Back to selection

Back to selection

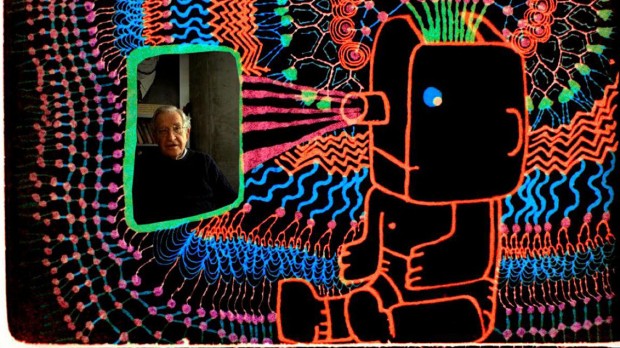

Michel Gondry on Old-School Animation, His Trademark Whimsy, and Plumbing the Mind of Noam Chomsky for Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?

Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy?

Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy? Two highly unique minds converge in Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?, the latest from whimsical visionary Michel Gondry, who aptly subtitles his film, “An Animated Conversation with Noam Chomsky.” In the works for four years, this self-explanatory project from the artist behind Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Dave Chapelle’s Block Party, and a veritable library of music videos is a charming and markedly low-tech doc that literally illustrates the insights of Chomsky, one of the greatest thinkers of our time. Ever-fascinated by the depths of the human brain, and ever-faithful in dressing his films with cartoon-like touches, Gondry presents a curio of a movie that’s unquestionably in his wheelhouse, and that, as the director hopes, may well become a notable piece of Chomsky’s legacy. In a chat that reveals just how open Gondry’s own mind is (not to mention the thickness of his French accent, which he admits is part of a stealth defense tactic), this singular filmmaker talks about using primitive tools like a lightbox and a Bolex camera to craft a film that’s unlike any other this year, and that stands as a symbiotic account of unique brain cells working in tandem.

Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? world premieres tonight at the School of Visual Arts Theater as the closing-night of DOC NYC.

Filmmaker: So I’ll assume you’ve felt a kinship with Noam Chomsky for a long time, given the cerebral and philosophical nature of the work you’ve done.

Gondry: Yes. Especially about creativity, and the sort of democratic aspect of creativity — the idea that creativity can be found in any type of person. And I think that’s something we share — this idea that anyone has an interesting point of view and interesting things to say and share with the world, even if we don’t hear their voice.

Filmmaker: I found it interesting that, in the film, you say that you approached this project as “a way to focus [your] often shattered creativity.” Can you elaborate on that a bit?

Gondry: Well, sometimes I’m excited to do several things at once. And the expression I want to make here doesn’t translate well into English, but I’ll say that it felt good to find a project that would take me over the course of four years, with one strong [focus]. That’s what I was trying to say.

Filmmaker: So, by “shattered,” perhaps you also mean “scattered?”

Gondry: Maybe! [Laughs] Maybe I used the wrong word. “Shattered” would mean it all sort of exploded.

Filmmaker: You’re very self-deprecating in the film, and there are parts where you express fears of looking stupid when speaking to Chomsky. Were you extremely intimidated by him throughout this process? There’s a lot of humility there.

Gondry: Well, I was, but I also wanted to make sure these parts were entertaining. It was a way to keep it light. So it was sort of self-deprecating, but I know that most people would feel this same way. So it’s an honest point of view, but also, sometimes it’s just hard to follow him, and sometimes he was sort of dismissive. So I thought it was funny [to include that humility], and I have an excuse, which is the fact that I’m not very skilled in English. And I use that a lot to justify my lack of knowledge. [Laughs] For instance, I would not have been so at ease with a French scientist, maybe.

Filmmaker: My favorite part of the film was when you mentioned how we’re taught symbols before seeing things in real life. It didn’t quite translate the way you wanted it to with Chomsky, but I have an art background, and one of the key lessons I was taught was to draw what you see, not what you think you know.

Gondry: I had this advice, too, when I was learning how to draw. People were telling me to draw from nature, not from photos, or illustrations, or your imagination. Go out in nature and draw what you see. And it was funny because [in the film] it was just an observation I was making, and Noam said, “No, it’s wrong!” [Laughs] Because he wanted to tie it to the idea of psychic continuity. But what I was trying to say was just a basic concept. When you’re a kid, you have a filtered approach to the world. I was not saying something that could be right or wrong, it was just an observation.

Filmmaker: Well, piggybacking on the idea of dropping preconceptions and drawing what you see, this film was a very organic process. Obviously, you didn’t know what was going to come of your interview with Chomsky, so in terms of the art, you needed to just create with whatever surprises you gleaned from the conversation.

