Back to selection

Back to selection

PAST TENSE

Winner of the Palme d’Or at this past year’s Cannes Film Festival, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is an enlightening journey graced with a fairytale feel that’s unlike anything you’ll see in theaters this year.

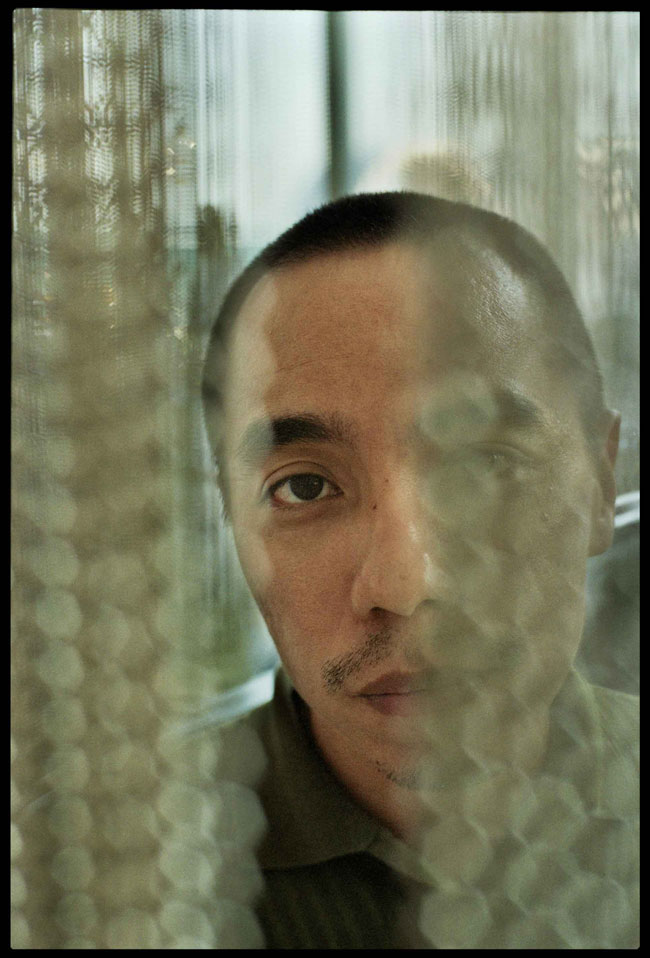

In a world of increasingly globalized cinema — misguided attempts to opt for the universal to the detriment of the texture and truth of the local — with its difficult funding environment, especially for auteurist projects, Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, aka Joe (he studied film in the U.S. so is perfectly bilingual), has become something of a one-man band. An openly gay man of 40, he makes the films (and major installations) he wants to make, mostly in his native Northeast Thailand, an area fairly provincial and covered by jungle, in the form he sees fit, using mostly the same nonprofessional performers.

A seductive oneiric feel oozes from the films — among them the features Blissfully Yours, Tropical Malady, The Adventure of Iron Pussy, Mysterious Object at Noon, and Syndromes and a Century — but it grows organically out of the material, which, for non-Thais, seems to frequently border on the irrational. That which might appear “ordinary” becomes singled out for a recognition that takes on supernatural significance. This is Weerasethakul’s world, a perfectly balanced mélange of real people, intense encounters, political references, and ghosts and reincarnations, none of them casually addressed.

The plot of Weerasethakul’s most recent film, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, which took the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, is relatively straightforward, if also deceptively dense. Uncle Boonmee is a member of something akin to the rural gentry. He is dying of a kidney disease (as did Weerasethakul’s own father; much of his work is autobiographical, and medical issues and disease are major themes, perhaps not surprisingly for the son of two physicians), and, through its editing, the film turns into something of a survey of his past incarnations.

It is not always easy for the viewer: Is the water buffalo shown at the beginning of the film one of Uncle Boonmee’s past lives? As is the catfish who services a disfigured princess in a lake? Ghosts appear at dinner, almost as expected guests: Uncle Boonmee’s late wife, and, in a cheap gorilla costume with blazing red eyes inspired by classic Thai TV and films, his long-lost son. All of this is presented as normal; no one is shocked by the resurfacing of these characters. Ultimately Uncle Boonmee leads his entourage to a cave for his final farewell; this is the site where some of his earlier incarnations may have begun their earthly existence.

