Back to selection

Back to selection

Further Thoughts on Panasonic 4K GH4 – Updated

Tetraphobia is the east Asian practice of avoiding the number 4 because it sounds like the word for death. But to ignore 4K would be certain death for any manufacturer serious about digital motion imaging. It was only a matter of time before Panasonic dropped the other shoe.

Overcoming their fear of 4, Panasonic on February 6 announced the GH4, their first 4K/Ultra HD camera and portent of Panasonic 4K cameras to come. Formally known as LUMIX DMC-GH4, it arrived mere weeks after CES in Las Vegas, where Panasonic unveiled a prototype 4K “GH Next.”

Of course 4 can also bring good luck. Think clover.

Quite a few websites already contain detailed descriptions of the GH4 and its specs. One of the best is EOSHD. Most are reworked versions of Panasonic’s press release like DVX User, which nonetheless provides a handful of links to impressive test shoots, particularly this one.

In this blog I won’t attempt to list or tout every attribute of the GH4. It is, after all, a single-lens mirrorless camera for stills which secondarily permits capture of HD and 4K/Ultra HD video. (Panasonic calls it “hybrid.”) I’m only interested in the motion images it creates and advantages it conveys due to compact size and disruptive price.

I shoot often in the real world, meaning that practical design considerations like ergonomics, lens mounts, viewfinders, controls placement, and connectors are as important to me as abstract digital specs. I’ve spent the last nine months shooting different flavors of 4K and Ultra HD and now have a good feel for basic issues of these formats too.

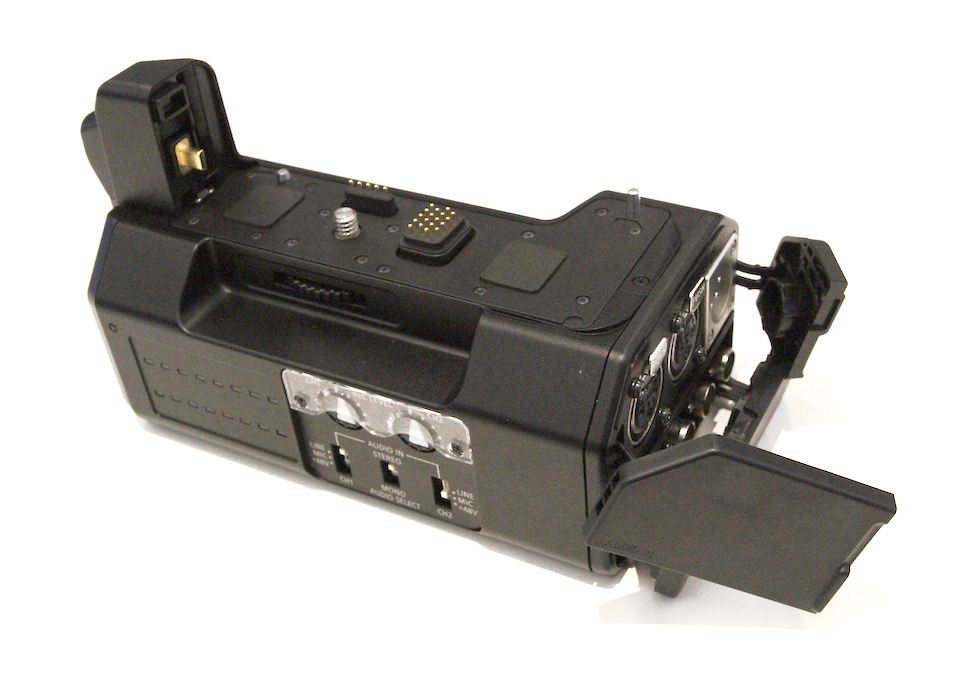

Below, after these notes, are photos I took illustrating the GH4’s design. You might want to glance at them before continuing, to get a sense of what the GH4 and its optional DMW-YAGH “Interface Unit” look like. Bear in mind that this GH4 and Interface Unit are working prototypes, about 70% complete per Panasonic. Audio controls on the Interface Unit are obviously unfinished.

Here’s what I think is important to know:

• The GH4 looks exactly like the GH3. Controls are virtually identical. Size too, a mere 1/3 ounce heavier.

• On March 10, Panasonic announced May availability for the GH4 body and DMW-YAGH Interface Unit, an optional breakout module for pro video connections (“Video Adapter for cinematography” in the press release). Effective price for the body is $1700 and video adapter, $2000. ($1698 and $1998 at B&H, for example.) The popular GH3 will remain a current product. ($998 at B&H.) On a side note, Blackmagic Design’s 4K camera, just now shipping, has dropped $1000 to $3000.

