Back to selection

Back to selection

The Luxury of Unhappiness: Director Hany Abu-Assad Talks Omar

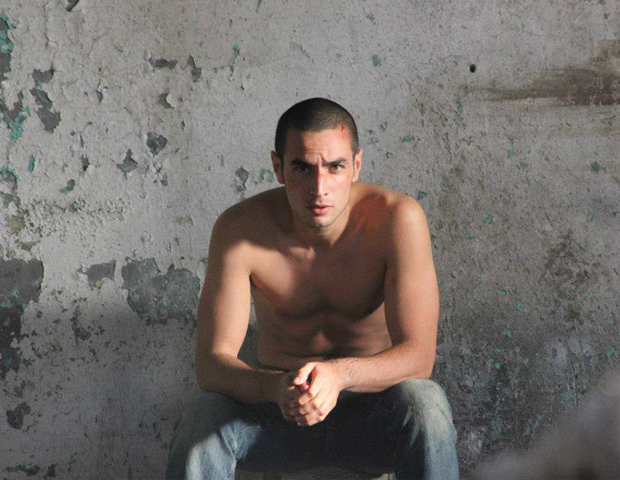

Director Hany Abu-Assad on the set of Omar .

Director Hany Abu-Assad on the set of Omar . In 2002, Palestine made its first Best Foreign Language Film submission to the Academy Awards. Despite accepting films from Puerto Rico, Hong Kong and Taiwan, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences did not accept their submission.

But by the next year, the policy had changed: the Palestinian Ministry of Culture’s submission, Divine Intervention by Elia Suleiman, was accepted. Three years later, Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now, the acclaimed and controversial story of two Palestinian men planning a suicide attack on Tel Aviv, was not only accepted as Palestine’s submission, it was also one of the final five nominees competing for the award at the Oscar ceremony.

Although that year’s statuette went to Gavin Hood’s Tsotsi, the nomination was seen as a coup, not only for Abu-Assad’s personal artistry but also for the cultural autonomy of his homeland.

Now, Abu-Assad has been nominated again: this time for Omar, the taut, deceptively simple tale of a young Palestinian baker (Adam Bakri) drawn into romance with Nadia, a schoolgirl (Elia Suleiman); political violence with Tarek and Amjad, his childhood friends (Eyad Hourani and Samer Bisharatan); and espionage with a Rami, a powerful Israeli agent (Waleed Zuaiter). Omar was an official selection of festivals including New York, Toronto and Cannes, where the film won the Un Certain Regard section’s Jury Prize.

On the eve of Omar‘s theatrical premiere and highly anticipated Oscar run, Abu-Assad sat down with Filmmaker Magazine to discuss how he films kinetic chase scenes, the way in Nazareth compares to L.A. and advice for Oscar voters.

Filmmaker: What brought you to Omar?

Abu-Assad: I was in Los Angeles working on another movie. Suddenly, at four o’clock in the morning, I woke up in a nightmare. I was sweating. I re-read the script and thought, “This is not going to be a good movie.” The combination of the production, the script, everything together gave me this feeling of anxiety. I started thinking, “What is a good movie? What kind of stories do I want to tell?” I panicked.

And then I started to write. At eight in the morning I finished the outline of Omar as it is now.

At the time, I was in an apartment on a small street, near Wilshire and Hauser. Do you know L.A.? Weather-wise, it’s great. But everybody’s unhappy. They’re all unhappy in the good weather.

Filmmaker: How does L.A. compare to Nazareth?

Abu-Assad: In Nazareth, the weather is like L.A. and the people are also unhappy… but in Nazareth, they have a reason. [Laughs] In L.A., everybody has higher expectations than they can reach. Not because they’re not talented; I assume we’re all talented. It’s about luck. It’s like a casino: one winner and the others will be upset, lose a lot of money. In L.A., we all live in a big casino where everybody tries their luck. The people are all gambling. One will be so happy and wow, he got the jackpot! The rest? Unhappy. Look at the faces in the casino: exactly the faces in L.A.

Almost everybody is waiting for their moment to come. They are all very sure. And somebody will have his luck, and the celebration of that somebody gives you hope: “See? It can happen!” In L.A., it’s a luxury, unhappiness; expectations are so high. In L.A., people have the luxury of unhappiness.

Filmmaker: Is Palestine like a casino?

