Back to selection

Back to selection

Toronto International Film Festival 2012

Harmony Korine's Spring Breakers

Harmony Korine's Spring Breakers The increased emphasis on red carpet and premiere status in Toronto seems to have left the festival with an identity crisis. Compared to festivals like Locarno and Rotterdam, which have hit their stride in promoting the new guard of international cinema, just a quick glance at this year’s program guide makes it clear that the “Festival of Festivals” is in the midst of redefining itself.

Wavelengths, formerly a sidebar of avant-garde shorts programs, has expanded to include the section previously known as Visions. Many of the more interesting films in the festival could be found here, including the much-buzzed-about Leviathan and Miguel Gomes’ Berlin favorite Tabu. My personal favorite, however, was Walker, a new work by Tsai Ming-liang originally produced for the omnibus film Beautiful 2012.

After the Louvre-funded, episodic bombast of Visage, Walker finds Tsai stripping his filmmaking down to its barest essence. Muse and collaborator Lee Kang-sheng dons the scarlet robes of a monk as he walks with head down through the bustling streets of Hong Kong at the pace of a slow-motion snail. The harried and bemused passersby point or take pictures with their camera phones while Lee, with a sandwich in one hand and a plastic bag in the other, steps through Tsai’s immaculate frames motivated by mysterious timings and rhythms.

Running at a spare 26 minutes with no dialogue, Walker is a profound experience. The absurd humor that punctuates this simple concept (spoiler alert: the “climax” of the film is Lee finally biting into that sandwich) belies its emotional, spiritual and even political complexity. By putting a walking still life on the same continuum with modern Hong Kong, Tsai not only challenges us to rethink our own pace, but issues a direct rebuttal to the at-all-costs priorities of global capitalism. This is an incredibly controlled offering, but thankfully said control is neither neurotic nor despairing.

Although his new feature Museum Hours was presented in the Contemporary World Cinema section, Jem Cohen is a filmmaker who would have been just as at home in Wavelengths. His previous feature, Chain, was one of the most surreal and pessimistic films of the last decade, an exacting evocation of the psychic dislocation fomented by the megamalls, chain stores and airports that served as its guerilla sets. Museum Hours, although it returns to themes of displacement, is a much more optimistic film about the ways in which art can be not only a spiritual salve, but also a catalyst for connection and friendship.

In Chain, we follow a Japanese businesswoman who finds herself in the United States on a research trip; in Museum Hours – also shot on location, at the Kunsthistorisches Art Museum — Anne (Mary Margaret O’Hara) is a Canadian who finds herself in Vienna when a cousin falls seriously ill. When museum guard Johann (Bobby Sommer) stumbles across Anne attempting to make heads or tails out of a city map, he offers to show her around, noting that if he were lost in Toronto, he hopes that someone would do the same for him.

In a traditional narrative, Johann and Anne would fall in love. Instead, Museum Hours uses this expectation as a point of departure. Johann, who narrates the film, has slipped into a life as a spectator. Provoked by Anne’s presence, he steps away from the online poker games that previously took up his leisure time and reintegrates himself into the world. Juxtaposing the pair’s developing friendship with images of bored teenagers in the main gallery, a docent patiently discussing the virtues of Brueghel with an unpleasant patron, and other “documentary” footage, Cohen establishes a complex grid of relationships — between art and life, documentary and fiction, countries, inspiration, memory and voyeurism — with grace, intelligence and a deep humanism.

Taking a step back to its earliest days, the festival itself offered a chance to revisit past masterpieces via a Cinematheque section of new restorations. With landmark titles ranging from the Canadian indie Bitter Ash to Ritwik Ghatak’s 1960 Bengali breakthrough The Cloud-Capped Star, this was a broad selection of films, although it was disheartening that the majority was screened on DCP.

In his film note for The Cloud-Capped Star, curator James Quandt drew comparisons with Mizoguchi as a point of departure for Ghatak. Like Mizoguchi’s heroines, Ghatak’s Nita is a woman of superhuman strength who endures profound suffering for those who don’t necessarily deserve it: her family. Unlike Mizoguchi, however — or his contemporary Satyajit Ray — Ghatak leans toward the avant-garde in his critique of social structures, most prominently in his use of nondiegetic sound. At once a moving piece of family drama, a passionate plea for social change, and an expressionistic, idiosyncratic work of art, The Cloud-Capped Star presents Ghatak as a radical filmmaker (even — perhaps especially — by today’s standards) who deserves the honors he was never afforded during his lifetime.