• GH3 and GH4 each incorporate a CMOS sensor with 16.05 active megapixels. Each utilizes a 4-CPU Venus Engine, Panasonic’s image processing and control computer. (Branding of camera CPUs for marketing purposes is a trend borrowed from Intel’s playbook.) However Panasonic says the GH4’s sensor and Venus Engine are “new” and “newly developed.” It should come as no surprise that the GH4 requires a faster Venus Engine to handle processing, encoding, and output of 4K signals. But clearly Panasonic has put in place the basic architecture for a durable camera platform.

Together the GH4’s upgraded CMOS and Venus Engine reduce rolling shutter with a pixel read-out twice as fast as the GH3. They capture and encode 1080/60p to ALL-Intra H.264 at 200 Mbps, a big leap from GH3’s 72 Mbps. Color reproduction and dynamic range are said to be improved too, even though ISO in motion picture mode still tops out at 6400.

• The GH4 is strikingly compact, an ideal complement to a Freefly Systems MoVI handheld stabilizer, an octocopter or drone. Designing the smallest possible digital single-lens mirrorless camera (DSLM) was Panasonic’s goal in co-developing the Micro Four Thirds format. Sony, by comparison, retained full-frame for their DSLM, the impressive Alpha a7R, equally petite but offering only rudimentary HD compared to GH4’s manifold HD and 4K recording options.

• The scaled-down Micro Four Thirds (MFT) sensor results in significantly narrower angles of view when using conventional full-frame or cine Super 35 lenses. Which is why a good case can be made for substituting a set of compact, dedicated MFT lenses.

When shooting 4K, for example, why saddle a GH4 with a heavy PL-mount lens and adapter when the MFT sensor can’t see half the image to begin with?

Huh?

Turns out the GH4 “windows” to obtain a 4K image. Its MFT sensor provides 4608 active horizontal pixels, more than the 4096 needed for 4K (Ultra HD = 3840). So the GH4 simply carves a 4K image from the center of the its sensor.

