Back to selection

Back to selection

Metrograph Tribute to the Brothers Young Recalls Heroic Era in Indie Filmmaking

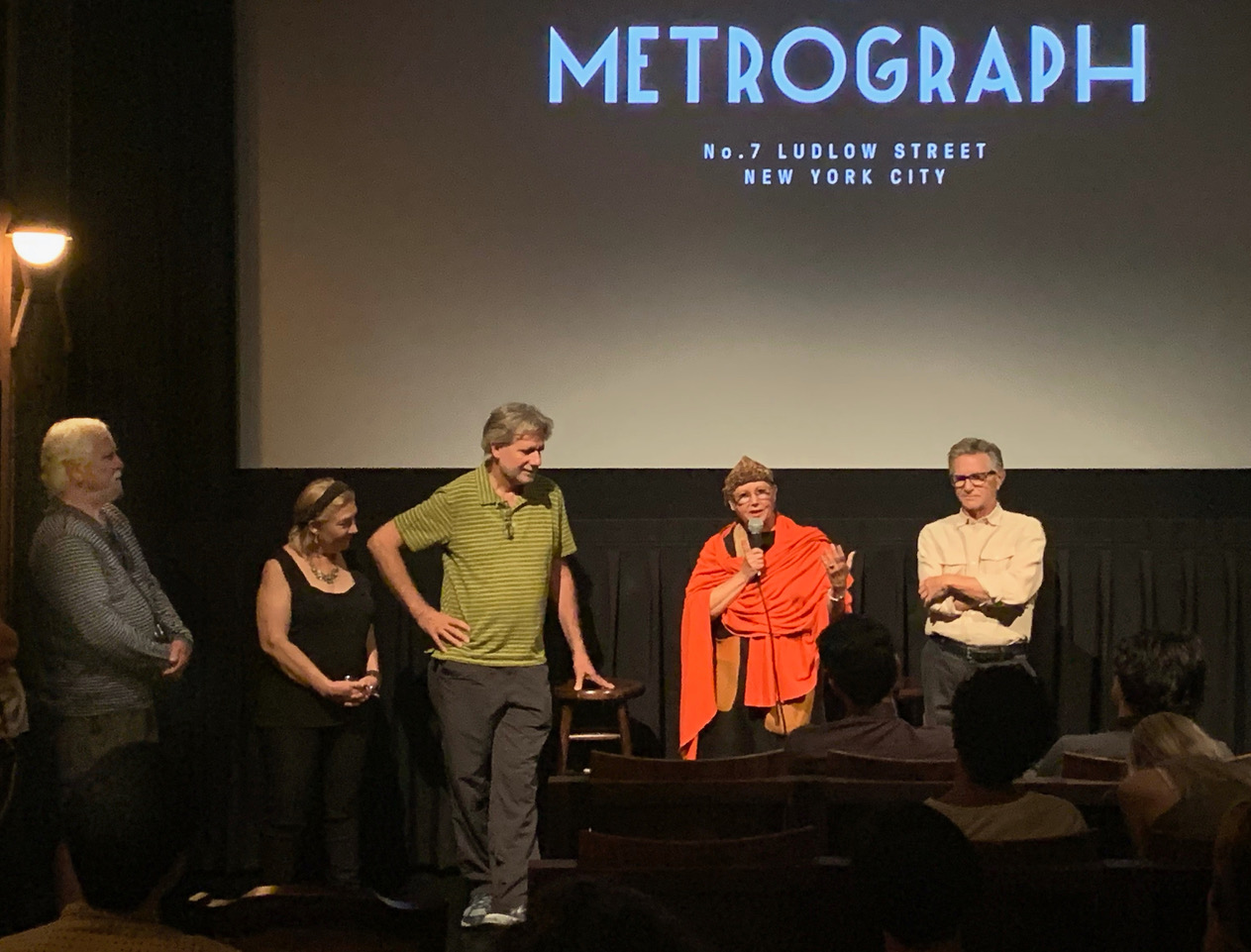

(L-R) Aaton’s Jean-Pierre Beauviala, Willem Dafoe, Irwin Young, and

director Bob Young on the set of Triumph of The Spirit, Poland, 1989.

