Back to selection

Back to selection

Why I Will Not Put My Film Online: A Filmmaker’s Response to Covid-19

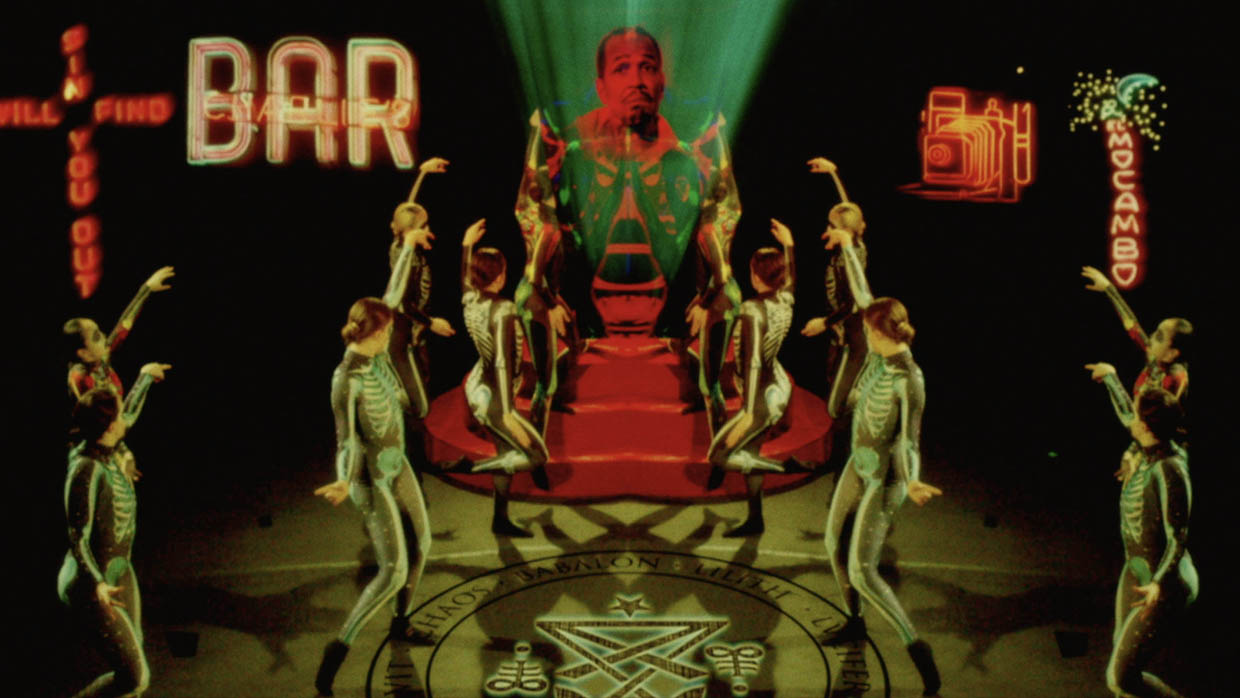

Sammy-Gate

Sammy-Gate Back in the days when I used to distribute avant-garde cinema on home video, I asked my friend George Kuchar about releasing Hold Me While I’m Naked and a few other of his classic films on DVD.

“I can’t let you do that, Noel!” he explained. “You see, my films are legendary because nobody can see them. If someone could just go out and rent one, they’d find out they stink. I’ve got to maintain the legend!”

George was sort of joking. But there was a kernel of truth in his statement.

Kuchar might have been wrong that his films stunk. His influence upon John Waters, Todd Haynes, and contemporary art is beyond dispute. But there was no question his films weren’t easy to see. Of the several hundred videos that comprise his filmography, I saw a good share of them only because I visited his San Francisco apartment in the mid-2000’s.

My friend Dan Carbone and I had a Saturday night ritual. We would meet George at the Red Jade restaurant on Church Street. After dinner, we’d climb the stairs to his third-floor walk-up in the Mission for coffee and ice cream. George would screen one of his films on an old television in his bedroom. Then his twin brother (and roommate) Mike would take us down the hall and show one of his films on the TV in his bedroom. We called their bedrooms “Cinema #1” and “Cinema #2.” The apartment served as a multiplex of a sort.

Aside from a few major titles, most of their videos were not publicly available. Some probably had not been viewed by more than a handful of people in decades. George had to dig out the original mini-DV or Hi8 cassettes and play them for you.

What made these evenings at Cinema Kuchar so memorable for me was not just the works themselves. It was the act of uncovering and seeing something unknown and precious. And being able to enjoy the work in the presence of its creator further rarefied the experience. Perhaps, that was what George meant by “maintaining the legend.”

As we all know, there has been a trend — or, better put, a frenzied stampede — towards making films more convenient to see on televisions, laptops, and mobile devices over the last 10 years. This development has been a mixed blessing for independent filmmakers. It is much easier to self-produce and self-distribute your film. But the ubiquity of the moving image has also cheapened it.

For those who remember the 1970s — a time before even the VHS player existed, the cinema possessed a greater power than today. To see a film, you had to enter a theatre, a ritualized, immersive space that projected spectacle onto a 30-foot screen. When you left the movie palace, there was a feeling in your gut that you had returned to the “real world,” a place a little less magical, a little more banal. Yes, we had television but the medium was a pale imitation of cinema in an era before 72” HD flatscreen televisions and home theatre systems.

