Back to selection

Back to selection

What Can Happen in the Frame: Sasha Waters Freyer on Her Doc, Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable

Photography was all over the New York City art world of the late 1980s. There was the Pictures Generation—artists like Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger and Laurie Simmons, who began in the mid ’70s and whose conceptual use of appropriated or staged photographs cast a critical and sometimes seductive eye at the way mass media imagery shaped consciousness. Jeff Wall, Philip-Lorca diCorcia and, later, Gregory Crewdson were bringing the staging techniques of film and theater to photographs charged with emotional and narrative possibility. And the work of photographers of an earlier generation, like Diane Arbus and Robert Frank, was still highly influential, with Arbus’s focus on outsiders connecting with the era’s performance art while Frank’s body of work, which crossed cinema and photography, influenced filmmakers such as Jim Jarmusch and Rick Linklater.

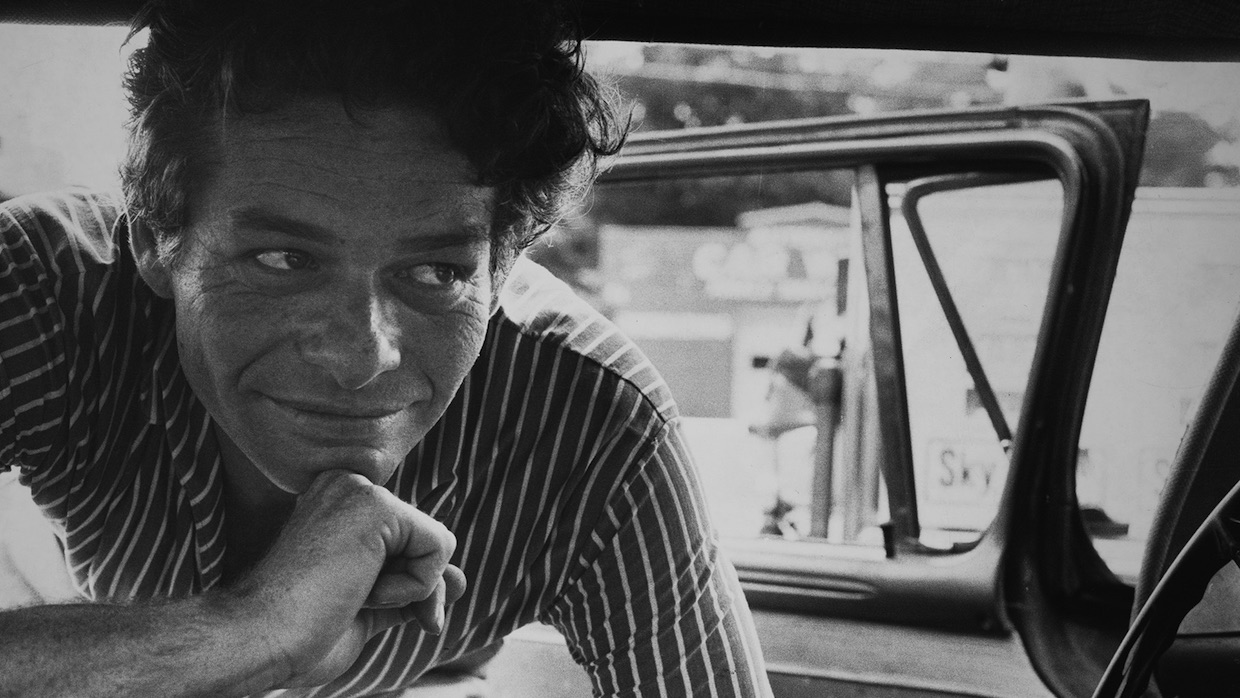

And then there was Garry Winogrand. Born in 1928, Winogrand began his career as a photojournalist and commercial photographer before, in 1964, receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship for “photographic studies of American life.” His street photography was included by curator John Szarkowski in an influential 1967 MoMA exhibition alongside Arbus and Lee Friedlander, and he went on to publish several books, including a curious one that detailed the interactions between humans and animals at the zoo (The Animals) and another, Women Are Beautiful, a somewhat obsessional series of photographs of mostly young women captured in public moments of reverie or introspection, that was dubbed by both critics and admirers as sexist, misogynistic, or, simply, “problematic.”

