Back to selection

Back to selection

Digital Motion Picture Cameras in 2016: New Horizons

Sony 4K PXW-FS5. In 2016, small is beautiful.

Sony 4K PXW-FS5. In 2016, small is beautiful. In this, my sixth annual camera round-up for Filmmaker, I’ll explore the latest developments and trends associated with cameras — as I have each year — which taken together continue to define new directions in digital cinema. I’ll highlight cameras that exemplify these trends. Those seeking an end-in-sight to a decade’s worth of profound change in camera technology might want to stop reading here.

In my 2015 camera round-up, I touched on issues of design including modularity, new materials, a return to ergonomics; the birth of camera apps; wirelessness and the dawn of camera IP connectivity; the mirrorless revolution with its new lens mount designs; sensor windowing and phase-detection autofocus; and a renaissance in small sensors. (Revisit last year’s round-up for a quick brush-up on these topics, if need be.)

I also sketched the now-critical role of the Internet, which transmits the latest product announcements — camera introductions, for instance, live-streamed from show floors of NAB and IBC — and marketing initiatives to legions of young, smart enthusiasts who, in turn, download camera manuals, upload test footage, swap comments, and eagerly update firmware and software. World events no longer hold a monopoly on 24/7 coverage.

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine mastering the ongoing intricacies of today’s cameras, codecs, gammas, LUTs, sensor formats, what have you, without an assist from Google, YouTube, Wikipedia, or online communities like Cinematography.net (home of “CML,” Geoff Boyle’s influential Cinematography Mailing List), DVXuser, or REDUSER, all of which long ago turned the palm-sized ASC American Cinematographer Manual, that well-worn staple of every working DP’s kit 30 years ago, into an object of nostalgia. (Recent editions notwithstanding.)

It would be no exaggeration to say that the very culture of contemporary digital cinematography — worldwide — is predicated on the speed and scope of knowledge provided by, exchanged over, the Internet. Free.

In other words, don’t be a stranger to its riches. If cameras are your thing, subscribe to or visit terrific camera blogs like photojournalist Dan Chung’s Beijing-based Newsshooter or user-driven No Film School. Or watch on Vimeo or YouTube Dave Dugdale’s gentle, discursive camera demos; or Three Blind Men and an Elephant Production’s Hugh Brownstone’s wry, discursive commentaries; or literally dozens of others like them. If you’re hooked on social media, follow them on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

So, what new horizons await digital motion picture cameras?

In two frighteningly short years, 4K has gone from the imposingly high end to the impossible-to-avoid in new cameras, even those aimed at consumers. Forget about last year’s breakout Sundance film Tangerine being shot in HD on an iPhone: not only did last year’s iPhone 6s and 6s Plus introduce 4K capture, they enabled 4K editing on iMovie too.

Quick math shows that the 12-megapixel camera in the iPhone 6s provides more than enough pixels for 4K. (3840 x 2160 = 8.3 megapixels.) But how does the slender iPhone 6s slipped into your back pocket process, record, and output a huge 4K signal? The iPhone’s trick is that it employs an advanced, high-compression H.264 codec to squeeze subsampled color (4:2:0) into a low bit rate (about 50 Mbps, barely twice that of standard-definition MiniDV).

The point being, not all 4K is born equal. While it’s always the case that 4K presents the viewer with four times as many pixels as HD, pixel count per se does not equal 4K resolution — it merely offers the potential for 4K resolution. How sharp is that pea-sized lens in the iPhone 6s, anyway? Or the fixed zoom on that $2K consumer camcorder? Are they any match to a Zeiss Master Prime, which will set you back $20K? Perhaps it would be more useful to think of 4K as akin to Apple’s Retina Display technology: Look Ma, no pixels!

Finer pixels, of course, can serve as a marketing hook to sell the latest cameras and flat-screen TVs, or to hype online programming — here’s looking at you, Netflix and Amazon. But where cameras are concerned, the arrival of 4K technology brings immediate benefits to budget-conscious filmmakers.

As HD becomes the new SD, costs of HD drop. HD-only camcorders that lack 4K, but which are otherwise superb, are discounted. Meanwhile, as solid-state media like SD cards climb in speed and gain capacity to accommodate the faster bit rates of 4K, earlier versions of the same media, more than fast enough for HD, also get discounted.

In the realm of codecs, more pixels and faster bit rates drive compression advances needed to squeeze massive 4K signals into even thinner bit streams for distribution by Blu-ray, cable, over-the-top (OTT), Internet streaming, and tomorrow’s over-the-air broadcasting (OTA) — while widespread manufacture and adoption lowers costs. High-level versions of H.264 like Sony’s XAVC make their way into codecs of evermore affordable cameras to reproduce images with unprecedented quality relative to their small file sizes. Meanwhile, H.265, a newer standard and twice as efficient, is ready to go. You could say that a rising tide of more efficient compression floats all boats.

