Back to selection

Back to selection

“This is Going to Be the Most Circuitous Interview”: Alan Rudolph on Breakfast of Champions

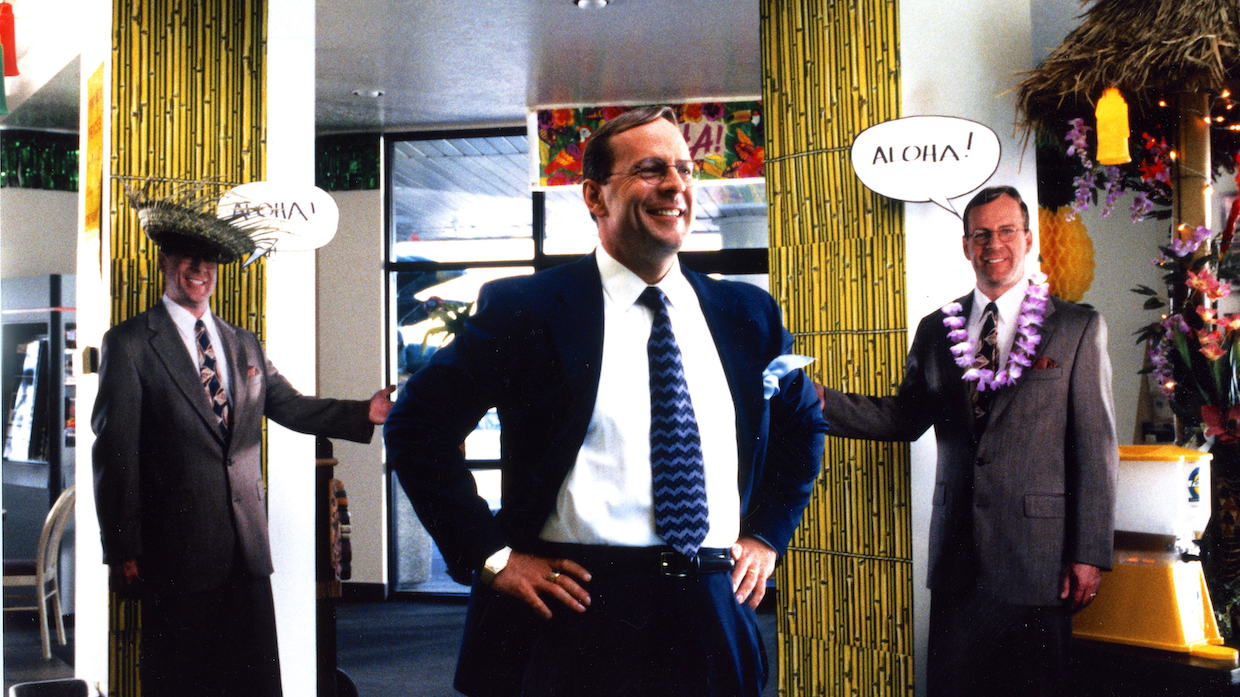

Bruce Willis in Breakfast of Champions (photo by Joyce Rudolph)

Bruce Willis in Breakfast of Champions (photo by Joyce Rudolph) 25 years ago, Alan Rudolph’s Breakfast of Champions left theaters as quickly as it arrived, barely making a blip during a landmark year in American cinema save for a litany of negative reviews that all but celebrated its failure. (Luc Moullet might have been its sole admirer upon release.) Adapted from the Kurt Vonnegut novel of the same name, Breakfast captures a cross-section of American archetypes on the brink of a collective nervous breakdown; correspondingly, the film also feels like it’s also losing its mind. Rudolph, cinematographer Elliot Davis and editor Suzy Elmiger imbue Breakfast with a manic, comically grotesque tone that mirrors the director’s feelings about advertising, politicians and a country that prefers to keep up appearances rather than address the rot at its core.

Poised to be reevaluated by a public more inured to the bizzarro cacophony of the media landscape and celebrity hucksterism, a new 4K restoration returns Breakfast to theaters just in time for the aftermath of a turbulent, consequential presidential election. Not only is the film a curious entry in the career of a regrettably underrated American filmmaker, it also might be the most damning, sui generis view of American excess distributed by a Walt Disney subsidiary. Nothing else in 1999 (or 2024) remotely looks or sounds like it.

