Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes Film Festival 2021: Awards, Vortex, Train Again

Vortex

Vortex I typically aim to use this last post as my awards clean-up, wherein I tackle the prize-winning films I didn’t address in my previous dispatches. This year will have to be different, since Spike Lee’s jury trophied many of the films I already found generative enough to have given them space here. Not atypically, though, the panel failed to hand any accolades to the two films that in my opinion were the most laudable among the competition slate—namely, Bruno Dumont’s rapturously off-kilter France, which could have justifiably taken any prize on the menu except Best Actor (although Macron’s unknowing cameo would’ve been an inspired choice—either that or a tech prize for whoever did the green-screening). In particular, Léa Seydoux’s performance as France de Meurs, an ambitious news anchor in the midst of a spiritual crisis, is frankly incredible, as vivid a screen presence as any I’ve seen in years. Likewise, Sean Baker’s manic and intoxicating Red Rocket could have won anything, especially for the unexpectedly great work done by Simon Rex and Suzanna Son, the latter of whom seems destined for bigger things. This isn’t at all meant to shade the year’s big winner, Titane’s Julia Ducournau; her historic Palme is well-deserved and arguably the most responsible choice the jury could have made.

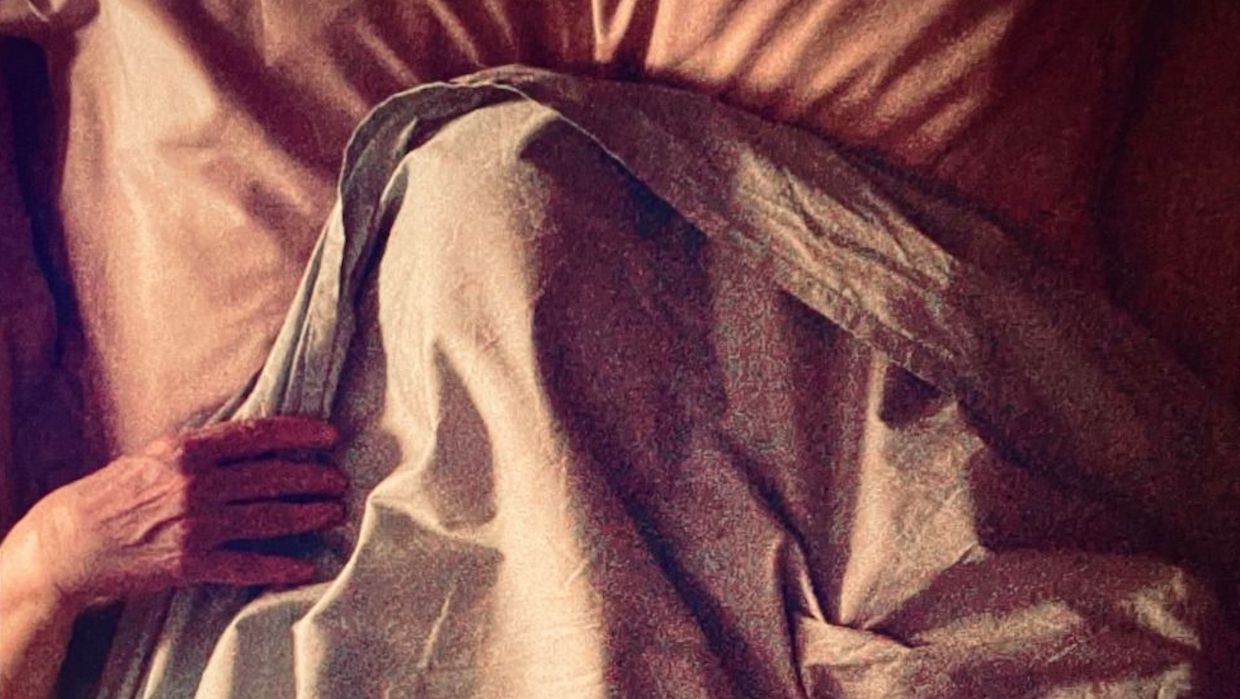

With Dumont, Ducournau, Mia Hansen-Løve and Leos Carax all more or less delivering, it was an especially strong crop of Gallic films Cannes competing for the Palme. It could have been stronger still, what with Gaspar Noé’s characteristically rigorous, uncharacteristically heartbreaking Vortex getting shunted off into the non-competitive Cannes Première sidebar. Opening with a dedication—“To all those whose brain will decompose before their hearts”—the film’s logline on the ground was that it was “Gaspar Noé’s Amour.” If we’re being literal, clearly that designation belongs to Love (2015), though the Haneke comparison makes immediate sense: an elderly couple (legendary giallo director Dario Argento alongside Françoise Lebrun, of The Mother and the Whore [1973] fame) confronts the end of their life together when one of them begins to succumb to Alzheimer’s. The downward spiral is initiated in an early shot of the two in bed, when wide Vortex’s CinemaScope frame gets bisected by a bold black line that permanently splits the frame (and the pair’s unity) in two. From here, both of the 1.2:1 compositions remain fixed on their respective subject, following along in real-time tracking shots as each one goes where they may. Cuts are few and far between, though Noé makes sure to employ his signature blink-cuts so that he can inconspicuously move between takes, if necessary.

