Back to selection

Back to selection

My Hot Librarian Summer: Libraries and Independent Film Distribution Strategies

It can take two or more years for independent films to progress through festival, theatrical, VOD, streaming and maybe airline releases, after which their discoverability fades. For filmmakers, the question then becomes, “How will people discover my movie now?” For many, the answer revolves around libraries. Across public, college and university libraries, there are estimates that up to 30 percent of library checkouts are movies, not books. Filled with DVDs, libraries have become the new Blockbuster—but, increasingly reliant on library-specific streaming services, they’re also becoming the new Netflix.

Many of us independent filmmakers are so excited to sign a distribution contract (any contract) that they fail to read the fine print. When it comes to the inevitable paragraph on “ancillaries,” most of us (and even our entertainment lawyers) glaze over the sections detailing topics like “physical media,” “non-theatrical” and “educational.” But there’s gold in those paragraphs. If you are an independent filmmaker with a distribution offer, before you sign on the dotted line, you should consider trying to hold back some of these rights. At the very least, ask your distributor if they have a clear strategy for what they plan to do with these rights.

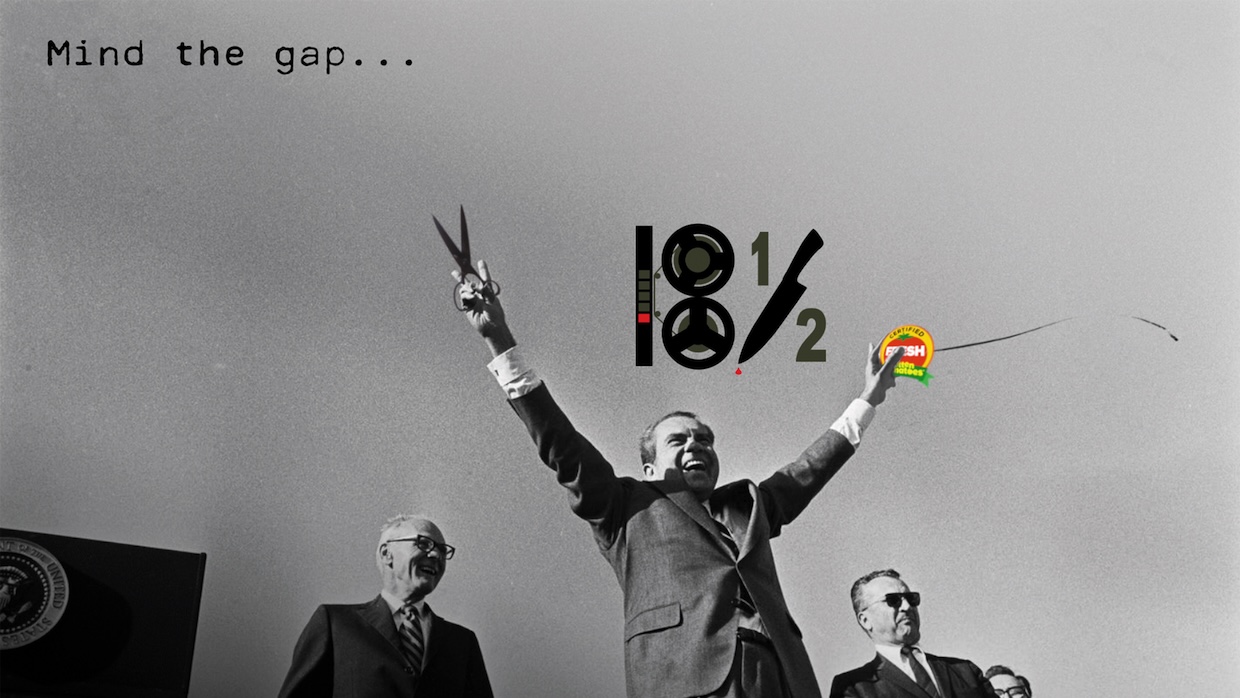

For my most recent film, the Watergate thriller/comedy 18½, we aggressively divided our distribution rights between several different U.S. and international distributors. One, MVD Entertainment, was tasked with handling our physical media in North America, but we carefully carved out educational rights for ourselves. As a result, my Brat Summer was simultaneously my “Hot Librarian Summer,” during which I approached public and academic librarians to learn how films wind up in libraries and, ultimately, in the hands of their patrons.

It All Starts with Your Contract

It’s important to understand the deep legal, linguistic and especially cultural differences between public libraries and academic libraries and how a savvy independent filmmaker can make the best of working with both, whether they have a distributor or are attempting self-distribution.