Yet another side benefit of 4K is the turbocharging in 4K cameras of signal processing and internal data pathways. Virtually all 4K cameras can also output HD, and when their blazing-fast internal processing is applied to HD, this can make possible 1080p frame rates of 120 fps and increasingly 240 fps at full quality, even in inexpensive camcorders. Slo-mo we could only dream of a few years ago! (You won’t be surprised to learn the iPhone 6s, too, can do 1080p at 120fps.)

On the optics side, the greater resolving power of 4K has spurred lens manufacturers to up their game, including their more affordable lens series. Canon’s superb Cinema primes and zooms were conceived with 4K in mind. So, too, Sony’s latest G Master (“GM”) E-mount lenses, which, although full-frame, were designed with an eye towards the resolution needs of the smaller Super35 4K frame. For its GM lenses, for instance, Sony claims a target resolution of 50 lines/mm, markedly higher than the 10-30 lines/mm typical of full-frame lenses in the past.

And in the offing is 8K, believe it or not, breathing down the neck of 4K. 8K packs 16 times the pixel count of HD, about 33 megapixels. (Still photographers won’t be put off by this number, which the latest DSLRs and mirrorless cameras exceed.) For several years now at NAB, Japan’s NHK has demonstrated prototype 8K cameras along with broadcasting and display technology. (I’ve attended each of their 8K showcases. Truly impressive.) Look up “Ultra-high-definition television” at Wikipedia and you’ll see that two UHD standards exist equally, 4K and 8K, and that H.265 will reproduce 8K at 50mbps (same bitrate used by the iPhone 6s to capture 4K). 8K is no longer of question of if, but when.

Given this push towards greater pixel density, the current fad in some digital cinematography circles for vintage and uncoated lenses with softer detail, pronounced aberrations, flares and veiling glare — “character” — can be viewed as ironic. Our equivalent to vinyl. That’s fine with me. Soft textures and faded palettes belong in our graphic vocabulary.

But where optimizing sharpness is concerned, counting megapixels is only the beginning. Our perception of sharpness in motion images is defined by not one but three realms of resolution: spatial, temporal, and tonal. New cameras are advancing rapidly on each of these fronts — so much so that when seriously discussing new cameras, a basic understanding of these realms is no longer optional.

What most people understand as camera resolution — pixel count– — is potential spatial resolution: horizontal pixels multiplied by vertical pixels.

Pixel count suffices as resolution in still cameras, but motion pictures occupy an additional dimension: time. Frame rate represents how thin each sample of time is sliced. The thinner the slices, the greater the temporal resolution. Watching a fast-paced soccer tournament at 120 fps is a different experience from watching it at a conventional 24 or 30 fps. At today’s 30 fps, a traveling ball is a blur. (Easily verified in a freeze frame.) At 120 fps, as the ball shoots through the air, you can make out every detail in its seams. (Perhaps why Ang Lee is currently shooting his military drama Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk at 120 fps. Also 3D.)

Tonal scale is the third type of resolution. Think of tonal scale as a gray scale, a fixed number of discrete steps of brightness, from blackest black to whitest white. Digital color images, in fact, are made of three overlaid tonal scales, one each for red, green, and blue. (Combined they form a gray scale.)

Like spatial and temporal resolution, tonal resolution increases as its samples (steps) are made smaller in size. Capturing digital color images with 8 bits per color provides 256 steps from black to white (256 steps each for red, green, and blue). 10-bit recording provides 1024 steps. 12-bit, 4096 steps. 16-bit, 65536 steps (or 256 times 8-bit).

Why does tonal “bit depth” matter? Because the human eye can distinguish 10 million colors. The finer the steps of red, green, and blue, the finer the degrees of color that can be reproduced by mixing them. For me, the experience of increased color depth is something “felt” by the eye, if otherwise difficult to describe or quantify.

A bit depth of 8 has been standard since digital video arrived in the 1980s. Even today, most consumer and low-end pro camcorders are 8-bit; ditto the LCD displays we watch them on. A chief reason 8 bits has remained popular is that when digital video recording jumps to 10 bits or 12 bits, the size of the resulting bit stream or digital file leaps exponentially too. One consequence, however, of cameras acquiring faster signal processing and advanced compression is that 10-bit and 12-bit recording are rapidly gaining ground, notably in under-$10K “affordable” professional camcorders.

Advanced compression is also poised to allow base frame rates of 60p and 120p for streaming and broadcasting (in addition to today’s 30p and 1080i). UHDTV and ATSC 3.0 broadcasting standards, both works-in-progress, already anticipate these high frame rates, as does the NHK’s 8K. Such high frame rates are known by their shorthand, “HFR.” You can think of the increased slo-mo capabilities appearing in the latest camcorders as a warm-up for HFR.