Over a lengthy, digressive conversation mirroring the spontaneous nature of his work, I spoke to Rudolph about the film’s origins, his consequential relationship with Robert Altman, his experience working with Bruce Willis (and his then-wife Demi Moore), his Hollywood childhood and much more.

Filmmaker: How many interviews have you done about this movie on this jaunt?

Rudolph: It’s act three for me. Act one was when I wrote it for Altman. Act two, when we actually made the film, I didn’t do any press. They didn’t want any. Maybe I did, but I don’t recall any. It’s the strangest experience. I love the film. When Bob [Altman] was thinking of making it and I wrote it, I just thought, “I can’t wait to see what he does with it.”

Filmmaker: The novel came out in ’73.

Rudolph: I wrote it on the set of Nashville, because he knew I was trying to get a film of my own made, but there was nowhere to go for any of it then. It was pretty hard to want to do something outside of him because every day was a revelation. I had a lot to do. I worked as hard on Nashville as I have in my whole life.

Filmmaker: You were the AD, correct?

Rudolph: The lines blurred. It’s a long story. But [Altman] saw me talking with Richard Baskin, the musical director, [came] over at lunchtime and says, “I know you want to make a film. I’ll get that film made in three years. First, I need you to write some things.” He walks away, eats a sandwich, comes back and says, “I don’t care what you make. Just don’t make it a car chase movie.” That was the only thing he told me. Welcome to L.A. came out of that.

We got back to L.A. and he said, “I got writers on [Breakfast] and nobody can crack it. I need it quickly. Have you read the book?” I said, “No”—it probably was a year or two old. I read it in a day, and it basically changed my life, because it confirmed everything. It was hilarious. I went in to see Bob and he said, “What do you think?” I said, “Oh man, it’s fantastic but…” He said, “How quickly can you write it?” I said, “Well, I don’t know. When do you need it?” “Now. I can’t do anything unless I have a script. It’s terrible. Nobody knows how to do it.”

Filmmaker: It’s a fairly faithful adaptation.

Rudolph: I got brutalized for breathing when it first came out. I read one review and never read another. It pissed me off. I got more defiant, but there was no one to get defiant to. I never ever met one single human being from the studio ever, which was great.

A late friend of mine, Jon Bradshaw, he and I wrote The Moderns. We had it for about 10 years and were turned down by everyone. People in the street turned us down. Bradshaw was a [contributing] editor of Esquire and said, “I got a great idea. I think there’s an angle here: ‘The most rejected script in Hollywood.’” I said, “I don’t want to be the answer to a trivia question. I want to get this movie made.” We never did when he was alive.

Filmmaker: That’s one of your better reviewed films, ironically.

Rudolph: Choose Me was the only one that people kind of okayed. I was always going to be in Altman’s shadow, which I took as a compliment.

Filmmaker: I figured they would hang you with that.

Rudolph: Oh, even now—probably your first sentence is, you know, “Protege…,” which, to me, was an honor. I came through the ranks of the crew, even though I knew from a very early age I didn’t want that. First assistant director is a career. I mean, it’s probably the most important guy on the set outside of the director. I was the youngest one in Hollywood. This is going to be the most circuitous interview…

Filmmaker: This is the stuff Filmmaker likes.

Rudolph: I wrote Buffalo Bill for him; I’d written Breakfast for him and another script based on a really terrific book, Easy and Hard Ways Out, written by an engineer who worked in a defense plant on Long Island, Robert Grossbach. The script didn’t get made. The book got adapted [into Best Defense (1984)] and was entirely different. The book was about the madness of the military industrial complex. It was all about this one lowly engineer; his job was to get the epoxy that puts together this microscopic piece that becomes the center of the missile defense system on a jet aircraft. I wrote a script, then something else would come for real and [Altman would] go do that. It was after I wrote Breakfast, so there was a lot of Breakfast in it. I made it madder and more insane.

Anyway, so back to Breakfast. All [Altman] told me was “Don’t follow the book.” I went back to New York to meet Vonnegut. He read the script, was supportive of it and said the exact same thing to me 25 years later when we made the movie: “A book and a film are independent of each other. Let it inspire you, but you have no obligation to make the movie the book, and don’t worry about what I’ll think because the more different it is, the happier I’ll be.” When the film came out, everybody said “This is an impossible book to adapt…and the guy didn’t follow the book!” Which independently can be true, but not together.