(L-R) Aaton’s Jean-Pierre Beauviala, Willem Dafoe, Irwin Young, and

director Bob Young on the set of Triumph of The Spirit, Poland, 1989. Since the passing in January of Irwin Young, chief mensch at New York’s fabled DuArt Film Lab, there has been an outpouring of tributes and reminiscences, including a packed memorial at Lincoln Center in May.

But no tribute has been more on point than “The Process: A Tribute to Robert and Irwin Young,” the Metrograph’s recent 24-film series dedicated to Irwin, the lab’s owner, and older brother, director Robert M. “Bob” Young, for the epic contributions they jointly made to the American indie film scene from the 1960s through the 1990s. For the big screen is precisely where the Young brothers left their footprints in the sands of time and cinema.

To attend this ten-day event, curated by Nellie Killian, was to encounter in person the likes of directors Barbara Kopple, Victor Nunez, Claudia Weill, John Hanson, Alexandre Rockwell, Andrew Young, producer Sandra Schulberg, and others, each of whom introduced and later discussed their classic indie works with audiences of enthusiasts not even born when these films were made. In the process, “The Process” unfolded like a nonstop reunion, with spontaneous gatherings of cast and crew, producers and writers, buoyed no doubt with post-pandemic exuberance.

Jean-Pierre Melville (Bob le flambeur, Army of Shadows, Le Cercle Rouge) once quipped that 50% of the success of a film was the selection of the story, 50% was the screenplay, 50% the choice of actors, 50% the choice of the music, and 50% the choice of the cinematographer. “If one of those go wrong, you jeopardize 50% of your film.”

He might well have added 50% for choice of film lab, at least in the era in which these films were made. We’re talking pre-digital here, sprockets and chemicals. A time well before personal computers, desktop apps, or internet. When postproduction meant you had to establish separate business accounts with negative cutters, labs, optical houses, sound mixing facilities and tape houses (for telecine). How good was your line of credit at the bank?

Irwin and Bob had always been close as siblings — their father, Al Young, was DuArt’s founding partner in 1922 — so Irwin enjoyed a front-row seat to the hurdles Bob faced as an independent producer, writer, and director. This sensitized Irwin to the challenges underfunded indies encountered across the board, from financing to production to distribution. With Bob as his sounding board, Irwin committed, as a lab owner, to do what he could to facilitate independent production, at least from the lab end.

Starting in the late 1960s, Irwin began to assemble essential post services “under one roof,” including audio mixing and eventually telecine transfer. This proved remarkably efficient, eliminating a filmmaker’s need to bounce between multiple post facilities and get caught in the blame-game crossfire when something inevitably went wrong. DuArt took full responsibility for the outcome, from soup to nuts. From today’s vantage point of routine digital finesse, it’s frightening to recall all the things that could go wrong in just the film lab alone.

You entrusted the lab not scratch or break your original negative while developing; to develop it to Kodak’s highest sensitometric standards, with properly replenished chemical developers and fixers; to develop it evenly and pristinely, avoiding dirt adhesion or chemical stains; to copy it on well-adjusted contact printers, without weave or poor tensioning; to refrain from abrading or snapping your A&B rolls or original negatives during printing; to optimally time (color correct) answer prints in order to avoid re-dos (more wear & tear to the original negative); to properly expose and develop subsequent pre-print elements like master positives and dupe negatives; and to uphold optimal timing and cleanliness in release printing.

Whew! So many points of potential calamity between developing your initial film dailies and finalizing your answer print for its festival debut. I’ve not even mentioned optical sound tracks!

