Back to selection

Back to selection

Back to the Future with 4K: Large-Sensor Motion Picture Cameras in 2013

Sony PMW-F55 with OLED viewfinder and AXS-R5 RAW recorder.

Sony PMW-F55 with OLED viewfinder and AXS-R5 RAW recorder.

A motion picture camera used to be a light-sealed box with a strip of film running through it. Was it easy to thread? Did it run quiet? How bright was the viewfinder?

Today’s cameras are exponentially more complex. They are literal bundles of separate technologies, each lurching forward at a different rate. To understand today’s cameras, you must understand the parts to understand the whole.

This is my third annual overview of digital cinema cameras for Filmmaker, and it is being written in the run-up to NAB 2013 in Las Vegas, the world’s largest trade show devoted to digital video and broadcast equipment. By the time some of you read this article, NAB will have ended, and there are certain to have been surprises. But they will fall within the framework of what I describe below, which you can use to handicap NAB 2013 and future NABs, too.

This year, I feel that contextualizing the changes underway is more important than rattling off descriptions of new products and gear. There will be a torrent of such hype across the Internet when NAB takes off, anyway.

What follows is a series of sketches of where things stand and what to look for going forward. At the end, I’ll briefly touch upon the latest in new cameras.

This year’s main story is the industry’s open-arms embrace of 4K.

PIXEL COUNT

• Full HD — 1920 x 1080 — is destined to become the lowest available camera resolution. No more 4:3 or SD. While parts of the world will demand 4:3 SD for television production for some time to come, this development is fated. Next question, should 1280 x 720 survive?

• We now live in a Retina Display world. It’s possible someday little kids won’t remember a time when pixels were visible. The big news at the Consumer Electronics Show in January was Ultra HD, a rebranding of what until January was called 4K or Quad Full HD (QFHD). While this 3840 x 2160 format for the home looks best on displays of 80 inches (!) or more, the TV industry is gearing up to introduce more-affordable 55-inch and 65-inch 4K sets by year’s end. I live in a Manhattan apartment. Thoughtful of you, TV industry.

As a maker, is it time to freak out? Ultra HD is four times the data of HD. Whatever storage you use for capture, editing and archiving, multiply that times four. Imagine your favorite NLE chugging through it. Entertain the thought of dumping your pricey HD camera for a 4K camera. You’ll want to upgrade your lenses, too.

Incidentally, “Ultra HD,” until quite recently, was used by Japanese broadcasting (NHK) to denote the 8K system they’ve showcased at NAB for several years running. We’re talking 16 times the data of HD. This is something they intend to broadcast. There are those in Japan who consider 4K an interim step to 8K and would like to skip it. I wish I were making this up.

But whether we call it Ultra HD (3840 x 2160) or cinema 4K (4096 x 2160) — the format delivered by DCPs — 4K is here to stay.

Defining what is and isn’t a 4K camera, however, gets tricky.

The first 4K camera, the ill-fated Dalsa Origin of 10 years ago, used a Bayer color filter array like RED and most self-described 4K cameras today. Although their sensors provide 4096 photosites across each pixel row (hence 4K), their checkerboard-like Bayer color filter produces only 2048 green samples per row, at half the horizontal resolution. Red and blue samples represent a quarter of the sensor’s overall resolution.

This missing color information must be invented or “interpolated” on a pixel per pixel basis — a process called demosaicing or deBayering.

Shouldn’t each pixel get a full RGB sample? This is the crux of a long-standing and, at times, quasi-religious argument about what truly is and isn’t a 4K sensor. It’s why Sony’s F65 uses an 8K sensor to output 4K, producing a full green sample for each 4K pixel and, overall, half as many red and blue samples. Not perfect, but better.

If we, instead, define a 4K camera by its output, whether RAW or deBayered and compressed, rather than by its sensor, then today’s crop of Super 35 4K cameras includes RED EPIC/SCARLET/ONE, Sony F65/F55/F5/FS700 and Canon C500. Non-Super 35 4K cameras include Canon 1D C, Phantom 65 Gold, JVC GY-HMQ10 camcorder and, believe it or not, the $400 GoPro Hero3 at 12 fps.