Abu-Assad: No. Palestine is surviving. Unhappiness, and people have to survive. People are very, very tense because there are no opportunities at all. At least in L.A., if you can’t make it in the film industry, still you can become a waiter, do valet parking, work in a bank, work in an office. There are lots of opportunities. When I was a student, I cleaned houses and restaurants. Really, I enjoyed it. This was in Holland. One restaurant that I cleaned was Caribbean, one was Middle Eastern, one was a shawarma restaurant.

Filmmaker: Did you get free food?

Abu-Assad: Yeah… and free drinks. As a student, that’s a plus. [laughs] At the time, I was studying to be an airplane engineer.

Filmmaker: Do you miss engineering? What brought you to Holland?

Abu-Assad: No, no, no, I don’t miss it at all. I was born in Nazareth. I was 19 when I went to Holland to study engineering. I finished after six years. I had an uncle living there — and it’s easier to move when you have an uncle in a place; then you at least have a start. If you ask why my uncle was there, he had met a Dutch girl, Janny. When she was 19, she was bored. She didn’t know what to do with her life. A teacher told her, “Go to a kibbutz in Israel; you might enjoy it.”

She wasn’t Jewish, but she went work on a kibbutz in Israel. At that time, there were no checkpoints, nothing. So she went to visit Nazareth — it’s a kind of holy city, well-known. There, she met my uncle. My uncle fell in love with her and she fell in love with him. And that is why, when I wanted to study, I could go to my uncle in Holland.

Funny story: Later, I had a Dutch girlfriend who came with me to Nazareth; a friend of hers, Madeleine, came to visit us. During her trip, she met my brother. Now my brother and Madeleine live in Holland and have a daughter named Noor. So: because Janny was bored, Noor was born! [Laughs]

When I finished studying in Holland, I worked as an engineer at a big aerospace company. I worked with machines developing airplane material called “composite.” Light but strong. But it wasn’t right for me. So after two years at the aerospace company, I went back to Palestine. I started to work with my father at his transport company. But I was modern guy, I wanted to modernize the company and make the company better. He didn’t want to bring computers into the company; he thought computers were going to spy on him. He thought with computers, everybody would know what he was doing…

Filmmaker: That’s a legitimate concern. [Laughs]

Abu-Assad: So we had a fight. After the fight, I didn’t know what to do. I left the house, I left the company; I went to Haifa to visit a friend. My friend said, “Let’s go watch a movie.” They were playing a movie by a Western director at the University of Haifa. After the movie was a Q&A with the director and the producer. I told them, “I want to know this work better.” They said, “Come and help us.”

The filmmaker was Rashid Mashcharawi. For one year, I was his assistant. Then I produced his first feature [Curfew]. After that, he produced my first short film. This is how I started to become a filmmaker. So: if my father had agreed to bring modernization to his company, I would still be working with my father. [Laughs]

Filmmaker: It makes sense that you have a background in engineering because many of the scenes in the film seem to involve physics: the shots of Omar scaling the wall with a rope, for instance. Also, the chase scenes through the streets — where Omar weaves in and out of alleys with great energy and speed — have both a physicality and an aerodynamic quality to them.

Abu-Assad: You know what? You are very right. You can see my engineering influence this. I always felt like chase scenes in movies were very boring for a very simple reason: they’re over-covered. You shoot one foot, you shoot this, you shoot that, you make a lot of cuts between all these shots — boom, boom boom, till nothing can be seen anymore. Why are they are cutting so fast? How can I engineer shots where there’s that same energy, shots that convey the urgency of the chase, but where you see what’s going on and without the need for constant cutting? One of the solutions was to make chase scenes through narrow alleys because then you have these walls around and you feel like, “Oh my God!” We shot the chases on locations and in sequence, shot by shot. It’s all real. Those streets are all connected together in real life. Well, there are a few cheats, like the houses that were on the left side… but those streets are almost all connected in real life.

Filmmaker: What kind of a camera did you use?

Abu-Assad: An ALEXA 2K. You know, an old camera. It’s not a special camera for the chase scenes, no. We had to improvise our equipment. As a cameraman, if you’re following Omar from behind, you can really easily run after him with a Steadicam. But if you are in front of him, you can’t run backwards at the same pace that he’s running forwards, for sure not. For that, we built this kind of chair on a small car. Somebody else drags the car while the Steadicam camera operator is sitting on it. And I was constantly like, “Faster! Faster!”

Filmmaker: You didn’t want to film them moving slowly and then speed it up in post-production?

Abu-Assad: No, no, no… I said, “No way!” And then the key grip would say, “No, it’s dangerous!” “I don’t care! Faster!” [Laughs]

Filmmaker: I think new contraptions are frequently created on set. Especially if you’re an engineer, you might think, “Well, this doesn’t exist… but I need it, and I could build it.”

