Back to selection

Back to selection

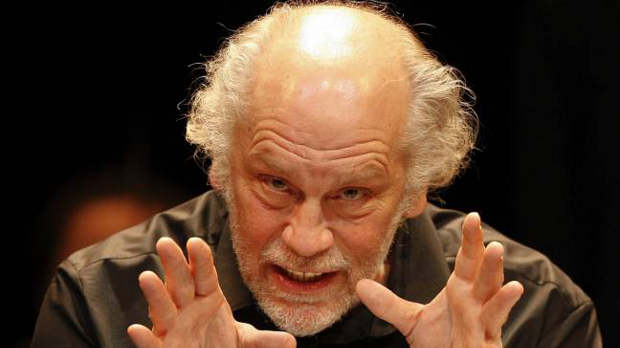

John Malkovich: a Figure in Someone Else’s Dream

Last weekend, John Malkovich came to Toronto to play Casanova onstage in The Giacomo Variations. The lanky 59-year-old made local headlines when he aided a fellow guest at his hotel who gashed his neck on some sharp scaffolding. Malkovich wondered if the next time the fellow saw him on screen, “He may think, ‘This guy had his hands around my neck.’”

Malkovich was speaking to a capacity audience at the TIFF Bell Lightbox. He appeared between performances to kick off TIFF’s summer program that was sharing space with the Century of Chinese Cinema program featuring the likes of Chris Doyle and Chen Kaige. As one of the greatest actors in the world, Malkovich compared performing on stage and on screen.

Theatre acting is like painting where the artist constantly changes his brushstrokes like an actor adjusts his delivery and reactions over several performances. In contrast, film acting is like a line drawing whereby the artist does not revise what he has already committed to paper. Under the guidance of a director, Malkovich said, “You say it’s beyond [your] control, and you do that one day. You never go back and look at it.” There isn’t enough time, and so the actor surrenders control to the director. “In theatre, you decide the rhythmn, the musicality, and what is emotional and not. In a movie that is decided for you.” Malkovich feels that directors manipulate actors far more before a camera than on a stage. “You are a figure in someone else’s dream. So they say, ‘Go over there,’ you go over there.”

Malkovich admitted that he “drove nuts” Stephen Frears, who directed him in 1988’s Dangerous Liaisions, “but to be fair he had somewhat the same effect on me.” Malkovich recalls Frears first approaching him about the film after seeing him perform in Burn This on Broadway in 1987. Frears came backstage and diplomatically asked Malkovich, “Tell me. Why is it that you’re actually never very good in the cinema?” Malkovich answered that he didn’t control his performances. “So,” said Frears, “you’ll have to be controlled.”

On set, Malkovich challenged Frears about certain blocking and shots, so Frears retaliated by forcing his headstrong actor to view his own choices. “Stephen used to send me to watch the dailies when I’d rather spend my evenings drinking,” Malkovich deadpanned, keeping the TIFF audience in stitches. Quite often Frears was right, and Malkovich accepted this on a philosophical note: “The camera likes what it likes, and you are always the servant to that master.”

Malkovich stated that he prefers no particular directorial style and doesn’t mind being directed. He even adored Luc Besson in 1999’s Joan of Arc who committed the cardinal sin of delivering line readings — and Besson didn’t even speak English at the time. “I’m not very good at that,” said Malkovich about line readings, “but I kind of liked that.”

That wasn’t the case on Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Sheltering Sky. “I’d gotten hepatitis in north Africa so I got quite crabby.” To make things worse, Malkovich didn’t get along with one of the producers. However, he found the Italian director light-hearted and funny. Not so with Woody Allen: “Obviously funny, but you’d never hear laughter on his set. He’s unbelievably serious.” No surprise that Malkovich disagrees with Hitchcock’s edict that “actors are cattle.” “I think that’s unproductive. I like to have an idea of what we’re trying to make, because I may be helpful.”

Malkovich’s contribution was enormous on Being John Malkovich. After reading only the first 20 pages he knew Charlie Kaufman was “an amazing writer.” However, Malkovich wouldn’t star in the title role, though he wished to direct another star, someone like William Hurt, Sean Penn or even William Shatner. (As the TIFF audience roared with laughter, Malkovich reconsidered the last suggestion: “That would put it in a different genre.”) Regardless, Malkovich wouldn’t direct a film that had his own name in the title. “I’m not insane.”

Flash forward a few years to France where Malkovich was living. His manager asked him to meet a young director named Spike Jonze to talk about the script. They were chatting at a Paris hotel for 30 minutes when Malkovich stopped and asked the kid, “Are you American?” First-time feature-film director Jonze was born in Maryland. “I thought he was Czech, because of the way he talked.” Jonze either answered him with, That’s harsh (meaning yes), or That’s okay, maybe (meaning no). “I really thought he was a foreigner,” Malkovich recalled in all sincerity. “I couldn’t really grasp it, but I liked him immensely.”

The kid and Malkovich went on to make the brilliant comedy, disagreeing on casting only once. After Kevin Bacon declined to play Malkovich’s best friend, the actor wanted Charlie Sheen who, of course, Malkovich never met. So, why did he insist on Sheen? “If you’re in an existential crisis about a coven of lesbian witches you want that person who’s gonna say, ‘Hey, give me their number when you’re through.’”

Malkovich summed up his film work graciously: “I have great sympathy for directors. It’s a hard job. They don’t know what’s going to happen. They have a ton of pressure. They’re spending enormous sums, even on a little independent film.” Within minutes Malkovich dashed back to the theatre.