Filmmaker: I think you did actually follow the book pretty well. In the book, Vonnegut is a character. You don’t do that. But other than that, the characterizations are the same, it ends and begins the same. It’s much more faithful than I was anticipating.

Rudolph: I’m remembering casting ideas. I wanted Johnny Carson [as Duane Hoover], and he was with us for a second but then backed out. Alice Cooper was going to play Bunny. Bruce [Willis]… Dear Bruce. I haven’t had any contact with him for a long time. You get close to actors when you make movies, even if you don’t know them, even if you just met them and never meet them again. If you’re in charge of their behavior for a specific purpose, you become like war buddies. And Bruce, he’s an artist. He made his career choices and, I assume, got exactly what he wanted, which was money and fame and success, but he had great taste. He was always reading a book a day! He had great taste in art. He knew history as well as anybody. I say in the past tense not because of his condition, but because I haven’t seen him in 20 years. But Bruce was supportive, loyal, friendly. He was like a master of ceremonies in many ways, and a serious, serious actor, but not in a disruptive way, at least in my experience, which started with Mortal Thoughts.

I was hired at the last minute because there was a movie in trouble, and nobody would touch it. My kind of movie! My pattern was basically to try and do my little movies for free, then when nobody had any money and the mortgage was due: “Oh shit, how do I…” I wasn’t offered a lot of things, so it was movies that couldn’t get a director or a director dropped out. I just tried to make them work and get some of the people I’d been working with paid, so then we could get another year or two without being unemployed. Mortal Thoughts was a $6 million movie, and they didn’t know how to do a $6 million movie. Like a couple of studio films I’ve been involved in, you couldn’t mention that they were behind it, because they didn’t want anybody to know they were doing this kind of movie. It was Columbia. I never met anybody from there. I met one of the eight producers because he used to work at Technicolor Lab and was a good guy, but nobody came around.

Demi [Moore] was the producer. An agent I had at the time sent me something when I was in New York and said, “You have to read this right now if you’re interested in it. It’s a murder/thriller kind of thing with Bruce Willis, Demi Moore and Harvey Keitel.” I said, “Are you kidding? You’re sending it to me?” He said, “Yeah, but it’s not a big studio picture. It’s a low-budget thing. Read it and we’ll talk.” I was going to Toronto that night; I read it on the plane and in the hotel room. [Executive producer] Taylor Hackford called me at two in the morning and said, “Did you finish it?” I said, “Yeah, but it hasn’t got an end. It just stops.” He said, “We’re working on the ending. Will you do it?” I said, “When do I start shooting?” “Monday.” “Which Monday?” “Next Monday.” It was, like, Thursday. They must have bent some rules. I said, “Fantastic!”

He said, “We fired the people who were working on it.” I said, “I don’t want to see any of that. I don’t want to know any of that.” There’s a technicality, though—I’ve encountered it twice—that you’re supposed to watch footage with the insurance guy, the bond guy and the producer to say officially, “I don’t want to use any of this footage.” I said, “I won’t do that,” and he said, “You have to do it or the picture goes.” I don’t know who the first director was or why they replaced him. I think he might have been inexperienced. But they had recast a role, so they were obviously not even going to use any of it. I think it was all done before Bruce shot any footage. I’m not trying to disparage whoever that first director was, and I never met him. I don’t even know his name.

Filmmaker: I think it’s probably better that way.

Rudolph: But I said, “I won’t look at old footage. That’s like going through someone’s underwear drawer. I don’t want to see the actors and the light that you don’t want to use. Just let me run with it.” They fired the cameraman, who was a big-time cameraman—or he walked, one of the two—so I got Elliot Davis, who ultimately shot Breakfast of Champions and shot my previous film, Love at Large. He was about to go do a documentary. I said, “Elliot. Monday. New York.” So, he came. I wanted to meet the actors, and met Demi and she was fantastic. She was the co-producer, I think they gave her that credit to get the movie made. I treated her as the producer. I’m not sure everybody was happy with that on the production side. But I said to her, “You’re on the set every day. You’re the producer. We’re going to have a lot of decisions to make. I’m only turning to you if you can handle it, because you’re also the star and I want to get you the best performance you can get.”

Filmmaker: And she was married to Bruce at the time, right?