In any case, 4K acquisition has already set sail. At least eight Hollywood films are currently being shot in 4K using Sony’s F65, including After Earth (Will Smith), Oblivion (Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman) and Motel (Robert De Niro).

In any case, 4K acquisition has already set sail. At least eight Hollywood films are currently being shot in 4K using Sony’s F65, including After Earth (Will Smith), Oblivion (Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman) and Motel (Robert De Niro).

Those 4K DCI-compliant projectors that already inhabit commercial projection booths? It’s as if they’re waiting for this Hollywood 4K content to arrive.

So maybe this is the final juncture to ask, post facto: Why 4K? Weren’t HD and 2K good enough?

One answer — a serious one — is that you can’t be too rich, too thin, or start out with too much resolution. I take stills with my Canon 7D that are 5184 x 3456 pixels. I view them on my MacBook Pro. They might be good enough, perhaps, to print a poster from. I wouldn’t dare project them on a cinema-size screen. Yet we do this every day with 2K and HD digital images less than half the size! Or, put another way, with 2K and HD images containing less than a quarter of the pixels found in each of my stills.

(I’ll skip the cynical answer, the one about an industry seeking the next big thing to shake up a sluggish consumer market saturated with flat-screen TVs they haven’t yet paid off. And still smarting from the 3DTV fizzle.)

Here’s a fun fact: the count of 4096 pixels across derives from a 1980s Kodak study of the resolution necessary to preserve all the detail in a frame of Super 35mm color negative during a digital scan.

How much of that 4K resolution ever made it to the big screen? Given that a 35mm master positive was first struck on a contact printer (from an Academy frame with fewer than 4096 pixels across), then a dupe neg was struck from the master positive for release printing, then the release print was struck from the dupe neg? Let’s not forget projector jitter, gate buckle, out-of-sync pulldown, an oil-splattered lens not sharp across the screen, keystoning and that smudged port glass!

Answer: never more than 1.3K.

4K on the big screen is something we’ve never seen before.

From 4K-originated work I’ve seen projected as 4K, I can tell you that 4K can be sensational. Enhanced resolution that you can feel, if not see. The next best thing to watching 35mm film dailies in a lab projection room.

Will we see this at home, assuming we have an 80-inch 4K TV? At present, cable can’t deliver this huge signal. Blu-ray can’t either. Both will, at some point, using compression twice as efficient as today’s H.264. At the moment only RED Digital Cinema’s REDRAY 4K Cinema Player ($1,450) can play back compressed 4K and upscale your HD to 4K for playback.

One reason for the delay in 4K home media may be fear of piracy. 4K acquisition for filming a studio project is one thing. A large 4K display in the living room not under studio control is something else: a pixel-free palette from which to shoot a perfect copy.

To the industry: Be careful what you wish for.

SENSORS

• ISO creep: the latest Super 35 sensors vastly improve signal/noise, which has hiked possible gain settings to +30 dB (Sony FS100, FS700) and ISOs up to 20,000 (Canon C100, C300, C500). This is the new normal. For instance, the base ISOs of Sony’s new F5 and F55 using S-Log2 are, respectively, 2000 and 1250. Fixed pattern noise, which reduced the usefulness of high gain in early Super 35 sensors, is a thing of the past.

• Three-chip cameras are out. Three chips triple cost and complexity. They require a beam-splitting prism. Can you imagine the size of a prism needed for a Super 35 sensor camera? The cost? The lens modifications necessary to offset image distortion inflicted by the prism? Historically, 3-chip designs are an anomaly, like three-strip Technicolor. We’re back on track now.

• Super 35 is, and will remain, the de facto standard for single-sensor motion picture cameras. Micro Four Thirds and DSLR full-frame will be niche at best.

Super 35, by the way, is the latest name for the original motion picture film frame introduced in 1889. The story, possibly apocryphal, goes that Eastman asked what size flexible film Edison’s camera required. Edison held up his thumb and forefinger and Eastman got a ruler: 1 3/8 inches. 35mm.

So we can say that from the outset of cinema, camera negative has been Super 35 analog 4K.

Only now it’s Super 35 digital 4K.

