a holistic perspective, one of the things we did was to work on stabilizing his hip while mobilizing his ankle. Less range of motion and/or more balanced range of motion is going to tell the brain it’s safe to release the tension you’re holding on to down there.

Filmmaker: How do you mobilize the ankle and stabilize the hip?

Cash: For someone like him who is having a fair amount of pain, and works 10 months a year as a top-notch Steadicam operator, I do a lot of isometric activities. Isometric means tissues are not changing lengths—we’re not shortening or lengthening a muscle. We’re getting into a position that’s hard to maintain, then contracting in that position without changing too much. This is important because isometric activities don’t promote as much inflammation, meaning we can do more of it and he’s going to have less pain afterward, less healing time, etc. So, we did a fair bit of isometric loading of his ankle. In terms of stabilizing his hips, that was more integrated because there are different approaches to movement out there, and I try to address how the body is working as a system. That means his rib cage is influencing his pelvis, which is influencing his femur. So, for stabilizing his hips and helping him get more range of motion, we did a lot of specific breathing exercises that would help the muscles that were holding too much tension to get off of it, and other muscles to get on tension, simultaneously. This way his brain is getting information from parts of his body that he hasn’t.

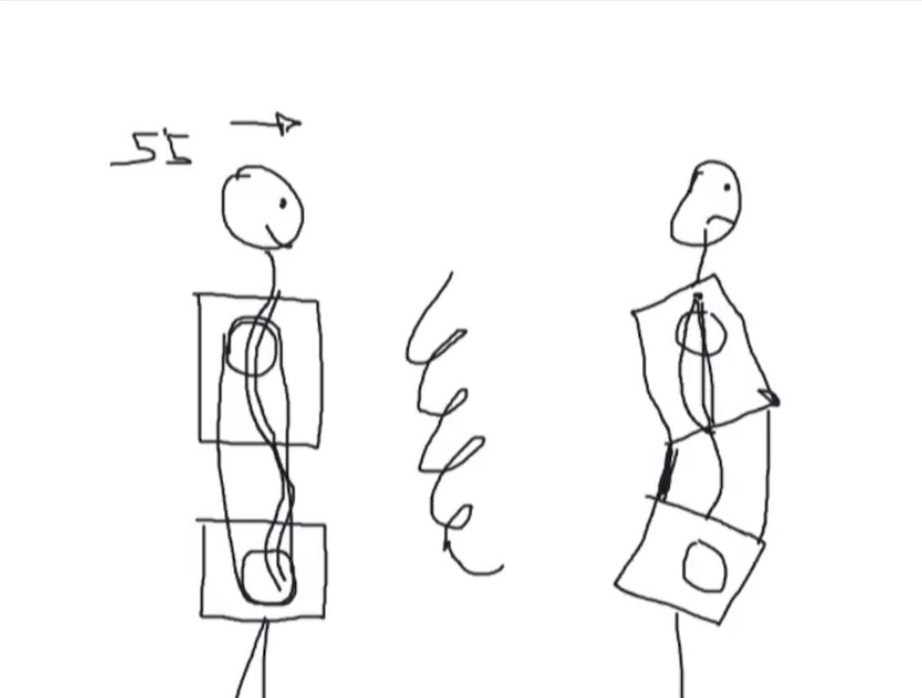

Let me do this because it’s a really useful exercise for people and one of my favorite ways to explain this: [Liz Cash draws a visual aid.] Here’s our little stick man, alright? He’s facing this way. The spine is meant to have opposing curvatures at each major juncture. The cervical spine should curve forward, the thoracic spine should curve backward, the lumbar spine should curve forward again, then the sacrum curves backward again. As a result of our ability to maintain these curvatures, the spine can be nicely decompressed, and he would gain access to a range of motion at the hips and shoulders that is optimal.

