Back to selection

Back to selection

The Vocation of the Storyteller

Is independent filmmaking a calling, like a religion? The Rev. Megan Hollaway looks at the religious impulse in Todd Rohal’s priest comedy, The Catechism Cataclysm.

Todd Rohal’s The Catechism Cataclysm, released by IFC Midnight, is a metaphor for filmmaking and a love letter to lonely priests. It is a film about the X-rated nature of faith in God, though it masquerades as a superficially satanic parable. And it’s about the high stakes of storytelling — central to priests and filmmakers alike.

But I’m an Episcopal priest and tend to read God into everything. It’s a hazard of the job. You might decide Catechism is a drug-induced midnight movie or a scatological horror-comedy.

So just indulge me here.

Catechism so thoroughly mixes up the spheres of faith and film, priest and filmmaker that it is hard to tell where one stops and another begins. This holds true both for the movie itself and for the experience of making it — as I discovered after a few conversations with Rohal.

So in the spirit of getting our spheres mixed up, what follows are some thoughts about the film, the theological nature of storytelling and the vocation of the filmmaker.

Stories, X-Rated Faith & Father Billy

There is a reason that stories, more than any mode of communication, are the best way to talk about God. They can’t be reduced; they shouldn’t be explained away; they have the power to captivate us; in a word, both stories and God are mysteries. If you’re not accustomed to thinking about God very much, this might be helpful:

God is the mystery of why there is something and not nothing.

Having faith in God, or stories or both means trusting something you can’t fully comprehend. They are both, by their very nature, inexplicable. It’s no wonder that at some point there will come a crisis of faith — a time when it becomes difficult to say “yes” to the God or story that has captivated you.

We meet Father Billy in just such a crisis. Played by Steve Little with expert daffiness, Father Billy is a young, nearly unhinged Catholic priest. At the beginning of the film he’s at a Bible study telling his parishioners an urban legend — the kind that is circulated exponentially on the Internet by people who don’t already get enough e-mail. He seems to break every rule of good storytelling: the characters are generic, the plot is trite and predictable, he forgets his audience, and then he compounds his error by explaining the story he’s just told.

His parishioners endure it, trying and failing to bring the conversation back to something more meaningful. His superiors decide it’s the last straw. The antic earns him a forced sabbatical, which he decides to spend with his sister’s ex-boyfriend from high school.

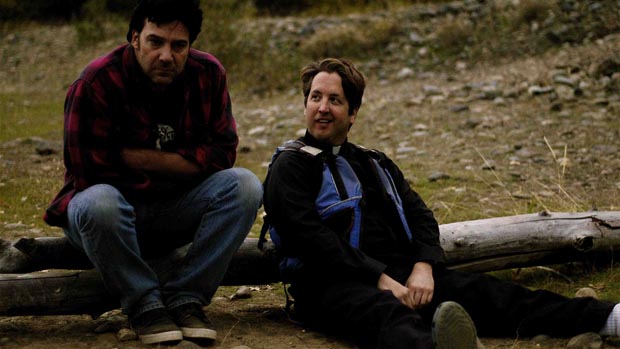

Enter Robbie (Robert Longstreet), a world-weary nowhere man in need of rescue from the animal shelter of life. Robbie’s baggy eyes and death metal T-shirt stand in perfect contrast to Billy’s doe face in a clerical collar. At an awkward first coffee date we learn that Robbie used to write fiction and this is why Billy idolizes him. “How many people write a novelette in high school,” exclaims Billy, much to Robbie’s horror that he even knew the thing existed. “My sister let me read it.”

Robbie is convinced to join Billy on a daylong canoe trip. They begin with a visit to the bathroom. In conjoined stalls resembling a confessional, after a few fart jokes, Billy’s face drops into profound sadness. He admits: “I’ve never been happy.”

And then he accidentally drops his Bible into a toilet full of diarrhea.

Billy panics. It’s funny-horrible. But the seriousness of his crisis finally seems to dawn on him: he can’t hide out in the trappings of religion anymore. All he has now is Robbie, the person who first inspired him.

It’s worth mentioning something about this word catechism. It refers to an education in the faith and usually comes in a question-and-answer format. The questions and answers, however, are predetermined and are usually memorized (think of the children at church in Diary of a Country Priest). It’s a method that has some merit and some serious limits. But catechism actually means to sound down, as in to sound down through the generations or to sound down into the ear.

As they float down the river, Robbie tells Billy stories. These stories definitely sound down. They appear on screen as micro-shorts — little vignettes with their own tone and inner life that are distinct from the film. They invite interpretation and questions. They are in every way different from the Internet urban legends that Billy is so comfortable with. In one, a highway worker named Miguel is trapped in a concrete pylon. The workers can’t get him out so they leave him there, making a small hole for him to breath and receive food. One day Maria comes along and, though she can’t see him or touch him, she falls in love with Miguel. She visits him every day and takes care of him.

Billy doesn’t get it. He complains that it has no ending, nothing happens, and it’s not about anything. Unlike the prescribed question and answer format of traditional catechisms, Robbie’s stories invite the listener to ask their own questions — the kinds that don’t have just one right answer.