TIFF Cinematheque’s scholarly James Quandt, a frequent contributor to Artforum, has edited an excellent volume on Weerasethakul’s work entitled Apichatpong Weerasethakul, which is published by the Osterreichisches Filmmuseum in Vienna. Quandt is the foremost expert on Weerasethakul’s work, so I shall take the liberty of quoting from his introductory essay before moving into the two interviews that took place between Weerasethakul and I this past fall in New York.

…Weerasethakul’s modus [is] to turn everyday objects and images into the ineffable and enigmatic, inhabitants of a phantom zone where the hard, ‘real’ world of cars and bodies and buildings cedes dominion to a magical landscape of desire and reverie….Time becomes suspended and setting ebbs from actual into dreamscape….Uncontrived, intuitive mystery, a rare commodity in any art, abounds in Apichatpong’s cinema. He can’t seem to cast his eye on any object without making it strange, not so much defamiliarized as ineffable. One surrenders, blissfully, to that strangeness.

Strand Releasing opens Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives in March.

You live in Chiang Mai, Thailand? Yes. I go back and forth to Bangkok a lot because everything is in Bangkok: [my editor] Lee, my family, the facilities.

And Uncle Boonmee is set in Northeast Thailand? Yes. The installation [version] was done in 2009. Uncle Boonmee is the last chapter of the project, so now I want to move on.

But first you did a short on the subject? Yes, that’s part of the project, a short film.

Tell me about your installations. Are they mostly projected media? Yes, two big spaces. One is with six screens, the other has a synchronized cinema.

How do the installations relate to the films? In the past they were quite separate. They were more like sketches. But lately they are more integrated into my films. The idea of memory: the installation work allows more experimentation in a shorter format. The feature film of Uncle Boonmee has become part of this project that has installations: a feature film, photographs, a book — all these things.

Did you start with films, installations or video? You went to the School of Art Institute of Chicago, right? I studied architecture in Thailand. I never practiced; I did kind of an internship. I designed a mountain in front of a hotel. [laughs] That’s all. I always wanted to make films, but I didn’t know what kind of films. I studied film for a master’s degree. Architecture was like a cushion: If I didn’t succeed [as a filmmaker], it was something I could fall back on. Twenty years ago in Thailand film was not a career. When I came to Chicago it was a shock because I was from a small town, I didn’t grow up in Bangkok. Chicago was such a diverse city, and it had such diverse, experimental cinema. Even things you do by yourself like painting or sculpture could be called cinema, private activity. That’s why I’m hooked.

Has your architectural background influenced your vision in film? Eisenstein, Dmy tryk, Lang, they all came from architecture or engineering. Wow. I think so. I think that the time element in architecture and film is shared. You decide the angles, the openings, the relationship of time to space, the light.

Let’s address the concept of reincarnation and transmigration. It’s not completely divorced from your culture. It’s not too farfetched to say this is another reality because the reality now has changed from when I grew up. The media has changed, the landscape has very rapidly changed in my town. Also the way we make films, even though the contents are very local — ghost stories or whatever [laughs] — utilizes a very standard, Hollywood-like vocabulary. So I felt like I wanted to make Uncle Boonmee as a remembrance and tribute to all those films that I grew up with, the ghosts and the invisible, the human world, and all in between. All these things had expression in the past but not now. In Thailand we believe, of course, in ghosts. In the media it’s treated differently, with a lot of digital effects. Sometimes I feel not into this.

You present possible earlier lives of Uncle Boonmee, like the buffalo, but they are not spelled out. I feel like I wanted to open with nature. The movie goes from the color green to gold, then [goes] back to nature again. I start with a monkey looking at you, the same way in Tropical Malady: the way the soldier looks at the audience when the credits come up. It’s like dividing the audience: “You are going to see a fiction, illusion.”

Do you use CGI? Yes, a lot. But somehow it supports the movie. It has to be integrated, like in Tropical Malady. That’s CGI, but it’s not superimposed on it.

How did you get the fish to make love to the princess in the lake? Animatronics. A very simple one with a rubber fish. Someone nearby is doing a puppet kind of thing.

You said in interviews you bring a lot of your personal life into your films. Your own father died of kidney failure. When I try to make movies with stories, especially with Uncle Boonmee, the subject was someone else. The fact that I didn’t have enough information about him forced me to approach the movie in a different way. The most comfortable way is to put myself, what I know, my memory and the architecture into the story.