In addition to base frame rate, UHDTV and ATSC 3.0 will expand tonal resolution along two dimensions: color gamut and dynamic range. These shifts are something several of today’s latest cameras already anticipate.

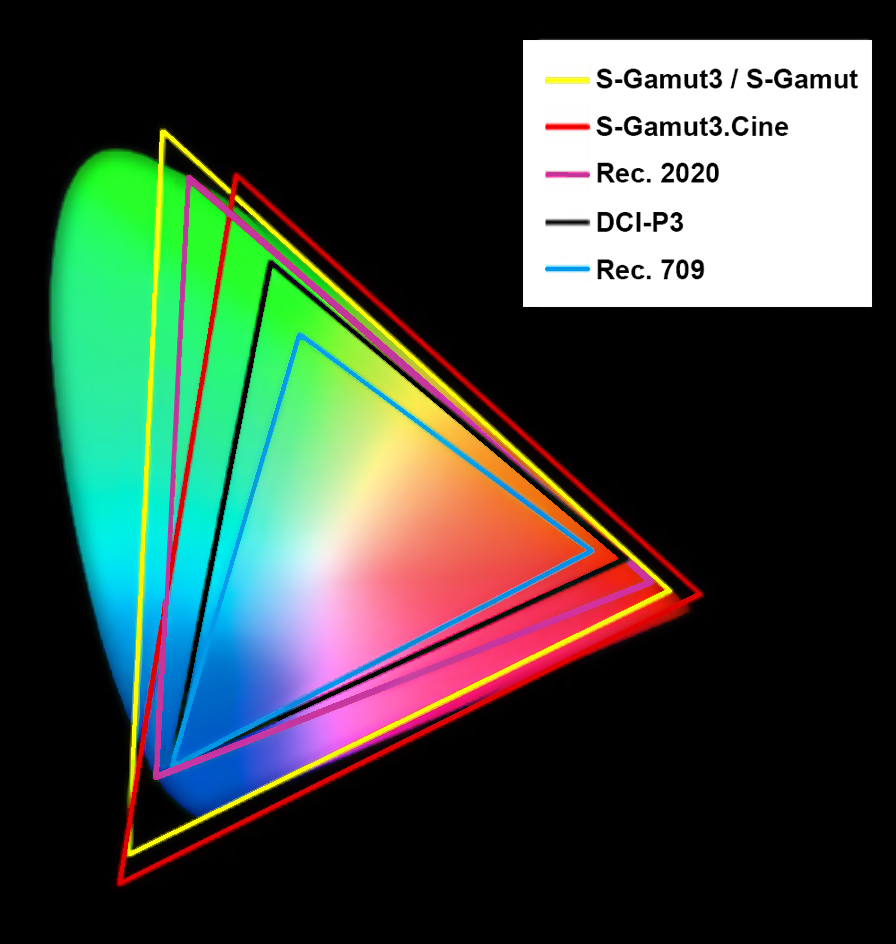

The familiar Rec. 709 digital video color standard, introduced in 1990 for HD, reproduces only 36% of the colors seen by the human eye. (sRGB in computer displays reproduces exactly the same gamut, with a slight difference in gamma.) The new Rec. 2020 standard for 4K and beyond, introduced in 2012, reproduces 76% of the human visible spectrum, nearly twice as many colors. Put another way, a camera encoding to Rec. 2020 can reproduce colors a Rec. 709 camera cannot.

At present, dynamic range is constrained by the display devices we view– — cinema screens and LCDs — the brightness limits of which were limited by the technology of their day. In the case of cinema screens, a century of lamp-house and lens technologies set limits of brightness, as did flammability and melting point of the film frames in the projector gate.

In the case of LCD TVs, the contrast and brightness range of NTSC images were defined in the early 1950s, when a standard image transfer function (gamma) tailored to cathode-ray tubes was locked into place. HD, originally under development as analog in the 1980s, essentially perpetuated these analog-era standards.

But what if our display devices, in terms of dynamic range, were to catch up to the digital 21st century?

Enter high dynamic range. “HDR” can be a confusing term, because presently it denotes two different techniques. In Adobe Photoshop, for instance, using “Merge to HDR,” you can automatically combine identically framed photos, one overexposed to capture deep shadow detail and the other underexposed to capture clouds in a sky, into a composite photo that depicts an extreme tonal range no single photograph could otherwise capture. The HDR function on the iPhone uses three exposures to accomplish the same thing.

A related technique in motion pictures is HDRx, unique to the RED EPIC and Scarlet. HDRx captures a secondary darker exposure (faster shutter speed) in the interval between primary exposures, for later combining.

In each of these examples of multi-exposure HDR, a broad tonal scale existing in nature and visible to the eye has been simulated — merged or otherwise compressed together — for display on a screen that cannot otherwise display them all at once. But what if a new type of screen technology could depict deep shadows and realistically bright skies at once, as the eye actually sees them?

