Back to selection

Back to selection

Festival Beat: Doclisboa and CPH:DOX

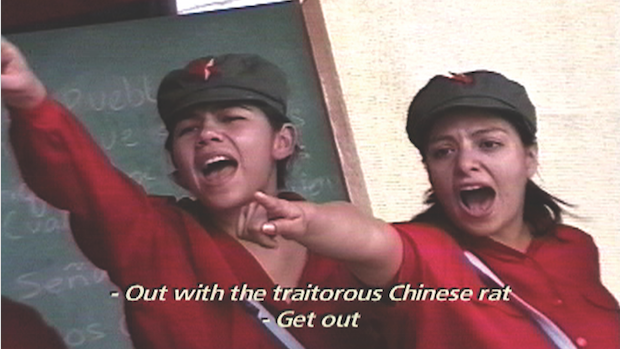

La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo (Photo courtesy of Jim Finn)

La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo (Photo courtesy of Jim Finn) Doclisboa

by Pamela Cohn

“I can’t trust my own memories, and neither should the audience.” — filmmaker Naeem Mohaiemen, The Young Man Was trilogy

A robust and wide-ranging sidebar program at a festival draws on the conventions of the multivolume novel, or the cantos of a long poem, varied portraits refracting off a narrative throughline. Stories both epic and quotidian dovetail and, as a result, iconoclastic interventions and disruptions atomise historical temporality. What’s left behind when the so-called terrorist no longer identifies, or is identified, as such? Or is dead? Or never existed in the first place? Traces of a progression of words are followed by traces of a progression of gestures. The rest is guesswork and mythmaking.

Close to half of the selections were works of fiction in the “I Don’t Throw Bombs, I Make Films” program at this year’s increasingly ambitious Doclisboa International Film Festival, its title taken from RW Fassbinder’s 1979 dark comedy about terrorism, The Third Generation. Most of the works, certainly, use structures and conventions rooted in documentary performance in an attempt at verisimilitude for subject matter that quite adeptly, and by necessity, eludes the truth or elides fact and fiction. Covering a wide swath of time and various histories, the expansive 28-film collection was co-curated by festival director Cíntia Gil along with Agnès Wildenstein, Augusto M. Seabra, Davide Oberto and Tiago Afonso. Eleven of these selections were projected on 16mm, eight of them on 35mm, the warp and weave of unrestored celluloid helping to relay the shock of casual violence, the disorientation and dissociation of individuals who function and operate underground, needing to remain smothered in their anonymity.

For the programmers, the starting point of this retrospective started almost a year ago with what proved to be the very difficult task of securing the rights for exhibiting a 16mm print of Alan Clarke’s 1989 film, Elephant. Clarke’s picture, with its brisk 39-minute running time, influenced director Gus Van Sant so acutely that, 14 years later, he would use the same title and imitate its approach: tracking shots dispassionately recording a massacre with little added explanation or insight. Van Sant had asked filmmaker Harmony Korine to name his favorite movie. Korine responded that it was Clarke’s film, a balletic ode with a Steadicam, the heat-seeking lens as attendant angel of death. What plays out is a dialogue-free killing spree, clocking in at 18 brutal slayings perpetrated before the end credits roll. We are privy to the fact that it’s Belfast — and that’s it.

The proper distance of time needed to portray certain personages and events is essential when reflecting upon terrorism and its representation in cinema. This could be said to be collapsing in a post-9/11 world where the “T-word” has been not only homogenized and misused to frequent deleterious effect within an interconnected and depersonalized network. There are no longer the same imperatives to refine why and how an individual is burdened with the label of “terrorist” as there were 30 or 40 years ago. Are they Red, Black, revolutionary, counter-revolutionary, Left, Right? Are they completely underground, gunning people down in the streets and then going home for supper? Are they working in a closed, independent cell? Are they colluding or unwitting puppets of the state, or in obeisance to an intelligence agency? The heightened artifice of Jim Finn’s brilliant La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo from 2007 — my favorite discovery at this year’s festival — aspires to the conditions of myth, wrangling fractured individuals into a collective symbolism, a mash-up from any revolutionary handbook. A young woman giving a deposition about her complicity in counter-revolutionary activities in Peru states, “When we handled explosives, they advised us to keep our thoughts on our ideology. That would allow us to do everything well … Anything can be made to explode if you apply the right thought.”

