Back to selection

Back to selection

Cinema of Space

At his excellent BLDGBLOG, Geoff Manaugh offers a smart, original perspective on architecture by connecting it with various other disciplines including, this spring, film.

“It often seems like the most extraordinary spatial designs being produced today are not coming out of architecture offices but from the back lots of Sony or Lionsgate, where new places—sometimes whole cities—are dreamed up with an imaginative freedom you often find squeezed out of architecture programs in the name of historical rigor,” says Manaugh, a futurist who was previously a senior editor at Dwell magazine. “One thing that frustrates me about architectural writing today, for instance, is how rarely critics will look at anything other than real buildings. It’s far more likely that a new museum, with only 100,000 visitors per year, will be reviewed and discussed, while a multimillion dollar film set, seen by millions of people around the world, is somehow dismissed as nonarchitectural.”

In the summer of 2011, Manaugh changed coasts, leaving Los Angeles (“by far my favorite city in the United States”) for New York City to oversee, with his wife Nicola Twilley, Studio-X NYC. Funded by Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and located near the Holland Tunnel, Studio-X NYC is described by Manaugh as an “off-campus event space, gallery, classroom and urban futures think tank” devoted to exploring the future of cities. By definition an outside-the-box thinker, Manaugh pledged immediately to invite figures from “diverse backgrounds—natural history, epidemiology, crime and policing, fiction and film, architecture, archaeology, industrial design, psychology, comparative mythology, and more to give talks or organize small exhibitions” at Studio-X NYC.

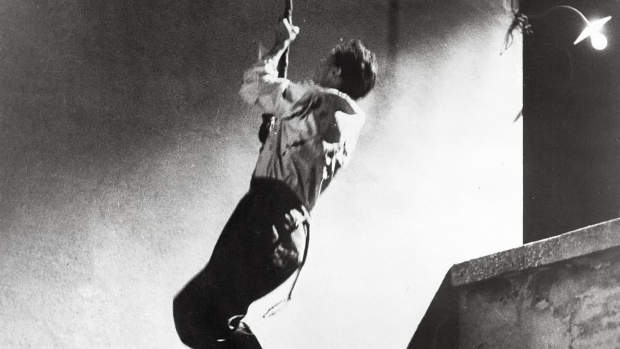

As a way of engaging people in a discussion of the relationship between architecture and film, Manaugh conceived Breaking Out and Breaking In: A Distributed Film Fest of Prison Breaks and Bank Heists. Described as “basically just a book club, with films,” the festival — which began on Jan. 27, and which has Filmmaker as a partner — involves people watching in their own home the movies chosen by Manaugh, and then discussing them on Manaugh’s blog. The diverse slate of films ranges from classics of French cinema, such as Renoir’s Grand Illusion, Bresson’s A Man Escaped and Dassin’s Rififi, to recent Hollywood titles such as The Italian Job, Inside Man and Inception.

Asked about why heist films and escape movies are such a perfect entry point into a dialogue about cinematic architecture, Manaugh explains, “Buildings are like puzzles: when you go into a new building, you’re immediately looking for doorways out or halls leading to the next room. You try to figure out the space you’re in—to find the bathroom, to locate the stairs—or you start wondering what’s behind that closed door. Escape films and break-ins just foreground all that; they turn the setting itself into the engine of the story. It’s like the labyrinth scene in The Name of the Rose, where Sean Connery’s character advises Christian Slater how not to get lost: the spaces around us have rules and limitations, and we can either learn those rules and use the space properly, or we can find ways to cheat, to go through walls, to sneak into places we’re not supposed to be. Prison escapes and bank heists supply a kind of counter-manual, you might say—a how-to guide to misusing space.”

For Manaugh, the film that uses cinematic space most interestingly is Die Hard, a film which, to the undiscerning eye, is just a straightforward Hollywood action blockbuster. “Die Hard explicitly foregrounds the experience of architecture, with characters moving through a Los Angeles skyscraper seemingly only in ways that the building’s architects did not expect or anticipate,” says Manaugh. “We see people riding on top of elevators and forcibly stopping the cars between floors; they visit whole sections of the building that are still under construction; they shoot through doors and throw each other through walls; they crawl through air ducts; they leap off the top of the building before swinging back in again through broken windows; and all of this is in addition to the central heist sequence, which involves hacking—then drilling—through a series of sealed vault doors.”

In addition to analyzing with refreshing erudition our favorite bricks-and-mortar heist and escape films, Manaugh has also opened up the conversation to include Inception and The Truman Show, two films in which the challenge of breaking out or breaking in transcends the physical. “The Truman Show was suggested by an architectural writer and colleague of mine, Jimmy Stamp,” says Manaugh. “I thought it was a brilliantly outside-the-box take on the idea of breaking out, and one that adds to the discussion in countless ways, so we included it. And Inception is almost famously easy to discuss—maybe not easy to discuss in an intelligent way!”

The three-month festival culminates in a live event at Studio-X NYC on April 30, at which Manaugh has lined up a diverse group of speakers — including the aforementioned Stamp, a writer and architectural historian — who will share their views on both movie genres. “By organizing the night into two discussions—one on prison breaks, the other on heists—we’ll get a chance to go back through the films and discuss all of the festival’s major themes, but we’ll also see what crosses over between the two,” says Manaugh, who aims to have everyone from armed robbery detectives to movie industry figures at the free, open-door event.

Manaugh has plans for future “distributed” film fests based around haunted house movies and cinematic car chases, but for now is just hopeful that Breaking Out and Breaking In will spark a change in attitude. “I’d love to see more back and forth between the worlds of film and architecture—with actual practicing architects being invited to design sets for blockbuster films, and film set designers being taken more seriously in architecture school,” he says. “If a film fest like Breaking Out and Breaking In can help catalyze those sorts of discussions and future collaborations, then I would be thrilled.”