This would, of course, require a display that could simultaneously reproduce true blacks (like an OLED already can) as well much brighter highlight detail — think of being outside on a sunny day. A display, in other words, that would significantly extend the gray scale at the highlight end and incorporate a larger Rec. 2020 color gamut with the necessary 10-bit or 12-bit resolution per color.

And it is this type of HDR that was standardized in January by an industry-wide consortium of film studios, electronics manufacturers, and content distributors calling themselves the UHD Alliance. Their UHD (4K) will sport a new logo, ULTRA HD PREMIUM, when rolled out to consumers, offering them a striking new dynamic range — deeper blacks, 3-5 times increase in brightness (depending upon factors including how bright you drive your current TV) — and an unprecedented Rec. 2020 gamut of deeper and truer colors.

(Will a red Coca-Cola can finally look true-to-life? Rec. 709 can’t do this, but Rec. 2020 will. However there exists no display capable of full Rec. 2020 — it’s “aspirational.” Laser projection comes closest at the moment. ULTRA HD PREMIUM specifies a Rec. 2020 signal input but settles for displaying 90% of DCI-P3, itself a smaller gamut covering 46% of the visible spectrum, created for theatrical film projection. 90% of P3 equals 41% — only marginally better than Rec. 709’s 36%. Something to do with getting ULTRA HD PREMIUM-branded TVs into the market as fast as possible?)

Will all of this affect cameras? You bet it will. High-end cameras like ARRI’s Alexa, RED’s Weapon series, Panasonic’s VariCam 35, and Sony’s F65 and F55 that claim a 14+ stop dynamic range will be able to forgo kludges like current log gammas devised to stuff a modern camera’s wide dynamic range into a 1950’s-based image, and instead show off the longer tonal scale they faithfully capture in the first place. Sony cameras, incorporating a gamut considerably larger than Rec. 2020 since at least 2002 (not a typo, almost 15 years ago), when S-Gamut2 was introduced into the F900, will be able to really strut their stuff.

My comments below about select current cameras are necessarily brief, scattershot, and anything but comprehensive. As mentioned in last year’s camera survey, a renaissance in small-sensor cameras is underway, featuring 4K cameras with sensors in the neighborhood of 1/3-inch. Factoring the burgeoning world of mirrorless still/video hybrids along with an ever-broader product range of large-sensor cameras from all manufacturers, at all price points, it’s practically impossible any longer to cover, no less summarize, the entire field.

But know this: what only a few years ago was high-end has been mainstreamed. Genuine choice now abounds. Every camera out there has its quirks, and a resourceful DIY attitude — with a little help from the Internet — goes a long way towards ironing them out. If there is a take-away from my quick dip above into the deep changes roiling the technology of motion images, it’s that those of us privileged to use and understand these cameras are in a unique position to participate in defining the cinema of the 21st century. What an exciting trail to blaze!

Sony

Sony remains the acknowledged world leader in CMOS sensors, with untold millions of smart phones like Apple’s iPhone exploiting their small sensor magic. Advanced still cameras by Hasselblad, Nikon, Samsung, and Olympus also rely on Sony’s leading sensor technology, for which Sony has pioneered backside illumination, CMOS stacking, large pixels, and fast read-out — all of which improve signal-to-noise and enable today’s stratospheric ISOs and crazy-fast frame rates. In January Danish company Phase One introduced their XF 100MP medium format camera with a 101-megapixel sensor co-developed with Sony, delivering 16-bit color and 15 stops latitude. Such achievements have created a kind of online craze for tracking Sony sensor breakthroughs. Already there are rumors that the Sony’s next mirrorless cameras will contain 70- to 80-megapixel sensors.

Nonetheless, at NAB this year Sony’s conference motto will once again be “Beyond Definition.” As mentioned above, Sony long ago pioneered wide-gamut encoding in cameras and is equally anxious to advance emerging HDR standards. Their HDR demo at last year’s NAB featured footage of a brightly blazing lakeside campfire at dusk, then at dawn. As reproduced on an X-tended Dynamic Range Bravia TV, it was so lifelike, my skin felt a phantom sensation of heat — but with a conventional digital photo displayed on a conventional screen, I can’t fully reproduce what it looked like!

HFR also factors prominently into Sony’s camera agenda. At 2015 NAB Sony took the wraps off their first 2/3-in. 4K field camera, the HDC-4300. At NAB this year Sony will introduce a companion Ultra High Frame Rate (UHFR) 4K camera system, the HDC-4800. With a PL-mount and global shutter (naturally), this beast captures 4K up to 480 fps and HD to 720 fps. It supports both Rec. 709 and Rec. 2020. There’s no way the HDC-4800 is not going to be all the rage at sports channels.

