Back to selection

Back to selection

AI Is Already Changing Filmmaking: How Filmmakers Are Using These New Tools in Production and Post

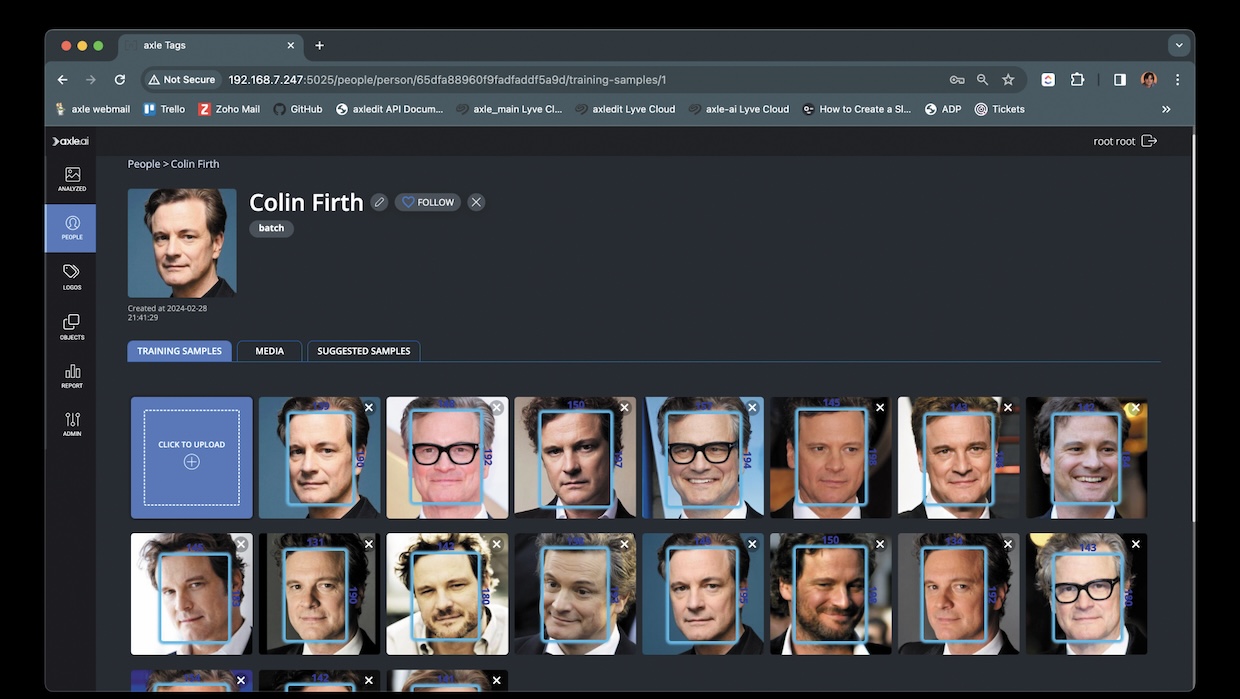

Axle's AI platform in action

Axle's AI platform in action When Sora, OpenAI’s video generator model, hit the internet in February, realistic-looking demo videos flooded social media, usually accompanied by some form of “RIP Hollywood” commentary. While Sora still isn’t publicly available, between Runway, Pika and a slew of other video and image generators there have been many questions about what the future of filmmaking will look like—and whether humans will even be the ones making movies in the future.

Right now, generative AI is still far away from creating consistent characters and the exact, carefully crafted images that industry professionals require. Maybe a movie will be entirely generated with AI in the future, maybe not. However, artificial intelligence in filmmaking isn’t new; it’s been in some mainstream editing tools for nearly 20 years. Beyond generative AI hype, there are many AI developments that will have a much more immediate (and useful) impact on the way we make movies. How might we use AI to edit and sort our footage faster? Are we going to be using different AI models for different tasks like we do with plugins? What about completely relighting a subject in a new environment with the click of a button?

Filmmaker looked at a variety of new tools across all stages of filmmaking and talked to many new companies at this past April’s National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) show about utility AI—functional, useful, assistive AI that will help us make better movies faster and for less money.

AI: It’s Already in Our Edit Tools

AI has already been inside editing tools or non-linear editors (NLEs), it’s just gone by other names—machine learning, neural engine—or none, just a simple magic wand icon.

Avid introduced ScriptSync in 2007 and PhraseFind in 2011, enabling editors to synchronize footage with scripts and search for words or phrases within their clips. Apple’s Final Cut Pro X, released in 2011, used AI for tasks like auto color balance and classifying shot types. More recently, it added background noise removal. In 2019, Blackmagic introduced its Neural Engine, which enabled tools like facial recognition and speed warp and later added voice isolation and image noise reduction. It can also analyze faces and tag your media with who’s inside each clip. Recently, Adobe incorporated its AI-powered audio tool Enhance Speech into Premiere Pro and added automatic audio tagging to classify whether an audio file is dialogue, music or a sound effect. We’ve also seen transcription tools (powered by AI) and text-based editing built into DaVinci Resolve and Premiere Pro. Plus, let’s not forget magic masking or some variation of that name, which uses AI to automatically track people or objects and create masks for background replacement or layering—basically, automatic rotoscoping.