From this position, the spine almost has a spring mechanism where its ability to compress and decompress, to manage tension, is optimal. If we imagine the hips and shoulders are like a pulley system: in order for a pulley system to work, we have balanced tension on each side of that pulley. That enables those rotational points to be very efficient at pulling things up, pulling things down, doing whatever the pulley’s meant to do. The hips and shoulders work the same way: when the spine has appropriate curvatures, such that the rib cage and pelvis can be in a fairly neutral position [with the least rotational stiffness], the hips and shoulders are going to have all the range of motion they’ll need to have. For someone like him, who had an insufficient range of motion in certain directions in his hips, and tons of range of motion in other directions, his pelvis is not in this position, and this is affecting how well you’re going to recover from a hard day, how much access you have to the strength that your muscles should be able to give you. What a lot of people are doing is walking around like this: Their pelvis sort of dumps forward, and their ribs flare up. Unfortunately from this position, your lower back becomes hyperextended, and a lot of times your thoracic spine becomes flatter rather than curved like this in the first example, and the cervical spine also becomes flatter. This is not a happy place to be. [laughs] This person is going to have less range of motion at the hip and shoulder. The only way for this person to maintain this position is if the bone structures that are closer together are holding a lot of tension. Their abs are super lengthened, and they probably have a hard time feeling their abs. But I can tell you that person feels their back all day.

So, back to your question: what were we doing to help address his hip stability? Part of what we were doing was just helping to get the rib cage and pelvis more neutral. The other thing to consider with this is, let’s say the other person is 5’5”. Now the distance between their head and feet is theoretically the same in each case. But what’s happening when we lose the curvatures in this ideal spine, and this should make sense from a physics and math perspective: the only way for us to have two points of contact—one in which we have curvature, the other in which this became straightened—is that the distance here got shortened. Otherwise, it would have gone around and would be a farther distance, because the shortest way to get between any two points is a straight line. The person in this unhappy posture definitely has more likelihood of disc issues and herniations, because you’re literally taking something longer and compressing it.

Why I think this is important to understand, is that they can take the most fundamental pieces of the puzzle and start to take it into their workouts. Let’s say you’re doing an exercise in which you should feel your hamstrings. This person is going to feel their lower back when they try to use their hamstrings, because their pelvis is not in the position from which their hamstrings could easily contribute. That is a big picture, macro perspective on what a lot of people need more of, and this operator was no exception. If we can address this fundamental piece of where is your pelvis and where is your rib cage, are you neutral? That’s going to make them way more efficient on set and in their workouts without working harder. They’re gonna get more out of their efforts, burn fewer calories, and be able to have more force production without slogging through some crazy intense workout five times a week. The force a muscle generates is relative to the length of the muscle. When this is optimal, you can remove the barriers caused by poor alignment to the strength you already have.

Filmmaker: How do you know if your spine is not neutral?

Cash: It can result from all kinds of things. I sometimes joke that I blame pediatricians. Remember when you were a little kid and the doctor says to take a deep breath, and they model for you what that looks like? They extend their back to breathe in. This is exactly what you don’t want to do. That’s what happens over time, for any number of reasons—people get stuck in this extended pattern of using their spine or their neck to breathe. Now imagine someone’s in a Steadicam rig, and the weight of the rig is pulling down. It’s not visible, but if it is happening in a small way throughout the day that person is going to have back pain, because their spine is working as they breathe in. And how many times do we inhale? A lot. You’re basically loading your back on every breath in. A lot of what’s modeled out in the world in terms of what it looks like to stand up straight is actually extending the spine. Go to a gym and you can hear a trainer saying, “Chest up!” [laughs] It’s a common cue. I understand what they’re trying to correct, but it often encourages people to extend. An extended spine does not actually rotate as well as a neutral spine. So, if you’re in an extended spine and you don’t know it, because it’s just ground zero for you and you’re doing movements that require rotation, you’re more likely to be creating pathology in your tissues and/or just increasing pain overall. That does not mean you should never be extended or flexed—there’s a healthy range for these things. The main question is, can you get out of it? Can you get into an extension when it’s appropriate and get out of it when it’s not?