Abu-Assad: Yeah, yeah, yeah! We tried a lot of these things. Like we also made a kind of moving dolly. We found a very small cart that the cameraman could sit on with wheels so you can really go.

There were some shots that were very dangerous. In one scene, Omar walks along a wall, going to see his girlfriend at school. It was actually a very high, narrow wall he was walking on. He climbed up and really if he fell, especially to this side… oh! We had no mattresses. The actor was a brave guy. For some of the jumps, we used a stuntman who had to be wired and later, with special effects, you just take the wires out. But that wall was really dangerous.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about Omar script’s development after your initial four a.m. writing session?

Abu-Assad: The Fourteenth Chick, my first feature film, was written by another writer. Paradise Now was written with two partners. But Omar I did all alone. I asked myself, “What the story that you heard or lived that really grabs you?” I thought of a friend who had been approached by the Secret Service to collaborate. They knew a secret and said, “If we reveal it, you’re fucked.” So he had this conflict about whether to become a traitor or not. At first, he said, “Okay, I will do it,” but did not deliver. This was good drama and it became my starting point. The second thing I thought: “It must be a love story. Omar loves Nadia.” From that, it escalated. We know everything, we know every secret until the end… and then pow, pow, pow!

At eight o’clock in the morning, four hours later, I was like, “Yes, done! This is the structure.” And since then, nothing about the structure changed. Nothing. All the characters were there. It was just fine-tuning.

I was once very paranoid; I thought people were spying on me or there was a bug in my apartment. A friend told me about how the Secret Service tried to make him a collaborator. I took the ending from an article I read in the newspaper. My panic, my need to have a good project, my traumas from the past, stories I experienced, stories I read in the newspaper… they all came together to make Omar alive.

Filmmaker: The project that you abandoned to make Omar, was it someone else’s project?

Abu-Assad: No, I have developed a lot of projects. One with Focus Features, a very good one, but the economics didn’t work. Also I worked on a project with Gianni Noneri — Eleven Minutes, the book by Paulo Coelho — a very good project, I loved it but… I think it would have fallen apart. Economics, also economics, it’s all about economics. How much will it cost us? How much can we sell it for? Is it worth investing in or not? If the numbers are not working, you let it go.

Filmmaker: What was it about this project that made the economics work?

Abu-Assad: Omar? It was very, very cheap, around $2 million. The other projects were too expensive. One was $20 million and the other one was almost $10 million. What makes the budgets so high are the development costs: a million for the book and a million for for executives, for writers, for actors, for unions, for all these people. The development costs of those projects alone were the entire budget for Omar.

Filmmaker: This is the second time you’ve been submitted for Best Foreign Language Film representing Palestine, and again you’re among the five finalists. Does that feel like a big responsibility?

Abu-Assad: It’s pressure. Although this time, I know how it feels — the disappointment. “Oh, I have to go through this again to be disappointed?” The first time, I saw more the winning than the disappointment. Now I see the disappointment more than the winning. Oh that’s bad, always bad. You will be disappointed — and not just me, everybody. A lot of Palestinians are waiting for this moment so that they can be part of the whole community. Recognition is important to them. You know that all this pressure is on you. You know you don’t want to disappoint them. But it doesn’t matter. I am preparing myself for the disappointment. This time, the competition is tough. The other movies, they’re all good.

Filmmaker: Have you seen all of the other nominees?

Abu-Assad: Yes. But the Academy is not the one who should politically recognize Palestine. The United Nations has recognized Palestine as culturally independent and a sovereign nation; this is important. But the Academy has acknowledged that Palestine has the right to submit a movie as an independent culture; that’s it. We are still under occupation. It is not the Academy’s job to make us free. They recognize us as an independent culture, independent people… but many times they have recognized nations that have no state; Hong Kong, for example.

The members who vote are like you and me. I believe most of the members don’t have any kind of political agenda. Their job is recognizing talent and good movies. It’s not about who deserves it and who doesn’t; it’s about quality.

There are some people with a political agenda, sure. Maybe five or 10 percent. It would be unfair to involve your political agenda in your decision. An Oscar is about talent and which is the best film. Appreciating The Godfather and giving it an Oscar doesn’t make you a supporter of organized crime. If a film like The Godfather or Omar is against your ideals, you can still be against organized crime — or against Palestinians — and be fair. I hope the small group of voters with political agendas stay focused on which is the best movie. You have to look at the movie as a movie.