Back to selection

Back to selection

A Band Apart: Crystal Moselle on The Wolfpack

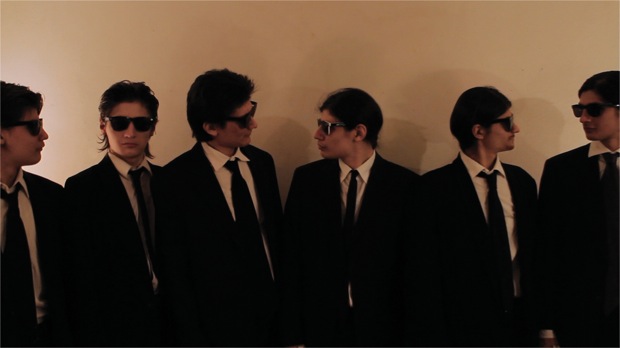

The Wolfpack (Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures)

The Wolfpack (Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures) It’s a stretch of the Lower East Side like any other, with public housing towers looming unostentatiously overhead. One of these is the home of the Angulo brothers — six siblings confined for years (save sporadic supervised walks) to their apartment by their father, Oscar. Crystal Moselle’s first feature The Wolfpack — winner of the Documentary Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival — is the result of an accidental street meeting between the documentarian and her future subjects just as they were starting to regularly go outside in defiance of their dad.

There are obvious questions of abuse and trauma raised by the discovery of a group of children cut off from outside knowledge for years, but Moselle has insisted that she never felt the Angulos were in danger or required intervention on her part once she met and began filming them. Whatever incoherently expressed paranoid fears led him to limit contact with the outside world, Oscar is rarely seen onscreen and no longer in control of his family. The film is substantially constructed from home movies made by the brothers themselves, who provided videos of daily life and reenactments of personal favorites such as Pulp Fiction. These personal archives sit alongside Moselle’s vérité footage of the insularly supportive sibling tribe slowly acclimating to the outside world via experimental first-time group jaunts to the beach and movie theater.

Textural contrasts — between older and newer footage, and between footage captured by Moselle and the Angulos —acknowledge, without particularly clarifying, the multiplicity of viewpoints. Note the gift of the “party time” sequence discussed below, with the brothers dancing wildly with blankets without worrying about outside judgment, indicative of the Angulos’ trust in their in-house reporter but also ambiguously performative. To the extent that they’re comfortable with it, the parents’ viewpoints are also acknowledged: Oscar’s briefly; mother, Susanne’s at greater length as she grows into her own person and reestablishes relationships with the outside world. The shot of her walking away from her husband in an apple orchard, discussed below, is an apt found metaphor.

Like Moselle, Amanda Rose Wilder was a solo shooter on another first feature that took years to complete. Approaching the Elephant tracks a year in the life of a new free school, registering a diverse peer group struggling to peacefully co-exist. Moselle is similarly embedded with her young subjects over a multiyear period. The two sat down to discuss The Wolfpack, the frustrations of first features and urban isolation.

How did you come about this project? I was walking down First Avenue in New York City, and this kid ran past me with long hair, and he just struck my eye. And then, another one ran past me, and another one, and then there were six of them and they all had long hair and they all had the same vibe. I instinctually ran after them. I met up with them at a crosswalk and asked them where they’re from. They said that they were from Delancey Street. I said, “No, there’s no way you’re from Delancey Street. I’ve never seen you around here.” I lived in the East Village at that point, so I felt like I knew everybody. I would’ve seen them around. And then, Govinda asked me, “What is it that you do?” I said, “I’m a filmmaker.” He said, “Oh, we’re interested in getting into the business of filmmaking.” We started looking at cameras together and became friends. It was really about a friendship. I really enjoyed spending time with them and got more and more into their world, and eventually was like, “Hey, I’d love to do some sort of documentary on you guys.” They were game.

So you sought them out as subjects, while at the same time, they sought you out as someone who might teach them filmmaking. They said I was their first friend. And they were obsessively into filmmaking. That’s what they wanted in the future. So, to meet somebody on the street who was into film, immediately, that’s what they wanted. I had a camera around at all times, and would film them taking photos and everything. Four months in I asked them if they wanted to do a documentary. That was after I came to their house for the first time and realized that there was something deeper there.

Did they ever film you? Yeah, actually.

