Back to selection

Back to selection

Leading the Way in Non-Traditional Distribution: Jonathan Goodman Levitt’s Follow the Leader

Follow the Leader

Follow the Leader Jonathan Goodman Levitt’s Follow the Leader may have recently won the Jury Prize in the Feature Film Competition at the 2013 Northside Festival in Brooklyn, but its DIY distinction lies far beyond what’s captured in front of the lens. Over the course of three years, Levitt’s doc trails a trio of high school class presidents (and aspiring U.S. presidents) – all male and all hailing from one of the original 13 Colonies (Virginia, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania). Even more remarkable than these teenagers’ evolving attitudes, though, is the director’s distribution game plan, deployed with the targeted precision of a political campaign. Filmmaker spoke with Levitt about everything from his outside the box, multi-platform strategy, which includes the live event, Follow the Leader: Reality Check Interactive, to choosing the Democratic and Republican National Conventions to stage his world premieres.

Filmmaker: So how did the film, and its three-character structure, originate? How did you select the – initially conservative teenage male – protagonists that the doc focuses on?

Levitt: I was living and working in London for about a decade, including a couple of years before 9/11 and several years after. The summer after 9/11, while I was teaching in New Jersey at the Governor’s School held at Monmouth University, I was first struck that the student leaders that year had simply changed dramatically compared to students I’d taught prior to 9/11. That’s not surprising on its face, but coming from abroad it was shocking and made me feel like kids growing up here in the wake of 9/11, and just people generally in the U.S., were getting a radically different look at current events compared to those of us living elsewhere. That’s still an idea that many Americans are resistant to considering, but that idea and its impact preoccupied me when I was considering moving back home.

I wanted my first project here to be about what it meant for those who’d come of age during such a trying time for our country – about what being American meant to them, in part so I could better understand what had happened to our collective psyche while I was away. I also saw that public opinion, and even the news itself, were beginning to shift somewhat here; and I wanted to experience that shift through the eyes of those who were at the same time going through the even more revelatory experience of growing up and learning to think for themselves. I didn’t feel that we were adequately contemplating or documenting for posterity the process that the country was going through during these difficult years when a lot of us felt America’s political ideals were in crisis. Also, I thought true-believing youth would offer insights about us all as they became more “enlightened” by age. And I also wanted to begin to ask questions about the war on terror’s legacy as it relates to who will be leading the country a generation from now.

Now, my choice of choosing three initially conservative boys, who essentially represent the traditional leaders of our country, is inherently provocative. It’s not what most documentary viewers – who lean left, like the vast majority of us in the industry do – expect to see in a film about “future leaders.” But what I was trying to do was reflect the actual politics of our country, which is still run in the large majority by relatively privileged white men. I mean, when President Obama took office, there wasn’t a single African-American senator remaining in Congress. And most of us don’t know that because we’re prone to focusing on the aspirations we want to achieve rather than examining the reality – which we need to do more of if we’re going to change it. So, we’re trying to provoke, frankly in part through outrage, a new kind of discussion that considers political realities. At the same time, I also wanted to bring new audiences, namely conservatives and traditionalists whose views are fairly represented and not demonized within the film, into the sort of “documentary conversation” that typically attracts mostly progressives. These are difficult conversations for us to have as Americans, and too often we find ourselves as filmmakers preaching to the converted – and then wondering why it’s next to impossible to move the other half of the country.

So from 2005 through 2006, I searched for “characters” whose politics I didn’t quite understand, but whom I liked personally – and in whom I sensed changes afoot. Yes, I do a lot of research for a longitudinal film, because I knew I’d be essentially tied to the characters for a long time. In the end, we filmed for over three years, and the reflective interviews with the boys were one and two years after that. Why three boys and not less, apart from the fact that I’m a glutton for punishment? First, three characters feels like something of a limit to me if you’re trying to tell their separate stories intimately in the space of one feature. But why I didn’t just choose three interconnected stories, say three kids from the same school, was more of a formal challenge to myself to make a film with three equally weighted stories? I’d tried it once before on my film Sunny Intervals and Showers, and I wound up essentially demoting two of the three characters I followed into minor roles in favor of the eventual central character of the film.