Back to the future…

• A significant advantage of CMOS over CCD is windowing. With CCDs it’s the entire image or nothing. But you don’t have to use an entire CMOS surface to capture an image. A smaller, cropped area can be read out and recorded instead. This is possible because CMOS photosites are individually addressed. Some can be activated, others ignored.

Imagine, using your Super 35 camera and an 85mm Compact Prime, shooting an interview with narrow depth of field and softened background, then mounting a vintage Super 16 zoom to your camera and switching to a Super 16 size area of your camera’s sensor. In other words, you’ve electronically converted your camera from one sensor size to another to gain greater depth of field for handholding. Why not?

Windowing already exists in Sony’s inexpensive NEX-EA50, where it enables 2x zooms using prime lenses, and Canon’s full-frame 1D C, which crops its full sensor to accommodate Super 35 lenses with their smaller image circle. Expect windowing, still a novelty, to mature into an essential tool. Camera manufacturers, are you listening?

LENSES

• A single chip invites a shallow flange-focal depth (there’s no prism), which permits inexpensive adapters for any lens with adequate coverage. This, in turn, opens the door to a universe of cheaper SLR lenses, including tilt-shift and catadioptric (using mirrors) specialty lenses.

• Super 35 is synonymous with (but does not require) lens interchangeability. Two lens-mount standards prevail, ARRI’s PL (Positive Lock) and Canon’s EF (Electro-Focus). PL cameras feature a locking ring that turns to tighten down on a three-flanged lens mount, insuring mechanically secure seating. Canon’s C500 has introduced a new locking-ring version of EF that feels as solid as PL. These clamped, tightened-lens mounting systems are best. By comparison, conventional EF lenses twist and lock, bayonet-style, often accompanied by a small degree of looseness and play. Same for Sony’s E-mount and A-mount.

Sturdy, load-bearing lens mounts are critical because, compared to small-chip cameras, Super 35 cameras require larger lenses. Large cine-style zooms can weigh more than the camera (cost more, too). One reason why primes — faster, lighter, cheaper — are encountering newfound popularity.

• Growing use of primes, in turn, brings back dollying for camera movement, as seen in the explosion of sliders, skateboard dollies and rolling jibs. Which brings back focus control knobs and focus-pulling.

• Communication between lenses and cameras is growing. Design of primes has split between traditional passive mechanical control — although some, such as Cooke 5/i and Zeiss Master Primes, provide metadata to describe their settings — and active electronic control, such as Canon’s EF series. In addition to automation of focus and iris, electronic control of lenses confers compact size and a constant flow of metadata (useful for motion control). Manifold contacts, usually gold, convey data and power. As with power steering and brakes, you can’t drive these babies without juice.

• Zooms for Super 35 present a particular challenge. Angenieux, Cooke and Zeiss zooms common on feature film sets are necessarily huge, heavy and expensive. Optical performance demands it. What about small Super 35 cameras? There are no magic bullets here. Although the “silver bullet” 18-200mm that accompanies Sony’s FS100 and FS700 is a good example of adapting a DSLR-type zoom design to cine use. Its lightness and optical image stabilization are often welcome. But tradeoffs are too obvious: a slow f/3.5 maximum aperture and when zooming to 200mm, a dramatic “ramping” (light loss) of maximum aperture — f/3.5 to f/6.3 — accompanied by a comical erection, which prevents use of a matte box.

Adding servo motors to larger Super 35 zooms, as is typical with ENG and small camcorder zooms, has been a challenge. Larger lens elements require bulky servos. Which adds weight and price. So the fact that Sony recently added a zoom servo to the 18-200mm (kit zoom for Sony EA50) while preserving its lightweight, compact profile is notable. Stay tuned.

• Hand-holding a Super 35 camera remains a circus trick, notwithstanding third-party shoulder-mount rigs with handles. Depth-of-field is shallow, and unforgiving focus must be constantly checked. This especially impacts on-the-fly documentary work. Any camera handgrip without a focus magnification button is a joke. Best so far is Canon’s, shared by the C100 and C300. Near the thumb is a button for 2x magnification, as well as a flat joystick for full menu access. At front, above the start/stop button, is a control dial for the right index finger that can adjust gain/ISO or f/stop when using an EF lens. All that’s missing is one-push auto-iris. Sony’s FS700 grip has a button for that, plus 4x and 8x magnification. At 8x, focus gets nailed fast (although even great lenses can suddenly look questionable).