Winogrand died of cancer in 1984, the year I graduated college and went to work in the New York art world, and I’ll admit to knowing far less about him than the other artists just named, who seemed to more obviously engage with the intellectual issues of the day. Interviewed in Sasha Waters Freyer’s riveting, deeply insightful and altogether consummate documentary Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable, photographer, writer and curator Leo Rubinfien puts Winogrand’s reputation at the time in context, referencing the drift toward irony in much ’80s art. Dubbing Winogrand an “anti-Warhol,” he says, “As the national culture moved in the direction that it’s all illusion, that every face is really a mask, that every statement is really a joke, I think that possibly Winogrand would have seemed less relevant.” Or, as fellow interviewee Tod Papageorge says, “Deconstruction, the love of Barthes and Foucault, and all the rest of it, it became a miasma for photography, and Garry went down with the tide.” (This is even as Winogrand’s own statements on photography—“I photograph to find out what a thing looks like photographed”; “Photos have no narrative content; they only describe light on a surface”—crackle with a kind of postmodern wit.)

Four years after Winogrand’s death, the substance of this very dialogue became the lede of the New York Times review of his mammoth self-titled exhibition, organized by Szarkowski at MoMA. Wrote critic Andy Grunberg, “It would be no great exaggeration to say that over the last 10 years, the art of photography has split into two irreconcilable camps. On one side are the postmodernists and their allies, who see photography as a particularly useful and provocative means of making images that address the issues of art in our times. On the other side are those who hold to the more traditional view that photographs are connected not merely to the world of art, but to life itself. This latter group, which has been on the defensive through most of the 1980s, will find a measure of solace in the Museum of Modern Art’s retrospective exhibition of the work of Garry Winogrand….”

It was at that 1988 show that I, enamored of everything postmodern, first encountered Winogrand, and the exhilarating sensation of seeing his work, that onrush of images, was the first thing that came flooding back to me upon watching Waters Freyer’s film. Whatever my allegiance to the Pictures Generation, with that MoMA show, I became a Winogrand fan. Shooting often with a Leica M4 and a 28mm lens, never invisible, getting close to his subjects, Winogrand was a photographic machine. (“Being married to Garry was like being married to a lens,” said first wife Adrienne Lubeau.) His spontaneous, wide-angle compositions would cantilever the horizon line, producing tilted frames packed with potential points of interest—a pictorial turbulence that mirrored America’s social change in the ’60s and ’70s. He was a master photographer of crowds—women rushing on sidewalks, student protestors at demonstrations, masses of people waiting in airport lounges—while some of his best photographs captured an essential loneliness of modern life.

When Winogrand died, he left behind 4,000 rolls of developed but not printed film and 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film. He had moved from New York to California by this time and was experimenting with different ways of taking photographs, including from the windows of moving vehicles. Szarkowski’s show was the first to feature some of these posthumous images even as the curator used them to advance a critique of Winogrand’s late work that functioned also as a kind of biographical end point. Compulsively shooting, never stopping to develop, edit, and print, Winogrand, argued Szarkowski, had descended into a mechanical ritual of undisciplined image taking. Describing much of this work as “deeply flawed” and “pointless,” he wrote in the exhibition catalog, “Many of the last frames seem to have cut themselves free of the familiar claims of art. Perhaps he had lost his way….”

The debate over Winogrand’s late work was rekindled in 2013, when curators Rubinfien and Erin O’Toole mounted another major retrospective at SFMOMA, this time featuring nearly one-third new images printed from the contact sheets for the first time, with the later work containing a spare poetry and, in some cases, terminal bleakness—one now-famous shot, snapped from a speeding car, features a woman lying in the gutter outside a Denny’s in the full light of day—that feels as emblematic of the late ’70s into the Reagan years as his earlier work captured Viet Nam–era social change. By the time of this retrospective, Winogrand’s thousands of unviewed shots suddenly didn’t seem so strange—after all, we all have cameras in our smartphones, cloud storage plans, and plenty of our own photographic detritus we’ll never bother to look at, either.

