Back to selection

Back to selection

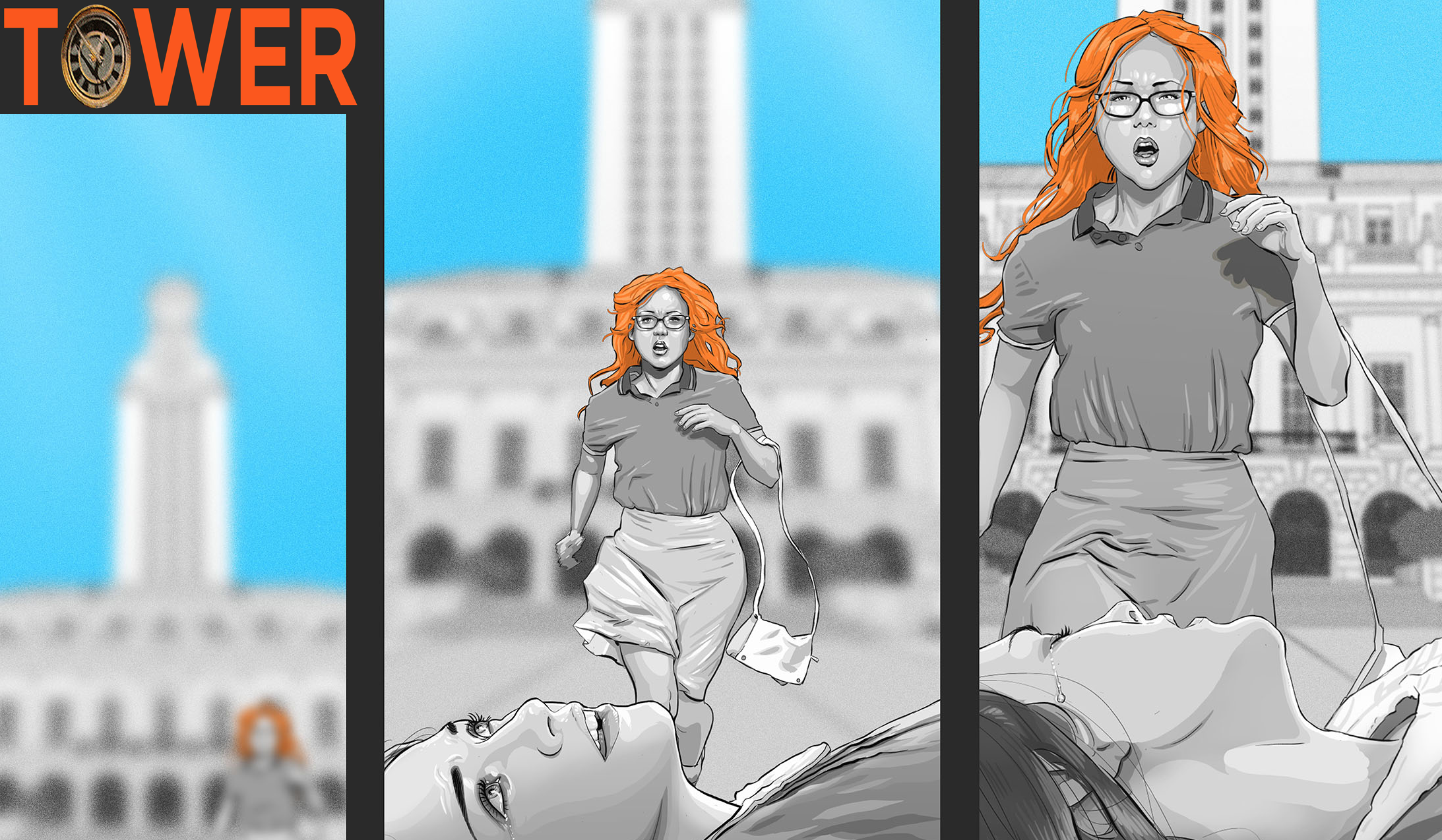

Using Interviews and Animation to Bring the Sniper Documentary Tower to Life

The documentary Tower recounts the day in 1966 that a sniper on the University of Texas Tower killed 14 people and wounded dozens more. The film includes archival footage, interviews with those who were present and animated recreations of the event.

In this interview, director/producer Keith Maitland and DP Sarah Wilson talk about the making of the film which receives its broadcast premiere on PBS on Tuesday, February 14th.

