Back to selection

Back to selection

Ghost of a Ghost: Alain Gagnol on His Animated Noir Feature Phantom Boy and Co-Director’s Jean-Loup Felicioli’s Designs

Phantom Boy

Phantom Boy Heroically serving as a lifeboat of ingenuity and sophistication while a flood of CG talking animal features drowns the animated landscape, GKIDS offers uniquely conceived, handcrafted and thoughtful storytelling in a medium that has often reached its greatest potential through the pencils and brushes of those seeking to create art rather than doll-selling tentpoles. The independent animation distributor has eight Academy Award nominations under its belt, and few companies in field have remained as truthful to their mantra as these New York-based dream confectioners.

Earlier this year GKIDS released in the States the acclaimed, Paris-set steampunk adventure, April and the Extraordinary World. The distributor’s summer release is Phantom Boy, a stunning new 2D work that’s the latest production from French directors Alain Gagnol and Jean-Loup Felicioli, whose feature-length debut, A Cat in Paris, earned them a well-deserved Oscar nomination back in 2012.

Half otherworldly fable and half crime thriller, Gagnol and Felicioli’s sophomore effort expands their groundbreaking brand of noir-infused hand-drawn and hand-painted animation to American shores. New Yorker extraordinaire Leo, a charming 11-year-old boy, is suffering from a terminal illness when he discovers he can leave his weakened body in the form of an invisible apparition that can fly through the city for a few minutes at a time. Such mysteriously created recreational power proves to be a remarkable asset when a disfigured villain known as The Face, his yappy dog, and inept henchmen threaten to cause havoc in the metropolis. Working as a skillful informant, the young phantom partners up with injured New York City cop Alex and Mary, a fearless journalist, to halt the villain’s narcissistic antics — he really wants the world to know what happen to his once beautiful face.

Frame after frame, the film carries the imprint of the painstaking and labor-intensive technique. Lines filled with a nostalgic yet effective color palette construct a timeless world with measured suspense and whimsy. Flying around between buildings is stylish, graceful an electrifying all at once.

Intriguing and cleverly executed, Phantom Boy is an animated sensation imagined by the spiritual disciples of Hitchcock and Picasso and filtered through the prism of Marvel’s most iconic comic books. Its pastel-tinged Manhattan, fluorescent spirituality, one-of-a-kind design, thematic maturity and elegantly astute humor set it stratospherically apart from ordinary studio tales. Craftsmanship marries a genre-bending narrative for a glowing brainchild of a film.

Encouraged by Leo’s valiant curiosity I interviewed co-director Alain Gagnol about this utterly human story about a smiling ghost. Phantom Boy opens Friday, July 15, in New York at the IFC Center.

Filmmaker: Both A Cat in Paris and Phantom Boy borrow thematic elements and carry the tone of classic noir thrillers. Do you feel like you are creating a new genre of animation, let’s say, “French Animated Noir,” by reinventing these classic genre conventions?

Gagnol: The choice of film noir comes from my film references. Some American noirs had an enormous influence on me, films such as White Heat by Raoul Walsh, The Night of the Hunter by Charles Laughton and Kiss Me Deadly by Robert Aldrich, to name just a few. I am also the author of a number of noir novels for adults. When I wanted to write A Cat in Paris, the film noir atmosphere came naturally to me.

Filmmaker: Why do you feel the need to channel these crime thriller elements into animated adventures centered on children protagonists?

Gagnol: I realized that during the film noir era, animated films did not exist. This made the project even more interesting. I am a great fan of genre films (fantasy films, thrillers, science-fiction) and for me, the young audience is not a sub-audience. With children, you can be as creative as with adults. It seems to me that this is even an obligation because we are shaping the critical sense of future adult viewers.

Filmmaker: Phantom Boy tackles difficult subjects, such as the possibilities of terminal illness and life-threatening violence. We rarely see these ideas in American animated films. Can you talk about how you handle them and still make a film that’s accessible for a young audience?

Gagnol: Children are an audience that should not be underestimated. Unlike adults, they are not afraid to broach serious subjects. It’s possible if it is done without making the film distressing. Phantom Boy is about a sick child who battles and triumphs over his illness. That is the most important point. In this way, we are telling children that with courage you can withstand the most difficult hardships.

The violence is not realistic in the film, otherwise it would be shocking for children. The gangsters who are scary are also the most ridiculous characters. A scene of suspense is generally followed by a gag which makes the sequence less alarming. This shows that being afraid in the cinema is a game.