What were your inspirations for Wolfpack? I don’t think that there was a particular inspiration for this film. But during the edit process we watched Harmony Korine’s work. I actually always look to him when I’m feeling down. “Oh, I can’t do this,” or “this isn’t the right way to do something.” He’s an artist who doesn’t give up, doesn’t care about anything besides making his art.

And when you say “anything,” what do you —? He makes what he wants to make, what he feels in his heart is what it should be, not because somebody else is saying, “Oh, it should be like this or like that.”

Did you have people telling you to do things you didn’t want to do? When I was seeking out funding, a lot of people told me that this film was impossible. “How are you going to tell this story? Are these kids likeable?” And I’d say, “What are you talking about? These kids are lovable.” A lot of people pulled me down, and I had to keep fighting to get past that. I think that Harmony Korine inspired me in that way, because I know that he never gave a fuck about what other people said. To me, that’s inspiring. My other job is a commercial director, which is a whole other thing.

As someone who has lived in New York City for seven years, sits in dark theaters to see film after film and dwells in my apartment more than I’d care to say, an interesting part about the film to me was not how their lives veer from the norm but how their lives are actually similar to mine and many people I know. I actually quite related to their interior, oftentimes secluded, way of life. In the film, the mom talks about how she wishes that her children could’ve grown up in the country, so, she says, they could have been outside more. Lack of open space is a reality for all of us who live in the city. It’s a struggle to not be inside all the time. Absolutely.

Do you relate to elements of their life? I do. It’s funny; isolation can be seen in so many different forms. I think somebody sitting and obsessively looking at Facebook is a form of isolation — a social media isolation. After I do a big commercial job. I’ll literally lie on the couch for three days watching movies and letting my mind go to a different world, you know?

Do you have any obsessions? I’m wondering if you’re a “movie junkie,” as the boys are in the film and as Tarantino is, who made their favorite film, Pulp Fiction. I don’t think I’m a movie junkie, but I went to film school and see movies at least two to three times a week, at least once in a theater. In school I studied a lot of avant-garde type of stuff. The first film I worked on was called Excavating Taylor Mead. It was about a Warhol superstar beat poet who is a big part of that film scene. He’s in the movies Lemon Hearts and The Flower Thief. I think I have a little bit of a YouTube obsession. I watch strange, weird videos about real people.

I’m curious about when you found out about the footage the boys filmed of themselves, and when you chose to use it in your film. All the way through, it seems, there is footage incorporated that they shot. They would bring me presents, and it was always footage. They’d make films, and it was about a year and a half into the process when they gave me the VHS tapes with all the footage from their childhood. It was pretty amazing. That’s when you’re like, “Oh, I think I do have a documentary. I think something’s here.”

Did they give it to you as a gift with the thought that you would use it to make a film about them? Yes. At one point, Mukunda was talking to his brother and he was like, “Well, during party time…” I asked him, “What’s party time?” And he goes, “Oh, it’s, you know, it’s just this thing that me and my brothers do. It’s a private thing.” And I said, “Okay. I’d love to see it sometime. Can I come over for party time?” And he said, “Nah, nah, you can’t. Sorry.” And then, one day, I came over, and he gave me a little card because I’d given them a camera to have at home to film with. He said, “Oh, here you go.” I said, “What’s this?” He goes, “It’s party time.”

Could you talk a little bit about the music in the film, how you chose to use it and why? It’s not your typical ambient documentary music. My editor, Enat Sidi, she is a musical genius. I told her that she should do a musical film. We came up with this idea that we wanted the sound to incorporate a metal vibe but still have a nostalgic, atmospheric, not too pointy feel. I didn’t want it to be too obvious or make the drama heightened. We worked really hard on that composition for months to get it right. I think it’s perfect. I love it.

Can you talk a little bit about your relationship with the boys’ mom and dad? When I first started going to their house, the parents were never there. I think Thanksgiving was when I first met them. The mom was so wonderful. I mean, she’s had such a beautiful transformation through the process of the film, and it’s still happening. We’re good friends. And the dad, you know, Oscar and I are cool. He’s very Zen about the whole situation. He just let it be what it was.