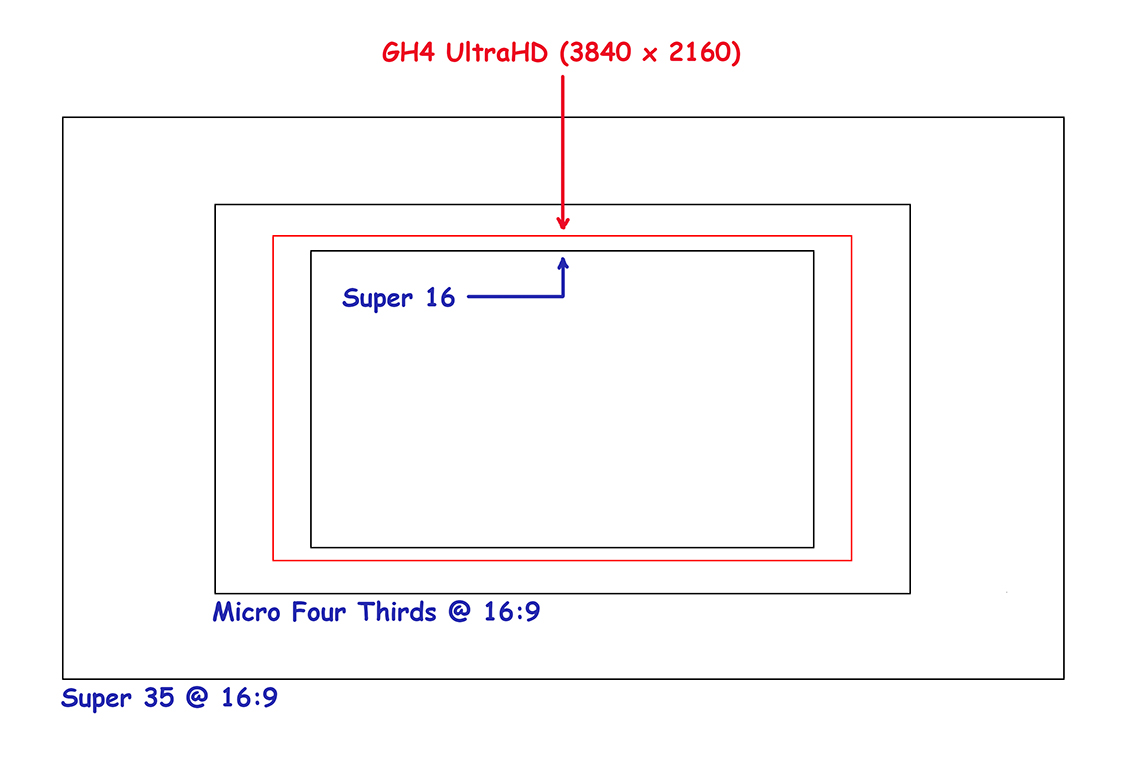

The illustration below compares Super 35 cropped to 16:9 with the GH4’s considerably smaller MFT sensor also cropped to 16:9. (Full MFT sensors are always 4:3). The GH4’s even-smaller 4K image is depicted in red. (To better match aspect ratios, I’ve depicted Ultra HD, 3840 x 2160, instead of full 4K, 4096 x 2160.)

I’ve also indicated the relative size of Super 16 film. Not that I’m saying Super 16 lenses will cover the GH4’s 4K, but you get the point.

(I could also have depicted the relative size of the unconventional 2.5K sensor in Blackmagic Design’s Cinema Camera, which fits exactly halfway between the GH4’s Ultra HD and Micro Four Thirds @ 16:9. To DPs like myself, who know the angle-of-view of Super 35 lenses by instinct, this proliferation of sensor sizes is dizzying if not counterproductive when swapping lenses under pressure.)

• 4K requires you to up your game when it comes to lenses. You will want to use the best lenses you can lay your hands on. Since the GH4’s 4K window comprises, in effect, a small format, you will want to be cautious about using lenses designed for larger formats, just as we were back in the days of 16mm. A lens that might suffice for capturing 4K to a much larger sensor might lack the same punch when used to capture the same 4K resolution to a sensor area half the size.

• The GH4’s small 4K window introduces an obvious advantage, however, and were I Panasonic, I’d bang this drum loudly when marketing this camera. Simply put: significantly more depth of field. If you think narrow focus was challenging when shooting HD with DSLRs, wait until you try 4K. 4K is either sharp or it isn’t. All that extra-fine resolution makes this new fact of life painfully apparent on the big screen. And while it will always be the case that on the tiniest screen –– your camera monitor or viewfinder –– everything looks happily in focus, which would you rather have when shooting 4K for documentary or sports: more depth of field, or less?

• Panasonic says the triple threat of faster Venus Engine, advanced imager, and newly-tuned Optical Low-Pass Filter (OLPF) raises the fine-detail filtering limit by 5% while keeping the lid on moiré and stair-step aliasing. This is a balancing act at best. Each of the GH4’s three sensor windows — full Micro Four Thirds with 16.05 Mpixels for stills, 16×9 crop downsampled to 2 Mpixels for HD, smaller 4K/Ultra HD window with 8.3 Mpixels — imposes different spatial sampling, requiring a different OLPF cut-off to avoid visible moiré. Such are the compromises of multi-format digital cameras.

• The GH4 bumps its OLED monitor resolution from the GH3’s 614K pixels to 1,036K. Likewise, OLED viewfinder resolution is raised by a third, from 1.74 to 2.36 megapixels. As a result, the GH4’s viewfinder is stunningly snappy and clear. Also new are peaking, color included, as well as 2x and 4x magnification. All the better to focus 4K with!

• The faster Venus Engine enables a new rapid autofocus system called DFD (Depth from Defocus) which operates in tandem with conventional Contrast AF (autofocus). For DFD to work, LUMIX interchangeable lenses are required, because the GH4 utilizes knowledge of the out-of-focus image characteristics of each lens, stored in the camera as part of the DFD system. To calculate focus, the GH4 analyzes bokeh (out-of-focus points of light) on the fly. The resulting autofocus is super-fast and controllable by finger from the 3-in. touch-screen monitor.

I think DFD is of limited interest for motion images. If you’re not using a LUMIX lens, forget about it. (There are 22 to choose from.) More to the point, DFD has an abrupt, impetuous quality which is OK given the instantaneity of capturing stills, but would, I think, be hard to finesse while shooting motion. Not that in principle I’m against autofocus in a world of large sensors and razor-thin focus…

• If you wish to know every format GH4 will record, such charts are all over the Internet. Suffice it to say that Panasonic has leveraged some of its broadcast technology in this camera: high profiles of MPEG-4/H.264 and selectable MOV or MP4 container formats. Selectable system frequencies of 59.94Hz, 50Hz, and 24Hz make GH4 a world-cam.