Today, however, the eye is bombarded with the moving image. Animated displays appear on billboards and buildings just as Blade Runner presaged. If you pump gas at an Arco, a digital monitor built into the fuel island blares ads from “Gas TV.” According to eMarketer, the average American spent three hours 10 minutes per day looking at their smartphone screen in 2019, much of which likely involves the digestion of video content.

In the age of corona, the only place you can’t see a movie is a movie theatre.

For an indie or arthouse director, this is a really shitty time to release a new film. Theatrical exhibition is out of the question. Promoting your work feels unseemly in a time of death and despair. And the main outlet for screening an undistributed film are “virtual” online festivals.

Please don’t get me wrong. I program for a film festival (Slamdance). Many of my best friends are film programmers. I know we festival creatures want to put on a brave face and prove “the show must go on.” But you will never replicate the Grand Palais with Zoom. And watching filmmakers premiere their work on the small screen in the midst of a pandemic is a very bleak proposition for one and all.

Not only does the online format devalue film. It devalues the festival through the implication that a website can substitute for the excitement and pageantry of the live event. Wouldn’t it be more dignified to just sit out a year?

I was lucky (sort of) to have a live premiere in 2020. My film Sammy-Gate opened to packed theatres at IFFR in January. Four months ago, those crowds represented enthusiasm and buzz. Today, I guess we would regard them more like petri dishes of contagion.

Like any filmmaker, I anticipated the unveiling of my debut feature with a combination of excitement and trepidation. In my case, however, the premiere had assumed an almost mythological degree of significance due to the project’s long gestation.

With an awesome team of seasoned studio folk, many of whom worked pro bono, we slowly and lovingly shot the film scene-by-scene from early 2013 to late 2018. Some of it was captured on 35mm Panavision gear and glass from the 1970s. Some of it was shot on RED Monstro and Digital Bolex. And the rest of it was animated frame by frame.

The project took eight years to complete. I don’t mean we wrote a script and then waited seven years for financing. I mean dozens of people worked on the feature for years and years and years. This film was the product of creative energy and sheer willpower.

So after a long, hard road, this labor of love now appears destined for the digital oblivion of the Internet during a pandemic. And even in the best case scenario, my film will become a disposable media object to be consumed by a preoccupied public between bouts of binge-viewing and doom-scrolling.

Please note I am not writing this article to whine or wax nostalgic. I am writing with a message of hope and a plan of action.

Today, there are a plethora of “think pieces” on how filmmakers can adjust to “the new normal.” The common denominator involves the Internet. This technology makes films easily available to a captive audience under lockdown. Never mind that your low-budget independent work will compete in an overcrowded media marketplace with billions of other videos.

But what choice do you have?

The answer is simple. Do not put your film online.

If streaming video is fast food, it is time for us to consider slow food.

So here is my mini-manifesto. If it must have a name, let’s call it Dogma-19.

When health experts rule that public screenings may resume safely, I will only show my film to live audiences. I will attend the screenings. I will answer questions, tell stories, and hang out in the lobby until the usher kicks me out. Maybe the 2021 festivals won’t screen it because your film turns into a pumpkin 12 months after its premiere. Maybe only a dozen people will come to see it. Theaters won’t be able to host full houses with social distancing anyway. That’s OK. I’d rather impact a small number of people in a profound way than a large number of people in a forgettable way.

My confessedly Luddite outlook is not unknown to other fields. For instance, the resurgence of vinyl indicates a movement away from musical convenience. And who doesn’t love a deluxe gatefold? Jack White’s magazine “Maggot Brain” is only available in print form through mail-order. And my friend Matvei Yankelevich just sent me a big, heavy box, filled with books of Russian conceptualist poetry from his Ugly Duckling Presse.

Holding one of those chapbooks in my hands feels different than swiping through Arial text on a Kindle.

We have made it easier and easier to see our films online. Perhaps, we should try to make it a little bit harder.

No filmmaker can stem the flood of content that flows through the pipes of the Interwebs each day. But we can decline to participate in this digital meat market.

Yes, I know this mission is quixotic in nature. But I do not think I am alone in this sentiment. So if any other filmmaker wishes to charge this windmill alongside me, speak out! Maybe you can upload a YouTube or Instagram video in support of this cause. How else will we be able to spread the word?

#Dogma19

Noel Lawrence makes, curates, distributes, and writes about film. His debut feature Sammy-Gate just premiered at IFFR 2020.

As ringleader of Thee J.X. Williams Archive, Lawrence produced a body of audiovisual work that critiqued institutions and historical discourses of cinema. His work has screened in the Louvre and squats worldwide. More recently, Lawrence has collaborated on projects with Bootsy Collins and Iggy Pop as well as co-curating the Department of Anarchy section for the Slamdance Film Festival. Noel may be working with Darius James on an adaptation of Ishmael Reed’s Cab Calloway Stands In For The Moon or D Hexorcism of Noxon D. Awful. IG: @psychedelichistory