Where bread & butter cameras are concerned, Sony has just had a banner year. Their 8K-enabled F65 and popular F55 and F5 platforms, 4K and 2K industry workhorses respectively, have been steadily updated with new features. (Despite the F65’s name, its sensor is Super35.) For instance, a just-announced 16-bit AXS-R7 Raw Recorder with a Version 8 firmware update will double the F55’s maximum 4K frame rate from 60 to 120 fps and add a brawny 480Mbps XAVC codec.

Meanwhile, the affordable, ergonomic PXW-FS7 has sold like hotcakes, exceeded sales expectations. Then in September, what looks like a miniaturized FS7 — the PXW-FS5 — was introduced into the mix. It’s already become another hit. (More on the FS5 below.)

Equally impressive have been the market penetration of Sony’s E-mount and the parallel success of Sony’s groundbreaking E-mount Alpha mirrorless cameras. I hesitate to call them still cameras, because although they take the shape of a still camera, they were conceived as video/still hybrids. The a7S and its successor, the a7S II, for instance, were designed around 4K sensors.

Sony’s E-mount is the first lens mount designed from the outset for both stills and video use. As a result, mirrorless and video cameras across Sony’s various product lines, whether APS-C (E) or full-frame (FE), share the same E-mount. Over the past year I’ve shot multiple docs and a feature with an FS7 and a7S combo, or FS5 and a7S — but have had to manage just one collection of lenses, shared by both types of camera. Mighty convenient!

Perhaps this is why the past year has seen a tilt in the lens industry towards E-mount products. Zeiss has introduced no less than three E-mount lines, called Touit, Loxia, and Batis (after exotic birds). Samyang/Rokinon, Veydra, Sigma, Tamron, Voigtlander, and Venus Optics have also lept onto the E-mount bandwagon.

I read a recent comment, if I recall correctly, by Sony CEO Kazuo Hirai confirming the inevitable merging of still and video technology. So-called “convergence” was Jim Jannard’s central conceit in founding RED — creation of a Digital Stills & Motion Camera or “DSMC” — and remains a flashpoint for those opposed to crossbreeding stills and motion cameras. Polemics aside, convergence as a practical matter is already well under way, with stills and video cameras sharing more than lens mounts.

For example, I understand that the PXW-FS5 employs a fast Bionz processor(s) of the type mainly associated with mirrorless Alpha cameras. That might help explain why the FS5’s personality is somewhat different from its larger sibling, the PXW-FS7. (Hold on to this thought, we’ll come back to it.)

Like the FS7, the FS5 is a sub-$10K 4K Super35 camera with special attention given to hand-held ergonomics. At first glance, indeed, it appears to be a miniature FS7. A closer look reveals an adjustable, removable smart handgrip attached to the side instead of to an arm, like the FS7. Rather than nestling on the shoulder like the FS7, the FS5 is designed to be held in front of the body like a Handycam. What makes this bearable is the FS5’s compact size and its light magnesium frame — body weight under 2 lbs. — along with the balance/control imparted by a super-comfortable handgrip (close to the camera’s side). Even with lens and battery, the FS5 hardly tops 5 lbs.

With the exception of the rear viewfinder — a real one, one of my favorite features —every accessory can be stripped off: LCD, handle, smart handgrip. Ideal for drone use. In my hands, the stripped FS5 feels like a 16mm Bolex. If I wanted to go stealth with this minimal configuration, minus the handgrip, I would add a tiny directional capsule mic by attaching a thin XLR cable to the camera body’s single XLR input. This audio-recording strategy is possible because the FS5’s audio controls are on the body, not on the removable handle. Also, only one XLR input is set into the handle, not both XLRs. Small, thoughtful details like these set the FS5 apart.

Another thoughtful detail is the flexible mounting of the LCD, easily attached at the front of the handle or at either side of the handle’s rear.

FS5 features shared with the FS7 include an E-mount, a grip that’s smart (menu control by thumb joystick), SD cards as media, S-Log3 with SGamut3.Cine, and 10-bit XAVC (Long-GOP only for FS5).

But several of the FS5’s key features are unique to it. Clear Image Zoom takes advantage of surplus pixels in the FS5’s 11.6 megapixel sensor — 4K requires only 8.3 megapixels — to enable what I call dynamic windowing. When a camera like the FS5 is oversampling — capturing more pixels than its recording format can reproduce — Clear Image Zoom permits the camera to dynamically shrink or expand its window of active pixels, resulting in an apparent zoom in or out.

A good way to visualize this is to consider the case of using the 4K FS5 to shoot HD in particular — a case where, for me, Clear Image Zoom becomes the equivalent of an FS5 killer app. By dynamically windowing — during a shot — from the larger 4K area of active pixels down to the central 1920 x 1080 minimum needed for HD, the FS5 achieves a 2x zoom effect. This virtual zoom effect is on top of any optical zoom range already offered by a servo-zoom on the FS5, and it’s controlled by the FS5’s rocker switch — with feathering — just as a real servo-driven zoom lens would be. In fact, if a Sony servo-zoom is mounted on the camera, the rocker switch will first drive the optical zoom to the end of its range, then the 2x Clear Image Zoom will kick in. The FS5 will see the two zoom ranges as continuous.