Public libraries in North America blossomed in the 18th century and expanded considerably in the late 19th century, thanks in large part to robber barons like Andrew Carnegie who were trying to buff up their civic images. But by the 20th century and on into the 21st, they were generally supported by municipal, county, state or provincial taxpayer dollars. Even the smallest towns and villages in the United States and Canada proudly boast a library, with bigger cities having scores of library branches across all kinds of neighborhoods. Far from just having stacks of books, modern public libraries have become true community centers that morph into classrooms for everyone from tots to grandparents, voting booths on election day, cooling centers during heat waves, sites for tabletop gaming and crafting, used bookstores, high-tech maker centers and tool, seed and even ukelele checkouts.

One facet of public libraries is that by definition they are open to anyone in the community and almost always offer their collection and services to their patrons for free. A more recent phenomenon is that public libraries are also on the frontlines of the culture wars in America. Attempts to ban books at public libraries (as well as school libraries) have radically increased in just the past few years, with significant censorship attempts in at least 17 states. In the small Iowa town of Vinton, the local public library had to shut down completely when the staff quit en masse due to harassment by anti-LGBT forces in town.

Academic libraries, on the other hand, are designed to be exclusive collections intended only for the college or university communities they serve—primarily students and faculty. So, in addition to individual use, academic library collections are often checked out by faculty in order to be shared with students in their classrooms. When it comes to films, that’s a key distinction between academic libraries and most public ones, where films are usually viewed by individuals only, not by groups.

One challenge with incorporating libraries into a film’s distribution strategy is that, depending on which sort of libraries and how they’re used, there are potentially several different buckets of rights they could fall into. If public libraries are buying a film for their patrons to use individually, those purchases are just part and parcel of either “physical media” rights (i.e., DVD/Blu-ray/4K) or general streaming or VOD rights, depending on whether or not that library uses a library-specific streamer, like Hoopla or Kanopy. Completely separate from that, if a filmmaker plans to do any one-off, community-based screenings that happen to take place inside a public library (common for many issue-based documentaries), then those are usually considered non-theatrical exhibition. But academic libraries and screenings at colleges and universities are a whole different kettle of fish that tend to fall under “educational” rights in most contracts. In all those cases, if there’s any ambiguity at all (and there usually is), filmmakers and/or their attorneys should contractually clarify these distinctions. Not certain whether non-theatrical exhibition includes library screenings? Make sure to spell it out when defining the term. Is it vague if “educational” rights include academic library purchases (as opposed to, say, on-campus screenings for classes or student groups)? If so, spell it out for clarity.

Let’s Get Physical (Media)

Physical media is where things get really interesting for libraries and where there is a unique opportunity for independent films in particular.

In the past few years, standard-definition DVD use has been dropping, almost to the point of the format’s obsolescence. Many studios aren’t even releasing films as old-school DVDs, instead opting for high-tech, high-priced, high profit margin 4K and UHD Blu-rays. But remember how everyone said vinyl records were dead, and now they’re the hottest thing in music retail? Something similar is going on in the home video world. Many of those rediscovering the joys of physical media are doing so because they are realizing they never really “owned” any films in the streaming world—or even those they “purchased” digitally. Streaming films are as fragile and fickle as Amazon or Netflix’s latest streaming model—or David Zaslav’s stock options at Warner.

This is where the demographics of public libraries start to explain why so many are still reliant on old-school standard-def DVDs. For one thing, many public library patrons don’t have streaming channels. Some are the elderly, who cling to their cords and can’t figure out this newfangled model of streaming subscriptions. Some are in rural America, where high-speed internet simply hasn’t arrived yet. Some are the economically precarious who struggle to put food on their plates, lacking the means to buy a 4K UHD player or a Netflix subscription—and that’s just for the people who check out movies and bring them back to their homes. Many library branches also have viewing stations for patrons but haven’t had the budgets to upgrade their own hardware in years. And with the long-ago demise of Blockbuster, the end of Netflix’s red envelopes and the more recent collapse of Redbox, there literally isn’t any other place people can “rent” movies. So why not “borrow” movies from their local public library, for free!

But if nobody’s renting, buying or subscribing to your film at a library, how can you actually make money on public library DVD sales? First, it’s worth understanding that almost every public library in North America buys its DVDs from a single source: Midwest Tape, an obscure company in the Toledo, Ohio, suburb of Holland. It’s a jovial operation that started as a video store in the 1980s and has since almost entirely captured the physical media market for public libraries in the United States and Canada. So, if a public library has a budget for movies, which almost all of them do, they just look at Midwest Tape’s weekly newsletter and order new DVDs/Blu-rays/4K UHDs from those listings. Midwest Tape, in turn, buys all those discs directly from either the studios or independent film distributors.