Ultra HD (3840 x 2160) is interframe (IPB) at 100Mbps at 29.97, 23.98, 25, and 24 fps. Full 4K (4096 x 2160), which Panasonic labels “C4K” (I like this designation), is available at 24 fps only.

HD at the high end is intraframe (ALL-Intra) at 200 Mbps, at all basic frame rates up to 59.94.

Recording these internally dictates a blazingly fast SD card. Specifically a SDXC UHS-I Speed Class 3 card with a minimum sustained write speed of 30MB/s (240Mbps), which Panasonic previewed at CES. You won’t find them at B&H yet, but I did locate a 64GB Kingston on Amazon with a street price of $133. I’m guessing 64GB is roughly 80 minutes of 4K. Which Panasonic says you can shoot continuously, no 4GB or 29:59 time limits. (At least not in the U.S.)

OK, I’m impressed.

For 1080p only there are variable frame rates for slo-mo and fast motion, up to 96 fps — your choice of 100Mbps or 24Mbps (AVCHD) — plus interval recording for time-lapse and single-frame for stop motion animation.

• Everything that GH4 records to an SD card is 4:2:0 8-bit, including 4K. What if you prefer 4:2:2 and greater tonal resolution a/k/a bit depth?

GH4 provides options to record them externally. There’s a micro HDMI port on the side of the camera. (The teeny tiny HDMI, not what anyone would describe as a rugged field connector.) When recording 4:2:0 8-bit to an SD card, GH4 can simultaneously output 4:2:2 8-bit via HDMI for either monitoring or external recording.

When not recording internally to an SD card, GH4 can output 4:2:2 10-bit via HDMI for monitoring or external recording. Up to and including 4K!

Indeed, Panasonic’s HDMI specs include 4K at 59.94 fps, which implies an HDMI 2.0 cable. An HDMI 1.4 cable should work for lesser frame rates. Incidentally, when outputting 4K via HDMI for monitoring, GH4 can downconvert to 1080p.

• And if a delicate micro HDMI port makes you nervous? That’s where the DMW-YAGH Interface Unit enters the picture. As you can see from the photos below, it connects to the micro HDMI port and creates a pass-through to a full-size HDMI connector on its side.

If reliance on any HDMI connector makes you nervous, the DMW-YAGH also offers HD-SDI outputs –– four of them. Also two XLR inputs for audio, a BNC input for external timecode (multicamera shoots), and a 12V DC input for battery power.

Here’s where things get uncertain. A Panasonic illustration of GH4 in a possible high-end production setup shows an AJA Ki Pro Quad recording 4K to ProRes 4444 — a good thing, in my book. The Ki Pro Quad is shown ingesting 4:2:2 10-bit 4K from a DMW-YAGH by means of “HD-SDI x 4,” a quad link. In other words, four HD-SDI cables. This implies four uncompressed HD signals, each a quadrant of the 4K image. Otherwise why would four links be necessary? Which raises the question, why wouldn’t DMW-YAGH use 3G-SDI, carrying twice the signal payload of HD-SDI?

Elsewhere the four HD-SDI outputs are touted as “4-system,” able to output parallel 4:2:2 10-bit HD signals to four devices at once. Which could be quite useful at times. We’ll learn more about the DMW-YAGH’s capabilities eventually, but I do know that signals over HD-SDI include embedded audio and timecode. Again, a good thing.

• Panasonic says GH4 in “Creative Video” mode offers two CINE-LIKE gammas, D and V. I have no clue what these letters represent, however two gammas with the same name are found in the AF-100. The AF-100 operator manual describes each as “a gamma curve designed to create cinema-like images.” What could be clearer?

• Final comment: don’t lose sight of the fact this camera is like a mini-DSLR in terms of form factor. Ergonomics for handheld shooting is not GH4’s strong suit, especially with any lens larger or heavier than Micro Four Thirds. At least GH4 is mirrorless. The viewfinder is live at all times, good news for those who prefer to hold a viewfinder to the eye. Although a big floppy eyecup would be a big help.

Stay tuned next for Panasonic’s 4K Varicam with Super 35 sensor, previewed recently at trade shows in Europe and Japan. With a silhouette resembling a Sony F55. Expect a big splash in April at NAB.