It’s important to grasp that Clear Image Zoom is not digital magnification, like the cheesy image enlargements associated with reality-TV and entertainment-industry shows. (Which can lay claim to their own aesthetic, I suppose.) With Clear Image Zoom, pixels don’t grow larger as you zoom in. They remain the same size.

Indeed, Clear Image Zoom acts like an ENG zoom lens doubler, only without the stop loss and optical degradation. I repeat, there simply is no light loss. No optical aberrations are introduced. With Clear Image Zoom, zoom lenses obtain twice their original range. The remarkably super-wide, optically stabilized Sony 10-18mm zoom pictured on the FS5 at the top of this article becomes, effectively, 10-36mm. A longer 70-200mm zoom becomes 70-400. Each prime — even fast f/1.2 lenses demanded by marginal lighting — becomes a 2x zoom, or twice as telephoto. You can see how this would extend your entire lens kit in terribly useful ways.

The FS5 also provides Center Scan for mounting 16mm lenses. (Center Scan just arrived for the FS7 at the end of January, with the Firmware Version 3 update.)

Lastly, the FS5 introduces a Variable ND system that is unique to large-sensor cameras, and creatively useful. It has two modes, Preset and Variable. Preset offers the usual Clear, ¼, 1/16, 1/64 ND settings, but Variable permits the operator to continuously dial in any amount of ND from ¼ to 1/128. Let’s say you’re shooting outdoors and the sun is continuously going in and out of the clouds. You can smoothly adjust the variable ND level by hand, as you see fit. This avoids big jumps in ND, or shifts in depth-of-field caused by iris adjustments. With Firmware Version 2 update for the FS5 — promised later this year — an Auto Variable ND filter function will be introduced. This should operate akin to auto-iris, only, I repeat, without altering depth-of-field.

Firmware Version 2 update will also add RAW output for externally recording the FS5.

I mentioned the FS5’s personality. There have been quirks. Initially the FS5 couldn’t, at the same time, record 4K internally and also output a 4K image for monitoring/recording via HDMI. A firmware update fixed this, but traded away the LCD image. If you output 4K HDMI and use the LCD, you lose internal 4K recording.

The base ISO for S-Log3 is a lofty 3200. Many have struggled with noisy images as a result. Some apply the ETTR fix (expose to the right one stop). When shooting S-Log3 with the FS5, I have found DaVinci Resolve’s superb noise reduction to be my best friend.

The reason I have detailed the FS5’s size, weight, design, and wondrous new functions like Clear Image Zoom and Variable ND is that I think this is that rare camera that introduces a number of new forward-thinking elements all at once, which someday will be taken for granted as standard features in most cameras.

Today, however, they’re still new, fun and exciting to explore.

Last year, as mentioned, I found myself often taking two E-mount cameras to set or location: whatever I was using as an A-camera plus my little Sony a7S. I’ll discuss Alpha mirrorless cameras in a moment— but first want to mention that I have also, for some time, been experimenting with a different combination of cameras, a Super35 camera plus a small-sensor camera. Cameras are small and affordable enough these days to make this practical.

Nothing beats a Super35 camera for handsomely lit interviews and landscapes. But following around an agile documentary subject with a large-sensor camera is never less than challenging. I have my tricks-of-the-trade, but I’m always sweating the focus when hand-holding a Super35 camera.

In those situations, why not just let a small-sensor camera with its deep focus — whether HD or 4K — do what it does best?

Last summer off Nantucket, for a documentary about a notable furniture designer, I shot sailboat races from a powered boat. The subjects were bobbing at a distance, and so was I. Luckily I brought along a Sony XDCAM PXW-X180, a 3-chip 1/3-in. Handycam-style camcorder with a 25x optical zoom, that happens to incorporate the same Variable ND as the FS5. (First camcorder to offer this feature.) The 25x G Lens was so telephoto, and the optical image stabilization so effective, that I got perfectly smooth footage at a distance, hand-held. Recorded as 10-bit, XAVC Intra — no sacrifice there. With what other camera could I have achieved this happy result as easily? — I realized afterwards. Shooting the races was an impromptu move. But I had camera choices that day.

Sony, like Panasonic and Canon, makes a range of HD, now 4K, small-sensor, hand-held professional camcorders that are worth keeping track of. In Sony’s case, there are at least six current XDCAM handheld camcorders, including two 4K models, the PXW-Z150 pictured above and the bantam PXW-X70 (via optional 4K upgrade).

What the Z150 and X70 have in common is a Sony Exmor 1-in. CMOS sensor with 14.2 effective megapixels. A 1-in. sensor is a smidgen larger than Super16 film, so it’s helpful to think of it as the digital equivalent of Super16.