To continue the conversation, now, there’s Waters Freyer’s sleek film, which elegantly strides through Winogrand’s career, allowing the photographs to tumble from one to the next, full frame, as a raft of erudite photographers, critics, and artists (including Pictures Generation star Laurie Simmons, who confesses to once hating but now loving Winogrand’s work) tell his story. With a killer soundtrack and apt literary intertitles (quotations from John Updike and Don DeLillo, among others), it’s an astonishingly assured film from the Virginia-based Waters Freyer, whose previous filmography throughout the 2000s spans from films on art and theater (This American Gothic, Chekhov for Children) to more experimental short docs, such as 2012’s Our Summer Made Her Light Escape (the latter she describes as “a wordless portrait of interiority, maternal ambivalence, and the passage of time.”) Deeply pleasurable for the Winogrand fan, and an ideal gateway work for the newcomer, Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable is organized around a particular insight, a combination of analysis and scholarship that I won’t reveal here. Waters Freyer and I discuss it below, however, and suffice it to say that her deeply moving, ultimately redemptive take on Winogrand’s later life and work just may be this subject’s satisfying last word.

Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable is in theaters this fall before airing on American Masters nationwide.

Filmmaker: Depending on the day I’m asked, and on most days, I would say Garry Winogrand is my favorite photographer. But it wasn’t until I watched your film that I placed how, when and in what context that affection developed. So, I’m curious what this process of rediscovering Winogrand was for you, and how your thoughts on Winogrand were affected by making the film.

Waters Freyer: I studied photography—I graduated from SVA [School of Visual Arts] with a BFA in photography in ’91, and the MoMA retrospective happened [in 1988]. I always loved Garry Winogrand and his work. I had all his books, and I spent a really long time at that MoMA show, and then, like everyone else, kind of forgot about him, really, until the 2013 retrospective that opened at SFMOMA. I thought, oh right, Garry Winogrand—that guy’s work is amazing! And then I thought, well, is it really amazing or just one of those things I loved in college? I went back and looked at the work again and thought, this work is great. And going back and spending time with the work and then also talking to all of these wonderful people about him really helped me to think about why the work is so great, and how I could sort of defend liking it even though there are things about it that are problematic.

Filmmaker: Was part of the challenge of making the film, then, overcoming a resistance to those things that are problematic? Or understanding those things in a new or different way?

Waters Freyer: Well, I definitely went in knowing I didn’t want to do some sort of hagiography. I’m not really that interested in that kind of filmmaking. Erin O’Toole at SFMOMA, who was one of the curators [of that retrospective] with Leo Rubinfien, was one of the final people I interviewed, and what she said resonated with me. She talks about Women are Beautiful as being bad because it’s just not really a well put together book. It’s what he’s best known for, but it doesn’t reflect his work very well. She told me that when she was first asked to work on the show, she thought, “I don’t know,” because he does kind of come with this baggage. But that baggage is interesting to me in terms of thinking about biography and the relationship between the work and the person. Winogrand would never talk about photography in terms of content, right? It was always about solving a formal problem. But so much of the content of his work reflects his own interests and obsessions.

Filmmaker: Talk more about the baggage—in what way was it interesting to you as a documentary filmmaker?

Waters Freyer: I wasn’t thinking about this going in to the movie, but, once I had the interview with [photographer and critic] Tom [Roma] and then the things that other people said about Garry and his family, his children, and then when you look start looking at The Animals—that’s a body of work that he makes basically because he’s at the zoo with his kids on the weekends. That divorced dad thing. I really wanted to take aim at that trope in biographies of male artists, like “the bad dad,” “the bad husband,” which is right beside this cliché of, “Well, it’s OK he was this kind-of jerk, but we have the work and so it doesn’t matter.” He really struggled with wanting to be closer to his family, with not wanting to get divorced, and you see the struggle in the work. It’s a question that is not often asked of male artists: what about that conflict between making work and being a parent? That’s something I think about a lot. A lot of my own short work is about motherhood from the perspective of being a parent, but in a very sort-of elliptical, experimental way.