“There is no punch line to these stories,” Rohal says. “The Mona Lisa isn’t about anything. Rubber Soul has no plot. The question you always get as a filmmaker is, ‘What is your film about?’ and that always throws me — I don’t know. I think the most exciting thing about filmmaking is figuring that out as you’re working.”

“Figuring it out as you go along” is pretty much the meat and potatoes of faith. But it’s not what Billy has been doing. Much like his stories, his faith is disengaged, predictable, and he’s forgotten his audience. Throughout the beginning of the film he hiccups out hosannas as if he were a choirboy with Tourette’s, as if there were no God who might answer this prayer (hosanna means “Save, I pray”).

There’s nothing especially scandalous about this behavior. Faithful people forget God all the time. The scandalous part is not anything that Billy does, but what happens to him. Which is, of course, the part that I don’t want to ruin for anyone who has not yet seen the film.

What I can say is that it is shockingly, horribly absurd. It’s the kind of thing that makes you cry, “Oh, my God!” out loud in the theater at least five or six times. But it is also the very thing that inspires Billy’s first true prayer of the film:

“Dear God…I don’t know why you’re screwing with me, but if you wanna be friends, please help me get back to church safe! I know you work in mysterious ways, so if your ways are going to get any more mysterious, please let that happen now. Thank you. Amen.”

To be confronted with the horrific and the absurd and trust that God is somehow in that too — that kind of faith is for mature audiences only. It is for the ones who understand Catechism’s last song, God Will Fuck You Up, from personal experience, which includes a good number of the saints in heaven.

In the end, it’s the kind of faith that you could only communicate with a story. If you tried to theologize about it, you would sound crazy.

Vocation, High Stakes and the Filmmaker

Todd Rohal had a back-up plan. “When I was a kid my mom had one talk with me about what I could do if being a director didn’t work out. It was either become a priest or a marine biologist — and I was terrible at science so that wasn’t happening.”

Rohal and I spent a lot of time talking about the similarities between priests and independent filmmakers. We all assume we’re going to live in poverty, but there is nothing quite like the feeling of knowing “this is it; this is what I’m supposed to do.”

Vocation is a term that doesn’t get much use beyond religious folks. Some people refer to it as a calling, which I don’t find at all helpful. What if you don’t hear a voice from on high? Is that what it means to be “called” as a priest? And what if you don’t fit your own image of what a filmmaker is supposed to look like? “I certainly don’t have the personality that I think a director should have,” Rohal says, “like Herzog…I’m not directing with a shotgun off-camera. I don’t like yelling at people. But does that mean this isn’t my calling?”

A better way to think about vocation is like this: It is the particular kind of work that best enables you to love your neighbor as yourself. The theologian Frederick Buechner once said, “The kind of work God usually calls you to is the kind of work (a) that you need most to do and (b) that the world most needs to have done…. [It] is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

This “deep gladness” results both from delight in the work itself and from the way this work draws you out of yourself. In that sense, it is a kind of salvation.

But where there is love, there is also sacrifice. Vocation will also drive you to your knees in prayer. This may not be a literal prayer on your knees. You may call all the creative passion, hoping, sweating and hustling involved in making a movie something else, but the old word for all that collective gut-wrenching is prayer.

The decision to make Catechism came about after Rohal’s initial attempt to make another feature, Scoutmasters, collapsed. During this time, Rohal was also diagnosed with a type of cancer. The way he put it to me was like this: “My cells since birth have been slightly defective, and I’ve just discovered this.”

Scoutmasters (now currently in post-production) was supposed to be the obligatory “next film” after his debut feature, The Gua temalan Handshake, with a bigger production and a bigger budget. When Rohal found out he was sick he began thinking about making Catechism instead. “…[M]aking another movie for no money just didn’t seem like the right answer, but it was…. It seemed like the healthiest thing to do was just go make something that felt like me.”

The script came quickly, inspired in part by summers Rohal spent doing maintenance and barcoding books at a Catholic seminary. “Some of the younger guys were incredibly funny, and we got along really well. Years later I found out that a number of them left the church completely, and it really made me think about the difficulty of making a decision like that — to be following the path of something you strongly believe in and then come to a point where you decide to abandon it.”

This theme of leaving or staying on the path you’ve chosen followed Rohal throughout his time making Catechism. In November 2010, while editing the film and just two months before it premiered at Sundance, he had major surgery. In the recovery room, “I was next to people who were like, ‘I was an investment banker for 30 years and then I got diagnosed with this cancer and I realized I need to pursue things that give me purpose — and that’s what you should be doing.’ And I’m like, ‘Buddy, that’s what I’m doing already, and now I’m broke and have no health insurance.’”

Rohal went on to suggest that Robbie was like the guy in the hospital bed, someone who could have achieved a lot more if he hadn’t listened to people telling him that he was never going to make enough money or affect very many people. These are the voices you can’t afford to listen to — the stakes of your life and your work are simply too high to listen to such nonsense.

“You’re going to affect somebody, somewhere. Maybe they’re going to find your movie in the back of a closet, and it’s just going to blow their mind. That’s the kind of thing that drives me. It’s just part of human nature to inspire people. And that connection, that spark, as hippie-ish as it sounds, that’s what this movie is about. It’s just one guy inspiring another guy who is completely unaware that this inspiration is taking place.”