Back to selection

Back to selection

Rep Reborn, Downtown: The Story Behind NYC’s Metrograph Theater

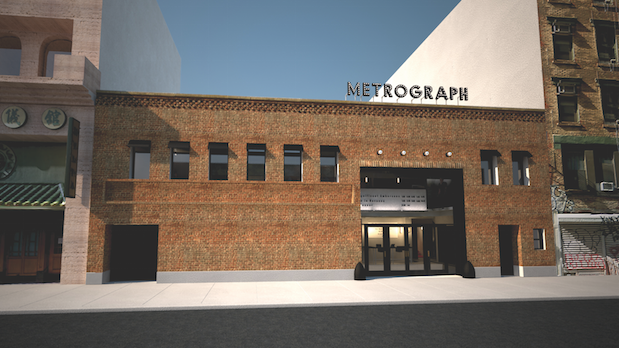

An illustration of what the completed Metrograph will look like (courtesy of Metrograph)

An illustration of what the completed Metrograph will look like (courtesy of Metrograph) Though NYC is one of the best places in America to see repertory cinema, the number of theaters in the city has decreased greatly over the decades. That’s as true for rep houses as it is for first-run venues; the Metrograph will be programming in both fields. When the two-screen venue opens in March, it’ll be the first new independent movie theater to open in Manhattan in a decade; fittingly, it sits across the street from the long-boarded up Loew’s Canal Theatre.

On a mid-December day, founder Alexander Olch, CEO Ethan Oberman and programming and artistic director Jake Perlin walk me through the site. Despite the sacks of mortar and other construction materials strewn around, it’s possible to envision how the space will work. The smaller screen has 50 seats in rows that are 20 feet across, while the bigger theater can accommodate 175: 150 downstairs, 25 in the balcony. This larger screen will be 30 feet across, and chalkmarks are still on the wall from Perlin and Olch marking precisely how big they could make the screen for 1.33 Academy ratio, 1.85 anamorphic and 2.35 widescreen. The front row begins at a reasonable, non-neck-crick-inducing distance from the screen. “We could have jammed in more seats,” Perlin notes. “The idea is that there will be no bad sightlines.” There’s also a candy store on this floor and stairs that lead to a downtown restaurant. This component is called The Commissary, with menus derived from studio cafeteria menus of the ’20s and ’30s (Olch sourced them from eBay, flea markets and other esoteric sources); in a nice touch (assuming the kitchen can keep up), the preparation time for each dish will be listed, helping filmgoers manage their pre-film time. Upstairs, there’s the two-row balcony for the second theater, a cafe/bar area and a bookstore that will sell a variety of film-centric texts. For retrospectives there are plans to self-publish important texts that haven’t been translated into English, as there will also be a space where you can pick up “books that are important, that you should be able to grab any time,” Perlin says. “When we’re open, there will be a copy of [Amos Vogel’s] Film as a Subversive Art on sale.”

Olch and Oberman, who has a background in software companies, met at Harvard, where the former helped produce the latter’s thesis film. Olch (also a fashion designer) went on to make the documentary The Windmill Movie, which Perlin (who’s also worked in distribution) helped release. The idea for the theater came to Olch after finishing Windmill, and he’s spent the last six years trying to realize it. There were false starts at sites on 24th Street and Grand Street before the Metrograph landed at its outskirts-of-Chinatown location. “From a construction/architectural point of view, a movie theater is a very unusual thing to do,” Olch explains. “It requires a wide, open space without columns. If you’re walking into a space that is not a theater, you’re usually talking about knocking down various narrow townhouses or trying to remove columns from a larger warehouse building. It made the project more expensive, more difficult to raise money for and harder to convince landlords that it is going to work. It took a long time to get lucky enough to find this place, which is an unobstructed warehouse that’s 60 by 80 feet and really a dream.”

Experientially, the idea is to provide a comfortable site that functions, too, as a seductive social space. The restaurant will be open for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and Olch envisions the café space serving as a site for meetings and a general base for New York’s filmmaking community. Notably, unlike Manhattan’s other rep houses (such as Anthology Film Archives and Film Forum), The Metrograph will operate as a for-profit business: “We did not even consider” going the nonprofit route, Oberman says. “We feel like we can do this in a for-profit way. People are looking for a little bit different [of an] experience, and that experience can be many things. It can be the experience that you get at an Alamo Drafthouse, it could be the experience that we’re going to give you.”

The level of detail involved in planning the Metrograph extended to Olch designing his own chairs for the auditoriums. “The angle at which your seat is pitched is also a big thing in terms of your comfort and your perception of the screen,” he explains, “because it affects the angle of your face, and therefore your eyes. The degree to which you stagger the seats, meaning the person behind is directly behind your head or they’re between two people, the height differential between you and the row in front of you — all of these things are drawn out in a lot of detail. Your angles with regard to the screen horizontally and vertically are all calculated. It’s probably the only time I’ve gotten to use trigonometry and the Pythagorean theorem since school.” Creature comforts should help attract a steady audience: “I’m counting on people wanting to come multiple times a week,” Perlin says. “I never want someone to say ‘Oh, I’m dying to see that movie,’ but groan at the thought of where they have to go. We want to show a good five-hour movie but not have it be unendurable.” The first round of programming (done by Perlin with head programmer Aliza Ma) includes a full Jean Eustache retro, new 35mm prints of three Frederick Wiseman films, movies about going to the movies including Taxi Driver and Singin’ in the Rain, and a run of Johnnie To’s 3-D musical Office, which only played in 2-D during its U.S. release. There are also plans to program festival films that don’t get distribution, with a 50-50 balance between new films and old.

Perlin, a noted advocate of 35mm programming (his Film Desk imprint reissues films in that format), is pleased that the theater comes with four 35mm projectors, two per theater for ideal projection practices. They’re Kinoton FP 30 Ds, and if they were used cars, Perlin says, “they’d have 50 miles on them.” They’re effectively unused, having been bought by multiple theaters that would then shut down, passing on the projectors to another soon-to-shutter venue or screening room. And so the Metrograph will open as an outlier in two areas: not just a new rep house in the memory of theaters Perlin remembers — the Bleecker Street Cinema (1960-1991), the 8th Street Playhouse (1929-1992) — but a statement in favor of the much-debated ongoing viability of 35mm repertory cinema.