Filmmaker: What about the photographs themselves—how do you connect to the work on a more personal or emotional level? I’m a child of the ’60s, and there’s a strong sense of nostalgia for me in his photos.

Waters Freyer: I grew up in New York City, so there’s a little bit of nostalgia for me, too. I’m also really interested in the thing that he does formally with trying to put as much in the frame as you can before it just totally falls apart. It’s an interesting formal challenge in filmmaking, too—how much can you keep throwing into a film before it falls apart?

Filmmaker: So not having made a film like this before, how did you convince what I presume was a tough estate that you were the right person to tell Winogrand’s story?

Waters Freyer: I got incredibly lucky. It was in 2013 when I started looking at this work again, and I thought, this work is so great and so complicated, and he is so interesting—why isn’t there a film about him? And then I called the Fraenkel Gallery because they represent the estate for Garry’s widow, and I just asked them. They said, “Oh, no one’s ever asked.” Really? Often [when there hasn’t been a film], there’s a problem with the estate, which is why there is no Diane Arbus documentary. Or, there are five people all trying to make one. They said, “Why don’t you write a proposal, and we’ll think about it?”

And, so that’s what I did. I did additional research, talked about who I’d want to interview, and the estate said OK. For three years, I just had this very informal e-mail agreement with them. When [sales agent] Submarine got involved, they said, “We want to see your contract with the estate.” And so I just forwarded them all these e-mails, and they were like, “No, no, no, you actually need something a little more than this.” By that point I had been shooting a lot, and they had looked at a rough cut, and I had gone out there and met with Eileen [Hale Winogrand] and Jeffrey Fraenkel, interviewing both of them for the film. They were like, “OK, let’s do it.” The one restriction was that I had to show every photograph full frame. There are a few times I’ll start close and cut out to full frame, but for the most part it’s a lot of very still static images. I actually really appreciated having that as a restriction because I think it gives [the film] this formal quality that really reflects his work. I don’t think I would’ve done a lot of pan and scan anyway, but it was sort of nice to have that built into the agreement.

Filmmaker: That’s one of the things I loved about the film—the luxuriousness of being able to just look at a photograph. It’s interesting, too, because Winogrand is known as this photographer of motion—people rushing on streets and sidewalks—and I suppose the lazy filmmaker analog of that would be lots of pan and scan and zooms. But at the same time, yours is a propulsive film because of the way it’s cut, the images one after another. It feels fast even if the images themselves aren’t moving.

Waters Freyer: Early on, I had this structure where it slowed down. In the beginning, I hold on photos for four to five seconds and by the end I was holding on photos for a really long time. But it felt like one of those almost structural ideas, and it ultimately didn’t work. But I do try to hold on things. It can feel a little overwhelming when you see it projected—to see those images that big. There are some images that you feel like you could look at them longer because there’s a lot happening in the frame.

Filmmaker: You build to this almost like Rosebud moment, which I won’t spoil. But it’s interesting to have a biographical film about a somewhat well known person that contains a spoiler.

Waters Freyer: It happens really late in the film. In real three-act structure it would come 10 minutes earlier, but there was just no way to get it in earlier.

Filmmaker: The moment we’re talking about is a combination of discovery and analysis in which you’re challenging crucial aspects of the narrative Szarkowski wrote about what Winogrand was doing at the end of his life.