One look at the numbers explains why lo-fi DVDs still persist. Libraries essentially pay retail prices to Midwest Tape, not saving much more than buying them on Amazon or directly from distributors. But Midwest Tape offers unique added value to libraries by streamlining ordering, cataloging and even providing security labels. A library might pay Midwest Tape $12 for a DVD, $24 for a Blu-ray or $40 for a 4K of the same movie. If you’re a librarian with a fixed acquisition budget, your goal is probably to get the greatest number of movies that most of your patrons can actually watch rather than the highest quality movies that fewer patrons can watch. At the end of the year, you’ve got to justify those expenses to your local city council or county supervisor who’s approving your budget. So, if you’ve got a fixed monthly budget of $1,200, wouldn’t you rather buy 100 different DVDs than 50 Blu-rays or only 30 4Ks? And if you’re the purchasing librarian for a large county or municipal library system that may have as many as 40 or more individual branches, it behooves you to spread the wealth and buy the lower-tech movies that you can spread across most of your branches.

It’s true that most public libraries are tapering down their DVD collections, either starting to upgrade to higher-def physical formats or shifting entirely to streaming models. But at least for now, while it lasts, independent filmmakers are uniquely positioned to take advantage of this one particular market. If studios have already written off lower-priced DVDs, then independents are able to swoop in and capture the library market. Not answering to Wall Street investors and hedge funds, independents and their distributors can justify much smaller per-disc profit margins.

As a result, public library purchases can easily represent the lion’s share of a film’s total DVD sales. For 18½, public libraries accounted for a whopping 75 percent of all DVD sales, according to statements from our distributor, MVD Entertainment. We might be the outlier, but 18½ has been a bona fide hit in the public library world. One big reason is that the film was featured in Midwest Tape’s weekly PDF newsletter as one of five “staff picks” the week it went on sale. Their staff selected the film based largely on our good reviews, recognizable talent, PG-13 rating and subject matter that relates to an event people were familiar with: Watergate. Midwest Tape was able to sell over 830 individual DVDs to libraries in over 500 cities and towns in 46 states and five provinces, from Anchorage to Miami, Newfoundland to Vancouver. Many library systems bought multiple copies to distribute across many branches: 31 in Los Angeles County libraries, 34 throughout the Bay Area, 16 in St. Louis city and county libraries. You know what’s cooler than getting a film into the Toronto International Film Festival? Knowing that your film is in a staggering 34 individual Toronto library branches! (In comparison, only nine Toronto branches have copies of All the President’s Men, and that’s been rereleased on DVD or Blu-ray about five times over the decades.)

To be sure, you and your investors won’t get rich from library sales. But it isn’t just about the money. Many rural and underserved urban communities don’t have local film festivals, thriving arthouse theaters or robust streaming options. For them, the local public library may be the only way patrons can even watch your independent film, and librarians know that and are happy to focus their limited resources on independent films.

The other upside is that by getting DVDs into libraries across North America, independent filmmakers are essentially crowdsourcing archived versions of their films throughout the United States and Canada. In 15 years, when your distributor goes bust, your hard drive plugs are obsolete and earthquakes and floods have taken out the coasts, you’ll still be able to find a working, viewable copy of your film in the middle of Nebraska and Saskatchewan. Instead of paying a single facility to archive your film, you’re essentially getting paid by hundreds of archives. What’s not to love about that?

It’s All Academic

Unlike public libraries, academic libraries can’t get rid of their DVD collections fast enough. College and university libraries that once held vast stacks of DVDs are largely forgoing them in favor of streaming models geared specifically toward the academic market. That said, a considerable number of academic librarians I spoke to are starting to have buyer’s remorse about those decisions.

Academic libraries don’t just buy the film itself. Instead, they also usually buy the accompanying “public performance rights,” or PPR, which allow professors to legally show the film to their entire class all at once and may allow student groups to show the film as well. Instead of paying $12 for a DVD, most university libraries are accustomed to spending around $300 for the DVD that includes PPR. While a public librarian blissfully can spend $300 buying 25 different movies, a beleaguered academic librarian has to choose very carefully to buy a single film for the same price.