We can categorize these tools within a few buckets that AI has been really good at: transcribing, rotoscoping and audio/image enhancement. Do these tools perform as well as a human? No. But for most tasks, they are good enough to get you 90 percent of the way through the job and save valuable time.

However, all of these features just mentioned live inside editing tools, and every editing tool has different features. If you’re editing in a program—say, Final Cut Pro—that doesn’t have AI denoising like DaVinci Resolve, you’ll find yourself doing a lot of roundtripping of your footage to another program, like Topaz AI, to denoise or upscale some archival footage, then sending it back to your editing program. And if someone who isn’t the editor—say, a producer—wants to scan through footage to find a shot or look at the transcript of an interview, they’ll have to know how to navigate the NLE.

What if AI makes us rethink what editing looks like and how the media we shoot is processed?

Moving AI Out of the Editing Apps

Michael Cioni, co-founder and CEO of the startup Strada, has a different view of how post-workflows should change to accommodate new AI tools.

“I understand how much value there is in transcribing in an NLE, but I think the NLE is the wrong place to transcribe,” Michael told me on the VP Land podcast. “I don’t think it’s fair to dump transcription on the cutting room because they have other problems there. They need to be cutting, not transcribing.”

Cioni is no stranger to redefining media workflows—he was previously Adobe’s senior director of global innovation and helped develop Frame.io’s Camera to Cloud integration. At NAB in 2023, he gave a bullish interview on generative AI, saying that “the percentage of images that are photographed or recorded in the world for production is going to go down.”

Since that interview and after more research, Cioni said that fully generated images are further off than he initially thought due to a lack of character consistency and control. He realized instead that utility AI is going have greater impact on filmmakers in the future. In summer 2023, he left Adobe and started Strada with his brother, Peter Cioni.

Cioni explained Strada’s approach: “Strada is a cloud workflow platform that’s powered by AI. We’re using AI to do the mundane tasks like syncing, sorting, searching, transcoding, transcribing, analyzing and translating. That’s where I think the best parts for creative people are: [using AI] to automate

the boring stuff so that we can do the creative stuff faster.”

Strada’s first phase focuses on simple tasks like transcribing and tagging, but Cioni outlined a vision of building an AI marketplace where custom models can be listed and used at will to process footage before it even gets to the editor, like automatically removing a logo or removing specific sounds, such as street traffic.

Another platform taking a similar approach is Axle AI. “It catalogs the material; then, it feeds them into our AI engines that do things like face recognition, scene understanding, object and logo recognition, transcription. Then, it puts all that in a big database that you can search,” explained CEO Sam Bogoch.

Axle AI’s platform is designed to be extensible, allowing users to integrate custom AI models for specific tasks. “AI is evolving so rapidly,” Bogoch elaborated. “We don’t claim to have all the answers, but we believe that with an open approach our customers can get the best value over time.”

By moving AI tasks to the moment right after recording instead of treating the technology like a finishing plugin, these platforms aim to streamline the workflow and enable collaboration among everyone in the post-production process, not just the editor.

Will AI Models Be the New Film Stock?

In an AI future, understanding what a model is good at (and not good at) will be similar to understanding when a camera sensor or film stock will or won’t work for a certain scene.

The most famous model is from OpenAI, the recently released GPT-4o. To drastically simplify things: It and other large language models (LLMs), like Anthropic’s Claude, are trained by throwing lots and lots of data at them. The problem with these LLMs when it comes to video tasks is that they’re not really trained on video. For instance, give ChatGPT a transcript of your YouTube podcast and ask it to identify a soundbite that would make a good viral short. It’ll just guess, based on the transcript, what might be a good moment, and might even make up a quote that no one actually said!

Even though these models were trained on podcasts and YouTube videos, they were just trained on the transcript of those videos and thus missed out on the visual nuance necessary for understanding text delivered in the form of the moving image. So, we’ll need more models specifically trained on video that will be better suited for media creation needs.

Train a model on the more specific type of use case you need, and you tend to get better outputs. Going back to the “identify a short clip” example above, Opus Clip is one company that did this. Conor Eliot, head of creator partnerships at Opus Clip, explained, “We built a model off of reviewing over five million different shorts that were out there on the internet. We also hired professional short-form editors to go out there and clip things well and then clip things badly and try to trick the AI in different ways. Over time, the AI got really clever and good at judging what is a good short-form clip and what is a bad short-form clip.”

What about being able to search through your footage based on the context or emotion of what’s happening? Imaginario and Twelve Labs are two companies that are training their own models for this type of use.