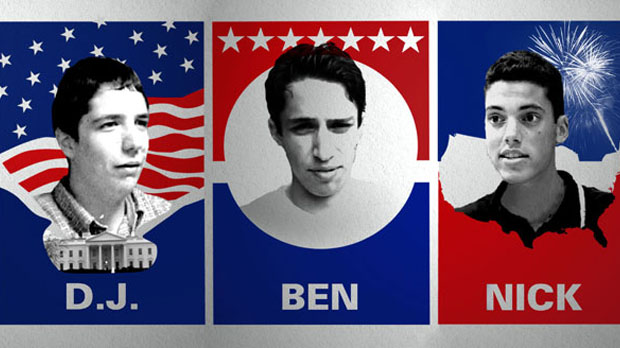

From there it was casting not unlike a fiction film. You want characters who serve different purposes within the film, yet feel like they belong in the same film. And I started going to schools and “leadership training” programs and met a few thousand kids. D.J. is the naturally charismatic political operator whose playfulness and, some might say, dorkiness make him not really look the part of a politician; and he brings the religious streak that’s important within American politics. Ben is a loyal party man who lays out a stark vision of climbing the political ladder one rung at a time, while his parents are also beginning to go through a divorce – which makes him immediately relatable. And Nick is the all-American boy who everyone in town has high hopes for, and who from the start seems to channel many of the attitudes prevalent among the millennial generation.

Filmmaker: Follow the Leader has the unusual distinction of having had its world premieres at both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions last year. Why did you decide to take this approach?

Levitt: Well, there are two ways I’d like to answer that. The first is by repeating something I repeated to myself after an influential discussion with the brilliant Katy Chevigny, one of the founders of Arts Engine. I was a bit out of sorts while struggling to complete the film, yet trying to simultaneously jumpstart the distribution quickly, and she said, “Stunts work.” I took that advice to heart, and tried to come up with an idea in the wake of our successful Kickstarter campaign to raise completion funds in July 2012. The country was in the heat of the presidential campaign and the conventions were less than a month away, and I kept waking up thinking that it would amazing if we could show the film at both the RNC and DNC. Screening at both conventions would also make a clear statement that the film itself wasn’t pushing a political agenda, in spite of both sides’ suspicions to the contrary. I was interviewed on Fox a few weeks out from the RNC (which was the week before the DNC), and mentioned the idea on air. And saying so publicly somehow made it materialize, though not without a lot of work on very short notice among our micro team!

The second way I’d put it is less triumphant. I’d made what in hindsight was the mistake of submitting the film to several top festivals before it was done, with the idea that we’d get into one – and then be able to raise a limited amount of completion funds more easily. All we got was a stack of rejections that led to the Kickstarter campaign, and a decision to forgo traditional order-of-distribution windowing altogether. We let the film be broadcast right away internationally where there was more initial interest given its nonjudgmental style, and decided to experiment with an almost backwards-order distribution strategy. I mean, it comes out theatrically this fall – after it’s been released not only digitally, but also on TV in most major markets. If I had it to do over again, I don’t know if I would do things differently. It would have been hard to resist the dream of a traditional and very wide distribution that comes with enthusiasm that we had (to consider the film rather than premiere it) from programmers at Sundance, Berlin, LAFF and elsewhere. Yet if I knew we were going to be rejected as we were, I would have submitted to a wider range of festivals far earlier on, and tried to get Follow the Leader out widely nationally, digitally and on TV, earlier than we did.

Filmmaker: Could you discuss your Tugg distribution plan and why you chose to go the crowdsourcing route? Is this the future for indies that want theatrical?

Levitt: We’re excited to be working with Tugg – and everyone there, from the first time I met Pablo Gonzalez at Film Week last year, has been an absolute pleasure to work with in getting the film up and running on their platform. But I take issue with the idea that Tugg is somehow more important to our distribution strategy than our digital release via Cinedigm on iTunes, Amazon, Playstation and Xbox; or our public television broadcasts on PBS timed to the Fourth of July and the 9/11 anniversary; or one-off and week-long traditional theatrical runs, like at the Angelika Film Center in Fairfax, Virginia, September 6-12. Or the ongoing college and community tour that Changeworx has been organizing with our outreach partners, or our interactive work with Reality Check. That said, we’re not just throwing different things at a wall to see what sticks. It’s just become clear that different elements of what we’re doing work better for different audiences. For a school club or community organization that doesn’t want to go through us directly, and wants to see the film at their local AMC, Cinemark or Regal Cinema, Tugg presents an incredible opportunity. We don’t expect the screenings to bring in much money, but it’s very low risk and has amazing potential to help news of the film spread via word of mouth in communities to which we might not have direct access.