Funny how our two basic professional sensor formats — Super35/APS-C and 1-inch — have come to parallel the two traditional film formats, 35mm and 16mm.

Mirrorless Alpha E-mount cameras and E-mount camcorders arrived on the scene at the same time and sometimes feel like an extension of each other. However, while E-mount camcorders can’t take stills, E-mount mirrorless cameras can take great video, with a few precautions and provisos.

The original a7R and a7S have in the last year been upgraded to a “II” version newly capable of internal 4K recording (3840 x 2160p at 30, 24 fps, Long-GOP XAVC-S, 8-bit 4:2:0, 100 Mbps). Each camera has acquired “5-Axis SteadyShot INSIDE Image Stabilization,” which by stabilizing the sensor corrects for five types of image shake — possibly a godsend when hand-holding longer lenses.

While the a7R II is limited to S-Log2, it gains much-needed phase-detection autofocus. With its 42 megapixel sensor, it can record 4K in either full-frame or Super35. The big-pixel, 4K low-light champ — a7S II — gains S-Log3 but no phase-detection AF.

Both are prey to rolling shutter. But given their low cost and extreme portability, both have generated extraordinary video around the world, as a trip to YouTube or Vimeo will demonstrate.

Canon

Canon is a color science company. You could say color is their main product, and the cameras they make are just tools to get some.

If some camera people take issue with the ergonomics or compact shape of the Cinema EOS cameras, particularly when it comes to hand-holding, no one complains about the color or quality of the resulting images.

Nor build quality. Canon seems to take pains not to cut corners. Nothing on a Canon camcorder feels flimsy.

Canon has yet to break through in the mirrorless market, although their EF-M mirrorless mount and Sony’s E-mount share an identical 18mm flange focal depth. Meanwhile, their L-series EF lenses remain the standard by which other “affordable” lenses are compared. High-end Canon Cinema Primes and Zooms also come in EF mount. Digital motion picture cameras incorporating EF mounts include models from Blackmagic Design, RED, and Panasonic.

On the design front, Canon remains distinctive. The little 4K XC10 shown above, hardly larger than its lens, all but says “drone me.” It also takes stills.

The only question is, in the run-up to NAB 2016: will Canon introduce a camera beyond 4K, perhaps in a different form factor?

Panasonic

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Sony’s FS7 must have a big head by now. Squint at the profile of the VariCam LT with the EF-mount rig above, and you’d think it’s an FS7. The winner in all of this paring down is you and me, since lightweight and hand-held make VariCam LT friendlier to use. As owner of L-series EF-mount lenses, VariCam LT already makes me want to toss it on my shoulder and go.

VariCam LT uses the same Super35 sensor as its heftier sibling, VariCam 35, and retains VariCam 35’s unique dual native ISO of 800/5000. As in the case of VariCam 35, V-Log can deliver 14+ stops, harnessing Panasonic’s wide V-Gamut. (Nearly identical to Sony S-Gamut3.)

Note the two cables to the right of the name VARICAM: power and SDI, both for the viewfinder. In principle, any viewfinder with an SDI input can be used. Blackmagic Design’s URSA Mini also features an SDI-driven viewfinder, which means the two cameras should be able to swap viewfinders. In any case, perhaps this incipient trend will spur a market in third-party viewfinders, causing features to grow and prices to drop.

Like Sony, Panasonic makes two lines of pro handheld camcorders, AVCCAM and microP2. So far Panasonic’s only 4K handheld camcorders — which seem to exist on their own — are the AG-DVX200, introduced at NAB last year, above, and the HC-X1000. The HD-X1000 uses a single ½-in. 18.47 megapixel sensor, only 8.29 megapixels of which are active when capturing 4K — no way this particular camera isn’t going to be noisy.

Panasonic’s menu graphics are crisp, clear, and colorful; in other words, design attention has been paid. In the DVX200, I particularly appreciate the large and sharp waveform display in the LCD —truly useful and one of best I’ve encountered in a camera viewfinder.

Last fall, Panasonic’s Lumix DMC-GH4 —the little mirrorless Micro Four Thirds camera that could — got a welcome firmware update, Version 2.4, to V-Log L gamma used by VariCam 35, although some users complained about the $100 cost and convoluted activation process.

ARRI

Minutes into my first viewing of The Revenant at a pre-release screening in Manhattan, I knew something was different in the look of this film. Somehow I guessed immediately that it had to be an ARRI Alexa 65. How else to capture the scope of sublime detail in those expansive but merciless landscapes?

Despite anything you’ve heard about major film companies rejecting use of Alexa, telling DPs they can’t use Alexa because its

4K is slightly up-res’d, not the real deal — no worries. When ARRI wants to introduce an Alexa with greater pixel density, it will. It has.

