Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Didn’t Want an Audience Member To Be Able To Say, ‘Oh, That Was Just One Bad Cop’”: Stanley Nelson and Valerie Scoon on Sound of the Police

Sound of the Police

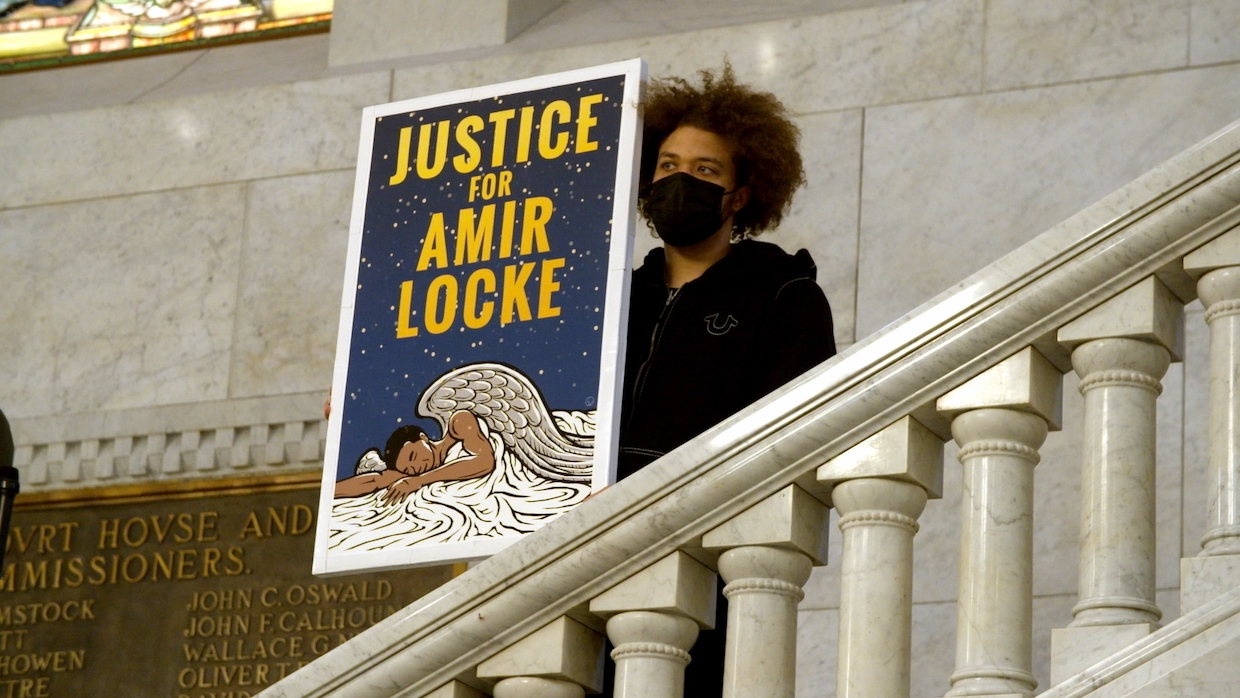

Sound of the Police Stanley Nelson and Valerie Scoon’s Sound of the Police is an exhaustive exploration of the oppositional dynamics between African Americans and law enforcement, from slavery right up to today.

Through a wealth of archival imagery, interviews with academics, authors and assorted deep thinkers of various backgrounds and colors as well as an ear-catching soundtrack (indeed the doc’s title is a nod to rapper KRS-One’s 1993 anti-police brutality anthem “Sound of da Police,” which serves as a sort of sonic exclamation point throughout the ABC News Studios doc), the veteran filmmakers make a compelling case that any relationship built on the racist foundation of the slave patrol is one systemically doomed from the beginning. Which, of course, demands nothing less than a new start. (Let the reimagining begin!)

Just prior to the film’s August 11 Hulu debut, Filmmaker checked in with the busy Oscar-nominated, Emmy Award-winning MacArthur Fellow and his producer-director-FSU professor collaborator (who’s also a former executive at Oprah’s Harpo Films).

