Back to selection

Back to selection

Act Naturally

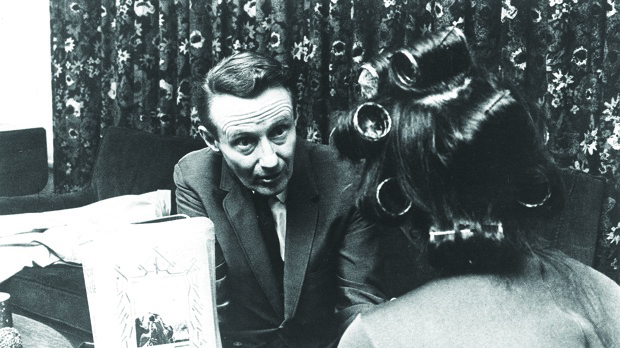

Paul Brennan in Salesman (Photo courtesy of the Criterion Collection)

Paul Brennan in Salesman (Photo courtesy of the Criterion Collection) “Giving the movie its comic and poignant dimension is Brennan’s performance as Brennan.” In the wake of Albert Maysles’ death in March, I returned to this intriguing reference to “performance” in Vincent Canby’s 1969 review of Salesman, Albert and David Maysles’ landmark work of direct cinema. Canby was, of course, referring to Paul Brennan, affectionately known as “The Badger.” Brennan’s performance — if we can call it that — is indeed astonishing. A man of unremarkable looks, he holds the screen with an enthralling intensity. Of course, Brennan isn’t an actor but rather a “real person,” a documentary subject of the most prosaic sort: a Bible salesman.

Canby’s characterization can be read as a literal observation that Brennan is, by trade, a performer. To his unwitting, lower-income customers — his audience — he is an indefatigable and ever-cheerful salesman, pushing products they don’t want and can’t afford. It’s a job and an act — a job that requires acting, but Brennan’s bluster and blarney fail to conceal a creeping, crippling self-doubt. In a series of motel-room interludes, from Boston to Miami, Brennan confides to his colleagues, and the filmmakers, that he is struggling and failing to do his job. Inexorably, the distance between the two Brennans widens, and the film reaches its tragic and devastating conclusion.

The power of the film resides in Brennan’s willingness to offer both sides of himself to the Maysles’ camera. This exhibitionism was stunning in 1969, and it still shocks today — a sneakily subversive portrait of the underside of the American dream and the commodification of faith. What Canby seems to recognize — rightly, I think — is that Brennan’s relationship to the Maysles could also accurately be described as a performance: not enacted exclusively for the camera, but ever conscious of it.

Granted, the filmmakers are less overtly present in the frame than they were later — certainly than in Gimme Shelter and Grey Gardens, and the recent Iris, in which Albert himself appears on screen a handful of times. Re-watching the film, I detected only the faintest trace of the Maysles onscreen: a light stand in the room during the Chicago sales conference scene, in which “theological consultant” Melbourne I. Feltman exhorts Brennan and his fellow salesmen with a missionary zeal to do “the Father’s business.” In a film of intimate spaces, of humble private homes and roadside motels, Brennan would certainly have been aware of the whirring 16mm camera on Albert’s shoulder and the microphone in David’s hand. Yet their physical presence is unacknowledged.

While watching the film, I was thinking about Joshua Oppenheimer, who issued a recent manifesto-of-sorts during a talk at the 2015 True/False Film Festival, in which he asserted: “All documentaries are performance. They are performance precisely where people are playing themselves.” Regarding direct cinema, he claimed: “In so-called ‘fly-on-the-wall’ documentary, there’s a claim that the camera is a transparent window onto a pre-existing reality. But what really is happening is that the director and the film crew and the subjects are collaborating to simulate a reality in which they pretend the camera is not present. It’s a kind of dishonest story about how the film was made that performs a useful function — namely it helps us to suspend our disbelief and perceive that simulation as reality.”