Consequently, most academic librarians limit their collections to films that a particular faculty member is requiring students to watch for a specific class. This might work out nicely for a niche documentary that dovetails with a commonly taught class at multiple schools. Professors happily assign docs for homework or, better yet, screen them in class and eat up half a period where they don’t have to lecture. But for fiction narratives, it’s much harder for professors to justify ordering them based on either the subject matter or the intrinsic value of the film. Even in film schools, most classroom assignments are for decades-old classics, rather than contemporary indies.

Meanwhile, the infrastructure for projecting films in college classrooms has changed dramatically in just the past few years. Ten years ago, a professor could walk into class, plug their MacBook into the classroom projector and slip a DVD into the built-in drive. Laptops with DVD players? Not so much anymore. Classrooms with hardwired DVD players started to crap out and weren’t replaced due to dwindling budgets. It’s become simpler and easier to just let the professor log onto either a library server, or better yet, an academic streaming company that licenses films to that school’s library. A couple clicks on the professor’s laptop, and voila! The students can watch Battleship Potemkin while the professor naps.

“Ten years ago, we still purchased hundreds of DVDs a year for films that were well reviewed or because they were just interesting,” one librarian at a top ten film school told me. “That is how we amassed a collection of over 8,000 DVDs. We probably only purchase 10 to 20 DVDs a year now and only for faculty requests.”

For a few years, many academic libraries hosted their own campuswide servers. Filmmakers and distributors could sell and upload .mov files directly to these libraries, which happily paid several hundred dollars for the PPR in perpetuity. Many would buy the DVD as well as streaming files. One documentary filmmaker I know made close to $50,000 just selling these digital files and DVDs to libraries.

Swimming Upstream

However, between the pandemic and changing streaming patterns, these internal library servers are becoming nearly as obsolete as DVD collections. Instead, most academic libraries are relying on academic-specific commercial streaming companies. As that film school librarian told me, “Now, instead of building collections ‘just in case,’ we acquire access ‘just in time.’”

There have been several players in the academic streaming world for years, most of which focused on documentaries (like Academic Videos Online, a product offered by the database Alexander Street Press, and Docuseek), and some more geared toward second-run studio fare (like venerable 16mm distributor Swank). To fill the void for narrative fiction films—older classics and newer indies, as well as many documentaries—Kanopy has quickly become the dominant streamer on campuses. Kanopy is now available in most North American college campuses and about a quarter of public libraries.

Meanwhile, Midwest Tape has Hoopla, the dominant player in the public library streaming space, available in more than 14,000 North American public libraries. Hoopla works similarly to Kanopy, and many of these public libraries have nonexclusive deals with both streamers. Hoopla and Kanopy also are expanding their global footprints, so you have to be careful in your contracts to stipulate clearly which territories you want covered (just North America, or other countries, too?). Like using a commercial streamer, once you’re a subscriber to either Hoopla or Kanopy, you can watch films on your own device easily and pretty much anywhere.

For academic libraries, Kanopy offers various ways for them to pay for public performance rights. One way or another, these “patron-driven acquisition” models mean that a library only pays for the rights to a film if a certain number of students or faculty watch it, then it resets back to zero and rolls over with each new semester. (When a modern librarian embraces or bemoans “PDA,” this is what they’re likely referring to, not students smooching between the stacks.)

But some libraries are balking at these price structures. If three students watch a film, the streamer might charge the library $150 per semester. Some schools are specifically telling students and faculty they must get permission before watching a film, or that they need to “request access” and justify how or why they want to watch it. Likewise, some public libraries limit patrons to a certain number of Hoopla movies a month.

Another pitfall is endless license fees for a regularly taught film. If an Intro to Film class screens The Godfather every single semester, the library could be paying $300 each year for the next 20 years. Compare that to a one-time $300 perpetual PPR license for a DVD or downloadable file. Library costs for streaming films are ballooning just as their budgets are cratering. This dissatisfaction has led to a rise in more affordable options for academic libraries, like upstart streamer Projectr, which is being embraced by academic libraries (CalArts, Duke) and public ones (like the New York Public Library).

One other downside to academic streamers (not to mention commercial streamers like Netflix) is that they don’t typically come with all the fun bonus features, behind-the-scenes documentaries and commentary tracks that a typical disc might have. For film students in particular, eager to find out how a given film got made, this is a big problem with the shift away from physical media. And for filmmakers, sharing the inside struggles of our process is often as much a part of our creative expression as the films themselves. On our 18½ DVD, for example, we have an almost two-hour-long BTS documentary called “Covid 18½: The Making of a Film in a Global Pandemic.” Naturally, it’s a half hour longer than our feature itself and, at least for now, it’s only available on our physical disc.