In documentary, only the distance of time has enabled many of the most infamous terrorists active several decades ago to appear in front of a camera. During their careers, they certainly were not speaking. They were blowing things up, hijacking, kidnapping and assassinating. In the case of Ulrike Meinhof and Holger Meins — who met in film school — they themselves had to give up filmmaking because they simply could not remain so visible. Bambule, from 1970, a campy film by Meinhof and Eberhard Itzenplitz, takes place in a reformatory for girls, where discipline and bad living conditions lead to a deadly riot. Its TV broadcast was cancelled after an armed Meinhof was involved in the prison break of gang member Andreas Baader.

Japanese directors Koji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi, who made Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War together in 1971, were simultaneously filmmakers and freedom fighters, leaving the discussion of the proper distance of time moot in this instance. As they took themselves to Beirut to document the collaborative struggle of the Japanese Red Army with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, their argument was that making art was just as important as their participatory militancy. It was all part of the same struggle. But at a certain point, they chose not to go further in order to maintain their identity as filmmakers.

In a panel discussion during the festival with four filmmakers with works in the program — Hartmut Bitomsky, Naeem Mohaiemen, Fabrizio Calvi and Mosco Levi Boucault, all of whom have devoted most of their filmmaking to cinematic encounters with terrorists — Mohaiemen noted that Wakamatsu’s and Adachi’s actions, if done today, would probably have them jailed for life. He then mentioned American filmmaker Laura Poitras, who can personally attest to the fact that we live in an age now where filming individuals from the “underground,” or even passing on messages from them, can be considered high treason. But what Poitras (who was not represented in this program), more than anyone in recent memory, has repeatedly illustrated is that power perspectives are quite malleable in a partnership between filmmaker and active revolutionaries or political dissidents.

In certain instances, it’s the filmmakers who are exposed in very explicit ways in order for their protagonists to agree to appear on camera, as in Emile de Antonio, Mary Lampson and Haskell Wexler’s Underground, a film that Poitras also selected for her guest curation at CPH:DOX last year. What this film from 1976 still illustrates so resonantly is that everyone involved is the storyteller, but the lion’s share of the telling power is given to the protagonist who is ready to speak and be seen, a situation Poitras herself has realized through her surveillance trilogy. It is work that has continually upped the stakes on the viability of her own safety and privacy, the level of risk exponentially increasing with each work.

“We were interested in this plurality of ways of representing,” Cíntia Gil said. “We cannot be naïve — of course, there are political issues here. Of course it’s not just about cinema or film language. It was important to ask ourselves, how we can understand this better. Is it by knowing the facts that a terrorist might tell you, or the victims? It’s not just cinema representing terrorism. Terrorism is also a representation of the world — this one we live in now, and that of the future.”

Blurred edges, hinterlands and limbos remain, but in the context of stories on terrorism, what happens in those liminal spaces is what is most worth watching. Terrorism has been, and continues to be, directly influenced by cinema. (See, for example, the Islamic State’s emphasis on professionally filming their various killings.) In fact, cinema has, in many ways, supplied our age with much of its recognizable mythology surrounding the figure of the terrorist.

At Doclisboa, salty realism and an eclectic surrealism were woven through this collection from across the globe. Some works had an overall tonal detachment from the world they wish to annihilate. Some were willing to go down in a blaze of bullets for the world they want to create through their own particular brand of uplift and release from unending oppression.

The cinematic universe of the terrorist can be searing in its purity, and, ultimately, unknowable since what these films acknowledge in their totality is that any understanding of the subject we might have will always be partial and transient. For the victims, however, the vicious beauty of their cinematic universes offer little comfort; their falling bodies still burn, tremble, forget, grieve, misspeak and die in the name of revolution.

CPH:DOX

By Lauren Wissot

I’ve long been championing events and VR as the twin keys to a sustainable documentary film fest future. In a perfect festival world, each individual fest would position itself as its own one-of-a-kind event — or more accurately, a series of unique events adding up to a one-of-a-kind experience. For example, both DOC NYC and CPH:DOX (whose dates frustratingly overlapped this year) screened A Good American, Friedrich Moser’s portrait of NSA whistleblower Bill Binney and his scuttled-by-bosses ThinThread system (that could have prevented the 9/11 attacks). Both fests also smartly featured cyber-hero Binney and the film’s Austrian director in attendance for the Q&A. But only CPH:DOX invited Binney — along with Moser, security journalist Quinn Norton and fellow whistleblower Kirk Wiebe — to participate in a “Cryptoparty: Digital Self-Defense” educational seminar (as part of its technology-focused Reality:Check “democracy lab”). While I certainly don’t mean to single out DOC NYC — as it’s merely representative of the majority of U.S. (i.e., not government funded) festivals — in the 21st century it’s often not enough to simply screen films with a Q&A and expect to pack the house. (And that goes doubly for docs better suited to Netflix, PBS or CNN than to the big screen.) For better or worse, you’ve got to put on an outside-the-box show to stand out from the way-too-crowded crowd.