RED

Full availability of RED Digital Cinema’s new arsenal, er, family, of DSMC2 (Digital Still and Motion Camera 2) products is due by mid-year.

MG denotes magnesium body, CF, carbon fiber. I spent considerable time at NAB last year handling a carbon fiber 6K Weapon with Dragon sensor, going over its feel, fit, and finish. I walked away impressed. Like a carbon-fiber bicycle, the 6K Weapon Carbon is a lightweight work of art and engineering at once. Delightful to touch and to operate. Rubber handles are satisfyingly solid and grippy, the viewing screen is perfection, bright, sharp, detailed. Ditto the menus. A well-executed design, all-around.

Among other improvements, DSMC2 brings support for direct recording of ProRes and a little later, Avid DNxHD.

Some DPs take issue with RED’s strategy of increasing resolution by increasing sensor size. Which, in turn, requires lenses of greater coverage, often a new set. Which further requires a DP long-experienced in shooting Super35 to re-learn angles-of-view for his/her new, wider-coverage lenses. Which most DPs would prefer not to have to do.

Sony, by contrast, adheres to fixed sensor sizes and increases resolution by increasingly pixel density.

The many ways to skin a cat…

Blackmagic Design

URSA Mini

Since dipping into the camera business, Blackmagic Design has produced a menagerie of unusual forms and designs, often at strikingly low prices. I say more power to them, even if some of these products are awkward or impractical. That’s how natural selection works: survival of the fittest. Meanwhile, new ideas are tried and refined. If you never think outside the box, you stay boxed in.

BMD introduced their URSA Mini 4K at last year’s NAB as a hand-held compact camera with a global shutter and a modest price. There’s a lot to like. Although it’s heavy — 14.2 lbs. with a large brick battery, as pictured above — it’s solid and well-balanced, like a CP-16 film camera from yesteryear. The front of the shoulder rig has 15mm rod holes; underneath is a Sony VCT-14 fast-release tripod adapter interface. Nice.

There are no built-in NDs, nor auto focus, nor auto iris. Forget stabilization.

The URSA Mini 4K is really an old-fashioned film camera. The image will be as steady as you are. The viewfinder is very sharp, you can focus without aids. (As mentioned above, separate SDI and power cables from the viewfinder attach to the camera body.)

Another thing BMD gets right: CFast cards and ProRes HQ. I shot directly to ProRes HQ. I mixed HD and 4K files on the same card. Everything played back on my MacBook Pro, directly from the card, if needed. Fastest, simplest workflow ever.

It’s no state secret that with a choice of three slow ISOs — 200, 400, 800 —URSA Mini 4K is no low-light marvel.

In March of this year, a high-end 4.6K version of URSA Mini began shipping (along with a 4.6K version of the Micro Cinema Camera) — minus a promised global shutter which Blackmagic said it couldn’t perfect in time. As it happens, the URSA Mini 4.6K’s 15-stop wide dynamic range is not available anyway when using the global shutter; only when using the rolling shutter. When beta-testers expressed a preference for dynamic range over the missing global shutter feature, BMD decided to release the camera with changed specs.

Send in the Drones

This brief overview of 2016 digital motion picture cameras is titled, “New Horizons.”

The best way to see over a new horizon is to gain some altitude.

I won’t dwell deeply on the topic of cameras for drones, except to convey a quick impression. The GoPro Hero4 Black is not a drone camera, but many are familiar with the quality of its 4K/30p video, if only on the Internet. No one will mistake a GoPro’s output for that of an ARRI Alexa, but, like the talking dog, the wonder is not what the dogs says, but that it can talk at all. Like a 4K iPhone video, under the right circumstances 4K GoPro footage can be damned impressive. (It’s often moving too fast to dwell on video issues, anyway.)

So it should be no surprise that drone outfits like DJI are building their own 4K cameras, the better to integrate them into their small flying machines. Dinky though they may be, these cameras can be excellent for what they are —and they’re getting much better.

The new DJI Phantom 4 features a 1/2.3-in. 12-megapixel sensor with ISO to 3200. The built-in wide-angle lens is f/2.8. It can shoot 4096 x 2160 at 24/25 fps, or 3840 x 2160 up to 30 fps, recorded to H.264.

I predict every camera manufacturer will be, if they aren’t already, marketing a sophisticated, diminutive camera tailored to the needs of drone or hand-held gimbal work, and promising quality significantly better than a GoPo or Action Cam.

In February, Sony announced availability of a new kind of sensor, a 1/2.6-in. stacked CMOS sensor with 22.5 effective megapixels, featuring built-in hybrid auto-focus — contrast-based and image-plane phase detection — plus 3-axis electronic image stabilization, which can correct camera shake and lens distortion.

No moving parts. Lower power consumption. Ideal for flight.

Now stir in a pinch of Clear Image Zoom, and voilà!