Filmmaker: How did you become filmmakers?

Maitland: I started off in narrative filmmaking, working on other people’s movies, and right around the time I met Sarah — we’ve been together 13 years — I really wanted to be directing projects of my own. When I saw Sarah’s incredible documentary photography, and the way that people responded to the stories that she was telling, it made me want to become a documentary filmmaker and impact people emotionally through telling a story.

Wilson: As a documentary photographer I concentrate mostly on taking portraits of individuals within a community to tell the story of the community. When Keith and I met I was working on a project about Jasper, Texas and a hate crime murder that had happened in 1998 where three young white men dragged an African-American man behind a pickup truck.

Filmmaker: How did you come to make Tower?

Maitland: Having grown up in Texas I’d heard bits and pieces of the story through the years. I attended the University of Texas in the 1990s and expected to learn about the story on day one. But they didn’t really acknowledge its existence.

Ten years ago Texas Monthly magazine published an oral history of that day, and it was while I was reading that story that the idea to make the film was born. I knew almost immediately that I wanted it to be animated and that I wanted to create a visceral experience for audiences that would transport them right into that moment and force them to live through this horrific, long and hot experience that the characters of the story lived through.

At the time I was in the midst of making my first documentary feature, so I spent six years thinking about making Tower, talking myself into and out of it. And Sarah was always the person that I talked to about it. We started making Tower in 2012 with the idea of releasing it for the 50th anniversary.

Filmmaker: What made you decide to animate it?

Maitland: The stories that the people tell are just so seated within the geography of the campus. When someone says, “I started in the Student Union, I ran across the West Mall, I went behind the English building and poked my head out, there was a good view of the Tower from there,” having gone to the university I knew exactly what they were talking about.

I’m a visual person — I just started matching the visuals, and it was visceral, and it was intense, and I felt really drawn into the story. I knew that the film would be mostly a recreation of that, but I also knew that the University would never allow us to film a recreation on campus.

Even though we shot actors with props, and painted on top of the footage, I knew that there was an opportunity to swap out the backgrounds and recreate the campus for the animation. I really enjoyed being that creative and working with that much planning and manipulation of all the details.

Wilson: We filmed much of it in our back yard. Keith had to think in several different dimensions and really use his imagination at the time of filming because so much more was going to be added later through animation.

Filmmaker: What was the process? Did you write a script or storyboard?

Maitland: We did initial interviews of about 20 people, and then narrowed that down to eight. Then I took those transcripts and using Final Draft wrote a screenplay. Every detail and word spoken in the screenplay was taken 100% from those interviews.

Once I felt satisfied that we had a good script, I cast actors who resembled these people, as they looked in 1966, but also who could perform the interviews in a compelling way that aligned with the personalities of the real people. It’s one of the things that make this a little different; by having the actors perform the interviews we get to transcend time. It’s not a movie about people reflecting on what happened in the past, it’s a movie about people experiencing a present tense set of emotions.

But I also knew at some point we would cut from the actors to the real folk and so the performance and the casting of the actors was key so that the transition would not be jarring.

Filmmaker: How long did it take to shoot?

Maitland: If we’d had all the money up front we would have done it over the course of 15 days or so, but because we were an independent operation, we filmed the scenes spread out over the course of a little over a year, in two or three-day increments.

Many of the scenes were shot in our backyard; some were shot in parking lots or a local park. We even stole a few locations like a stairway and the elevator scene at some local warehouse spaces that matched the dimensions of the Tower’s elevator and stairway.

Then we edited that material and handed off those edited shots to our animation team and they began animating at 12 frames per second, and that’s a really painstaking process. Every night at about 10:00 PM there would be anywhere between five and 15 seconds of animation in my Dropbox, and it was always the highlight of my day. But it was a slow and daunting process.

Filmmaker: How long did the animation take?

Maitland: We had a total of 18 animators working for about 18 months. Because we were shooting the production in bits and pieces, as soon as we would shoot something we would then start animating it. This meant that we were animating pieces for a film that hadn’t actually been assembled in full, which is a little scary because the animation process was so expensive and so time consuming. The last thing you want to do is animate pieces that end up on the cutting room floor.

We were really careful about our process so that we were only animating things that we were absolutely sure were going to be in the film. I’m proud to say that there’s only about 15 seconds of animated footage that didn’t make the film.

Filmmaker: How much archival footage did you have?