While CPH:DOX bills itself as the “third biggest documentary film festival in the world,” its proximity to the biggest documentary film festival in the world, both in terms of location (Amsterdam is a mere 90-minute plane ride from Copenhagen) and dates (this year’s edition of CPH:DOX wrapped three days before IDFA 2015 opened), frustratingly makes it feel a bit like a prelude to Holland’s longstanding mega-event. Fortunately, Copenhagen’s feisty Millennial (less than half IDFA’s age) still has the flexibility to swiftly change course and adapt — hence the savvy date change to March that was announced post-fest. Which makes it an exciting player to watch — and perhaps the player to watch when it comes to the hybrid documentary revolution that’s occurring even as I type.

And watch I did. Sixteen films were nominated for this year’s DOX:Award, CPH:DOX’s main international competition, and because I agreed to be part of the Danish film magazine Ekko’s “star barometer” I was tasked with viewing — and rating, on a one-to-four, bad-to-great, scale — every last one. And though Robert Machoian and Rodrigo Ojeda-Beck’s SXSW sweetheart God Bless the Child ultimately (and inexplicably, to my mind) took the top prize, there were four other films from around the world equally deserving of those accolades.

Two of these were years-in-the-making, character-driven studies by female directors whose patience behind the lens paid off in brilliant and unexpected ways. While wholly different in subject matter, Mallory, by Czech director Helena Třeštíková, and Brothers, by Norway’s Aslaug Holm, shot over seven and eight years respectively, are both composed of a series of quiet revelations that ultimately add up to pure transcendence. Initially skeptical of Brothers, with its “documentary answer to Boyhood” tagline, I found myself immediately sucked in from the very first frame. Holm, an acclaimed DP, filmed the simple daily lives of her sons Markus and Lukas from the time they were five and eight years old. Her artistic attention to detail, combined with lush cinematography and an elegiac score, brings to mind not Linklater, though, but Malick. And in that same spirit, Brothers is no sentimental home movie, no nostalgia trip, but a strikingly gorgeous attempt to capture the moment-to-moment, elusive beauty of childhood.

In contrast, Třeštíková’s Mallory is a restrained, cinema vérité portrait of a heroic ex-junkie with a heart of gold defying the odds (until life throws her yet another cruel punch). The titular subject is a struggling single mom with a young son who lives with her boyfriend in a car – and has institutionalized that son to keep him safe. Victimized by an insane bureaucracy (everyone in the Czech welfare and housing departments seems to be on vacation at all times, and when they do become available dole out brochures titled “Homeless in Prague” in lieu of actual aid), Mallory appears caught up in the very same system that her fellow countryman Kafka wrote about a century ago. And with Třeštíková’s suspense-inducing editing, we’re never quite sure what the next cut will bring for Mallory’s (mis)fortunes. In one scene another homeless person has broken into her car to sleep; a few months later she’s overjoyed after landing a new job. When she finally finds a place to live, looking around the flat she notes, “Look, a plant! I’ve never had a plant.” Mallory’s heartbreaking, up-and-down existence — the very precariousness of homelessness — hits home, so to speak.

The other two films that blew my mind were most memorable for stretching the limits of the documentary form. As has been noted, CPH:DOX has long been celebrated (and sometimes vilified) for its cutting-edge embrace of hybridization, and I can think of no other film so suited to the fest than Italian director Pietro Marcello’s Locarno-premiering Lost and Beautiful. A jaw-dropping, Pasolini-influenced melding of Campanian myth with the true story of Tommaso Cestrone, a.k.a. the “Angel of Carditello,” the caretaker of an abandoned palace who succumbed to a heart attack during Marcello’s filming, Lost and Beautiful is an intoxicating work of timeless magical realism. It’s also a fine example of the exhilarating possibilities within today’s realm of cinematic nonfiction.

Finally, I had the good luck to discover Huang Ya-li’s The Moulin, a riveting 160-minutes of avant-garde filmmaking, in which the style of this Taiwanese director thrillingly mirrors his surrealist subject. The doc’s title refers to “Le Moulin,” a group of Western-leaning poets in 1930s Taiwan that banded together in artistic protest against Japan’s cultural hegemony. From faceless bodies cast in shadow, to grainy historical footage, to the artists’ calligraphy-rendered letters, to images of Picassos, Huang bombards us with eye-catching visuals that also serve as a tribute to the classic (Western) experimental filmmakers, from Buñuel to Deren. Indeed, every cut of this tour de force leads to a delightful cinephile surprise. A sentiment that also pretty much sums up my experience at this final November edition of CPH:DOX.