Back to selection

Back to selection

Tribeca 2017: A Review of Tribeca Immersive

Alongside the Tribeca Film Festival’s film screenings and live events, the Tribeca Immersive exhibit at 50 Varick Street has been regularly packed full of attendees, with the enthusiasm of everyone from industry veterans to neophytes who have never seen a VR project before filling the space with energy. The event’s organizers, led by Ingrid Kopp, have done a stellar job in curating an excellent and diverse group of virtual reality and interactive projects from around the world, making Tribeca a leading global venue for new VR on par with Sundance or any other festival that includes virtual reality.

I was gratified to see several positive changes from previous years, foremost among them the convergence of Storyscapes and the Virtual Arcade, which previously were separate events but which now remain so in name only, a much more logical way to organize all of the festival’s VR pieces. Along with this is the fact that for the first time Tribeca Immersive runs the length of the entire festival rather than for just a few days. Long lines have been the bane of the event in years past and keeping it open longer has decreased this problem remarkably. It still exists, however: the space is open for individual sessions of roughly three hours each, and each exhibit is available for attendees to sign onto a waitlist as soon as the doors open. The result is that the lists for the longest (and most popular) projects literally fill up within two or three minutes, and all other visitors are out of luck. Capping lists at, say, five names at a time and making viewers wait to add themselves when a fifth slot opens up would alleviate this problem, and total list lengths could still be limited to the appropriate number of people per session. I visited the space four separate times, including on press day, and still wasn’t able to see some of the projects, like the NFB’s Draw Me Close, that I wanted to. But bottlenecking is always a problem for VR festivals and this arrangement is still better than the six-hour waits that greeted many attendees last year. Additionally, improvements were made in the quick response times by staff for technical problems and overheating headsets, the elimination of the ambient music that occasionally proved distracting last year, and even chilled drinks provided by Bai, a nice touch since neither drinking fountain on the floor works.

But all of this, of course, is in the service of the films, games, and artwork on display, and in this area Tribeca Immersive excels. One striking trend is the increasing length of the projects; quite a few this year are samples or trailers of longer pieces that are still in development, showing that VR is expanding in its narrative scope as well as its technical achievements. The pieces roughly divide into games, narrative fiction, documentaries, and what essentially amounts to visual artwork, although many of these blend together. What follows is my own opinion of the best pieces in each of these amorphous categories.

Games

Both Bebylon: Battle Royale and Life of Us emphasized the social aspect of VR gaming, with two players competing against each other in the former — a smash-’em-up arena featuring babies driving tanks, with seated players using hand controllers to guide the mayhem — and collaborating together in the latter. Life of Us would in fact work fine as a single-player experience, but the act of going through it with another person helps bring its chaotic joy to the surface. The piece, created by Chris Milk and Aaron Koblin, co-founders of the VR studio Within, is a cartoonish tour through human evolution, with players/viewers (I’m not sure which) swimming as a protozoa and tadpole, then emerging onto land to run from a T-Rex as some sort of basilisk, then moving on through being a pterosaur, an ape and a human to some sort of super-evolved alien-cyborg-ethereal-light creature. This of course culminates in a dance party with all the former creatures returning, and by that point, with any luck, the standing players have lost enough self-consciousness to really let loose, despite the fact that Life of Us consistently had the largest crowd of spectators in the entire gallery. One excellent touch is the use of microphones with voice modulating software that allows the two players to speak with each other; this involvement of the voice helps create a mutual viewing/playing experience and helps push the players into a more relaxed state. It was common throughout the Immersive space to hear Life of Us players screaming, yelling and laughing. The full version will be available soon.

