Back to selection

Back to selection

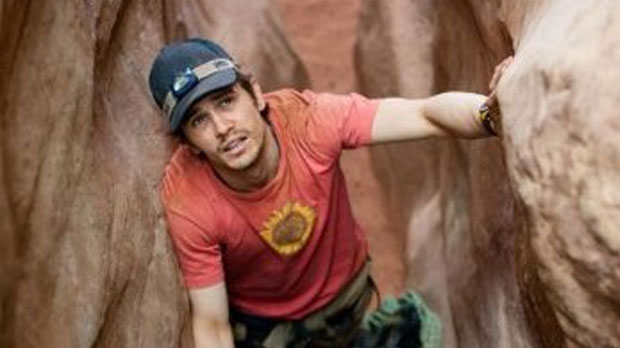

WHEN I GET OUT OF HERE: DANNY BOYLE’S “127 HOURS”

This piece was originally printed in the Fall 2010 issue. 127 Hours is nominated for Best Picture, Best Actor (James Franco), Best Adapted Screenplay (Danny Boyle & Simon Beaufoy), Best Editing (Jon Harris), Best Original Score (A.R. Rahman) and Best Original Song.

When Werner Herzog made his 1982 true-life inspired tale of a Peruvian capitalist transporting a giant steamer across dry land, Fitzcarraldo, he famously replicated the ordeal, lugging with his crew an even bigger ship across the Amazon jungle in one of the most strenuous and demanding movie shoots of all time.

Before its release, Francis Ford Coppola said of his own legendary production, “Apocalypse Now is Vietnam.” Decades later he elaborated to the Sunday Times, “I made it in a style I felt appropriate to the war itself: high amperage, big production, almost out of control. It wasn’t comfortable but I think it was right.”

“It wasn’t comfortable but I think it was right” — Coppola’s quote would fit right into my interview with Danny Boyle, in which the British director describes the making of 127 Hours, his follow-up to the Oscar-winning worldwide hit, Slumdog Millionaire. And while the decidedly more minimalist, intimate tale Boyle has chosen to tell couldn’t be further from Herzog’s and Coppola’s epics, he still shares with these directors a willful, obstinate, but finally thrilling belief in the relationship between a film’s production techniques and its emotional integrity.

Adapted from his memoir, Between a Rock and a Hard Place, 127 Hours takes us through almost a week in the life of Aron Ralston, an extreme “canyoneer” who, after falling into a quarry, is pinned to a rock for days until he engineers his release by self-amputating his arm. Boyle shot partially on the real location, with Ralston himself looking down as James Franco acted out the accident that almost killed him. For safety reasons most of the film was shot on a nearby stage, but if you think that resulted in a comfy shoot, think again. As he explains, Boyle created challenging and adverse shooting conditions in order to bring to his production some of the physical realities of Ralston’s ordeal. He also shook up film set orthodoxy, working seven days straight with not one but two d.p.’s, refusing to indulge the leisurely pace and perks that would naturally come to a director coming off as big a success as Slumdog Millionaire.

Could the film have been made in a more conventional fashion? Would the images have been the same? Would Franco’s performance, which is another high point in the career of one of the most fascinating actors around, be as strong? These questions may be beside the point, although for a movie largely taking place in one spot, 127 Hours has breathless energy, exciting emotional flow and weirdly inspirational quality. It’s clear that for Boyle to be able to dramatize a story whose ending audiences already know, a story with such a limited cast and reduced geography, he’d need to capture the intangible. With just a single actor on screen so much of the time, he’d need to find new ways to convey the dramatic beats that more extended dialogue-heavy scenes usually convey. In short, he’d need to make 127 Hours something more than a film about a guy who tears his arm off. Premiering to rave receptions at the Telluride and Toronto Film Festivals, Boyle has done just that, creating not only a gripping tale of adventure but also a meaningful meditation on nature, solitude and what it means to survive. 127 Hours opens from Fox Searchlight on November 5.