I have people stand up and tune into where they feel the weight in their feet, because a lot of people are forward on their toes and don’t realize it. When you start to walk around and move your center of mass over your feet, you’ll start to become more aware of where you are. If you’re extended, you’re more likely to have weight on the balls of your feet. If you feel your heels, your center of mass has to move back a little bit, so there’s a greater chance that you’re stacked as opposed to if you start to lean forward and your toes and your forefoot have to work.

The other thing that can be helpful is to look at the wear pattern on your shoes. Which part of the shoe is worn down? An indicator that someone is in extension is that the outside of their shoes is worn out and not the inside at all. This means that their feet are supinated [rolling outwardly] all the time, and they’re turned on to the outside. If you can’t pronate [rolling inward with the foot], you don’t have a neutral spine. I think a lot of people from the running world think pronation is bad, but I would be willing to bet some money that there are way more people who are underpronating than overpronating. I see excessive supination way more often than I see excessive pronation.

Filmmaker: We’ve talked about this before, but I think we should talk about just how important wearing the right shoes are in all of this.

Cash: A few years ago, I used to be a big fan of having my clients train barefoot. My thinking at the time was that more contact with the surface was going to send more information to the brain. If we were on grass or sand that might be true, because the surface of the earth is soft, and as your foot goes through the supination/pronation process it’s going to get more of the compression and decompression that occurs as the earth’s surface collapses and meets the foot more. However, on hard surfaces, your foot’s not getting that. Part of what I started embracing in 2022 was recommending shoes from this [Hruska Clinic] shoe list curated by a physical therapy group that evaluates hundreds of shoes. It was staggering to see how much faster people got better when we got them in shoes that were right for them. The brain is getting more information from the whole system because the shoe is able to meet the foot wherever it needs to be. For instance, supinators need a shoe that will help them pronate. That pronation moment is the way your brain knows that it’s time to begin to switch legs. As one foot resupinates, the other leg starts to swing forward and make contact with the ground. This is also going back to that spring loading thing that we talked about. Your foot rolls in, all these things lengthen and shorten again. This helps tissues have more of an on-off cycle, an alternating process, going to full length and re-shortening just like a spring should. This makes people way more efficient.

I have a guy I’ve been working with who’s been experiencing some pretty severe pain for two months. It’s changing the way he moves. Without realizing it, he’s leaning forward to try to get out of the positions that provoke the pain. That’s where the right footwear makes a difference, because it helps you to not compensate and better feel where you are in space, which is often on proprioception [the sense that lets us perceive the location, movement and action of parts of the body]. If you have good proprioception, you’re going to feel whether or not you’re extending your spine, or you’re rounding, or you’re on your left or right foot, instead of doing that unconsciously. Movement should be reflexive. But, as with learning many things, we have to make the unconscious conscious for a while, then it can become unconscious after a while.

One of the things I try to teach my clients—if something is working, you should feel a difference, period. Secondary, in regards to anything chiropractic or that requires manual therapy, someone needs to put their hands on you to manipulate the tissue. There’s also an important thing to be aware of, parking lot syndrome. You go to the chiropractor, they adjust you, you leave and get in your car, and your back hurts again. It’s already back by the time you’ve gotten to the parking lot. This is a sign that it didn’t really get to the underlying issue. What’s important to consider is that your brain’s first priority is to keep you alive, to keep you safe. Sometimes, when people are experiencing pain, it’s the body’s best way of protecting them in the moment. That could be pain that’s meant to get you to stop doing something, or it can be pain that’s the result of your body’s best attempt to stabilize you. Like the guy with the restricted ankles and unstable hips, that was a protective mechanism. If something’s working, if it’s what you need, you’ll feel better. Things should feel easier and more efficient. People have unfortunately somehow gotten into thinking they should trust their provider more than themself.