The source of the occasional snickers at the premiere of Brian De Palma’s Passion were all too clear: those who considered themselves to be above the director’s “trashy” remake of Alain Corneau’s Love Crime, starring Rachel McAdams and Noomi Rapace. Here McAdams dusts off her persona from Mean Girls and reimagines her as a serpentine ad exec, Christine, who takes credit for the jeans campaign created by her underling Isabelle (Rapace).

In the mode of such self-aware meta-films as Raising Cain and Body Double, De Palma consistently plays with form and genre, calling attention to the cinematic mechanism at every opportunity riffing on product placement with a comically large close-up of an Apple logo, pointedly using actors from every country that had a stake in the production, and utilizing the film’s intellectual property plot to create a running commentary on the very idea of remaking and remodeling. And, like all De Palma films, there are screens within screens (Has any director so keenly anticipated the self-induced culture of voyeurism we live in today?) and dreams within dreams.

Another master of genre play is Ben Wheatley, who has been unofficially anointed as the new voice of British cinema despite only having three features to his credit. His latest film, Sightseers, a road movie about an average couple who turn out to be anything but, tones back the wild ambition of his hitman-horror-hybrid, Kill List, and revisits the direct dark comedy of his debut Down Terrace. Tina (Alice Lowe) lives in quiet desperation with her unhappy, verbally abusive mum, but when she meets Chris (Steve Oram) she thinks she’s found her knight in cargo pants. The couple take to the countryside in Chris’s RV, but the pent-up rage that lies beneath their on-holiday exteriors is soon redirected towards litterbugs, bourgeois tourists and anyone else who gets in their way.

Once again, Wheatley demonstrates his immense talent for playing against audience expectations and reviving genre in unique and unexpected ways. Tina’s kitchen-sink existence calls to mind the social realism of a Ken Loach; her pairing with Chris one of Mike Leigh’s more generous character studies. Come the first murder, we’re in darkly comic territory far from the standard conventions and characterizations of working-class authenticity — imagine a version of Happy-Go-Lucky in which Eddie Marsan’s bitter driving instructor actually starts killing people and you get the idea.

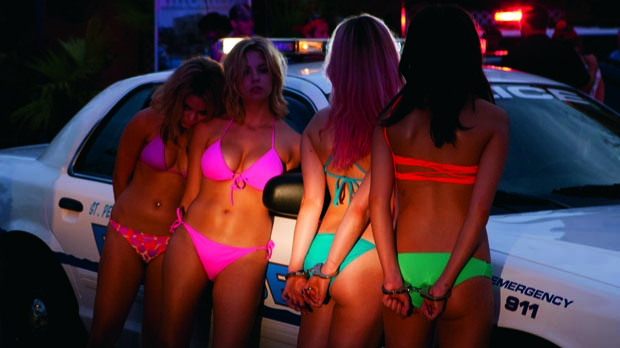

Finally, no discussion of TIFF 2012 would be complete without a mention of Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, an even hotter ticket for press and industry members than Terrence Malick’s maligned To The Wonder. A high-concept piece of low art, the film stars teen princesses Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens and Ashley Benson (as well as Korine’s wife, Rachel) as a group of Nowheresville coeds who rob a Chicken Shack to fund a trip south for spring break (represented throughout the film by Skrillex-scored montages of boob-and-beer filled debauchery). Hooking up with gangsta-wannabe Alien (James Franco), the girls and their soul mate-in-crime soon take back the streets from Alien’s rival Archie.

Korine doesn’t provide much backstory for his characters, but he doesn’t need to. Clad in pink, carrying cellphones, and goofing their way through class, these college girls are the blemish-free face of consumerism, fueled by white privilege and political apathy. One gets the sense that Korine’s touchstone is as much Miami Vice as the gangster cycle of the 1930s, wherein street-level gangsterism is analogous to big business. Who knows what kind of havoc these girls will wreak once they finally get their business degrees?

Technically, it is as accomplished as anything the director has ever done. Collaborating with cinematographer Benoît Debie, Korine makes the Floridian coastline’s inherent sleaze strangely beautiful and dreamlike. The screen pops in garish tribute to pink flamingos, black lights and Jolly Rancher-colored cocktails, suckering the viewer into agreement with Franco’s sinister, whispered call to action: “Spring break forever.”