Back to selection

Back to selection

DIY Lives? #LIKE‘s Distribution Journey, Part Two: The End of the Beginning

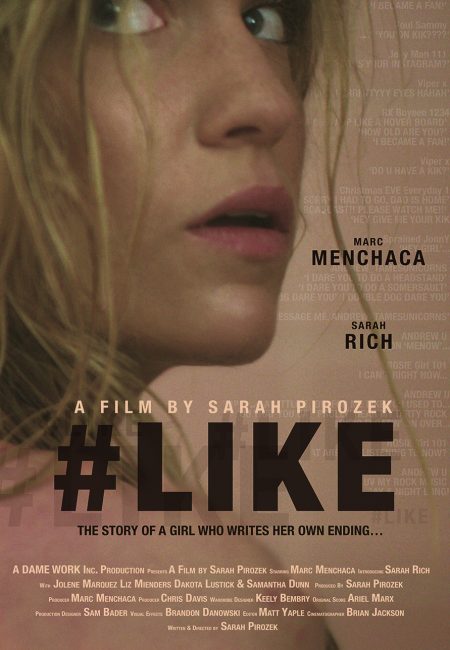

Marc Menchaca in #LIKE

Marc Menchaca in #LIKE On January 26th 2021 my film, LIKE, a feminist noir thriller, debuted on Apple TV, Amazon Prime and others. It has been a long and winding road just to get to the end of the beginning.

Part 1 of my article, published in July, details my voyage into the opaque world of film distribution and the ever-evolving influence of streaming, which had for years been diminishing independent film theatrical box office. But then, of course, live audiences were near-obliterated when COVID-19 lockdowns shuttered theaters. In other words, the theatrical exhibition experience was all but gone until who knows when.

I signed off last time as I was halfway through my festival run, which consisted of live theatrical screenings I traveled to and then, by mid-April/early-May, virtual-theatrical screenings.

As lockdown went on I realized that I was getting many more festival invitations, and I quickly cottoned onto the fact that festivals were thinking of their bottom line. Who can blame them? Perhaps because my film was genre it was more appealing to stream than a feel-good crowdpleaser that needed the theatrical experience. Did I mention it is dark? As one reviewer said, “#Like is dark. Very dark…Think Baise-Moi. Think Girl With The Dragon Tattoo dark.”

So of course it was flattering to be invited to all these festivals, until I figured out I was being was asked each time to make the film available for two weeks with an international link. But were festival promotion and possible awards worth devaluing my true VOD/streaming debut? So I either said, “No thank you,” or I allowed some of the festivals to screen it with tight geo-blocking in place and limited windows of actual screening times….like a festival. About half of the festivals were understanding of this new predicament, like the prestigious Middlebury Film Festival, but some were less polite.

I had to explain to those folks that normally they would have had an audience in close proximity who would watch the film, at best from within a 50 mile radius, for two screenings, one at 2pm and one 8pm (if I had gotten a good slot) on two nights…. Why on god’s green earth would I give away my movie for no payment and allow unrestricted access?

An “anonymous but verified” source shared with me the range of viewers for many geo-blocked festivals has been ten to 100, with smaller festivals hovering in that ten to 30 range. Granted, you don’t know how many people are watching in each household (some festivals multiply by 1.75 to guesstimate viewers), but these festivals are clearly not doing the numbers they would do in person. I would not be surprised to see some of these festivals closing their doors in 2021 and 2022. The pivot to becoming a VOD distributor has been brutal for many of them as it has for the local theaters and movie palaces where they usually hold their events.

I think the festivals eventually understood what I was saying when I turned them down. I quickly got that festivals, theatrical exhibition and digital streaming platforms — formerly three different pies of your film’s revenue-life pre Covid — had become one. They may have been called “peach,” “blueberry” and “pecan,” but they were all just pumpkin and were going to be accessed with just a click. Reputable festivals will respect you, and your work for the most part, so filmmakers in this situation, stick up for your film, protect its value to distributors and push back on unreasonable requests by festivals. The ones I did go with were great experiences: Mystic, where we won Best Narrative Feature Script; the U.K.’s Oxford International Film Festival, where we were screened live in a high-street cinema and won Best Director for me and Best Actor for Marc Menchaca; The Center Film Festival, winning the Gratitude Award; and the Method Fest winning best break-out performance for our lead Sarah Rich; and New Filmmakers Los Angeles , where I got wonderful coverage and had my video Q&A published in Moviemaker.