Rudolph: Yeah, they were hot. We’re shooting this little movie and I could see the two of them had never taken this drug before, which was the only drug I knew from Altman-land: The film is all that matters. There are no rules in terms of what you have to do other than scheduling and all that. If you come up with ideas, run with them and let’s work them in. The script was the last best idea. Elliot and I would get to the first day of shooting in a house and say, “Well, you can’t shoot here. It’s mahogany and brown.” I would turn to the AD and say, “Who’s here?” “We’ve got these two.” “You know that scene that we were going to do later on? Let’s do that outside for about half a day while they repaint the whole house.” And people got into it! You could see the frustration of some really good talent, the production designer and whatnot, but it worked out so well. Though they never came up with that written ending. It kept getting squeezed and squeezed and squeezed. After shooting it, I didn’t want to shoot the Polanski ending, which is the one I think everybody wanted, where the person you’ve been investing your time with, you hate her after all this, because I spent a lot of time trying to like her! I got nailed for the ending, but it wasn’t 100% on me because they didn’t have anything.

Filmmaker: Did the three of you come up with it?

Rudolph: No, Bruce was gone by this point. He didn’t meddle with it. He got to do it the way he wanted and it was great.

Filmmaker: He was fantastic in that movie.

Rudolph: He was very public about that. He said, “This is my finest performance.” When we started Breakfast, we talked a bit and I kept saying, “I see this guy as every politician who skirts the truth, who can’t face the truth and then when he has to, nobody’s home and there’s nothing to draw from, and he wonders, ‘Who am I?’” He said, “I know how to play this guy: Paul Muni.” And he wasn’t talking about the big broad performances, not that Paul Muni was known for that. I think he was talking about the hurt and the struggle. As Bruce was growing up, Paul Muni might have been his guy; he kind of looked like Paul Muni. Bruce never cheated on our films, ever. He never said, “Let’s get this over with.” And he was going through a lot of shit at the time. I found that they were splitting up and it hurt me so much, because they were wonderful.

First thing the crew do when you get a movie and they haven’t met you—which didn’t happen to me a lot, because I grew crews and moved people up—but on Mortal Thoughts, say, or Songwriter, they put these director chairs right out with your name on it. I’ve never sat in them. I’d say, “Don’t ever bring it. Give it to the actors. I’ll never sit in that chair ever.” And I never have, but it’s so funny how they treat the director. My way of doing films is kind of egalitarian, and I got the whole [showing the] dailies [to the actors] thing from Bob.

Filmmaker: I was going to ask about learning things from Altman, and I feel like the egalitarian spirit is definitely one of the things you took.

Rudolph: Yeah! Well, first of all, my dad was in the movie business. His career was up and down in Hollywood. He was a child actor in silent film. His mother was Eugene V. Debs’ campaign manager. Took the family out from Cleveland in probably the nineteen-teens and decided to go to Los Angeles. He was an actor, then in rough times he was an extra. He became Cecil B. DeMille’s assistant director when there were no guilds, but the day it gelled was he was an extra in some movie—you know, The Saracens or something like that, hundreds of extras on a sound stage during Prohibition. My dad, who was a wonderful guy, said you’d put your flask in the arrow quiver of the guy in front of you. You’d take the flask out while you’re waiting to shoot, and you’re standing there for hours, so everybody’s drunk all the time. There are all these phony rocks on a sound stage, and the stunt guy is supposed to jump from this rock to that rock and couldn’t do it. DeMille’s up there with his megaphone: “Is there anybody out there?” “I’ll do it,” my dad says. He gets up there and does it, and DeMille used him on a few films, then made him his assistant director. My dad was one of the… not “founders,” but there at the beginning of the Directors Guild as an assistant director, and he was the top assistant director at Paramount. He did Billy Wilder’s first film. They always gave him movies with new directors. Then television came in, and he became a director. I mean, I’m old. I remember when television came in as a thing. It was actually what made me want to leave Los Angeles, because on the black-and-white TV, a little Dumont television, the World Series is on. It’s always East Coast then, and the people were cold and it was 102 in Los Angeles. I said, “I gotta get out of here.” I never wanted to live there even as a kid, because there was no weather. I’m a rain hound. When I got my driver’s license, I’d drive up to the Pacific Northwest. I knew that better than L.A.

You want a story?

Filmmaker: Sure!