Gondry: Well it’s a principle of the documentary. I think if you go out to do interviews with the answer in mind, you’re going to bias the whole process. Sometimes it happens with people who conduct interviews. They want you to tell them what they want to hear, so they’re going to force you, and corner you, and bend you on purpose. So it was very important for me to start this project with no specific result in mind. I did haver some ideas — the idea to illustrate to illustrate, and have abstract drawing, was already there. I didn’t know where the conversation would go, and how I would illustrate that, but the idea of abstraction was already in my mind. It was very practical and handy for me. When I was not necessarily understanding everything he was saying exactly, I could just present it in abstraction. And then I would not betray anything that he was saying. I’d keep a certain [amount] of abstraction, so people can understand it all on their own levels. And some of the audience can understand more than I did, which is fine by me. I love that people have their own levels of understanding.

Filmmaker: Can you discuss the actual technique that you used to achieve the actual look that you did? How you created these animations?

Gondry: It’s very simple. I had a light box, and I used animation paper, and I drew with Sharpies, which are very bright and sort of diffuse into the paper. So that gives a very nice texture. And the paper is very thin, so, with the light coming through from underneath, you can use a picture like I used, printed out from my printer, and use the picture in negative. So if I wanted a finer result, I could switch back to positive, so the background would be positive and the drawing would be negative. So it was sort of like post-production, but it was all before the shooting. And I shot it all with my 16mm mechanical Bolex. So it’s on film, and it’s something over which I had full control. It’s a setup I can put in a very small room, or even in my closet in Los Angeles, and I can do it everywhere I go — in New York, Paris. So I could continue the work wherever I was. I could do some of the animation on a small light box that I could carry with me.

Filmmaker: Yeah, I was going to ask you about the size of the light box, and if it was easily portable.

Gondry: Yeah, I have a smaller one to travel with. It’s very portable — a very simple setup. It’s the same setup you have when you’re an animator, only I had to put the camera on the top.

Filmmaker: So there’s no computer enhancement whatsoever?

Gondry: No. If I used computers, I’d have to have people help me, and then it’s not as personal.

Filmmaker: You’ve always had some animated proclivities, and there’s a whimsy in your work that’s akin to animation, even though it’s typically live-action. Were you actively looking for a project that could fully employ your animation-like tendencies?

Gondry: Yes! And I’m still hoping I will do another one that’s fully animated, and more fictional. I think it’s a very truthful way to express your thoughts, because the process is very direct. That’s what I’ve always liked about animation, particularly abstract animation. You go from the idea to execution, straight from your brain. It’s like when you hear someone playing an instrument, and you feel the direct connection between the instrument and his brain, because the instrument becomes an extension of his arms and fingers. It’s like a scanner of the brain and thought process that you can watch, or hear. This type of abstract animation is very intimate in that way.

Filmmaker: I actually just returned from the Baja Film Festival in Los Cabos, where they screened The Science of Sleep as part of a tribute to Gael Garcia Bernal. How does the process of making something like that, which is also very whimsical and cerebral, compare to making a project like this?

Gondry: Well, with The Science of Sleep, for instance, initially I wanted the dream world to be as realistic as real life, but since it was involving catastrophes and bigger and bigger events, we couldn’t fund it. So I decided to use animation just to make it affordable. And, of course, I was aware that it would give it a stronger texture and different style. But the whimsy that you’re talking about comes, sometimes, from making something affordable, or from being the best way to illustrate something I had in mind. It’s not that I’m not aware of it. I’m aware of the retrospect of my work. But it’s not like I’m saying, “I’m going to do something whimsical!” It’s more like, “Okay, I’m going to do this idea. And it doesn’t look like a James Cameron film because I don’t have the capacities to achieve that.”

Filmmaker: In Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? you ask Chomsky about his earliest memory, and he mentions being forced to eat oatmeal. What’s your earliest memory?

Gondry: My earliest memory is much later than his. It was when I was three years old, at school. I remember looking back over the middle of the classroom, and trying to make eye contact with the only kid I knew from the year before. I’ve been aware of that memory for a long time.

Filmmaker: And did you make eye contact with the kid?

Gondry: I think so.

Filmmaker: You also mention in the film that your biggest motivator to complete it was being able to show it to Chomsky before he dies, given that he’s 84.

Gondry: Yes, and I was very lucky to have access to his brain for the time that I did. And though he’s certainly made his mark on the world, I wanted to help add to it, and be a part of it.

Filmmaker: You’re only 50 years old, but is there something specific you want to make sure you do before you die?

Gondry: Well I’d like to have a nice girlfriend before I cut it. [Laughs] To not die alone, basically.