While I was juggling festivals my journey into the wilds of distribution continued, as did the pandemic. I wrote, directed, and produced this film, but the honest truth is I had no idea how hard distributors, publicists, theatrical bookers, theaters, impact producers, back-end asset creators and ad-sales folks work…There is always more to do. I had met the radiant Nigel Daly of Screen International around five years ago when I was at TIFF, and he was my first pitch. I hit him with my logline (you know like those screenwriting books tell you to) and he genuinely loved it and said, “I can’t wait to see it.” Ha — me neither, mate! The work that went into battling the confidence-gap in funding women’s films, the creative writing, producing/postproducing was surely enough, no? My punk roots had drawn me into the DIY lane, but then comes festival/strategy, festivals, sales, distribution and the nuts and bolts of that. I was truly overwhelmed.

I had already had interest from some distributors early on, but they weren’t right for various reasons then, and during Covid-times, theatrical was moot. I took a big pause — Was the world ending? What did anyone know? I decided to just try to breathe and figure it out.

Then one voice in the wilderness came from Mia Bruno who reached out to me after reading Part 1 of my article. She is a film distribution marketing strategist, impact producer and theatrical booker. She was kindly and patiently listened to me about everything I didn’t know, my fears, frustrations and genuine ignorance until I ran out of steam. She offered to help me out, to guide me through the seemingly impenetrable thicket I was trying to hack my way through on my own.

First thing I did as I got more seriously engaged with my distribution search was look at my poster — artsy… almost French…I had strategically chosen a “not-on-the-nose” genre look because #LIKE is ,after all, what folks call an “elevated-genre” movie, or as publicist Shelley Farmer calls it, “minimalist.” Think Martha Marcy May Marlene. I kept the overall vibe of it and changed the image to draw the viewer in and play on a thriller trope, which, when you watch, you will see is circumvented. I ran it by Mia and she said, “Yup, good idea.” I had my new trailer opening doors, courtesy of Fortress of Evil, who did an amazing job.

So let’s go big picture — who would be best distributor to push the film out there, a company with the right vibe and caliber for my little movie? As I had decided it wasn’t worth my while to engage a sales agent I continued reaching out to folks directly.

Some people ghosted me, and sure, some were rude, but there were those that responded, like Arianna Bocco and Aijah Keith at IFC. Aijah actually called me to apologize for not getting back sooner and to tell me that I had really made a good film, and that it had been discussed at IFC but wasn’t right for their current roster. A class act. I appreciated the outreach and feedback, and as I was beginning to understand, that we are all dealing with the “pumpkin pie” now and how we make or break our capital investments of time and money.

Also the content gap I had hoped for, when all these indies would be snapped up by TVOD and SVOD didn’t appear, and suddenly there were shows like Fauda taking over my recommendations lists — a solid bit of Israeli Law and Order, foreign content eating up American eyeballs. Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate the outreach, but ouch! Indie filmmakers in the US are still getting pushed out — not by tentpoles but now by foreign TV series that are perhaps more evergreen than one indie movie.

Reaching out to other indie filmmakers for advice I spoke to Jeff Roda, who screened with me at The Woodstock Film Festival with his charming ‘80s-set directorial debut, 18 to Party. His is a classic story of an indie film today: the film was on four year-end “best-lists,” and NPR gave it a rave review. He told me about his journey. He had some wins. Susan Jacobs, the music supervisor, had tracked down unreleased demos from the ’80’s by Mick Jones, and they also got an unreleased Velvet Underground song. Amazing. They engaged a huge sales agent and they all thought it was going to be smooth sailing; the buzz was that they were gonna be in Sundance. Submersive, the branding firm, did a fantastic job with the trailer and poster. But they had some losses. As Jeff said, when you boil it down, there are 11 slots for his kind of film. The transition to streaming was underway, Jeff was a director-for-hire on his script, and his producers sold the film, and it is now on Prime. I recommend it, but it goes to show that you never know how a film’s life will unfold.

Jonathan Wysocki — writer, director, and producer of independent films, including his upcoming award-winning debut feature, Dramarama — talked to me. He took a project to Sundance during the financial crisis in 2008, and now he has a film to get out during the pandemic. He shared with me, “The ecosystem was fragile before this… but now it’s really sounding an alarm, loud and clear, and no one really knows what do what do about it. I think the question about whether or not the optics of a bigger distributor really mean anything in the long run is something worth asking.”

Shudder, the streamer —yes, I went there. Good news? They passed, not horror enough for them, but they are interested in it for their library. That’s good. And now this might be a good place to have “the talk” about the birds, the bees, and SVOD. In my many conversations with filmmakers I discovered that I wasn’t the only one who didn’t have a clue about how streaming works, but now I do thanks to Ms. Bruno laying it all out for me. In short, there are multiple windows of release, and they all coincide with a particular kind of VOD.