As to your question about whether crowdsourcing for theatrical – or fundraising like Kickstarter or Indiegogo for that matter – is the future: Such statements are vastly overblown to me. For filmmakers, these are important new tools that are here to stay, which are especially good for publicizing unknown work, building relationships with audiences, and in the case of Tugg having an “easy in” to theaters. But it’s only a minority of films and filmmakers, often because of some degree of a celebrity element, who are able to make crowdsourcing viable as an overall answer rather than a tool. People who haven’t been in the industry long, or who view these things from the outside, should consider that crowdsourcing and crowdfunding are partly answers to deficiencies and recent changes in funding and distribution. It’s more complicated and less lucrative to be a filmmaker today for most of us making long-form docs, particularly when it comes to reduced opportunities for financing and airing independent one-off documentaries via television.

Filmmaker: How do your Reality Check interactive events work?

Levitt: Reality Check breaks the feature documentary Follow the Leader into five discrete “episodes” that chart the boys’ coming-of-age stories, and that – in the RCI presentation – alternate with collective, facilitated interactive keypad voting sections. What we’re doing is leading viewers – who we consider participants – through a journey that allows for deeper engagement, and usually greater fulfillment. All responses (to questions about the characters, their views, participants’ own political views and current events) are reported in real-time, split along demographic lines. So everyone gets a “reality check” about what people really think in relation to what they’re watching, which complements and highlights their own unique reactions. The idea itself came out of work-in-progress screenings of the film, which showed us how differently people reacted to the film given their own political ideologies. We wanted to find a way to make the great diversity of these highly personal responses part of the experience for everyone watching. We premiered the event to great success at the Paley Center for Media last October, on the night of the memorable second presidential debate.

Put another way, what we’re trying to create is really an ideal viewing and learning experience for the film, as well as an argument for why people should come out and see it live in a theater. Young people are a core audience for us, and they’re even more open to new modes of storytelling and a viewing experience that promises something different and unpredictable. What we’re doing is turning viewers into active participants who each complete the film for themselves as they watch. It’s new in this context, but in art in general that’s not a new idea at all. We’re just explicit about how every person who sees the film is seeing a different film because of what they bring to it. What we want people to do is play this idea out in a wider political context: What do we experience when we watch the news or a politician giving a speech? Is each of us really even “seeing” the same thing?

Right now, Reality Check has been touring some as a live event, and it receives off-the-chart ratings from participants – but it’s often cost-prohibitive to put on for groups that want to host it. For far wider exposure, we’re building a way to experience Reality Check: Follow the Leader Interactive online and make it available on-demand. We’re currently talking with potential funders, broadcasters and online platforms now about making this happen by early next year, so that it can be used to improve the debate leading up to the 2014 mid-term elections.

Filmmaker: What are your ultimate hopes for Follow the Leader and its multi-platform satellites?

Levitt: Follow the Leader is about provoking discussions we need to be having about the political realities and inequalities in our country – in a new way that attracts more of a cross-section of the country politically to participate in the same conversation. And it’s about doing it in a thoughtful and reflective, yet also fun and often amusing, way. I want people to be surprised by the characters at times, and perhaps also by what the characters make them realize and reconsider about their own political views and how they initially formed.

Apart from the inherent pleasure and increased fulfillment from the film experience, we also have serious research questions that we’re looking to investigate through the Reality Check data. For instance, does taking part in the Reality Check Interactive version of Follow the Leader really decrease political polarization, and increase cross-partisan understanding and dialogue? Does Reality Check encourage people to step back and reconsider their political values, or make them vote differently? And does it impact civic participation over time? We’re working with a growing number of academics to make the scientific validity robust. (Research psychology is part of my own background before moving into filmmaking, so it’s not completely out of leftfield.) Rather than simply relying on anecdotal evidence, we’d rather prove that what we’re doing works, or at least know to what extent it doesn’t. It all goes to a central outreach goal, which is basically to encourage a deeper conversation, to change the political conversation for the better. If it goes well, there’s also potential for us to adapt the same format for other films by creating a new type of interactive film version, as both an educational tool or even another option for everyone.