Since it’s difficult to shoulder a Super 35 camera and operate its lens at the same time, continuous autofocus, once the scorn of pros, is receiving fresh interest. Sony’s NEX-FS700, for instance, offers two types of autofocus: 1) intelligent “face detection” when using the 18-200mm kit lens, in which the camera identifies faces and keeps them in focus by tracking fine-detail contrast (unreliable in low light); and 2) “phase detection” autofocus, which requires a special Sony lens adapter and Sony A-mount still-photo lenses. Phase detection works on a beam-splitting principle and operates well in low light. (I know these sound alike. Here’s a demo of phase detection I created a year ago.

MEDIA

• For new cameras, acquisition is an entirely solid state. No exceptions. Backup can be spinning disks, linear tape or perhaps cartridges filled with archive-quality, multi-layer Blu-ray discs. (Sony and Panasonic are launching such systems.)

• Two-and-half-inch SSDs (solid-state drives) are heaven-sent. They’re compact and commodity-cheap. Sony’s dedicated SSD, the HXR-FMU128 Flash Memory Unit, has been around since 2008 and docks to the latest FS100 and FS700. Blackmagic Design’s Cinema Camera swallows an off-the-shelf, 2.5-inch SSD whole. And 2.5-inch SSDs have inspired a new product category of compact uncompressed/compressed recorders from Blackmagic, Atomos, Convergent Design and Cinedeck.

• Media is both accelerating and shrinking (opposite of the universe, per Einstein, which is accelerating and expanding). Announced a year ago, Panasonic will introduce at NAB a faster (1.7x) and cheaper P2 replacement, microP2. Strikingly smaller than the original, microP2 is actually a UHS-II SD card (Ultra High Speed), the first to market. $380 for a 64GB microP2 vs. $650 for an F-series 64GB P2 card. Small cards make for smaller cameras, they say.

Sony prefers its media beefier. Two years ago they introduced SR Memory, a super-fast, solid-state card the size of a 2.5-inch SSD or iPhone 4 in capacities of 256GB, 512GB, and 1TB. A 1TB SR Memory card inserted in Sony’s compact, onboard SR-R4 Memory recorder lets an F65 capture an hour of 16-bit RAW at 24fps. That’s the good news. The bad news is that, depending on read/write speed, 1TB cards start at $6,000. Okay, so it’s bulletproof. You can yank it while recording and your $200M tentpole won’t lose a frame, no less collapse. Which makes these cards strictly rental items.

For the AXS-R5 RAW recorder module that piggybacks to the new F5 and F55, Sony has inaugurated another super-fast memory card, the AXSM 512GB (only one size). The new card is robin egg blue, the width of an SR Memory card but stubbier. Street price $1,800. Did I mention a 2.4 Gbps write speed fast enough to record compressed Sony 4K RAW to 60fps and 2K RAW to 240 fps?

Even SxS is getting turbocharged. For the new F5 and F55, which record internally to SxS, there’s a new SxS Pro+ card with best-in-class write speed of 1.5 Gbps for HD, 2K and 4K video. It comes in 64 and 128 GB sizes only.

FRAME RATES

As camera bandwidth increases — CPUs, internal data buses, digital signal processing, codecs, outputs get faster — possible frame rates climb. A recent example is Sony’s NEX-FS700, which captures 1920 x 1080 up to 240 fps, or up to 480 or 960 fps with some loss of vertical resolution. Canon’s C500 captures full HD and 2K up to 120 fps. At present, these high frames rates are used for slo-mo effects. For those interested in HFR, the high frame rate of 48 fps exuberantly introduced by Peter Jackson in The Hobbit, you have an ally in the International Telecommunications Union, which last year added a new frame rate of 120p while standardizing 4K and 8K Ultra HD. Some at the ITU evidently felt that at these stellar resolutions, legacy 60p looked jerky.