Filmmaker: With your two films as directors you have developed a unique visual aesthetic that’s different from other animated films in France and abroad. What are some visual inspirations for the stylistic approach in your film? Where does the style come from?

Gagnol:The film’s graphic aspect comes from Jean-Loup’s work. He studied at the School of Fine Arts and intended to become a painter. As a result, his influences come from classical painting. In his drawings you can find influences of Picasso, Modigliani, Bonnard, Flemish painting and numerous others. French and European comic strips also inspire him a lot.

Filmmaker: How has your work as animators in the film Raining Cats and Frogs (La prophétie des grenouilles), of which I’m a big fan, shaped your sensitivities and artistic interests in terms of what you went on to do in your features as directors? What did you learn from working on that film?

Gagnol: I began working as an animator at Folimage. It taught me to consider the characters in an animated film as actors. They must express what they are and what they feel. As a scriptwriter, it also helps me a lot to really know what animators do. I would not write the same scenes in the same way if the screenplay was intended to be made with real actors.

Filmmaker: A Cat in Paris highlights that city in a particular way; on the other hand Phantom Boy takes place in New York. Can you talk about the differences in creating backgrounds, buildings, and architecture in these two films? Was it very different to draw Paris than to draw New York?

Gagnol: Jean-Loup created all the design drawings and supervised their color layout very closely. In our films, Paris and New York are both equally unrealistic. These two cities are like dream versions, as if they had been recreated in the studio. The biggest difference was the number of windows. After having drawn thousands, Jean-Loup called New York “the city of windows.”

Filmmaker: Now that you work as directors do you miss being more hands-on in terms of animating? How much animating do you get to do in this film if any at all?

Gagnol: In fact I had the time to do some animation on the film. I took care of the main shots where we see the Phantom Boy fly. I wanted to give him a particular style, a way of moving that I had created using Jean-Loup’s drawings as my inspiration.

Filmmaker: What are some of the key roles for a director of a smaller independent animated feature like yours? How do you divide labor between the two of you?

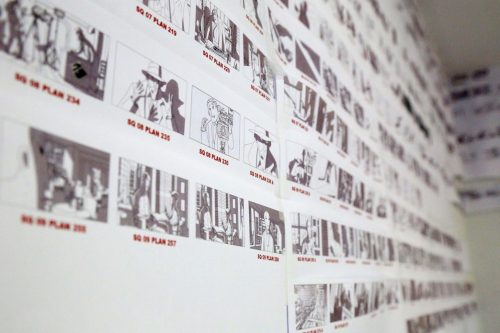

Gagnol:I’ve worked with Jean-Loup for twenty years now. We made 14 short films before doing A Cat in Paris. This enabled us to invent a method that suits us. We have applied this method on a bigger scale in order to make our feature films. The breakdown of roles is as follows: I write the screenplay, Jean-Loup creates the graphics. I do a quick preliminary storyboard in order to put the production in place, and Jean-Loup draws the final storyboard with the right graphics and the changes that become necessary during the cutting. Together we then supervise the work of the teams.

Filmmaker: Tell me about your team of animators at Folimage. What are some of the benefits of working an independent studio, and what are some of the struggles that come with those benefits? Do you feel that there could be benefits from working at a larger American studio?

Gagnol: The greatest advantage for us is working with people we know and who know us. This makes it possible to develop everyone’s team spirit and involvement. They are used to our films and know what we want. Jean-Loup’s graphic style does not lend itself well to animation, it is difficult to master. We are not looking for spectacular, virtuosic animation, but a personal style. Despite everything, the animation must remain precise and sensitive. This is not always easy to explain to animators who have more classic ways of working. The strength of American studios comes from their impressive know-how and their budgets, which cannot be compared with ours. We are obligated to do as best we can with limited resources, which prevents us from being as perfectionist as we would like to be.

Filmmaker: When you make the original French version of a film you select the voices that you feel fit the characters. Do you have a say in the process of dubbing into other languages? Do you feel like your films change depending on the language, or does the fact that they are animated help them be universal?

Gagnol: We do not participate in the choice or the direction of the actors for other languages. It would be difficult for us to direct an actor in a language we don’t know. The intonations are very different from one country to another. Animation is a very universal form of cinema. It is almost magical. We can become attached to objects, to animals, and feel emotions with them. When I see one of my films in a foreign version, since I know the dialogue by heart, I have the impression of understanding everything!

Filmmaker: Tell me about the creation of Leo, the brave hero in Phantom Boy. Where does he and this story come from? What was the process to designing him and his phantom?