Waters Freyer: By the end of the film, I want viewers to come away with a realization that there is no definitive view on the late work. Szarkowski made these claims, but a lot of other people disagree. And when you go back and look at that work again, there’s a lot more there that he didn’t see. I don’t think there’s any one person who has seen all of the contact sheets. But there are actually a couple of ways in which the narrative of the film challenges Szarkowski. Pretty late in the editing process, a really old friend of mine who’s a photographer watched a cut, and he said to me, “I don’t feel like the picture edit is enough your own.” Like, it was still too reliant on John Szarkowski and Leo Rubinfien. It wasn’t until then that I realized I needed to stop deferring on the selection of images and the sequencing. That’s when I went back and added more discoveries from the contact sheets. I felt more empowered—like, “I’m picking a picture that I think is a good Winogrand even if Szarkowski and Rubinfien didn’t pick that one.”

I went out to the Center of Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, where all the contacts sheets are scanned and digitized, for a week pretty early on in the process. My friend Jeff Lad, who was the picture edit consultant, picked some of the photographs as well. [We were] going through and looking for the shoes at the end and the shadows— that was what Tom was talking about [when he described that] sort of Rosebud moment. And finding those in the contact sheets took a while.

Filmmaker: Wow, so you constructed that moment from the Tom Roma interview. And once you had the quote, you went back and found the work to support it. You can only really do that, I suppose, with an artist who left so much work that hasn’t been pored over.

Waters Freyer: Tom’s interview was shot really early on. I shot six interviews in three days, and it was on that third day that he told that story. You could hear a pin drop in the room—we were all so moved. So, I knew early on that I would organize a lot of elements of the film around that story and that I’d go back and find its visual documentation.

Filmmaker: What about the decision to hone in on specific photos from Winogrand’s vast corpus? Some photos get much more explication, like the interracial couple with the chimpanzee.

Waters Freyer: I told most if not all the people I was interviewing that I wanted them to talk about a particular picture. And so Leo discusses the one of the three women walking down the boulevard, but he also talks about the picture with the chimpanzee at length. But if other people hadn’t brought it up, I would have had to address that particular picture [myself] because it is very controversial. The African American artist Carrie Mae Weems has appropriated that particular picture for her own critique, and I thought about interviewing her. But then once I had this back and forth between Leo and Jeff Scales, I though, well, if I interviewed Carrie that’s even more time on that picture, and I don’t think it deserves that much more attention. But it is important to address.

Filmmaker: When did American Masters get on board, and did their involvement shape the film in any way?

Waters Freyer: You know how it is with these documentaries—they take five years. I first met with [American Masters’] Michael Cantor because we know each other through the New York documentary world. He’s actually the person who introduced me to David Koh at Submarine. He was relatively new to American Masters, and I think he was quite anxious to make [the series] his own—a little younger and more diverse. And he was understandably quite hesitant—like, you know, Garry Winogrand is great, and an American master, but he’s a dead white guy. He said to stay in touch and send updates. Then Submarine got involved, and I had this successful Kickstarter campaign, and they saw that there was going to be interest and support—this wasn’t just some straight photography [story] from the ’70s that no one cares about. There’s this younger community of people who are into [street photography], and this will bring in that younger audience as well.

But in terms of the editorial input so far, they’ve had none. I mean, I’ll have to make the film nine minutes shorter for PBS, and deal with the nudity and cursing and all of that. I would say the person who had the most editorial input was David Koh from Submarine—he is one of the most brilliant people in documentary I’ve ever met. He was just so smart, so supportive, and kept pushing me in a particular way that was just amazing. He probably made me cut and recut the opening of the film 25 times. I could not get the opening right. It would be so close, but not working, and he’d say, “You’ve got to go again.” I was like, “I can’t. I don’t know what you’re trying to get me to do.” Then, finally, one day, I went back to this mountain of transcripts and found that thing that Garry says about wanting to disappear, to be invisible. That’s crucial, but I didn’t have it in the film until late October, and I locked in November. That opening was probably the last thing I cut.

Filmmaker: So, a thematic statement up front.

Waters Freyer: A thematic statement that also connects to the end of the film. There is this moment at the end of the film where he talks about how people say his images are about motion, but they’re actually about stillness. And, then, he did disappear from the art world canon, probably in a way that he wouldn’t have wanted to do. And now he’s back.