COMPRESSION AND LATITUDE

• RAW is simple… Signals are captured directly from the sensor. They’re unprocessed, unless they’re not: Canon bakes in ISO and white balance. They’re uncompressed like ARRIRAW and Canon Raw, unless they’re compressed, like REDCODE RAW and Sony RAW.

The idea of RAW, however, remains simple: to capture a sensor’s full output and put off decisions regarding color and gamma correction until later, in a proper post environment. RAW also serves as a means of compression, in that RGB are first subsampled by the Bayer color filter before the RAW signal is formed. In the 4K era, when all manner of data reduction is welcome, internal RAW recording will appear in all digital cinema cameras, not just high-end.

Blackmagic Design’s $3,000 Cinema Camera, for instance, records 12-bit RAW internally to its SSD. (Which RED EPIC trailblazed with “REDMAG” 1.8-inch SSDs). By mid-year, Sony will offer upgrades to its $8,000 FS700, which internally records AVCHD, to enable output of 16-bit 2K RAW and some form of 4K. The “refresh” of ARRI ALEXA, described below, adds internal 2.5-inch SSD recording of uncompressed ARRIRAW.

• Just as RAW extends the reproducible dynamic range, so, too, for video, do log gammas such as Sony’s S-Log2 and Canon’s C-Log preserve highlight detail at 800 percent of nominal peak white, inspiring manufacturer’s claims of 14 stops. (Your mileage may vary.) Like RAW, these film-like gamma functions produce flat-looking images that require color and contrast adjustment in post. (Unless you’re shooting Lena Dunham’s flat-looking Girls.)

If shooting with RED EPIC or ARRI ALEXA, you may also apply one of their respective HDR (High Dynamic Range) methods for taming overexposed scene elements. HDR is probably familiar to most people for its inclusion in their iPhone camera options. The more advanced motion picture HDR doesn’t solve every issue relating to tonal reproduction, but I suspect some form of HDR will make its way into every digital cinema camera, akin to RAW.

Meanwhile, standard REC 709 gamma and its Ultra HD counterpart, REC 2020, will remain the uncreative but simpler option for capturing HD and Ultra HD video.

• No compression, no 4K and 8K. Capturing uncompressed signals is admirable in principle but wishful thinking as data throughputs multiply exponentially. Which compression is best?

MPEG-2 remains the basis of most broadcasting, satellite and cable video, as well as DVDs. But its days are numbered. H.264 is twice as efficient, meaning you get the same quality at half the data rate. And H.265 will be twice as efficient as H.264. If you were a broadcaster, would you rather broadcast one channel or four channels in the same space? Who wouldn’t want the capacity of their camera’s acquisition media to quadruple?

H.264, the MPEG-4 root of AVCHD, is 10 years old. Remember how our NLEs once choked on AVCHD? Doubled efficiency requires more than doubled computational power, particularly to encode. Future compression gets only more complex, placing unprecedented demands on our multicore laptops, workstations, media and drives. Thank goodness for Moore’s Law, Thunderbolt and USB 3.0.

H.265 (HEVC, or High Efficiency Video Coding), which passed the first stage of standardization in January, promises 4K at 25 Mbps, same as DV from 1995. Some other time we’ll discuss the intricacies of H.265, how it exploits larger, more flexible macroblocks using improved predictive tools to achieve better motion compensation. That’s a mouthful for how this latest long-GOP interframe compression will deliver 4K by cable and optical media to the home and open the door to low-cost recording of 4K by camcorders.

Meanwhile, for high-end HD, Sony will stick with intraframe MPEG-4, long-time basis of their SR codec. With a free firmware upgrade due in July, both F5 and F55 will record SR to SxS Pro+ cards at 4:4:4 (440 Mbps) and 4:2:2 (220 Mbps).

Both new Sony cameras also introduce a new high-end video codec, XAVC Intra, 10-bit, 4:2:2, based on the highest possible level (5.2) and profile of the H.264 standard. Using new SxS Pro+ cards, the F55 records 4K XAVC Intra up to 60p — 4K video to an internal card is a world’s first — and 2K up to 180 fps after a free firmware upgrade this fall. The F5 records 2K up to 60p and, with free firmware also this fall, 120 fps. Meanwhile, don’t toss those older SxS Pro cards, good for XAVC Intra at 60p and under.