Have we as documentarians — or at least those of us influenced by the Maysles and the tradition of direct cinema — been guarding a secret? If so, it’s been hiding in plain sight. As Albert himself pointed out in his own website manifesto, “It’s not ‘fly-on-the-wall.’ That would be mindless. You need to establish rapport even without saying so but through eye contact and empathy.” Canby’s insistence on drawing attention to Brennan’s performance suggests we haven’t always been telling ourselves a dishonest story. After all, Canby wasn’t an obscure film theorist — he was the chief film critic for the most influential newspaper in America. For him, the truths on display in Salesman weren’t undermined by the recognition that Brennan was engaged in a “performance” or what Albert called “rapport.” Canby called it a “fine, pure picture.”

Brennan wasn’t invited into the Maysles’ edit room and filmed, as Mick Jagger was in Gimme Shelter, to remind us that he was complicit with the filmmakers in staging this particular, rather painful, reality. He didn’t need to: A reflexive process isn’t a badge of honesty, and it certainly didn’t stop Pauline Kael from claiming that Gimme Shelter was guilty of “disingenuous movie-making.” It’s notable that Kael also claimed, erroneously, that Brennan was a roofing-and-siding salesman who’d been recruited and cast by the Maysles — a charge they refuted. In fact, he went on to be a roofing-and-siding salesman after he got out of the Bible business.

Many years ago, in tribute, a friend cast Brennan in a small role in his graduate film school thesis, a fiction film about a traveling salesman. He was shocked that Brennan accepted the role and further surprised that the man who showed up was just like the man in Salesman. Why wouldn’t he be? Yet, the friend reports, Brennan required numerous takes to get his bit-part right, involving little more than a wordless gesture to a fellow salesman. Perhaps that explains why he made a rotten Bible salesman: Brennan was a bad actor. Yet despite his dramatic limitations, in Salesman Brennan remains a flamboyant screen presence with an aching vulnerability. He sings “If I Were A Rich Man” while driving through the sun-kissed streets of Opa-Locka, Fla., in a convertible, chasing leads that bear no fruit. The Maysles had developed sufficient rapport with Brennan that he felt comfortable sharing his private struggles to the camera in the front seat.

The duality that the Maysles recognized in Brennan — to simultaneously perform and to be himself, or share himself— is not a unique quality. It’s present in the character of Iris Apfel, the so-called “rare bird of fashion,” who was Albert’s last documentary subject, and it’s the “very problems of Jagger’s double self” that the explosive Gimme Shelter seeks to illuminate, as the Maysles asserted in their indignant response to Kael’s criticisms.

The Maysles had discovered the documentary potential of the performative “double self” earlier, in a series of short films focusing not on unheralded members of the laboring classes but another group of “rare birds”: Truman Capote, Marlon Brando, movie impresario Joseph Levine (Showman), the Beatles and Orson Welles. These are celebrity portraits, but also something richer and deeper, plumbing the space between public performance and private anxiety to forge a new language — a conceptual foundation upon which the modern vérité form rests.

Although we might loudly proclaim vérité documentary’s independence from the crude vulgarities of Hollywood, the truth is more complicated, at least for those of us who were profoundly influenced by Salesman and other early Maysles films. In the old Hollywood system, as today, too, stars could perform screen roles and then offer carefully packaged, tantalizing glimpses into their offscreen lives to help promote themselves and those performances. Because Hollywood offers a world of make-believe onscreen, there’s no room in the film itself for the second half of the double-self.

What the Maysles pioneered in their early short films was a kind of filmmaking that inverted this relationship, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the star’s inner-life, valuable only because it could be measured against a public image that was already familiar to audiences. “We’re all actors,” says Brando to the reporter next to him, in a series of sustained press-junket interviews that constitutes the revelatory meta-performance of Meet Marlon Brando.