TVOD, Transactional video-on-demand. Your first window and the highest ticket price will be with iTunes, Amazon Prime, Vudu, FandangoNow, Xbox/Microsoft Store, Googleplay and CVOD, (cable VOD, your cable provider’s ”On Demand” section). These are all transactional platforms where a viewer pays to buy or rent a film.

SVOD, Subscription video on demand (second window) any platform where you are paying a monthly fee to access a library of content like Netflix, Amazon Prime, Mubi, Hulu.

AVOD – Ad-supported video on demand–any place you can watch content for free with ad breaks, like Fox-owned Tubi, YouTube (in some instances), and iMDB TV.

None of this matters if you are not the/a producer on the film, but are a director for hire, but it is good to know. Read Mia’s article here for more advice.

I saw that Julia Kots’s clever film, Inez Doug and Kira, was distributed by 1091, who I had been reaching out to, and after her kind introduction to them they offered me a deal…via a boilerplate email, which was: exclusive distribution; fee a fair percentage of revenue; licensed rights: EST, TVOD, CVOD, SVOD, AVOD, broadcast, educational streaming, airline, non-theatrical. Territory: world. Term: five years.(seems long but one offer I got was 15 years). No MG (minimum guarantee, i.e. upfront payment). Cap on costs, I think after 10K? (Honestly can’t remember the cap, it can go up to 30k for an indie).

I was pleased to hear back from 1091 (formerly The Orchard), but I literally couldn’t get them on the phone. It was clearly a lukewarm offer. As I said we had other offers but nothing I loved, so I decided to roll the dice and go the creative-distribution route with Giant Pictures, who I would describe as a “curatorial aggregator.” I also wouldn’t call them “full service” but just talking to an actual human was helpful. (After working for four years of making a film it’s the least I could ask for.) And Giant will give you 30 minutes of their time probably twice before you sign, but don’t expect any coddling — it’s a spartan affair, but direct. Also they accommodated my sense of urgency to “get it out there already!” Normally it would take three to four months to prep a film for delivery, and they did it for me in under two.

Here are the pros and cons of a distributor v.s. an aggregator. Pros: A distributor will take care of prepping and QC-ing and CC-ing the film for delivery to streamers; they make an actual marketing plan and may allow you input, including overseeing P&A, PR, traditional and digital advertising, social media, etc.; and they pay for all of it. Expenses and effort. They save you a shit-ton of time. Cons: distribution expenses are deducted from the gross before you receive your split. And you don’t own your film anymore for the foreseeable future, and unless it is a break-out hit you won’t see much, or any money either, and you have no ultimate control of how your film is positioned or sold. And no one seems to be offering indies an MG any more.

Giant offered a good split to the filmmaker, with all costs paid by me, up front, and you can get out of the deal in 90 days if you put it in writing. But you will have expenses like: pitching to the different platforms, prepping the film for delivery, and when you go to SVOD, you will have E&O insurance costs and advertising materials and little to no guidance. I could have gone with Quiver or BitMax for a better split, but I was advised that they offer even less sales oversight. Also, be aware, when any of the aggregators are pitching your film, it is not a charming person in a room chatting up her buyers, it is all done via spreadsheets. From what I understand Giant has a reputation for being efficient; their library contains quality films, on the whole; and they are easy to deal with — no muss, no fuss. And on the backend, filmmakers I spoke with were happy with what Giant did with their films, and that they had even received a little payout.

Also to consider is “negotiated placement” for streamers. Which means: where will audiences see your film? At what menu page level will it appear? Most indies won’t appear at all and will be in digital dungeon, only found via a direct link, not drive-by scrolling. Giant’s VP of Content Distribution Nick Savva told me he is “pushing hard” for #LIKE, but what that actually means… is too many layers into the Matrix for me.

Once the contract was signed with Giant allowing them to go out and pitch the digital streaming rights I thought back on speaking with distributor Wendy Lidell at Kino Lorber. She had impressed me with her innovative pivot from brick and mortar to virtual-theatrical screenings with Kino Marquee, early on in the pandemic, and I remembered that I had retained the theatrical and educational rights to my film, which seemed moot until I saw that Lillian LaSalle, director/producer of the lovely doc, My Name Is Pedro, was doing a virtual theatrical run of her movie, with a good slate of theaters showing it. I suddenly thought about theatrical — did I have time to exploit it? I reached out to ask her about her route. She told me that she had hired a theatrical booker but was frank: you won’t make a lot of money doing this but it does get your film’s profile out there. I was bleeding cash so decided to try and figure that out myself too. I has a little under two months to generate some income from my theatrical rights before my digital release, which Giant had snared early on in their pitching process to Apple TV.