How did you first encounter this material? Was it as a book or a screenplay?

Well the first time was in 2003, actually, when I heard about [Aron’s] story. It’s not completely unique — there are other stories with some similarities — but there’s a purity about it that’s extraordinary, and I could never forget it. And then I was sent his book by [executive producer] François Ivernel from Pathé in 2006. I read the book, and I said, “Listen, François, I think I know a way to do this. I know it looks impossible, but I know a way that you can both be honest to the event, i.e. to show it [on screen], but also [in a way that] the audience will somehow be able to tolerate it, be able to sit through it. And it would be an immersive experience, not a documentary. You [the audience] would be trapped with him, and in some way you would help him get release because it’s your release as well.” I really believe that. It takes him more than 40 minutes to cut his arm off, and I think you’ve got to represent that. You can’t just do it out of sight. [The audience] must know: We have to go through this [experience] to get out of it. So it becomes a cathartic thing. That was the idea. Initially, Aron didn’t want to do it that way. He wanted to make it as a documentary, which I can understand completely. He had just finished a book, he was on a book tour, he was obsessed with being precise and accurate and factual. Whereas I was saying to him, “That’s not important. Let me do it so it’s emotionally truthful. It’s still a bit factual, most of it, but we also have to allow the actor to go through this experience, not to just copy you.” Anyway, [the project] kind of revived again after Slumdog. Aron had changed as a person. He was further away from the event. He’d met his wife, and they were going to have a baby. We said to him, “We’ll hand you back the story at the end, I promise. And you’ll be proud of it.” Which seems an odd thing to say, but I did believe that, and James [Franco] and I agreed. We would borrow it, we would hand it back to him at the end, and it’d be something he’d be very proud of. And he trusted us.

That’s a fascinating way to put it, that you’d have the audience participate in the creation of his catharsis.

We asked Simon Beaufoy, who wrote Slumdog, to write [the screenplay]. He’s also a climber, but he couldn’t quite see it. He said, “You should write a couple of drafts first,” and then after I wrote them, he could see it. So I knew I wasn’t explaining it very well, but basically it seemed terribly obvious to me that the shape of the story was that there were a couple of people at the beginning, angels, and they’re obviously people that he returns to at the end to help pull him back emotionally.

Was this structure present in the book?

Half the chapters [in the book] are about his solitude, and the other half are intercut and about his backstory — his research after the event about what people were thinking about him being missing and things like that. I was not interested in those other chapters. All I was interested in were the chapters of him trapped. I take my cue from my own instincts as to what the audience [wants to see] and what I want to deliver to them, and I knew it was just those chapters. But I’d say it’s very accurate to [his story], even though we took some freedoms. You just exclude the other things [in the book], so [Aron’s being trapped] becomes something that you are trapped [in] as well. A lot of people thought [the film] would be very difficult because [the story] is so inert, so static. And I said, “Yes, it’s static in one sense, but it won’t be inert. It won’t stand still, there will be a momentum about it if we can find the right actor.”

What was the process like of convincing people to make the film if that’s what they thought?

Well you have to be honest and say that success of Slumdog helped. [laughs] Quite a bit. And secondly, you just have to keep the price down. Because obviously the risk is, no matter what you say, what you deliver might be different or might be what some people suspect will be difficult to watch. So we kept the price down, and we took advantage of the Slumdog effect. And also, you can feel it in the story, there is an inspirational element to it. It’s an extraordinary compelling story of a struggle. At the beginning [Aron] is in many ways not a good guy. When he goes [into the desert] he’s reckless. There’s the physical fun he has with the girls in the beginning, but also, he’s been slightly reckless with people’s lives, like we all are. No big deal, but small things, and he has to come to terms with that. I felt the journey back to life would be very inspirational and would make a triumphant film, a triumphant experience that you’ll want to go on. I was always very confident but then directors are. You have to be. It’s part of the process. It’s up to other people to judge whether you’re right or not.