Maitland: There were about 14 minutes of archival footage from the day, from three newsreel photographers on campus, running around with 16mm cameras. Most of that footage was available online, and I’d seen it during my research phase.

It’s part of what made the animation make sense to me because that footage looked like cinematic wide shots, and the footage sets the tone, the tension, and feeling from that day. As we were planning the animations, we worked with the archival footage. Even when I was scripting, we would use pieces of archival footage.

My editor Austin Reedy, coordinating producer Hillary Pierce and the whole team were always looking for more archival footage, including material that wasn’t necessarily from that incident but was reflective of Austin at that time. When we show the police officer driving to campus there are these great driving shots through Austin. Those weren’t taken on August 1st, 1966, I think they were from a year earlier, but they were a great glimpse of what Austin looked like at that time.

Filmmaker: Why did you do the animation in black and white?

Maitland: Because the archival footage is black and white. I knew from the beginning that the film needed to have a black-and-white palette throughout. Because we were using archival footage and animation co-mingled, I didn’t want it to feel jarring.

At the same time, it’s a lot of time spent in a drab palette, so we looked for opportunities to introduce color wherever we could. We came up a grammar that when we introduced the characters we would introduce them in color and they remain in color until the moment when they realize what’s happened, and then they would desaturate and become black and white. But if there were ever flashbacks to moments in their lives before the shooting, that was an opportunity to use color again.

Filmmaker: How did you film the recreation footage you used as the basis for the animation?

Maitland: We filmed much of the action in the backyard. We have a 40-foot tall palm tree in the corner of our yard that stood in for the Tower for eye line for the actors.

It was often a two-camera setup, and I would describe to the actors and Sarah where they were standing on campus, where the Tower was, and where the other characters that they were looking at were to give them reference. It was rare, but I would occasionally pull out a tape measure and mark some dimensions for the actors to work within.

After we’d edited the scene we’d go to the campus and usually with my iPhone take background video of the locations, matching the angles we’d shot in our backyard so that the animators had a reference to create the backgrounds. For these reference shots it didn’t matter the depth of field, or the lens quality.

Filmmaker: How were the interviews shot?

Wilson: We shot with two cameras, either in a studio, or we did some of the interviews in our living room, with a white backdrop, lighting, and two Canon C100 cameras.

Maitland: I defer completely to Sarah because lighting is not my forte and as a photographer she understands light and those kinds of setups so much better than I do. And I’m also directing, which allows me to stay focused on the relationship between the subject and myself.

Filmmaker: Were the recreations shot with the C100 as well?

Maitland: Yes. Everything but the backgrounds were shot on them. We bought a pair of them when we got started; I love those cameras. They’re the perfect size for a run-and-gun documentary filmmaker to just grab out of the bag and be ready to go without a lot of fiddling with them, but they’re also as customizable as some of the bigger cameras.

Wilson: And I had a bunch of really nice lenses because I had been shooting with the Canon 5D Mark II and III, and so it was nice to be able to use those lenses for video.

Filmmaker: What lenses were you using?

Wilson: We mainly used an 85mm f1.2, and a 70-200mm f2.8. Sometimes we’d use my 50 f1.4, wishing I had a f1.2, but it was a mixture of those. Every once and a while we’d go wide, but mostly for interviews it was the 85mm and the 70-200mm.

Maitland: I really like the way a long lens works in an interview setting. It gives the audience a very intimate shot, but it allows a little space around the subject so they don’t feel closed in.

I manned the A camera, which is shooting directly at the subject at their eye line, and I’d stand directly behind the camera and conduct the interview just peaking over the top of the camera. I didn’t touch the camera, it was a locked off shot.

Sarah manned the second camera, which is the more active camera with a 70-200mm because it allowed her to play and move without swapping glass in the middle of the interview and she had the freedom to reframe and to change focal length.

Filmmaker: What was the most unexpected problem that you had?

Maitland: The most unexpected problem was choosing whose stories to leave out. It’s so difficult to reach out to people and ask them to access these horribly traumatic memories and then realize that you’re going to have to leave some of those stories out to make the film compelling. It was something that I struggled with. and it’s why I’ve continued to collect stories of people that were there, though not the high-quality interviews that we did to make the film. A lot of them are recorded telephone interviews, but we made a goal to hear the stories of the people that were there and to offer them an opportunity to tell their story and whatever cathartic positivity that could be born of that. The door is still open; we continue to collect stories of people that were on campus that day.