Narrative Fiction

It’s nice to see a range of genres represented here, from children’s stories to outright horror. Both Sergeant James and Remember: Remember deal in the latter area: Sergeant James is an uncanny single-take live-action shot taken from under a child’s bed, while Remember: Remember is an animated alien invasion story (a segment of an incomplete work) told in room-scale VR. Much less assuming is Auto, a socially conscious story about an immigrant taxi driver who finds his job displaced by self-driving cars. Director Steven Schardt’s experience producing narrative films like Your Sister’s Sister allows him to confidently place the camera in positions that create a classical narrative film feel in a 360-degree space, but interestingly the most striking shot is an “overhead” angle on the driving car that shifts the viewer’s horizon 90 degrees; the effect, which lasts all too briefly, is that of flying laterally above the street.

But the most engaging adult-themed piece is undoubtedly Broken Night, which stars Emily Mortimer as a suburban wife dealing with both a fight with her husband and an intruder in their home. The film masterfully uses VR’s interactive capabilities — at certain junctures the viewer can turn their gaze from one scene to another to select which version will play — to create multiple possible narratives, something Scott Macaulay interviewed creator Alon Benari about earlier this week. Such a concept has been done before, but the technology has moved to a place where it is much smoother than previous interactive films, a feat aided by Broken Night‘s visual design. And the concept is more than a gimmick: this is the only narrative piece that I immediately wanted to watch again as soon I finished watching it the first time.

This year’s animated projects appropriate for adults and children include The Sword of Baahubali, Rainbow Crow, and Arden’s Wake — all three are samples of longer projects still in development. The Sword of Baahubali is a spin-off of the Indian film Baahubali 2: The Conclusion, a tentpole adventure film released in India this past week. While its action and animation are exciting — they might remind American viewers most of an Indiana Jones scenario — I found the frequent shifts in perspective, not least from first- to third-person and back again, distracting. Rainbow Crow, from Baobab Studios, moves completely in the opposite direction. Using room-scale VR and some of the richest cinema-worthy animation I’ve seen in virtual reality, it retells a Native American legend from various tribes about how the crow saved the Earth from eternal winter and lost his colorful feathers in the process. The portion shown at Tribeca isn’t enough to properly gauge the entire story, but the visuals alone are enough to make me excited to see it. (See my interview with producer Maureen Fan.) The same is true of Arden’s Wake from Penrose Studios. Like with their stellar Allumette from 2016, Arden’s Wake also features animation you can walk around but at a fraction of the scale of a life-sized piece like Rainbow Crow. Instead, the small characters are there in front of you at roughly eye level, and you can move around the space — in this case, in and out of a family’s domed metal house — with some of the most exquisite production design and character design in VR today. The story deals with a girl who lives in a deluged world after losing her mother at sea; when her father disappears under the water she must get into his homemade submarine and chase after him. That’s about all that’s contained in the current version, but, again, this is also one to watch out for. Praise should also go to the designers for their use of the vertical axis, one of VR’s most powerful tools that is too often forgotten, and smooth camera movements, particularly during Arden’s long descent down from her sea-top home. This is one to watch for.

Documentaries

Docs are slightly more common this year than fiction, and they too span a range of tones and material. The Possible: Hoverboards, from Jiro Dreams of Sushi director David Gelb, is a straightforward film, nearly a promotional piece, for some Canadian inventors who are developing, yes, a flying hoverboard. Similarly promotional is Ricardo Laganaro’s Step to the Line, a primarily observational doc about an adult education program run by Defy Ventures in a high security California prison. Most of the footage is of an event including inmates and outside volunteers as they tell each other their stories and recognize their shared human experience. The editing frequently swings perspective from one direction to another, which can make you lose focus, but the subject matter is very compelling and the moment when one of the inmates who has just shared his story of how his son died while he was incarcerated stares you in the eyes is both initially uncomfortable and ultimately quite touching, a very effective moment of putting the viewer in the place of a real participant and building a great deal of empathy for these men. His earlier statement, “I think empathy is better than pity,” sums up the entire project.