XAVC has already demonstrated so much promise, Sony decided to expand the format to spur a consumer 4K market. The just-announced XAVC S will be long-GOP, 4:2:0 for 4K and 4:2:2 for HD. Consumer 4K Handycams, anyone?

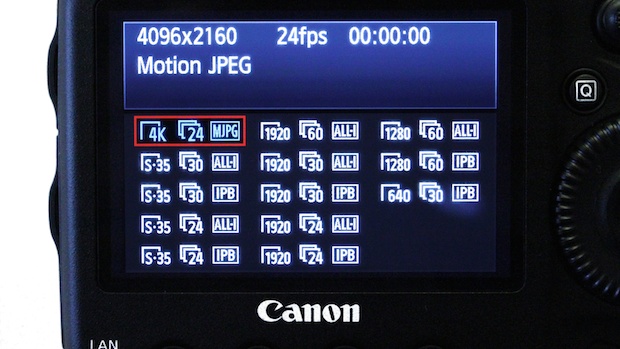

Canon has introduced intraframe 4K recording in their 1D C, the cinema version of the 1D X DSLR. The 1D C records 4096 x 2160 (windowed from the center of its 5208 x 2160 full-fame sensor) at 24 fps (23.976) using an 8-bit 4:2:2 Motion JPEG codec. Data rate to CompactFlash media is a blazing 500 Mbps, about 3.76 GB/min. CF card must be UDMA 7, at least 100 Mbytes/sec. (For comparison, Sony’s XAVC at 30p is 300 Mbps.)

Panasonic introduced AVC-Intra 50 and 100 Mbps camera acquisition formats in 2007 and continues to pioneer intraframe MPEG-4 as part of what they call their AVC Ultra family. Latest developments in 200 Mbps and beyond, including 12-bit 4:4:4 and 4K, will be on display at NAB.

ARRI’s ALEXA stormed the world of TV production in three short years partly on the image quality and workflow efficiencies of ProRes 422 HQ and 4444 captured directly to Sony SxS cards. Last year, ARRI added support for Avid’s ProRes equivalent, DNxHD, now an open standard. Convergent Design’s new Odyssey hybrid recorder (discussed at end of this article) offers support for ARRIRAW, Canon RAW, DNxHD, but no ProRes. Blowback from the industry’s shock at FCP X?

Perhaps. Although ProRes already supports 4K, post houses now reportedly prefer DNxHD for 4K. No question that after Apple abandoned FCP 7, some FCP 7 users abandoned Apple. Only don’t count Apple out. In their eighth major FCP X upgrade in less than two years, Apple just added native support for Sony’s 4K XAVC codec introduced in the F5 and F55. And Avid’s enduring business woes haven’t exactly reassured the pro editing community.

CAMERA DESIGN AND CONTROL

• Cameras have been computers with lenses for some time. As such, it should come as no surprise that wireless and IP technologies have made inroads. When Hurricane Sandy struck New York, winds prevented use of satellite and microwave trucks for news reports. Instead something called “bonded cellular” came into dramatic use. The idea is simple: camera signals from the field are divided over multiple telephone cellular networks — ATT, Verizon, Sprint, T-Mobile — to ensure arrival for broadcast. These bonded cellular systems piggyback to cameras, clip to belts or fit in briefcases.

At NAB, Panasonic will demo a firmware upgrade to one of its ENG camcorders that opens a USB connection directly to bonded cellular systems, allowing the camera operator to start and stop uplinks. Panasonic and others at NAB are also showing live camera monitoring and control over IP (Ethernet). Can smartphone and tablet monitoring/control apps over Wi-Fi and Bluetooth be far away, even for budget camcorders?

Take a look at RED’s MEIZLER MODULE for EPIC co-developed with 3ality Technica to see what full wireless control, including 1080p uncompressed video transmission at 5GHz, can achieve.

• RED was ribbed for its work-in-progress attitude toward launching new Super 35 cameras — must we now pay for the privilege of beta testing? — but damned if the industry hasn’t followed suit. Blue-chip manufacturer Sony launched its F5 and F55 with announcements of significant features to be added via firmware updates over the Internet. What next, the App Store?