Gagnol: I wanted to film a character that we almost never see on the big screen: a child with a bald head due to a serious illness. It is always interesting, as a filmmaker, to show viewers an image to which they are unaccustomed. This is even more so in the case of children who, out of tactlessness or ignorance, can be very cruel with other children who look different. When this type of character is used in cinema, it is generally in sad and dramatic films, in melodramas. This is an action film, with gags, and the illness, even if it is very important, is only one element among others. It does not totally define the character who retains his freedom as an individual. Graphically, Phantom Boy has darker colors than the other characters. He is like a less present version of reality, as if he were hidden behind a transparent curtain. On the design level, it is very powerful to have a bald child. This suddenly gives him a strong presence and a strangeness.

Filmmaker: The other characters are also incredibly memorable: the villain and his pet, the detective and the journalist. What was the process of creating and designing these?

Gagnol: When I create characters, I don’t give them a physical description. This leaves Jean-Loup with great freedom to create. For example, for the man with the broken face, he was described in the screenplay as disfigured. The first attempts were realistic and he was really horrible to look at. Since this is an important character often present on the screen, Jean-Loup wanted him to be handsome, despite his disfigured face. So he found his inspiration in Picasso’s cubist paintings in order to find a visual translation of his handicap.

Filmmaker: Throughout the entire animation process of Phantom Boy what were the most challenging aspects, images, or sequences to realize?

Gagnol: The most delicate part for us is to keep the graphics. As I said, Jean-Loup’s drawings are very difficult to animate, they don’t lend themselves to it easily. The almond-shaped eyes tend to squint very easily. The outlines of the characters must not be too round. Otherwise they soften, and there are many other problems. But I think the most difficult aspect remains time and budget management. We have to adapt our requirements if we don’t want to endanger the film. We spend a lot of time waiting for the film to be financed, and once that’s done, we have to hurry to make it.

Filmmaker: Could you describe your intention and approach to the color layout? Leo’s fluorescent silhouette contrast beautifully with the pastel colors that permeate the frames.

Gagnol: We wanted to show that he was becoming weaker. He seemed to us a silhouette void of colors which made it possible to illustrate the idea that he was losing his substance. As if he was becoming the ghost of a ghost. There was also the idea of his disappearance in the form of flashing lights. This sequence takes place in very dark colors. The luminous color blue makes it possible to create a strong contrast with the rest.

Filmmaker: How much 3D animation and effects where used on the film and why were these important or necessary to the story?

Gagnol: It was very important to make New York alive by populating it with pedestrians and cars. This would have been extremely long and costly if we had to draw everything by hand. So we had the pedestrians and the cars modeled by computer. This was possible because they are only details within the frame. The viewer sees them but doesn’t specifically look at them. Otherwise this would have created problems of consistency with the rest of the film which is entirely hand-drawn. We also used 3D for the cargo since it was simpler. We added the hand-drawn animation (smoke and fire) over it.

Filmmaker: Can you briefly talk to me about your process of creating the storyboard for Phantom Boy, given all the flying and action sequences in it?

Gagnol: Over the years we have created a production style that fits Jean-Loup’s drawings. For example, there is very little camera movement. This is due to the fact that the shots are conceived as tableaux or illustrations, and that, above all, we want to keep the composition of the image. Usually, in films about superheroes, the camera accompanies the character when he flies. We did the opposite. The camera remains fixed and Phantom Boy flies by in front of us. This increases the impression of softness and of dreaming, as if we were a witness watching him pass by from our window.

Filmmaker: In terms of the sound design and music, how do you feel these complement the visuals and what was the process to create them?

Gagnol: I’ve always thought that in a film the sound (music, ambient noise, sound effects) was as important as the image. You really become aware of this when the film is made. As long as the sound isn’t there, the film is not yet alive. Even if the images are really beautiful, it’s not enough. The sound gives the impression of reality, especially in an animated film where everything is recreated. We have worked with Serge Besset, the composer, since our first short film. He has a tremendous capacity for creation and adaptation. He has also perfected composing music for animated films. We work with him for a good part of the filmmaking, which makes it possible to create the images and the music at almost the same time.

Loïc Burkhardt is responsible for the creation of ambient sound and certain special effects. We have also worked with him for a very long time. His demanding nature always enriches our films.

We also asked a New Yorker to record real street sounds on-site, in order to have a realistic feeling of the city.

Filmmaker: What would you do if you could have Leo’s ability for a day? What would you investigate or try to figure out if you could be a phantom flying through the city?

Gagnol: The feeling of flying must be so extraordinary that I think I would spend my time gliding above the clouds!