Several other projects — Neurospeculative Afrofeminism, Blackout, Becoming Homeless: A Human Experience, Testimony (about sexual assault), and even Tree — —all in one way or another share this interest in radical empathy and placing yourself in the position of someone different; in the latter case using VR to mimic being a tree itself. This isn’t the main goal of all these projects — Neurospeculative Afrofeminism for instance is also a trippy animation that explores the subconscious and features real-world items for sale — but it is a major theme running through the festival.

Beyond Tree, nature and conservation features heavily throughout the space as well. The most prominent of these is The Protectors: Walk in the Ranger’s Shoes, Kathryn Bigelow’s first virtual reality piece, which she co-directed with Imraan Ismail. Like the feature film The Last Animals, which also premiered at Tribeca, it features the brave park rangers at Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, men who put their lives on the line every day to protect their rapidly dwindling elephant population from a legion of terrorist-backed poachers. If it avoids examining the complex international issues that have led to the current crisis, it excels at creating a sense of space and immediacy as you move through the tall grass with the rangers or linger over a mangled carcass. Like last year’s The Ark, about Northern White rhinos, The Protectors makes the far-away problem of mass extinction present. But if it examines the horrors of man’s interaction with nature, Under a Cracked Sky, the New York Times‘ follow-up to last year’s excellent The Click Effect, shows the beauty of nature, the fun and nobility of scientific research, and the joy of discovering new life in one of Earth’s last frontiers. The piece follows a pair of researchers as they dive beneath the Antarctic sea ice, and the resulting footage is exquisite, making me think once again that VR is the future for much nature documentary.

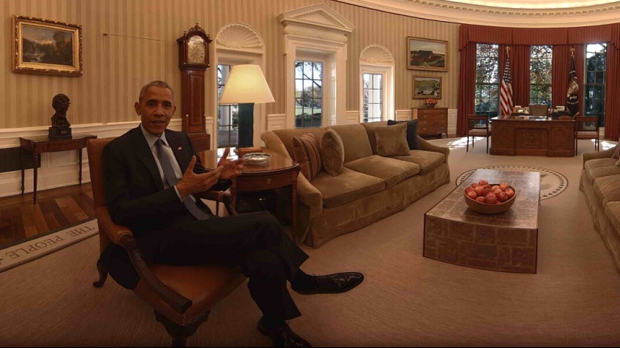

Some of the most moving projects are the most personal. Draw Me Close is an intimate piece from playwright/filmmaker Jordan Tannahill, about his mother’s terminal cancer, that, as mentioned, I was unable to see but which James Carter discusses in detail here. Most poignant for me was The Last Goodbye, in which Holocaust survivor Pinchas Gutter guides the viewer on a tour of the Majdanek Concentration Camp in Poland where he was interned and his family murdered. The room-scale live-action spaces are rendered in exquisite detail, making the viewer feel like they’re really there, and Gutter’s heart-rending narration makes this a harrowing — although also touchingly optimistic — film. (I interviewed creator Ari Palitz about the project here.) But perhaps the most surprisingly personal piece was also the most unassuming: The People’s House, a 22-minute tour through the largely empty rooms of the White House. It’s produced by the Montreal-based Paul Raphaël and Félix Lajeunesse of Felix & Paul Studios, who are perhaps best known for their Nomads series of short VR docs featuring indigenous people of Kenya, Borneo, and Mongolia. The concept is incredibly simple: Barack and Michelle Obama appear in a few shots and also narrate in voice over as the camera sits, largely static, in the Green Room, the Situation Room, the East Room, etc. The first time you find yourself seated close to President Obama in the Oval Office (pictured above) is the piece’s best use of the power of virtual reality; the sudden intimacy is surprising. But the key to the piece is the fact that it was shot the day after the last presidential election. There is a degree of weariness in both Obamas’ eyes, and when Michelle improvises about the inclusiveness and progress that she and her husband tried to make emblematic of the Obama administration the film becomes surprisingly emotional. The pain of the previous night’s setback is real and strong, but putting it in the context of the adversity faced by Presidents like Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis also embodies the optimism of the Obama administration, and cements their long view that progress will continue to bend forward towards justice, despite the fact that many of the pieces of artwork on the wall have already been removed. All of this makes The People’s House a pleasantly surprising project, and one of the best at the festival.