• Modularity, as championed by RED, is the order of the day in Super 35 design. The Sony F5 and F55 share an identical body, including RAW recorder and battery adapter modules. Opposite the operator side are two small optional modules for XLR audio input and timecode/genlock connections. The Canon C100 and C300 share a handgrip, while the C300 and C500 share bodies, handles and LCD/audio input modules.

ARRI’s recent “refresh” of ALEXA creates a new XT line (eXtended Technology) based on the four previous models including M, Plus and Studio. New XT features include a 512GB SSD “XR Module” to record ARRIRAW, ProRes and DNxHD co-developed with London-based Codex, which replaces the current SxS module; a 4:3 CMOS sensor to permit anamorphic capture, which replaces the 16:9 original; an in-camera ND filter module; a rod-based viewfinder bracket; and a quieter fan. Due to ALEXA’s modular design, ARRI says all previous ALEXA’s will accept the XR Module, and most XT features will be available for upgrade as well.

• Initial Super 35 cameras were train wrecks when it came to ergonomics. Now that technical basics have been sorted, ergonomics can take front seat again. We have a century of motion picture camera design to inform and inspire. For instance, the shape and layout of ARRI’s ALEXA lends itself to traditional production, including hand-held. Why? Taking design cues from Alexa are Sony’s new F5 and F55. The sincerest form of flattery.

And while Moore’s Law can shrink and lighten cameras, PL lenses remain hefty. A PL mount effectively dictates a minimum practical camera size. Look down the barrel of a PL-mount lens and notice that RED EPICs, Canon C300s and C500s, and Sony F5 and F55s exemplify this limit — they’re only marginally larger in height and width than the PL-mount itself. Balancing lens-heavy Super 35 cameras remains one of the true challenges in digital cinema camera ergonomics.

• Finding the holy grail of a small, light, clear, super-sharp, universal and affordable electronic viewfinder is certain destiny. RED’s dedicated 1280 x 784 LCOS viewfinder (1000:1 contrast) comes close, as does ARRI’s 1280 x 768 LCOS viewfinder. I haven’t tried RED’s 1280 x 1024 OLED finder (10,000:1 contrast) — OLED produces true blacks, and therefore truer contrast — but Sony’s compact new OLED viewfinder, the DVF-EL100, is spectacular to look into. If only it weren’t $5,000!

On the leeward side of technology are panel-based electronic viewfinders. To me they resemble iPhones, awkward and heavy, especially with battery and HDMI cable attached. They block the operator’s face and obstruct his/her view — not optimal for documentary work. You know who you are, Zacuto, Alphatron, Kinotehnik, Cineroid.

• Now that aerial drones are the stuff of Capitol Hill paranoia, don’t miss Lockheed Martin’s latest flying camera support platforms at NAB: fixed or rotary wing, or lighter than air. What ultra low-budget feature hasn’t dreamed of an aerial crane shot capturing the horizon, or an overhead car tracking shot along the Williamsburg Bridge? (Insurance and FAA issues notwithstanding.) Hint: Sony FS100s with their magnesium frames are remarkably light.

WORKFLOW AND POST

All 64-bit NLEs can edit 4K, and all NLEs, without exception, can edit 4K proxies.

Autodesk Smoke 2013 has now joined the ranks of laptop NLEs, offering a powerful and sophisticated effects toolset tailored to 4K. It costs a bit more upfront, and there’s a learning curve, but you get jaw-dropping image control. And there’s no round tripping between editing and effects. It’s all in one.

Blackmagic Design’s free download of DaVinci Resolve Lite is a windfall to filmmakers around the world. But you’ll need the $995 version to color-correct 4K.

NEW CAMERAS IN 2013

Since my 2012 Filmmaker large-sensor camera round-up, cameras entirely new to the Super 35 scene include Sony’s F5 and F55 (street prices $16,500 and $29,000, body only); Sony’s $3600 APS-C (same as Super 35) NEX-EA50 “wedding camera,” which I profiled in Filmmaker; a high-speed camera from newcomer For-A; and what can only be called the Chinese ALEXA, or is it the Chinese RED?