There’s a time and a place for things like chiropractic and massage, but a lot of people are chasing symptoms with those interventions. I have an osteopath in Brooklyn that I refer my clients to when I can tell they need manual therapy and it’s something I know that is going to be a turning point in our process. But in the long term, it’s important that your brain is re-learning the strategy it uses to get you to point A to point B. Your brain has a system that it’s developed that you’re not aware of for what muscles we fire, in what order, to get off the couch and up the stairs. Until we change the strategy by actively doing things, we are not as likely to retain a change.

I’m a big fan of acupuncture. There’s a time and a place for manual therapy and soft tissue work, and every practitioner’s going to have a slightly different perspective. In an ideal world, passive intervention should be coupled with active intervention. So, if I refer someone to my osteopath, he’s going to do hands-on stuff, they’re going to be on the table not moving. Hopefully, that helps to get them more neutral, then they come back to me and do the work to maintain that neutrality.

Filmmaker: What’s an example of passive intervention?

Cash: Like a chiropractic adjustment, meaning the client isn’t actively doing anything, their body is being moved by someone else. Massage is a passive intervention most of the time. Chiropractic is passive. Osteopathic manipulation sometimes could be active but is mostly passive.

Filmmaker: Is there a common misconception about injuries or the body that you notice your clients have?

Cash: Stretching. I always say it’s the biggest misconception. There’s a really fun way to understand a common reason that people experience tension, which people can try on their own if they want to. Try to touch your toes from standing position. Let’s say you can’t touch your toes, then you put something between your thighs and squeeze it, and while you’re squeezing this thing, you try again. Many people will see an improvement in their range of motion, and this is because they have restricted range of motion—not because their hamstrings were too tight, but because their body perceived instability and removed their access to reaching farther away from center, to reaching for the floor. If you don’t get an improvement by that, it’s still not highly likely that you need to stretch your hamstrings. [laughs] But, there could be another thing that’s causing tension in the system.

Another fun thing for people to try: Spend 60 seconds rolling the sole of your foot lightly on a ball, like a lacrosse ball. Not even hard. This is going to down-regulate tension, again protective tension potentially, and you can see an improvement and be able to touch your toes. This is important because people are spending so much time trying to become more flexible. Not that many people need the flexibility they think they do. Once you’re aware that sometimes tension is protective in nature, then the answer isn’t just how do we get rid of this tension: “Should I stretch? Should I foam roll?” The question is, “Why is this there? What was missing that my body decided it needed to come in and tense everything up to protect me?”

Filmmaker: How can you evaluate whether you’ve hit a limit or point of diminishing returns with stretching?

Cash: If you lay on your back, let’s say you hook a belt around one leg and pull your leg straight into the air. All you need from a healthy hamstring extensibility perspective is 90 degrees. So if you’re on your back, lift your leg and get to 90 degrees: good! You don’t need to stretch. I also think people don’t understand the purpose of stretching. I often get the question, “Should I stretch if I’m sore?” Soreness is the result of tissue being torn as we demand more from it. That means you need to promote circulation by walking, doing gentle activities to get the blood pumping and get appropriate calories so that your body has the resources it needs to help that tissue heal—having important vitamins and minerals in your body. Stretching is not doing a lot to help those tissues repair.

Because people in the movie business have such crazy schedules, my perspective is: What are things that they can know and have access to that are going to enable them to give them the biggest result in the least amount of time? Because I want people to get home and be asleep as fast as possible after work. I don’t want you going to the gym for an hour and a half because you think that’s going to help you more than rest.

Filmmaker: How do you recommend we hydrate?