What the Maysles discovered in the feature films is that you could unite performance and self-revelation in the same film if you had the right subjects and the right kind of performance. Of course, Robert Drew had shown the way in the direct cinema films he made with Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker and Albert Maysles by providing a window into political performance and the private deliberations of public figures. It’s nearly impossible to conceive of a Hollywood system in which a star’s personal life is removed from the marketing equation. It seems just as difficult now to conceive of a successful vérité documentary without the double helix of performance and confession. Notable examples include Don’t Look Back, which predates Salesman, and successors such as Marjoe, Harlan County USA, Hoop Dreams and American Movie.

In fiction, stars offered a coherent performance, in which their personal life hovered like an offscreen shadow. Documentary subjects could offer a series of fragmented performances in which personal life was no longer consigned to the shadows, but rather moved to the foreground. This star-making dimension has never squared neatly with the form’s humbler traditions. At Sundance last year — against the advice of my publicist — I invited Pastor Jay Reinke, subject of my film The Overnighters, to share the stage with me at our premiere. I understood her caution but was willing to tolerate the risk that he might say something in the Q&A that would make me cringe, or shatter that very illusion Oppenheimer alluded to. Was Reinke aware of the camera while we were filming? I’m fond of pointing out something that happened later in production, after I’d been filming Reinke and his Overnighters program for about 15 months. If Reinke was in conversation, and I was panning back and forth, he would sometimes wait for the camera to land on him before speaking, or responding. I found this to be highly strange, and yet utterly sensible and rather thoughtful of him.

Like the Hollywood system it inverted, the Maysles documentary tradition spawned a legion of stars, few greater than Big and Little Edie. Marjoe Gortner, the eponymous “star” of the Academy Award-winning documentary Marjoe, came close, building a dubious Hollywood career on his indelible documentary performance. When I recently purchased a DVD of Mark Lester’s redneck drive-in oddity Bobbie Joe and the Outlaw, notable mostly for Lynda Carter’s only nude scene, I wasn’t surprised to discover he had the lead opposite her — a performance sandwiched somewhere between his credits in Kojak and Viva Knievel!

Shortly before he passed away, Albert spoke about the power of documentary to help us “know your neighbor.” It’s an agreeable, sentimental notion. Wouldn’t it be nice if our neighbors included the Beales of Grey Gardens, the Rolling Stones and other titanic artistic figures of the last half-century? After a long career and an extraordinary body of work, Albert returned to his “performance” roots with Iris, an affectionate tribute to the 93-year-old New York fashion maven, known for her vivid, colorful style and signature eye-glasses. Directed when Albert himself was 87, and co-photographed by him, the film is remarkably light on its feet. Apfel is a wise-cracking, resilient and lovable muse, famous for what we’re never exactly sure, other than a style that’s part couture and part thrift – and all resplendent.

A pioneering jeans-wearer, whose career in fabric and design stretches back to the Truman administration, Iris became an “octogenarian starlet” when the Met presented an exhibit drawn from her personal collection of costume jewelry. “I’m not a pretty person,” she says. Yet, she is clearly adored, not just by fashion luminaries like Bruce Weber, but also by Albert himself. The feeling is apparently mutual: affectionate, flirtatious, Iris brings “handsome” Albert into the frame, in scenes that subtly echo Big Edie’s flirtations with David Maysles. A reasonable critic might assert that Iris gives a great “performance” as Iris. But the film is most powerful, ultimately, for its portrait of the relationship between Iris and her husband, Carl. It provides the film with its beating heart. As flamboyant as she is publicly, dispensing fashion bon mots and Borscht Belt comedy, at home with Carl, Iris is devoted and loving. “I’m vertical, so I’m happy,” she tells Bruce Weber, but mortality hovers on the horizon, providing the film with an air of grace that lingers long after the final shot.

Watching Iris in the wake of Albert’s death, we witness a powerful reflexive inquiry, an assertion of artistic vitality that makes the film a fitting epitaph for a filmmaker who continued to tell remarkable stories long past the point that most of us would simply hang up our holster. Ironically, it’s Iris herself who will likely seize the stage at the film’s premiere, without the director who ushered her there. Yet, we have Albert and his remarkable “rapport” to credit.