Irwin was a stickler for perfect results, and filmmakers confronting lab issues knew he had their backs. He never tried to sell them on a below-par outcome — a print with a few timing errors or scratches, a blow-up reel with an optical flaw — in order to spare the lab further expense. But Irwin stuck his neck out further.

No lab, including DuArt, could afford to offer direct financial assistance. Duart, after all, was a business, situated on pricey Manhattan real estate. The motion picture lab business was competitive and relatively low-margin. It was said that you had to love the lab business to stay in it.

In the era of shooting exclusively on film, significant upfront cash was aways necessary to purchase film stock from Kodak or Fuji or Agfa, then to develop it at a lab, then print it or transfer the results to video. Irwin couldn’t afford to do any of this for free, but he could agree to develop the camera negative prior to payment in order to preserve its image quality. Or accept a partial payment in order to release the dailies so that a workprint could be cut for fundraising. Or temporarily defer a bill until, say, a distribution deal closed or a film festival debut took place. Or arrange in myriad other ways to stretch out payments over a long period, sometimes well beyond a finished film’s active distribution.

Beyond the financial, Irwin found additional ways to assist “impecunious” filmmakers, a term affectionately applied by DuArt’s upper management.

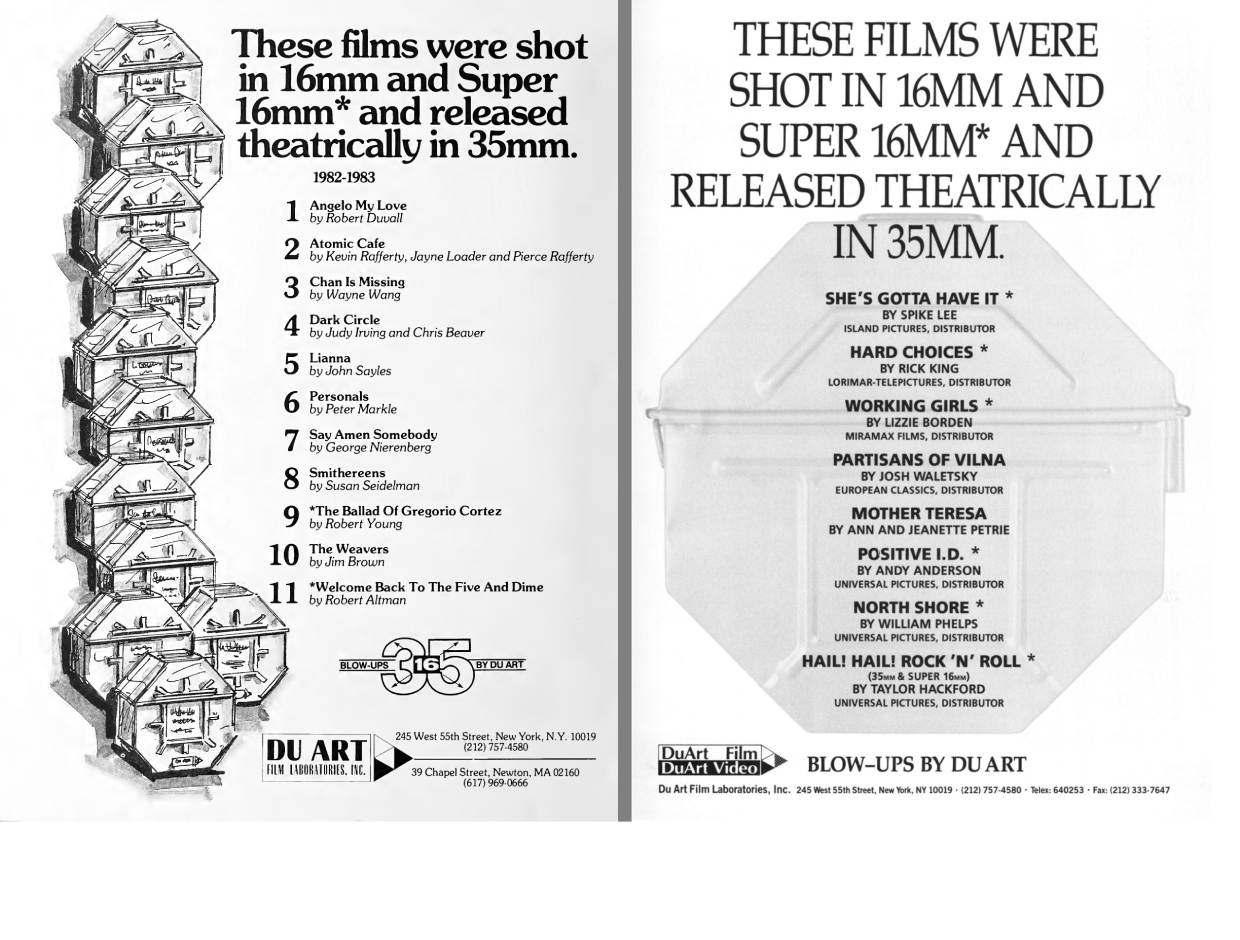

16mm had always been significantly cheaper than 35mm to buy, process, and print. Ditto, the costs of renting or owning 16mm gear compared to 35mm. If blow-ups to 35mm could rival original 35mm in image quality, the hard costs of indie production could drop. Theatrical distributors could ship an acquisition’s heavy, octagonal I.C.C. cases containing 35mm reels and be none the wiser, setting the stage for democratization and the advent of new voices.

Like many filmmakers, Bob Young got his start shooting 16mm documentaries. When he moved to directing dramas, he found that he missed the more intimate scale of shooting with a smaller 16mm camera. He was no stranger to 35mm, having DP’d the classic Nothing But A Man and Michael Roemer’s The Plot Against Harry. Even his directorial debut, Short Eyes, based on the acclaimed Miguel Piñero play, was shot in 35mm. But his next film, Alambrista!, would be shot on his 16mm Eclair NPR and blown-up to 35mm. It won La Camera D’Or at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival.