Cash: Ideally, you’re getting half of your body weight in ounces of water per day. If you’re 120 lbs that means 60 ounces, etc. If for whatever reason that’s hard to do, the other thing that I think is really important is that your water has electrolytes. Some people drink a ton of water, and if you overly hydrate, you’re going to be flushing out electrolytes—and those are really important to how well your muscles and tissues function. I like to use a product called Trace Minerals. It’s very potent; it does not taste good. [laughs] They have it in liquid form and capsule. I put a little in my water every morning. I have had clients who were struggling with muscle cramps and things like that see noticeable improvement by adding Trace Minerals. I usually tell my clients who work a lot to put it in their set bag and keep it on the cart. In the hierarchy of things your body needs, hydration is way up there.

From a nutrition standpoint, it’s important that you’re dialing in on the kinds of food that give you sustained energy, rather than sugary things or other things that will likely make you spike and crash. Physiologically speaking, fat and protein will give you more sustained energy, and contrary to what a lot of people assume, carbohydrates in the evening can be useful because they are going to crash you a little bit—you’ll sleep better!

Filmmaker: Tips when alternating between day shoots and overnights?

Cash: From a circadian rhythm standpoint, some things begin at home. Ideally, your bedroom is pitch black at night. Whenever you’re sleeping, you don’t want any light in the room, no alarm clock shining on your face. You want it to be dark and relatively cool, ideally 65 degrees. Obviously, you need to dial in to your own comfort level. Those two things will make a difference in your sleep quality. Ideally, you don’t eat within two hours of any time you’re going to sleep, which is hard, because as people’s circadian rhythms get crazier they start craving weird food.

People in the movie business have a shifting sleep-wake cycle that is akin to having constant jet lag. One thing you can do to help regulate jet lag is take a cold shower whenever you get up and a hot shower before bed. This is going to shift your internal temperature, and that’s part of what tells your body what it should be doing at what time of day.

Filmmaker: What are the most common problems or injuries you see in clients?

Cash: Back pain is probably the highest on the list. After that, neck and shoulder stuff. Camera people’s shoulders get compressed often—I realize not everyone’s doing handheld all the time but that one’s up there. Knee pain. Foot issues are less common. Back stuff, hip, shoulders, neck. I had a DP who was struggling with elbow and wrist pain, which was tricky because he was doing a lot of documentaries where there was a lot of handheld. At some point, we determined that his phone use was really driving the wrist stuff.

Something that has been useful to quickly tune in to what’s going on with someone is to see their operating position. They send me videos of themselves on set. I had a guy once who had his camera with him, and he puts the camera up and shows me what his operating position is like, and it’s like, “No wonder your neck hurts! That head position is not good!” How are you stacking yourself when you’re under the load of the camera? We can quickly change that right away: Let’s bring the monitor closer, bring the rods farther out, whatever quick adjustments we can make to the camera and how they’re holding it.

One of my Steadicam operators sent me some videos of himself in the rig and he was shrugging his shoulders all the time without realizing it. Just that one thing has several potential carryovers. If people are having acute or chronic issues, I recommend starting with eight sessions, then depending on their availability we do eight sessions in four weeks, or maybe eight sessions in eight weeks. Everyone’s trajectory is different. Some people are going to take a little longer to learn and retain what their body’s doing, other people are dramatically better within two or three sessions. If you don’t have acute pain, I really don’t need to see you one-on-one. At that point, I transition people into my remote coaching program, which is called Strength Squad. I still monitor them, they still get some one-on-one but do their workouts on their own. Once you’re no longer in pain, I can still monitor your workouts, make sure you’re not doing too much and doing the things that really matter, and make sure you’re now on the trajectory to being totally independent.

Strength Squad is the latest iteration of different virtual models I’ve tried with people, and so far it is by far the best one. Part of what I realized over the course of pandemic is that people really need accountability. If I had to put a percentage on clients who can do things on their own and will do them, it’s like 10%. Strength Squad is a six-month coaching program. It was originally three months, but what I saw was people who are four weeks in would get a job that’s four months long, start to fall off the wagon and just give up. Part of what we’re trying to do is help people find out what their sticking points are—when life gets hard and work is 15 hours a day, what are the most important things that you could still be doing that will keep you inching forward in the right direction? Over the course of six months we inevitably get into one of those sticking points and get out of it again.