The beginning of the film, the material before he leaves for the canyon, has a real visual slickness to it; it felt to me that you’re deliberately using the visual vocabulary of advertising.

I wanted to pack as much pleasure in those scenes — you’re right, it is advertising. That’s the premise of advertising, isn’t it? To make a thing so pleasurable that you have to have it. [The beginning] is pleasurable so it will lure you into the film, but it will also make you and him aware later of what he is missing, what’s happened to him. Water, the film is saturated with water early on, the liquids that he takes for granted. They mean nothing to him, but he’s gonna have plenty of time to think about them for the next six days [laughs].

Tell me a bit about casting James. Was he somebody that you had in mind early on? How did he get into the project?

There’s a range in his work that’s quite difficult to find amongst really charismatic star actors. When you watch him in Pineapple Express or Milk or City by the Sea or Spiderman, there’s quite a range of work there, which is unusual in lead actors. Lead actors inhabit a role, and they don’t tend to do that kind of big, big range. But he can do it. I thought that was going to be really important. If we only have one person in the film, he’s going to have to beall the other actors as well, if you like. We’re going to need that contrast in him. And I also wanted someone who was prepared to be not an impersonation of Aron Ralston but to go on Aron’s journey himself. So it had to be someone who committed to the physical excesses of what we were going to go through and the way we were going to do it. He would be trapped there, and we wouldn’t help him. I wouldn’t let anybody in the canyon with him, apart from the cameraman. He wouldn’t get rigging help or props guys helping him. “Deal with it!” It was frustrating at times. We had this blood pact that he would never use his right arm for anything, even between shots. And it shows! He ended up doing these long takes — long, long takes — which were intolerable in one sense, but when you snip out a couple of minutes from them, it’s not like an actor acting it, it’s like he’s forgotten the process that he’s involved in. He’s just trying to make this fucking rope and trying to get this caravaneer attached to this other fucking rope with one hand. You get that truthfulness. So you have his skill as an actor, his ability to play contrasts, and you have these commitments. He doesn’t look at first sight like he is that kind of guy. He looks half-asleep half the time, James, but it’s a front. I found that out [as we went along]. It’s an absolute front. He’s super bright, and it allows him to kind of bypass all the big actor stuff. He’s as sharp as anybody I’ve ever worked with.

Let me ask you about the shooting, and working with two d.p.’s, Anthony [Dod Mantle] and Enrique [Chediak]. Why did you make that decision, and how did their collaboration evolve?

It was a conspicuous failure, to be absolutely honest, because my intention in getting two of them was not just so that I could shoot for seven days a week. My real intention was to create two different styles of shooting so there would be a contrast. We needed variety because what you have is so similar for six weeks. I thought, great, two different cameramen! Anthony, Northern European; Enrique, Latin American. That’s bound to produce two different styles. But [it was a] complete abject failure because what I hadn’t realized what matters is not that [idea], which is a slightly superficial approach. What happens to a cameraman is as soon as they start working with James, they develop a language with him, which I think James dictates as much as them. It’s impossible to tell their work apart now. What we got instead of contrast and styles was a coherent vocabulary and language about the way the film is shot. They would become organic with him, would move with him. The film just kind of flows with him, through these peaks and troughs and backward and forward. And that’s a tribute to the two of them.

How did the work actually break down? Was one person doing one type of material, and the other person another, or —

Sometimes we would shoot simultaneously. We would have the two of them somehow squeezed into the canyon to shoot stuff. Sometimes we would break up work. One of them would work like a five-day week, and the other one would work another five days, and I would go between the two units on the day they were working concurrently. One of them would work with a double, one of them would work with some of the specialized shots we did. And then obviously, I would just have a single unit on a number of days, because then one would be on the other’s day off. So I was able to keep going and keep the momentum going, which was amazing.

