Back to selection

Back to selection

“A Railway Police Officer Came to Question Her”: Directors Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang | One Child Nation

One Child Nation

One Child Nation Whenever directors watch their own films, they always do so with the knowledge that there are moments that occurred during their production — whether that’s in the financing and development or shooting or post — that required incredible ingenuity, skill, planning or just plain luck, but whose difficulty is invisible to most spectators. These are the moments directors are often the most proud of, and that pride comes with the knowledge that no one on the outside could ever properly appreciate what went into them.

So, we ask: “What hidden part of your film are you most privately proud of and why?”

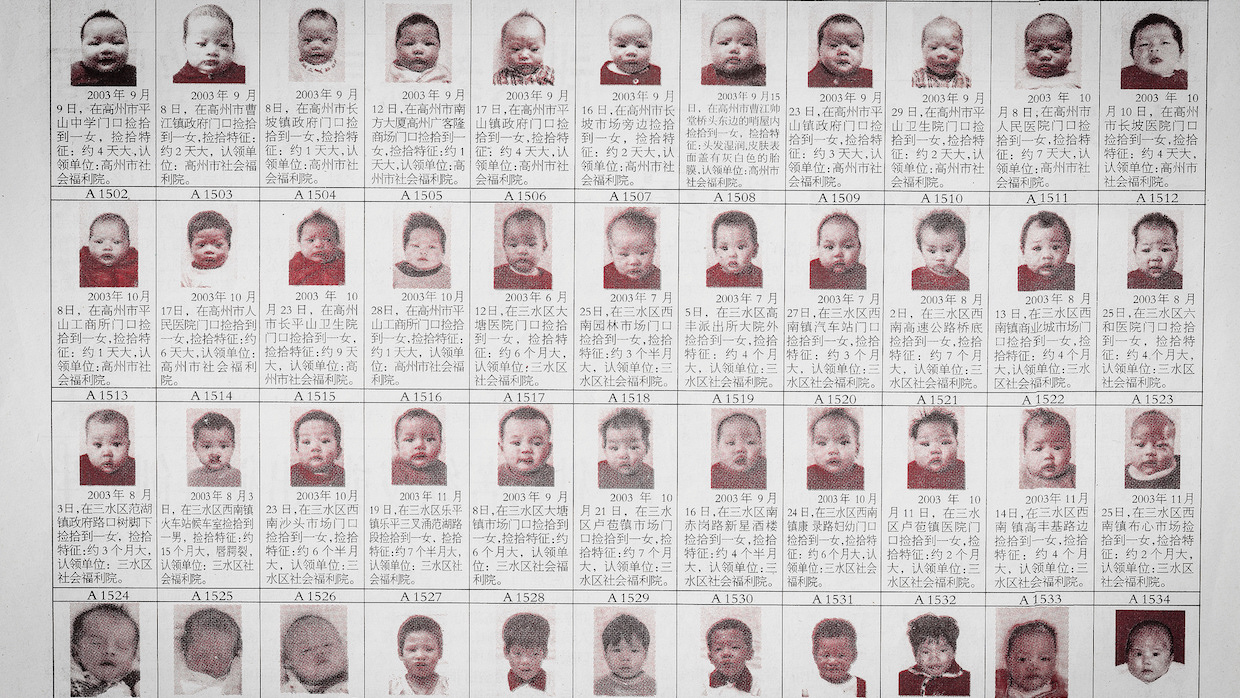

From very early on, the question of how to visually show the One Child Policy was always on our minds. When we went to speak with our characters, we were of course interested in their stories, but we were pleasantly surprised that many of them also had saved photos, newspaper clippings, or other objects that visualized the policy in some way. For example, someone we filmed but who wasn’t included in the film has two rooms full of One Child Policy propaganda material, and his hope is that one day he can open a One Child Policy museum; another character in our film has probably the largest existing collection of newspapers printed with information about children in orphanages awaiting adoption. As a filmmaker, I felt very lucky to have access to those compelling visual elements. — Nanfu Wang, co-director, producer, cinematographer, editor

Whenever Nanfu travelled to China for shoots, I used a GPS tracking app to see her location in real-time. We stayed in touch multiple times a day and made emergency plans in case we lost contact with each other. We avoided using China-based social media apps or email platforms. We reduced the local crew to the smallest possible number to avoid unwanted attention. It’s uncertain to what extent Nanfu was being monitored by the government due to her previous film, Hooligan Sparrow.

During her trip to China to film ex-human trafficker Duan Yueneng, she needed to get on a train with him to film his previous baby-transporting route. In China, buying a train ticket requires a state-issued ID card. Not long after she boarded the train, a railway police officer came to question her. After a few questions, he left for a moment, but he came back and sat right next to her. She couldn’t film and wasn’t sure if more officers would come take her away. When the train arrived at the next station, Nanfu hurried to the door and jumped off the train. It was midnight at a remote train station in the middle of nowhere. She jumped on the first motorcycle taxi she could find but wasn’t sure if she was followed. I was in Massachusetts, and during this whole process I tried to help coordinate her “escape” by suggesting safe locations and trying to reach local drivers. One lucky thing was that we had expected that situation and had arranged for a driver to drive along the railway, ready to pick her up any time. After about half an hour on the motorcycle, running from place to place, Nanfu finally found a hotel where she could use the lobby to wait for the driver. During her wait, we discussed hiding footage in the bathroom. Luckily, the driver arrived quickly.

We still don’t know why that police officer sat next to Nanfu on the train. Perhaps her camera caught the officer’s attention. It’s also possible that her ticket information triggered an alert in the government’s high-tech surveillance systems, which are used to track hotel stays, train and plane trips, and internet communication. It’s a mystery. But in China, you never know what’s going to happen, and we always prepare for the worst. — Jialing Zhang, co-director