For some people, it’s nutrition. They’re going to start feeling like crap because they’re eating like crap, and it might not be as important for those people at that point to be spending time working out. For other people, it’s about figuring out how to do more with less, to actually come to terms with the fact that doing something 15 minutes a day every day is going to get you more time during the course of the week than one 60-minute workout on the weekend. It’s not all about becoming stronger; it’s about becoming more confident, less afraid, when you realize you can trust your body to give you the feedback you need to make the changes you need to make, and that you know that change is possible. That’s so empowering for people to realize—your body can change and you can make that happen. The choices you make can change your outcomes.

Filmmaker: How can we better standardize such education/practices for better health on set?

Cash: I think it would be great if people in all unions, or any sort of craft that requires physical labor, were offered some sort of training. Maybe it should be more elective than compulsory. There could be tiers of training that are available: safe lifting fundamentals, injury prevention skills, so on and so forth. If there was a way for the movie business to incentivize people to take that training, maybe you take that training and they decide you get 100 hours knocked off of your requirement to qualify for the MPIHP [Motion Picture Industry Pension & Health Plans].

So many people come to me, especially with their handheld position, and I go, “Oh my god. The physics of this are terrible. No one would survive this.” This is so avoidable. At this point I’m just trying to continue to do what I do and hope other organizations find out about it and seek collaboration as it’s possible.

I’m doing a research study for Steadicam operators, because one of the things that’s been fascinating since I started working more with them in 2019, is to hear them make very strong statements about how this vest is the best one and saved their career and that vest almost ended their career. Then someone else says the opposite thing. We need to know what is the body type that works well for this one and that one. So last year, I began an open study and invited people to participate. People all around the world signed up. I’m just trying to assess enough Steadicam operators that I can identify what the underlying factors are, so that we can say, “Here, do this ten-minute assessment. By the end, it will tell you what vest will be best for you.”

Filmmaker: In my interviews with DPs and cam ops, a lot of them had seen colleagues who retired due to longterm damage to the body. Is this something you’ve seen?

Cash: Many years ago I heard from a number of camera people, operators in particular, about really bad injuries. I thought, “Wow, that’s a lot of people who have nerve damage, herniated discs—significant problems.” It’s possible that they had a herniated disc anyways, had posture issues a long time ago, and the camera world just put them over the edge. Regardless, part of what people are up against is the fact that a disregulated sleep cycle is stacking all the chips against you. A regular sleep cycle is one of the easiest ways to get your body more parasympathetic and into the states where healing happens. So, just by having that disregulated sleep cycle you have an uphill battle. One of the things I’ve begun to suspect is that people who seem less affected by the business is the small percentage of the population that genetically tolerates six hours of sleep or less well. But if sleep really quickly affects your mood and emotion regulation, movies is gonna be a hard life.

Filmmaker: What are some of the quick on-set exercises that you teach clients?

Cash: I give them very specific drills, based on the asymmetries that we have identified, that give their body and brain a chance to get out of that pattern into another one that allows them to get more neutral. It is so important that people are able to get out of extension and into a neutral spine. When you’re stuck in one pattern all the time—and a lot of people are—your brain is literally getting less information all the time. This is going to make it harder to sleep, give you more pain, less strength, tip the scales on the continuum between parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system—meaning fight or flight, rest and digest. It’s tipping them towards becoming more and more sympathetic, more and more fight or flight. I’m trying to give them something that they can do for 60 seconds to two minutes to quickly get them back in the center again, and oscillate between these two ends of the spectrum. That’s not solving all their problems, but I want to give them resources to keep them out of the red zone, and when we have more time we can focus on the rest. The real name of the game for me is: Give them the drills that will keep them out of compensation when one injury leads to another.