I also talked to fabled producer Lydia Dean Pilcher, known for her many films with Mira Nair. A hyphenate like me, she’s now directing — when we spoke her film, The Call to Spy, was just opening, and her other film, Radium Girls, was in its virtual theatrical run. What I learnt from her is that if you own the whole film, as she did with Radium Girls and as do I with #LIKE, you can do whatever you decide is best for you and best for the film. Which is a great way to draw breath when everything is so quicksand-like, with the ever-changing distribution landscape being acted on by COVID and a myriad of other factors. To stretch the metaphor a little further it is a Lawrencian shifting dune for sure.

So I reached out (a little late in the game in early December) to Mia to run the idea of a virtual theatrical by her. She said, “Well you do own the theatrical rights….but you need to start on this, like yesterday.” Suddenly shifting gear I realized I had until Jan 26th to get some more awareness about the film out there and split the ticket price with theaters. I reached out to the Arthouse Convergence Delegate Directory. Seven-hundred emails in one day…brutal.

I also reached out to Meira Blaustein, the executive director of The Woodstock Film Festival, and she was keen to jump on board! How fitting that our first virtual theatrical screening would be with Woodstock after shooting #LIKE there! I put up the link on Vimeo and learned how to build each page and process payments. I chose Vimeo after discovering that Eventive takes three weeks to process and mount any project, and the platform felt frankly clunky to me. Meira sent out the newsletter, and we were rolling. The Film Lab in Detroit picked the film up as did A/perture in North Carolina. We also got lucky with the amazing Laemmele Theater group in LA after Don Franken of The Method Fest connected me to the chain’s president, Greg Laemmele. Be aware that a theater could ask for a certain threshold of sales before a ticket split is in place but not if you host it. For those who watched #LIKE through the theaters, they not only supported the film but also independent theaters and a smaller film festival. For the virtual theatrical, my pal Denis O’Hare was kind enough to moderate a Q&A with me and our stars, Marc Menchaca and Sarah Rich, as an added bonus, the link provided with the ticket price. (You can see it here, password: GoTigers.)

So your film is streaming internationally. Will anyone rent it? Julia Kots said TVOD rentals have been underwhelming. “I have many friends who’d gladly buy me a $4 latte if I asked, but have not rented the movie.” Julia believes this is because film consumption habits have changed. Most people have one or more streamer subscription (Netflix, HBO, Hulu, Amazon Prime, etc) and have no motivation to spend money outside those subscriptions. Gone are the days of renting movies, when there is a glut of “free” content. Julia likes that 1091 has been really transparent; they confirm all costs with her upfront and have a web portal that tracks rentals/sales. 1091 also promoted the film, although not as thoroughly as an outside publicist would have. Unfortunately, Julia’s microbudget could not afford PR for the release. Most sales have been done thru iTunes and Amazon. Once the film goes to SVOD/broadcast, there will be the expense of E&O (errors and ommissions) insurance, which costs between $2,000 and $5,000 and comes out of the producer’s pocket. “The heartbreak is real,” Julia says. “When do you walk away?”

And then we get to PR and advertising… Unless you are happy with the echo chamber of Facebook posts only reaching one’s inner circle get ready for more bloodletting. I hired Shelley Farmer to do digital outreach for the theatrical release, and then re-upped with PR firm Brigade to work with their Guillermo Restrepo again, supplemented by Shelley, who pivoted to the digital release when I realized she didn’t actually do advertising placement. Crossed-wires due to last minute panic. Plan ahead.

Give yourself three months in advance for PR. Time helps. No one told me this. Talk to your PR folks well in advance because by the time I learned I had missed the print window it was too late to get this coverage. I should have pulled the trigger on this earlier. And think of your release dates; mine were two days before Sundance and six after the most contentious inauguration in over hundred years — a lot less than ideal. I wish I had thought a little more about that in November.