Soyoung Lee, co-founder of Twelve Labs, described the challenge: “It’s interesting because, in terms of the AI world, video has been neglected. Because it’s so difficult to understand video data, it would be kind of misrepresented as an image or text problem. We wanted to build, from inception, large models that are born to understand video data. And just like humans, if you can understand the world around you and hear and have that perception and understanding, that means it scales to any other modality as well.”

Twelve Labs isn’t looking to build a media management platform—it wants to be the model that plugs into other platforms to help you analyze and search your media.

Understanding what models exist, and what they are and are not good at, will be key to speeding up and improving workflows. If you’re working on a project with a lot of material, maybe you need to make sure something like the Twelve Labs model is integrated into your post system to help sort and search material. If you have a lot of sports footage, maybe you need a model trained on just finding goals; if you have a lot of archival material, maybe you need a model trained at uprezing VHS recordings.

Adobe offered a peek at what this might look like in the generative AI space. In a demo video for what the company is calling an “early exploration,” there is a dropdown selector within Adobe Premiere that allows you to choose a specific model to generate a video: Firefly, Runway, Pika or Sora.

Knowing which model is right for the task at hand is going to be key in the future.

Beyond Software: AI Inside Cameras, Sets and Lighting

We’ve covered a lot of cases of AI use in post-production, but that doesn’t mean utility AI won’t be used in production itself. A variety of use cases were demonstrated at NAB.

DJI released the Focus Pro, which turns any lens into an autofocus system. Using Lidar and AI, it can quickly track and lock onto a variety of people and subjects to stay focused on. We also saw AI inside cameras. Blackmagic’s URSA Cine 12K camera, for example, features an AI-powered lens calibration system. This enables the reading of focus and aperture data off older lenses that may not have metadata outputs.

AI has also found its way into set design and backdrops, especially with virtual production. Cuebric has been a leader in generating 2.5D (or what it now calls 2.75D) virtual sets from AI prompts. It has also developed its own models based on different genres (standard, sci-fi, film noir, etc.). And while filmmakers may be familiar with building virtual environments inside Unreal Engine, new tools like MOD Labs will use AI to analyze scenes, optimize them for better performance and flag any potential issues.

And for performance capture, tools like Move AI enable motion capture without the spandex suit—all you need is an iPhone. Wonder Dynamics, recently acquired by Autodesk, tracks and replaces a person inside your existing footage with a computer-generated character—something that would previously take an immense amount of time for a team of visual effects artists.

What if we didn’t have to light a scene on set but could do it all in post? That’s the potential future SwitchLight Studio is creating. In one of the most impressive demos at the show, Beeble CEO and co-founder Hoon Kim demonstrated how, with his company’s product, you can take any shot and instantly relight it based on the environment of a new background or by adding virtual lights. “What we’re doing is actually something called de-rendering,” explained Hoon. “We’re trying to extract all the information from 2D footage so that we can replicate the actor inside a 3D rendering engine.” The implications are far-reaching, from how we light a scene (Hoon said this works best with soft, white light) to potentially replacing LED environments.

In another demo from SwitchLight, reflections from a driving plate were instantly mapped to a car process shot using SwitchLight—a task that would normally be done in an LED volume or with extensive VFX work and 3D models. “What we’re trying to do is not like text to video,” said Hoon. “Artists want to pick up their camera, shoot and then maybe improve it a little bit or change the background. What we’re doing is kind of enabling the LED virtual production that only the super-expensive-budget guys had, like The Mandalorian—[making it] so easy for someone to change the lighting, change the environment and create very amazing storytelling content. That’s our goal.”

From Celluloid to Digital to AI?

As we talked to various companies about AI, two common themes emerged: AI is going to democratize filmmaking (i.e., make things less expensive), and what would maybe take a team of 10 to do now might take one person.

But if one person is doing the work of 10, will there be fewer jobs in an AI future? Maybe. But can this be blamed all on AI, or is this just another technology shift, like the ones that have happened in the film industry every 20 years or so?

Noah Kadner, virtual production editor of American Cinematographer, sees AI as just another tool. “A lot of people have the fear that AI is gonna steal their job, or it’s going to somehow make them redundant,” he said. “But what I’m seeing is, it’s ultimately becoming one more tool in the toolbox, and [people who] leverage it well are going to do very well in the biz.”

Stop-motion to computer animation, Steenbecks to computer-based NLEs, celluloid to digital—new tools, same destination.

As VFX legend Robert Legato, ASC, told us after his talk on AI at Vū’s Virtually Everything summit, “You go to the movies to see something you haven’t seen before; otherwise, you’re seeing a retread. It’s the thought in their head of what that shot is. The tool only helps you realize your vision; it doesn’t create it for you.”

We’re a far way away—if we can ever get there—from a magic button that creates a final pixel shot. Even if there will be an audience that will enjoy a fully generated movie, there will always be a place for human-created stories and films.

The real application of AI is as a tool—a 10x or 100x tool on what was possible before.

The question isn’t when AI is going to change the future—it’s here now. How are you going to harness it?