Unfair Use?

Some other academic librarians are taking a different tack by buying cheap DVDs and refusing to pay the three-figure public performance rights out of principle, spite and/or sloth. Some of these librarians adhere to a reading of US copyright law that in-class screenings of films are tantamount to “fair use” as long as the films were otherwise sourced legally. Therefore, they don’t need to pay the filmmakers for their hard work, labor and creative artwork, even if they’re showing the film in a lecture hall with 500 students. But just because they can use fair use, does that mean they should?

It’s one thing if a professor or librarian can’t find an existing distributor or a living filmmaker behind an obscure East German fly fishing documentary from 1972. But when it’s abundantly clear that the filmmakers or their designated distributor are actively selling public performance rights for their film, many contend that schools have an obligation to make best efforts to acquire those rights and pay fairly for them.

When a financially strapped community college serving first-generation students buys your DVD straight from Amazon for $12, it’s more understandable. But when a university with a $21 billion endowment buys your cheapo DVD and happily sloughs off your $300 public performance fee, it also sends a self-defeating message to its own film students. Film schools and film studies programs might want to work with their own libraries to cultivate a more sustainable ecosystem for professional filmmakers.

For filmmakers, all this instability, competition, anger and resentment among academic librarians struggling to survive can still provide opportunities. Kanopy and Hoopla are happy to talk to individual filmmakers, although ultimately they prefer to make deals through established distributors (which might easily take 30 percent off the top or charge a couple thousand dollars for a set-up fee). Some filmmakers have made good money through Kanopy, but for others, just being listed on Kanopy doesn’t actually mean people are watching the film or that money is changing hands. And if your educational or library streaming deals are through one of your distributors who’s already paid your minimum guarantee or otherwise has creative or lax accounting, you might still never see a dime.

Remember, “educational” rights encompass one more thing: in-person live screenings on campuses. Many film departments, student clubs and other on-campus groups might well pay in the range of $200 to $500 for a screening fee, which you can often combine with guest lecture fees, flights, accommodation and meals. It usually takes a lot of planning to pull off these screenings, but according to filmmaker Betsy Kalin, campus tours for her documentary East LA Interchange provided a sustainable income for several years and eventually inspired her to become a film professor. Sometimes you can combine campus screenings with film festival screenings in the same city and walk away from a film festival with money in your pocket. For 18½, we’ve had about a dozen in-person educational screenings in the past few years, and because of them, we actually made money on our film festival tour.

But again, it’s not all about the Benjamins. From Greenwich Village to Palo Alto, with stops in New Jersey, Indiana, Miami, St. Louis and Iowa, I happily can say that 18½ is already in the permanent collection at “top five” film schools, Ivy League institutions, upper-crust private universities, public state schools and smaller colleges across the country. As independent film producer Mike Ryan has said, sometimes “cultural capital” is more important than actual capital.

Where does that leave the savvy indie filmmaker? On balance, it still behooves you to keep your educational rights for yourself as best you can and for as long as you can. It’s not rocket science, but it is a lot of time to try doing any of this yourself. I spent most of my Hot Librarian Summer sending three personalized emails apiece to 1,490 academic librarians at about 880 colleges and universities throughout North America (and yes, I had the dutiful help of a college intern). Just figuring out which librarian to contact is half the battle. At academic libraries, it’s sometimes the “electronic resource librarian,” sometimes the “liaison to the film department” or often someone with an entirely different title who has the authorization to buy your film.

While the conversion rates of DVD and streaming sales were only about one percent of all those emails, that still meant that we netted more money on academic sales than on all those 830 public library DVD sales put together. And for many of those other 99 percent of librarians who didn’t buy the DVD or streaming file, they were still valuable conversations to have. Now, when Kanopy does release our film (which I’m happy to say will start in mid-December), I’ll have a handy-dandy list of librarians to contact whom I know are eager to order 18½ that way. If there’s one thing I’ve learned, be kind to your neighborhood librarian!

Editor’s Note, 1/20/25: This article has been changed after publication. Midwest Tape sales figures have been updated, and the section, “Unfair Use,” has been expanded and clarified.

Dan Mirvish is a filmmaker, author, educator and cofounder of the Slamdance Film Festival. For more info on his film 18½ and how to buy or borrow the DVD from public and academic libraries, go to www.18andahalfmovie.com. For more on Dan go to www.DanMirvish.com.