So Uncle Boonmee is an homage to classic Thai cinema? It’s not from any specific movie. It’s mostly low-budget movies and from television, especially when the programs were shot on 16mm in the studios. That’s why the style is quite different in the dinner scene and in the outdoor scenes.

You seem to favor certain strategies like long takes and shot/reverse shots that are not 180 degrees. Is there an ideological component attached to the way you make these decisions? Or do they just feel right? There must be some rules that I force myself to use, but I never write them down. In Blissfully Yours in 2002 I used rigid rules: everything once, a single dolly shot, very conceptual. But [this time] I found myself more spontaneous. The rules sometimes don’t apply.

How did you get the ghostly effects? The ghost effects are in camera. Large glass — we could have done it with computer graphics, even cheaper with a blue screen. To have a glass and to spend time on the lighting stuff was more expensive, but I really had to insist we do it like this. We really had to evoke this old style.

How did you use the glass? This is a chair, this is the glass, and the camera is here. [He points at the chair.] So you put the actress here, the camera shoots through the glass and you turn up the light, so her reflection appears on the glass. The camera captures her transparency, and my transparency, appearing on the chair. It’s a very old-style Hollywood technique.

You usually shoot in Northeast Thailand, near where you grew up. What is the size of your crew, and what are the shooting conditions? The crew is 20–30 people. Sometimes when we have a lighting crew or extras, it can be 100 or more. Those are the scenes I end up cutting out of the movie. [laughs] My art director always asks whenever there is going to be a big scene, “Is this going to be in your movie?” [laughs] And he’s right. That’s the nice thing about not editing my film, I feel too attached.

Those kind of things end up on the cutting room floor? Yeah, but I hope they will be on the DVD. [laughs]

In Uncle Boonmee, what did you cut out? Mostly I cut a lot of the princess scenes, like when she is with the villagers, the costumes on the villagers. It’s too much like other films. Even though I want to pay tribute to [these other films], it’s already enough.

Are all the buildings in your films locations, or do you sometimes build? Like in Syndromes and a Century, the wonderful house of the orchid grower? We built that house. We traveled along the Mekong River and took a lot of pictures of houses. So I chose the corridor here, the window here, this color, then we constructed the house, except for the concrete part, the cellar.

There always seems to be in your films illegal immigrants from neighboring countries. You refer to their troubles, prejudice, lower wages. That’s an issue in Thailand. You had lots of people coming from Burma, from Laos, and from Cambodia in the ’90s. I’m whiter skinned because my grandfather is Chinese, from China. People from China really work very hard. It was hard because it was not their land. Originally in Northeast Thailand were the Khmer, the root of Cambodia, darker skinned. They entered agricultural careers. Do people in commerce or with better education tend to look down on people with darker skin? I want to present this, but not directly, more to show how people treat one another.

The area where Uncle Boonmee is shot is fairly isolated. You deal with topics like the supernatural and agriculture, then suddenly you have stills evoking the political situation. That’s from the installation actually, in which I worked with the teenagers in the village. Communism spread to this village. This is the “Primitive” project. I wanted to use my memory. It was my actual dream. I dreamt about this picture while I was making the installation. So I wrote the script while I was making the installation and also recycled it in the feature film. It’s about the recycling, reincarnation of the script, and also my memory of this teenager that I worked with in the region. It also refers back to the cinema when you talk about the future, but what you see is something like pictures of Christmas, say, when the image hasn’t moved yet.

In your post-Cannes year, have you started on a new project, or are you following up with publicity for Uncle Boonmee? I am trying to write now, to make something about the Mekong River again, the same area, about the flooding and also the drought that affected many lives there, and about the epidemic disease of the livestock as well.

Will this be a narrative? There is no story yet. I need to go there and see people and then write.

What about gay subjects? Tropical Malady was maybe the first film with a gay character. But after making it, I don’t feel like it’s a gay film. Like in Syndromes and a Century, I don’t want to underline these sexual issues. I have an issue myself, like with gay parades. I find it strange to announce these things. In Tropical Malady, the characters were presented with such a utopian viewpoint. Everyone accepted their love. In reality, it’s not like that. In Thailand, you have transvestites working in 7-Elevens and as flight attendants.