Rudolph: So, we lived in the San Fernando Valley. I was born in Hollywood on a street that no longer exists. You could buy a cheap house. A lot of people moved there. Wasteland. A row of houses had just been built, and we had one, and the neighborhood grew up around us. Then television came in, and kids would all come to our house because we had a TV set. On Saturday afternoons, they’d get one of these probably child molester drunks to come on as “Engineer Joe for the kiddies out there!” The kind of guy that ten years later was arrested. Anyway, he would show Laurel and Hardy, which still to this day are the greatest thing. We’d watch this guy’s train go around with milk in it, then he’d show ten minutes of Laurel and Hardy. Later I learned that half of those segments were [the 1938 feature] Block-Heads cut up. So, kids would come to my house, we’d watch Laurel and Hardy, then go out and play football. I was probably seven years old and threw a football that bounced into a house with the front door open. My friends said, “You threw it. You go in there.” I go in there and a British maid comes out exactly the way you’d picture a British maid: “Was that your football?” “Yeah.” “Better go in there and get it.” I go into a library—the house was as small as ours was, but books everywhere. This elderly man—anybody over 35 was going to be elderly to a seven-year-old kid, but he looked like he was at least 50—with a cardigan sweater said, “I believe you’re after this.” It was Stan Laurel! For a kid, this is an acid trip: You see something on this box, then the guy is next door and he’s not young anymore. I saw him a couple times. He’d sit on his porch and he would wave.

Filmmaker: I’m curious, especially on Breakfast: what kind of direction do you give actors?

Rudolph: None of it is, “Well, do this.” I think it is for some people. I’m self-taught about everything. I worked for two or three days as a second AD on Elia Kazan’s The Arrangement. I was on the Warner Bros. lot shooting something else and somebody got sick or had an accident or something and they said, “You take over because they want the top people over there, and you’re good.” The first scene on this film when I came aboard was Kirk Douglas and Faye Dunaway sitting on a couch—forty takes before lunch and twenty after. I was young and just starting, and I thought, “I’ll never make it. I don’t understand the difference between take 16 and take 58.” A few years later, I’m working with Bob, Elliott Gould and Sterling Hayden [on The Long Goodbye] and it was like firecrackers compared to the Mars station. Altman just had it from the beginning of his life. At his memorial, Garrison Keillor said “Altman was piloting bombers at age 19. You think a studio is going to scare him?” If you’ve ever been in a B-17, it’s just cold and metal, and that’s it. Nothing, nothing scared Altman.

I thought I was going to get into the director’s field when I finally decided I wanted to be in the movie business. Nepotism was a bad word, so I had to go through the entire training program. They don’t want your name; they give you a number and you take an SAT test, and only if you’re in the top ten will they talk to you. Luckily, I got in there. I became a second assistant very quickly in a bad period of Hollywood when nothing was going on, so I got out quickly, then became a first in a minimum amount of time. I was doing television and got a call from somebody I’d worked with saying, “20th Century Fox wants you to be the first assistant on one of their biggest films.” It’s in Europe. The Great White Hope. Martin Ritt is the director; James Earl Jones playing Jack Johnson. I come in and meet the heads of the production. They said, “We want you. Cut your hair.” I said, “No.” I had lost a brother in the war, it changed my whole life. It got me in the movie business because I didn’t want that truck to hit me and say, “Wait, I wish I had…” My brother was older than me; he was 21. He bought me a camera and a motorcycle, and I would go around shooting little films for guys in film school. Anyway, they say, “Cut your hair.” I said, “No, I won’t do that.” The production manager pulls me aside and says, “Are you out of your fucking mind? Do you know the guys they could have asked to do this? I recommended you.” I said, “I can’t. I won’t do it.” “You’re making the biggest mistake of your entire life.” “Probably, but that’s the way it is.” He said, “Why is hair so important?” I said, “I don’t know, but it is.” It was a statement of some kind during this time, Nixon and everything else.

