Back to selection

Back to selection

“A Huge Historical Project”: Editor Kim Miille on Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities

Tell Them We Are Rising

Tell Them We Are Rising MacArthur Fellow Stanley Nelson has devoted his career to documentary explorations of the African American experience. The 65-year-old director/producer has made films on Marcus Garvey, the Freedom Riders and the Black Panthers. His most recent film is Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities, which premiered this week at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. Nelson hired editor Kim Miille to cut the film. Below, Miille shares her thoughts on historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), making archival photos and letters cinematic and her origins as an editor.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Miille: Both directors were familiar with my work and knew skillwise I was capable of taking on a huge historical project. What I find funny was the interview with the both of them, two powerhouse directors. I did my homework. I researched HBCUs. Came ready with ideas. It was Stanley’s decision ultimately who became editor. Somewhere during our conversation it changed from being an interview to I was working on the project. I actually stopped our conversation and ask, “Am I hired?”

Ultimately, I think, skills aside, it came down to personality and the ideas. I wasn’t afraid to be vocal and, maybe more importantly, I listened. When you begin the journey of editing a film you’re taking on not only the story, but you’re taking on the vision of the captain(s) who helms the ship.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

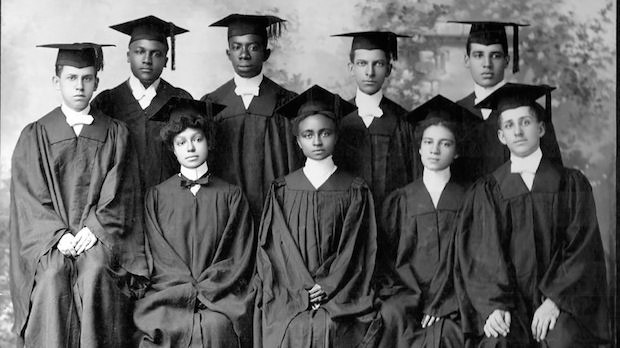

Miille: When I would tell my friends and family that the next film I would be working on was about HBCUs everyone would say, “Colleges and universities? How are y’all going to make that interesting?” The story of HBCUs is about the people within those campuses. How do you breathe life into these people’s stories? Their struggles? Their hopes and dreams? These stories shape our society today. That became my goal — to present and preserve these stories, their dignities in a meaningful, exciting and entertaining way.

African Americans overcame oppression and various daunting obstacles to gain an education. It was important to us to let them tell their stories in their own words. We used their letters, articles, interviews and footage throughout the film. We wanted to shine the light on their struggles, joys and achievements.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Miille: There is tremendous impact in how you direct the viewer’s attention inside a photograph, because a photograph can transmit the emotions of the people whose stories we’re conveying. We strove to let the photographs, especially when our only viewpoint of the past came from photographs, be a focal point of the storytelling.

We really had to focus on being simple and not getting in the way of the story. A way we achieved this was the use of recreations. I loved compositing the beginning hands. I wanted to convey the many voices behind those hands in their thirst for knowledge. Their defiance of oppression in the face of death. Their taking the reins of their lives in their own hands.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Miille: My editing career started in a swimming pool in midtown Manhattan. I love telling this story. I knew I wanted to get into editing. I wanted to become an editor. Documentary, narrative, it didn’t matter. It started with watching films with my Mom. We discussed and wondered about what made it and didn’t make it into the film.

When I moved into a new apartment, I received a “Welcome to the Neighborhood” gift of a three-month gym membership. The gym was equipped with a pool. I always wanted to learn to swim. So here I was, the first day I went to the gym, gasping for breath in the pool. Drinking probably most of it. An elderly man with a gravely voice encouraged me to “keep up the good work!” It was his first day in the pool as well. It turned out he was a documentary editor and he worked across the street from the gym. That’s how I met Victor Kanefsky, and that’s how I became a “Valkynite.”

I was able to work with Victor, and later Sam Pollard, Spike Lee, Barry “Cutmaster” Brown, and St. Claire Bourne. I couldn’t ask for a better foundation. They each brought their own style and strengths that helped mold and shape me to who I am today. I look up to each of them.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Miille: I am currently working on Avid Media Composer, and that’s my preferred NLE. I recently edited a feature short by Pete Chatmon, Black Card with Adobe Premiere. I also have worked with FCP X and 7. I feel it’s not the gear or the system that make the edit. It’s the skill and the heart behind the hands.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Miille: The opening of the film was tough. The villainy of slavery can overtake you. How much do you tell? What does the viewer know? However, when we focused on the agency of the enslaved people, the first act took shape. It’s through their eyes and struggles that lead us to the foundation of an HBCU.

Filmmaker: What role did VFX work, or compositing, or other post-production techniques play in terms of the final edit?

Miille: A tremendous amount of history came to us in written form. We really wanted these words to come alive. We’ve all seen words on a screen before. How text comes on the screen — sharp, smooth, suddenly — affects the viewer’s emotions. The question is, what do you want them to feel? Sometimes the emotional is more important than the intellectual.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Miille: I watch the end of the film and get such a charge. I can’t wait for the kids, their parents, their friends to see themselves in the footage. Can’t wait for the alumni to hear their stories ringing out from the past. It’s also nice to know that it could influence others to see their future on a HBCU campus.

I knew (or thought I knew) the story of Brown vs. Board of Education. It’s taught in school after all. After working on this film, I know that I didn’t get the complete story. I felt this way several time in the making of this film. I can only encourage people to watch out for more stories on the website. What didn’t make the film will eventually be made known there.