We discussed multiple PR outlets and tried to think of clever approaches. The usual trades like THR, Deadline, Variety etc. were what I wanted but the theatrical release killed the “news” element of the streaming release which came as a surprise. So we shopped other outlets, and this deserves its own article, honestly. The changing landscape also has a quicksand effect on expectations around PR. It is a new normal, and I was advised that streaming releases will garner reviews, as opposed to only theatrical, now that theatrical is virtual….But I discovered no, that’s not always the case. By the time they responded the New York Times passed on reviewing the film as it had already had its “theatrical” premiere with Woodstock’s virtual screenings. As a New Yorker, I shed a few tears when I found that out that Manohla Dargis (who I would do back-flips for if she reviewed my film, brush her hair, wash her car, rub her feet — yes she is all that) nor anyone else at the New York Times would be writing about my movie. But we are holding out for mentions in the trades (unlikely) and some online reviews. Guillermo from Brigade made magic last time, so fingers crossed he can pull this out of the fire.

I also hired Submersive’s Alex Dubin for ad buys for #LIKE, whose primary audiences are women and teens to late 20s as well as old geezers with an edge. We decided on Instagram and TikTok to launch the day-of. Suddenly I was thrown into having to understand ad sales? And TikTok! And making 1×1 :15 sec trailers with almost no text, but needing text to allow for silent viewing … and then vertical formats for “my story!” Oh my, brain buzzing — I was trying to learn, and execute, and fast. From my first report I learned that, demographically, our top viewers on Instagram are women 35-44 (43%) followed by women 45-54 (29%) with women outpacing men 86% to 13%. And on Tiktok, women are outpacing Men 52% to 40%. (Maybe a younger crowd, with cooler kids?)

My take on DIY distribution: it’s possible, but it was as exhausting and time consuming as imagined. I wound up pushing out the release date because it was just me doing everything. (Plus, I was developing a TV show and writing another movie.) Then at the last minute I got a call from Giant about mistake on the master — just a few frames of digital noise, but it would be rejected by Apple TV if it wasn’t fixed immediately. So I had to do some “producing” by jumping into action to fix this (during Christmas with my overbooked editor on the road without access to the masters). I was reminded of the power of my strengths as an experienced filmmaker by figuring out how to fix it. (Thank you Brandon Danowski, for stepping in.) The whole thing made me pause to think about this whole industry surrounding us… agents…sales reps…sales agents…huge law firms…aggregators….PR folks…distributors and their staff, front of house and back of house — all of them depend on us for product. Instead of feeling so hat-in-hand, particularly in the indie world, we need to remember as filmmakers that we are their livelihood, their raison d’être.

Hopefully Giant Pictures will be as fully transparent as they promise to be. As Mia Bruno said in one of her many pep-talks, I’m not alone. She reminded me to look at the big picture and to try and weed out what is an opportunity and what isn’t. Don’t settle, and protect your film best you can. I agree with her and recommend the filmmakers reading this considering DIY distribution put together a comprehensive distribution road map plan as early as possible and make plans A, B and C. Everything from a big distributor to a creative, self-motivated distribution plan.

I have personally come across less than excellent consultants and distributors, and I suggest you join the Facebook page: “Protect Yourself from Predatory Film Distributors/Aggregators.” Be aware distribution is evolving very rapidly, and things that worked six months ago aren’t necessarily working now. When choosing to work with a consultant be sure they can name films they worked on recently, can name recent successes, and that they’re not talking about films that came out in 2008 or professional experience from 1992. Consulting is nebulous by nature but make sure there is an actionable plan outlined. There is a whole new wave of women and people of color who are entering the distribution space, and know that not everyone does everything. Some only do impact campaigns, some will do sales but not marketing, etc. There are people like Liz Manashil, Abby Lin Kang-Davis, Rebecca Sosa, Courtney Sheehan, Annie Mercedes of Looky Looky Pictures, who help with impact and outreach campaigns. Wonderful resources for filmmakers, these folks are recommended by Mia as all being smart, engaged and energetic. Firelight Films has grants for people of color to learn impact producing and distribution. She also recommends a newsletter called Distribution Advocates, written mainly by women who are pioneering this space and are doing work, providing advice and help. She advises that one doesn’t settle for a hands-off relationship. Filmmakers deserve more than to sign a deal, walk away and hope for the best.

I believe as filmmakers that we have to take responsibility for our careers and to learn as much as we can about the distribution process. This has been an eye opener for me. It is a leap of faith, but now I have a digital marketing team who are driving people, different audience groups to my film.

Here I am, at the end of the beginning. I am thrilled that #LIKE has gotten some amazing reviews. As it was released out into the world last week I sat front row, with a martini and some truffled popcorn in-hand, like my buddy Shaz Bennett, who just released her movie Alaska Is a Drag with ARRAY. And I had the distinct pleasure to wake up the next day to see my film at the #30 spot in all films on iTunes and #12 on Thrillers. Hope to see you there, and please remember to leave a (nice) review.