While there is a very determined trajectory to the action, Noé says the film was entirely improvised. To some extent, that shows. There are long stretches of time when no one speaks; Argento types away in his office as he works on a book about cinema and dreams that he plans to title Psyché (by pure chance, Psyché was also the working title of Noé’s 2018 headtrip, Climax), while Lebrun runs an errand that she can’t seem to complete. The dual presentation keeps things lively—there’s always something to look at, a juxtaposition to consider—and makes for an impressive mapping of two ongoing spatial and psychological spaces. Moments when the two momentarily cross over into the others’ visual plane are always invigorating, and also poignant. More than Amour, I felt some semblance with the emotional landscape of Leo McCarey’s devastating Make Way for Tomorrow (1937), a film that—like Vortex—was inspired by Japanese melodramas (Ozu for McCarey; Mizoguchi, Naruse, and Kinoshita for Noé). I can’t make the greatest claims for Noé’s dramatic skillset; his strengths are primarily in his expressive consideration of the relationship between the film’s and viewer’s bodies. With his delirious and assaultive Lux Æterna (2019) still flashing in the rearview, it’s encouraging to know he’s locating voids where we least expect him to.

There is no literal vortex in Noé’s altogether calm and patient film, which you couldn’t say about Peter Tscherkassky’s latest experimental short, Train Again, unveiled in the Director’s Fortnight (the fourth of his films to do so) and, as far as I’m aware, the only film that screened in Cannes on a 35mm print (although, alas, my day-after screening was a DCP). Those who’ve already been introduced to the Austrian materialist’s work will be well-prepared for the latest in his ongoing series of films in which cinema feverishly collapses onto and into itself. As many a structuralist before him has done, Tscherkassky invokes cinema’s deep historical and formal ties to the locomotive, and luxuriates in the shocks generated by images of machines going off the rails (a gesture that the film’s own celluloid body replicates ad nauseum). Tscherkassky dedicates Train Again to his compatriot Kurt Kren, who passed away in 1998 and whose work frequently exploited the kinaesthetic potential of rapid editing and graphic matches. Prompted by this intratextual reference, I could see why Tscherkassky would align his project with Kren’s, even if my mind tended to drift more often toward Soviet montage innovators like Vertov and Eisenstein, not to mention the early cinema practitioners (the Lumière brothers, Edwin S. Porter, et al) whose films are explicitly summoned in the maelstrom. Unlike Tscherkassky’s best (namely, Outer Space [1999] and Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine [2005]), Train Again only clicks in fits and starts, but it points to a promise of regeneration—a familiar and storied past that can still be re-presented and revitalized. In a year in which Cannes was trying to convince the world that our fading models of conventional exhibition and storytelling are essential for the industry and medium’s futures, I saw in Train Again an almost resigned last gasp. In that moment, I admit it felt very good.