I started writing for myself. I turned everything down. It was a year. I was broke. I get a call from somebody I worked with, and they say, “Are you still an assistant director?” I said, “Not in practice.” “Oh, you’ve got to come and meet these people. You’re going to love them.” I hadn’t seen M.A.S.H., I don’t know why. I thought Altman was a young Canadian director because he did That Cold Day in the Park in Vancouver. But I said, “I don’t want a job.” “Oh, come on. You’ve got to meet these people. I’m going to have the first assistant call you.” “I haven’t been a second assistant for three, four years. I’m not going to be a second assistant!” They said, “It’s different here.” So, Tommy Thompson, Bob’s producer and first assistant, calls me up: “Listen, we’ve heard about you. You’re the right guy.” I said, “I don’t want to be an assistant director.” He said, “The lines blur. Don’t worry about it. Whatever you’re used to, this isn’t it.” On the phone, I decided, I was going to say “yes,” because my mother’s maiden name is Altman—no relation. I told Altman that 20 years later in the backseat of a cab in New York smoking a joint. He looked at me and said, “Well, I’ll be a suck-egg mule.” I still don’t know what that means, but he was from Kansas City and it sounds very Kansas City to me.

Anyway, I said, “OK, I’ll come in and meet him, but I’m not going to cut my hair.” There was a laugh. He said, “Oh, I don’t think that’ll be a problem.” So, I go to meet him. It wasn’t a studio; it was a little building, a complex. No signs, no names. You walk in the courtyard. There’s a guy sitting at a desk: “Oh, are you Alan? Come on in!” We talked, and he was funny. I assumed this was Altman. He eventually said, “Okay, now let’s meet Bob.” It was Tommy Thompson. Then we stepped down into Altman’s office, which had mobiles and brass of helicopters from M.A.S.H., and here’s this large man, sitting at his desk, playing solitaire with tarot cards. I don’t know if that’s something he invented. Tommy says, “Bob, I’d like to meet Alan Rudolph.” He never looked up and said, “Cut your hair!” He had X-ray blue eyes that would look right through you. He could hear people at the window talking. Sometimes you’d be right in the middle of telling him something and he’d just leave, go over and tell a guy to fuck himself. He said, “You’re not going to accept this now?” I said, “I just don’t know.” He said, “My movie opens today. Go see it at the Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Come back Monday and we’ll talk.” It was McCabe and Mrs. Miller. I saw it six times that weekend. Got there early on Monday and said, “Anything you want, I’ll do.”

I don’t know what he saw in me, but he really liked me. He was approachable and unapproachable the whole time. He wasn’t like a regular human. He really was the smartest guy, the quickest guy, and he looked at life at a whole different angle. He’d come up with everything brand new and original, just the opposite of what you thought was true. We went out to dinner once during Long Goodbye. I finally got enough nerve. I said, “Do you always change the script like you’re doing now?” He said, “What? I didn’t change anything.” Now, this was a script written by Leigh Brackett, one of the writers of The Big Sleep. I don’t think there was a line of dialogue from the script that’s in the movie. He said, “I don’t ever change the script,” and he was serious. Still, to this day, I’m twisting around it, and I realized that it’s not the dialogue, it’s not even the structure, it’s the spirit of things and it’s the inspiration. It’s jazz, you know? You take what was given and do your thing with it. The key to that was everything was open. So you could go to Bob, approach him on his major motion picture with Hollywood stars, and say, “What if this happened?”

Filmmaker: I think that’s why actors loved him so much.

Rudolph: Well, actors loved him because everyone was equal. That’s why he made them all come to dailies—not so they could see their work, but so they’d root for the other guy. And Bob would focus on other people as opposed to the star. It was part of his whole global view of art.

Filmmaker: I see so much of him in your work, obviously, but your sensibility is much different than this.

Rudolph: We overlapped in certain minor ways before I met him. I’d invent things on the sets of these films I’d do, but people didn’t want to change the dialogue as much as I wanted. There was a scene in Welcome to L.A. with Harvey Keitel and Sally Kellerman, my first film with real actors. And I was channeling Altman, so I’d say “Why don’t you say this and you say this?” The schedule was very tight, and we worked on it and tried to shoot it. Then Harvey says, “Alan, let’s do the scene as written. It really works.” We did it in take one, and that was the end of the scene. I still don’t know what it is. There’s a style to my dialogue you actually can’t easily improvise. On Choose Me, we changed a lot of stuff but not really. I was a little…not disappointed, but I kind of thought, “Oh, this will be more open-ended.” But it wasn’t, and I realized if I’m going to write these things, they’re going to follow it because they like it, I guess. Or it’s a different melody that they don’t usually sing.