Filmmaker: How did this project originate? You’re both accomplished director-producers in your own right, so why decide to team up for this specific doc?

Nelson: I originally pitched this film to Jackie Glover, who was then at ABC News Studios, who I’ve known for a long time. I had wanted to make a film about policing for many years, so I was glad when she said she was onboard.

With my production company Firelight Films I have a lot of things going on, so I knew this film would be much better if I could find a talented filmmaker to collaborate on it with me. I’m grateful to have been introduced to Valerie. This is not a simple story to tell. I needed somebody who could pay attention to detail day to day, which Valerie was able to do.

Filmmaker: How exactly did you divide up directing duties? Did you both participate in every facet of production, from the interviews, to the archival research, to the soundtrack?

Nelson: Valerie performed 95% of the interviews, though we collaborated on the questions for each of them. And then I gave continuous notes through the rough cut, at which point I assumed a larger role in finishing the film.

We focused on gathering archival footage from the very beginning because it was essential to this film that we had a wealth of archival material to construct the story around. We made a decision early on that we wanted multiple examples of every kind of police interaction that we document in the film because we didn’t want an audience member to be able to say, “Oh, that was just one bad cop” or, “That one cop just had a bad day.” When you see footage of police officers wrestling Black children to the ground over and over again, or handcuffing a little Black girl because she acted up in school, you can’t deny that there’s a problem.

For the soundtrack I was excited to collaborate again with Tom Phillips, with whom I’ve worked on maybe 8 films, including Attica. We work together really well. Tom’s specialty is movie music, so he doesn’t get thrown by you saying something like, “I think the music is too fast here” or “No, that music is too dark.” He’s not going to say, “What do you mean by too dark?” because he intuitively understands; he knows that filmmakers and musicians use different language to describe similar things.

Filmmaker: How did you select your interviewees? Were there any folks you reached out to, and especially hoped would participate, that ultimately declined?

Scoon: I started by researching and reading books because we first wanted to engage with people who have thought deeply about this topic, and those people tend to be historians and scholars. And because of Stanley’s long history of documentary filmmaking he has great contacts like Al Sharpton and Ben Crump, who’ve made civil rights issues their life’s work. Besides those thought leaders we wanted to engage with people who’ve experienced policing firsthand, whether it be victims of police brutality and their families or members of law enforcement.

Nelson: With all of my films I ensure that interviews feature women and men, Black and white people, and a diversity of perspectives so we can tell the whole story.

Scoon: I’m pleased to say that probably 98% of the people we contacted about participating in this film responded favorably. In fact, I pre-interviewed maybe 20 people who we didn’t end up going back to for the film because we already had so much material.

Filmmaker: Watching this historically jam-packed doc also made me wonder if you might have enough material for a series. So what aspects of this story, perhaps due to the time constraints of TV, were left on the cutting room floor?

Nelson: One thing I’ve noticed about myself is that once material is on the cutting room floor, and once the film is done, I don’t think about it anymore. We spend a lot of time in the editing room and everything is carefully considered, so when something is cut, it’s cut for a good reason. I’d go crazy if I second-guessed myself on that front.

Scoon: I agree with Stanley; and I tell my students that if your movie can function just fine without that scene, then you don’t need it. With Sound of the Police each section of the film could be a documentary in and of itself, but ultimately everything has to be proportional, so that sense of proportionality helps guide the edit.

Filmmaker: What are your ultimate hopes for the doc? Are there any audiences in particular that you’re intent on reaching?

Nelson: I’ve never made a film where I thought that it was supposed to do any one thing for the audience. I hope people will better understand the relationship between the African American community and the police. And I hope that people are moved to push for some kind of police reform, some kind of change in the way that the police operate. I think responses to this film will be unique from responses to the other films that I’ve worked on because I think that every aspect of a person’s identity—their race, age, gender—significantly colors how they perceive and interact with police.

Scoon: This film is for anybody who wants to see our country be better. I hope people who see it will think about how to improve the system of policing, and how to improve communication between police and the communities they are meant to serve.