Visual Art

Speaking of surprises, the sheer number and variety of pieces that veer towards pure visual art was one pleasantly unexpected surprise. The Other Dakar from Senegalese artist Selly Raby Kane invokes a Matthew Barney carnivalesque atmosphere of lavish costumes and production design in a sparse narrative based on local mythology. Dutch artist Arjan van Meerten has created an elegiac apocalypse in Apex, an animated room-scale piece in which explosions, giant monsters and woody deer or elk skeletons walk the fiery streets to a pulsing musical soundtrack. Much more quiet is Hallelujah, a musical tribute to Leonard Cohen in which vocalist Bobby Halvorson sings a cappella four-part harmony with himself in a circle surrounding the viewer — the directional stereo in the piece’s audio is fantastic — before the final chorus bursts forth visually and aurally as he is transported to a Christian church and joined by a gospel choir. This piece represents one of the festival’s best uses of VR’s ability to manipulate sound and time.

Talking with Ghosts presents various short narratives that I’m including here due to their creation with Quill three-dimensional drawing technology. The pieces are essentially 360-degree comic books with a non-synchronous musical accompaniment that viewers click through at their desired rate, like reading a book; the one I saw, Sophia Foster-Dimino’s Fairground, depicts two friends saying goodbye at an abandoned fairground from their childhoods. Poignant and funny, it achieves a remarkable affect in a very short time and shows how comics can feature remarkably adult storylines and well-drawn female characters, even within tight narrative/time constraints.

Treehugger: Wawona was an equally beautiful but entirely different experience. Drawing on nature and biology — indeed, scientific data about the metabolism of giant sequoia trees — this can be considered another conservation-oriented piece (the California trees are increasingly in danger), but I’m including it here because of its sheer physical beauty. Viewers wear gloves and a vest as well as headsets to allow for you to manipulate points of light and color with your hands and feel rain falling on your body, and the space features a giant foam tree that you can touch and feel your way around; this corresponds with the image of a tree in your visor, and after a few minutes of exploring you are encouraged to stick your head inside a cut-out hold in the trunk in order to see what’s going on inside the giant plant. You then begin to move upwards, as though wafted off the ground by enormous invisible xylem, into the branches and tree top where you evaporate into thin air. The experience is visually rich with an overall feeling of peacefulness, but I was most impressed with the addition of aromas in a small addition to the visor near the viewer’s nose. Woody and wet, roughly a dozen scents cycle through the piece, but the technology is in place to add hundreds of others to different VR pieces in the near future, making this an exciting analog addition to enhance the latest digital technology.

Finally, speaking of analog art, one of my favorite pieces was The Island of the Colorblind by artist Sanne De Wilde. Using no technology beyond photographs, colored lights, and a pre-recorded narration, this low-tech addition to the Immersive space provided a richly interactive experience that delved both into ethnographic documentary and purely abstract visual art. Viewers were told about an actual island population that, through an accident of genetics, lost the ability to see color. While listening, red and green lights obscured the colors on the wall-sized photographs of the island, and viewers sat at a table and watercolor small paper print-outs of the same photos. All the paints look like shades of gray and black in the colored lights, and it was only when you emerge afterwards into the larger Immersive gallery that you could see what you actually painted. The experience of thus being temporarily colorblind was intriguing in and of itself, but De Wilde’s use of century-old technology to achieve was a welcome and forward-thinking change from the headsets at every other station.

**

Overall, if Tribeca Immersive is any true indication of the state of the art of virtual reality, I’d say the field is about to explode into much more relevance for all game designers, narrative filmmakers, documentarians and visual artists. Kopp and her team have once again shown that VR has a place alongside film, perhaps not just at festivals but in all our artistic practice.