I love the shot of the mom at the end of the film, the wide shot in the apple orchard when she breaks off and walks another way from him. Can you believe we got that? That was like, documentary dreams being made there. Enat was like, “That is some realism right there. I don’t even know what it’s about, but that is some realism.” [Laughs]

How do you think the films the boys chose to reenact and how they chose to reenact them speak to who they were? Well, they were stuck in the house. They weren’t empowered. So, I think when they were playing roles where they’re empowered, that made them feel like they had some sort of power. And adolescent boys, little boys want to play with guns and they want to be cool. So, playing gangsters and bad asses, from Tarantino’s films, it made them feel like they were living that. One of my favorite parts is that cross of what is real and what isn’t. Such as when the police are mistaken and think that they have real guns, and they’re like, “Oh, man. Little genius film school kids who make beautiful [fake] guns.”

The boys seemed inhibited in a lot of ways, but in some ways very uninhibited. They are strikingly open people in front of your camera. Well, they were determined. Their dad was scared of the outside world, but they weren’t. That’s why it was so crazy. The minute those gates were open, they were like, more determined than ever, than your average person, you know? The fears of, “Oh, you can’t make this happen in your life” weren’t there. If anything, their father heightened their idea that anything was possible.

That’s what I gathered, that to their dad it was either be isolated or famous. Yes. And it’s happening.

The destiny he envisioned. It’s strange. But they’re taking it very well. They’re very grateful and appreciative of what’s happening. They want to make movies. This is helping them in some sense, you know what I mean?

Can you walk me through how you shot the film, who your crew was? Well, I shot it myself, as you can probably tell. [Laughs] It was intimidating.

Did you have a sound person? Sometimes.

Do you feel like working as a solo shooter helped you get your story? Yes. After a while, I would sometimes have other people come in or bring other people. But generally, it was just me. I didn’t start doing interviews until about two years in. I’d done a couple of them with Govinda and Mukunda. But, I didn’t interview the dad until two years into the film. So, it was a slow process.

Do you think about the boys as co-directors? What, to you, was their role in the making of this film? Did they have a role in the editing? No, no, no. Absolutely not. No, they didn’t see anything until it was finished. I think that they would know something needed to be filmed, and they’d film it for me if I wasn’t there. So, it was collaborative in that sense. I think that they wanted the film to happen. They all had expressed to me that it felt like it was the truth of who they are, that they didn’t feel like there were any judgments or that I was tweaking anything in a way that wasn’t there. I always just like to add that the boys are brilliant and creative and wonderful people.

Do you get people saying they are not? No. I’m just their cheerleader, their weird auntie. They’re doing great, too. They’re following their path. Bhagavan, the oldest one, he’s in this hip-hop dance theater group, and he’s so content. I said to him, “Do you want me to hook you up with some people I know in the dance world, people who have danced with pop stars and all of that?” And he said, “Oh, no, I don’t want to do that. I love what I do. I’m very content.” Wow, that’s amazing.

Are his parents at the same place? Yeah, they all live there together still. Govinda left. Everybody else lives there.

And are they still home schooling? I think it’s Jagadisa’s last year, and then everybody will be out. And where did your film play?

Approaching the Elephant premiered at True/False. And then it played Maryland, Sarasota, BAMcinemaFest, CPH:DOX, Rotterdam, others. Cool. How was the ride?

Fantastic. It’s been a year of more traveling than I would ever, ever do because I don’t have any money. Oh, god. I do commercials. And I’ve gotta go fight for my film, but it’s terrifying. I’ll be broke. I mean, I lived on a couch for a year, the last year, finishing the film. I’d been working nonstop before that. I just like, let go of everything.

Can you imagine making another film the same way? I would raise money earlier. I was balancing the film and trying to work at the same time, and it was really difficult on me; it stressed me out. I didn’t sleep for, like, a year. Anything else? There’s so many things. I learned so much during this process about shooting, about building a scene.

How did you learn how to build a scene? Getting into that edit with Enat. She schooled me on a lot.

How did you work with Enat? She edited and I would sit next to her and be a part of it. We absolutely worked together. But she was pushing the buttons and building the sequences. I mean, I think with the first edit, I was exploring the footage that I had and what kind of story I had and started getting a handle on what we had. Quite a few editors signed on and then they didn’t want to do it after watching the footage, it was too overwhelming. It was a really hard edit.

Why? I think a lot of the early stuff, I didn’t have a plan, so it was just me hanging out with these kids fooling around, not shooting scenes. I was like, “Oh, I’m hanging out with these kids, we make films together.” I wasn’t really thinking back then that I was going to do a documentary. I was just like, “Oh, it would be cool. I don’t know.” I wasn’t, committing, imagining it as a scene later. So, yeah, I learned a lot about that stuff later.