Were you shooting almost seven days a week?

Oh yeah, seven days a week. James — we couldn’t work James seven days a week and he had to have a day off, because he had to get to New York to his college, to keep that [going]. I mean, he did work seven days a week, just not on our film. He did six days a week on ours, and then he would fly to New York, show his face at college and then get back into that canyon again.

Why was it important to work seven days a week? I’m assuming it was a union film, so you are either eating the overtime, or you’re swapping crew people out. What was important to you about having that pace?

A momentum. A kind of intensity of momentum, not relaxing into it, not taking your time ever. And I thought that energy would seep through into the film. I believe that those are the right forces that will affect the film ultimately, how it’s made. And I thought the way to do this is, whatever you do, don’t stop, because I connected [that momentum] with him being trapped there. Whatever you do, don’t stop, don’t give up, keep going. [laughs] That’s just mad dialogue running in my head about that sort of stuff, really.

How many days did you shoot?

We did eight weeks altogether. One week in the canyon.

And the cave part, was that on location or was it on a stage?

We did one week in the real place, but you can’t film there entirely, because it was so isolated, and because of the danger. It’s very, very dangerous. The longer you spend in those places with a crew, the more likely you are that someone [will] have a terrible accident; it’s just the law of averages. So we built the canyon — we photocopied it, literally, and built it, replicated it. But the thing that we did that was unusual, and it affected Anthony and Enrique, and ultimately the way they worked with James, is that we made it so that you couldn’t move. We made it exactly as thecanyon. No walls moved, or anything like that.

No flyaway walls?

None of that. We made do with the available space that was there in the canyon. It was very frustrating for them sometimes, and awkward, but it benefited the film enormously, I think.

Wow.

It was very difficult to light because all the lights had to be from above. Normally what you do in a studio set is that you’d have gaps in the wall where you can get a light in and stuff like that. I thought, you’ll just spot that it’s fake. Anyway, I wanted to make it as immersive as possible, that you’re really there in the real place.

Earlier in this interview you used the word solitude, and that was something I thought about as I walked out of the movie. I thought of it as a kind of meditation on solitude. There’s of course that famous John Donne line, “No man is an island,” but for me, the film wasn’t a negative critique of solitude because you showed the beauty of solitude as well. I especially liked that Aron hasn’t given up his canyoneering at the end of the movie.

One thing that I realized, no matter what the rules might be for good drama, i.e., that [the protagonist] becomes a completely changed person — climbers don’t change. There’s something about them that you cannot change. Read the old books [by climber] Joe Simpson — there’s something they need. And that’s the benefit of a true story, because Aron still does go out there [in the canyons]. He needs that space again. But what he learns is that there are forces that work to bind us all together, and they’re invisible. Indeed Aron starts the film sort of despising these forces, these people and cities that he flees from, if you like. But ultimately, what saves him is his place amongst those people. He has a role as a father. He’s got a place other than beyond his own personal introspection. There’s something outside of him. And yeah, no man is an island. And Sartre was wrong — hell isn’t other people, hell is no one. Hell is no one, which is different from solitude. Solitude’s necessary for everyone at different times.

It’s a resonant theme right now, because it’s hard to be alone today. You have your BlackBerry, you’re on the Internet, you feel connected to your friends. You go on a vacation now and you have to make a decision: “Am I bringing these things, these devices?” I always fantasize about going on this really bold vacation and leaving the BlackBerry and computer at home. I think one’s relationship to solitude is something you have to think about more now than ever. It’s not something that naturally happens.

Yeah, and in fact to achieve it, of course, you have to do what he did. Extreme measures. Someone says about the desert, “Remember, it wants to kill you.” And of course, that’s where he goes, to seek that. He’s astonished when he sees girls out there. Of course, he has a little bit of fun with them but then he’s like, “No way.” He’s gotta get out, to find his own space again. So yeah, he goes to a very extreme place to achieve that solitude.