Filmmaker: Is there something you invented on the set of Breakfast?

Rudolph: Oh, every day we’d invent. I never had a storyboard in my life. You come to a set with a crew, and it’s the same thing I said for every film I did: “Park the trucks over there and I’ll figure it out.” Because everything—the hangover, how you woke up if you did sleep—adds to it.

Filmmaker: Was there any conversation you had with either Elliot or your editor, Susie, about tone?

Rudolph: No. Elliot’s great. Soderbergh used Elliot after he saw the film we did and worked with him two or three times, then started shooting himself! Susie… I never wanted an editor to assemble anything. I want us both to start at scene titles, then we’d discover it as we go along. We had to make our own commercials most of the time on this movie. I would never allow product placement in my movies. They’d pay you money to put Coca-Cola in there. On Breakfast, I told [producer David] Blocker, “I’ll show any product. If they want to give us commercials, I’ll show them! I’ll have our actors talk about their product. I want the most commercialized thing we can do.” [We shot in] Twin Falls, Idaho. Every franchise in the whole world was there, but none of them would let us shoot. Pontiac wouldn’t let us use their name. We had to take all the logos off.

I’d never been to a Target in my life. We shot this in ’98. There was not much going on at Twin Falls, maybe there is now. There was one bar and grill. I always look for a bar and grill. That’s where we ate every single night. But I went into a Target one day to get something. It was enormous. Nobody was there except the goth kids. You’d look down an aisle and it would be forever, you were just looking for a bottle of water or something, and here would come three kids in long black gear, black eye makeup, black everything wandering up and down the aisle. I was waiting for George Romero to come out or something.

Filmmaker: Was this the most expensive movie you shot?

Rudolph: By my standards, it was really expensive. I think it approached $10 million. But we had time to shoot. It was a whole company on location. The actors didn’t get their usual rate, but they weren’t working for scale like on most of my films. I have a certain way of shooting. It’s all economic influence because we never had a lot of money, and because I believe the actors’ faces are the most interesting thing you could do to any film. Our equipment package is a dolly and a zoom and that’s it. I never asked for anything more than that. Never any special stuff, and never even hard lenses. The zoom will cover it. Long takes wind up on an actor’s face, because that’s usually the punchline of every scene I do. Elliot and I had worked a few times. When we did Love at Large, on the first day during the first shot, he turns to me and he goes, “Same old shit, huh?” I said, “I don’t know, I’ve never learned anything else, Elliot.” He said, “Don’t you want to get in there?” I said, “No.” So on Breakfast, I said, “Elliot, this is your dream picture. Get in there.” Handheld, wide angles, right next to their faces. He was drinking carrot juice all day long.

He’s the greatest operator. He started as an operator on a documentary I made about Timothy Leary and G. Gordon Liddy [Return Engagement]. That 16mm documentary cost more than Ray Meets Helen. On that one, there were kids who’d never been on a set before as the crew. The production designer was nailing down things like the backing. I said, “No, the whole point is you want these walls to move to the next set.” He said, “I’m making it permanent. This thing was moving!” There’s a scene where they have dog shit. They went out and got dog shit! I said, “No, you can’t do that!” So he said, “What are we going to do?” I said, “Figure it out!” He went to a chocolate store and got chocolate and it worked out. By the end, he was great. It was unlike anything. It was as close to teaching film school as I ever got, I guess. They didn’t have film school when I was at school.

When we timed [Breakfast for the re-issue], Elliot lives in the Bay Area and came to LA, and I did it by remote. He said, “You know, I haven’t seen the movie in a long time. We did a lot of stuff for the first time. The way it was edited, the way the things are happening. They’re commonplace now, but I can’t remember seeing any of this before this.”

Filmmaker; Something you clock into is that the car salesman is like the nexus of American conservatism. It is the absolute epicenter of someone trying to sell you false independence.

Rudolph: In Los Angeles there was a guy named Cal Worthington. He went to jail, too. The car commercials were out-commercializing each other, and I didn’t even stretch for those in Breakfast. These were things that I remembered as a kid. There’s something so symbolic about all of that. I don’t do the Internet movie review thing, but I’m sure if you look it up, you can’t find a good review by a major critic. And I’m sure audiences all hate it.

Filmmaker: It’s finding an audience now.

Rudolph: Well, most of them will be friends of my wife’s.