(Somehow I missed the entry-level C100 in last-year’s round-up, but Canon’s filled-out Cine lineup — C100, C300, C500 and the recently available 1D C — are doing just fine, fast gaining credibility and film credits.)

The For-A FT-ONE is large and beastly, and claims 4K capture up to 900 fps to a pair of internal multi-SSD cartridges, each of which can hold 84 seconds(!). It is the first Super 35 4K PL-mount high-speed camera. (The Phantom 65, also high-speed 4K, uses a 65mm sized sensor requiring Hasselblad lenses.)

I mention the Chinese KineRAW S-35 somewhat tongue-in-cheek. From the spreadsheet and specs I downloaded (mostly Mandarin), you’d have to pay $6,900 to $9,500 in renminbi (current exchange rate) to pre-order one. It seems to record 2K RAW to KineMAG SSDs using Cineform RAW compression, plus 1920 x 1080 at 50p. Listed also are Wi-Fi control and a Cineroid viewfinder. From workflow illustrations, it’s Mac-friendly. Don’t mistake my amused tone for dismissiveness. The LED lighting we enjoy in production is entirely Chinese-made. And they intend to land an unmanned probe on the moon this year. Don’t be surprised if this camera shows up at NAB, if not this year, next.

Maybe this year I should also have included Blackmagic Design’s Cinema Camera, which ignited a firestorm of attention during and after NAB 2012 but has hardly been seen since. B&H lists the EF-mount and MFT models as back-ordered and available for pre-order. However, it’s not Super 35 (smaller, odd-sized industrial sensor), and I have yet to actually see one in the street. Or anywhere, for that matter. Maybe I’ll have something to say about it next year.

Panasonic’s booth at last year’s NAB showed under glass a balsacam Super 35 4K modular camera. (Balsacam is an industry technical term derived from the lightweight wood). In size and configuration, it looked somewhat like Sony’s F5/55 system. Panasonic spokesperson Joe Facchini at the time said the real thing would come “sometime next year.” No indication at the time of this writing whether or not this will be the case.

And RED this year? Stirred more waves with litigation than innovation. Never a pretty sight.

One last new item to mention, which seems to embody a number of industry trends, for better or worse: Convergent Design just announced their Odyssey 7 “monitor/recorder product,” scheduled to ship July-August. Their terminology reflects an ambiguity. At a glance, it’s a 7.7-inch 1280 x 800 pixel OLED monitor for $1,295. That’s remarkable, as Sony’s excellent PMV-741 7.4-inch 960 x 540 OLED monitor retails for a $1,000 more. If you’ve invested in a Super 35 camera and lenses, you want to see fine detail and true blacks!

Even more remarkable: standard functions include waveform, zebras, a histogram, vectorscope, focus assist, 1:1 pixel mode, false color, timecode display and audio level. I/O includes HDMI 1.4a (the one that supports Ultra HD) and SDI for SD/HD/3G in both single and dual link. A Bluetooth iPhone/Android app brings remote control. For a thousand dollars more, a 7Q version adds inputs for four simultaneous recordings with live switching and a quad-split display.

“And that’s not all!” I can hear the NAB barker projecting above the crowd.

Odyssey 7 also features dual slots for 2.5-inch SSDs. Although, when you buy an Odyssey 7, you’re getting a monitor only. The SSD slots are inert.

Here’s the hitch: Convergent Design will operate an online store from which you rent access to codecs on a 24-hour basis, or buy them outright, turning your Odyssey into a small, agile, powerful recorder for your Super 35 camera. When active, SSDs in sizes of 240/480/960 GB can capture 500 Mbytes/sec, either solo, in series (spanning), in RAID 0 for 1000 Mbytes/sec, or RAID 1 for mirroring (instant backup). These are impressive specs. DNxHD will not be rented, only sold. (Other popular codecs will likely be added.) ARRIRAW and Canon RAW will be rented as well as sold. To buy them outright will probably multiply the cost of the Odyssey 7. The 7Q will add the ability to record 4K via four HD-SDI camera inputs. This won’t be free either.

Away from the Internet or misplaced your credit card? You’re out of luck.

At least you’ll see pretty pictures.