Bob was aware of developments in Sweden, where cinematographer Rune Ericson had, by 1969, not only introduced the idea of Super 16 but modified and tested the requisite camera and lab equipment. By 1970, Rune had shot an actual production, the story of which occupied much of the June 1970 issue of American Cinematographer. Irwin Young read the coverage and promptly contacted Rune about Rune’s idea for a new 16mm format. It was the start of a beautiful friendship.

Rarely in life do you get something for nothing, but Super 16 was one such exception. Kodak 16mm single-perf negative already existed and it cost the same as standard double-perf 16mm. Developing costs were exactly the same, too, as were the costs of blow-up to 35mm.

And what was the main advantage of Super 16? A blow-up from standard 16mm with a 1.33 aspect ratio required a crop to the 35mm aspect ratio of 1.85, at least where theatrical distribution was concerned, throwing away almost 1/3 of the original image. By eliminating one row of perforations, which no existing camera used anyway, Super 16 instead added an extra 2mm of image to the right side of the negative. When cropped to 1.85 in blow-up, this delivered 56% more original image area compared to a 16mm blow-up to 1.85. Less magnification in blow-up meant tighter grain and better resolution, to better match original 35mm. As I said, something for nothing.

To turn a 16mm camera into Super 16, all you had to do was file out the aperture an extra 2mm on the side opposite the pulldown claw, re-center the lens, and mark the ground glass to accommodate the extended image. That’s what Rune Ericson had originally done with an Eclair NPR, one of the few cameras whose design made this modification feasible. By 1972 a new French camera company, an offshoot of Eclair with the catchy name of Aaton, had picked up on the idea and demonstrated its first prototype Super 16 camera. By 1976, Aaton’s founder and resident genius, Jean-Pierre Beauviala, a friend of Rune Ericson’s and newly minted acquaintance of Irwin Young’s in New York, had produced the first production Super 16 Aaton.

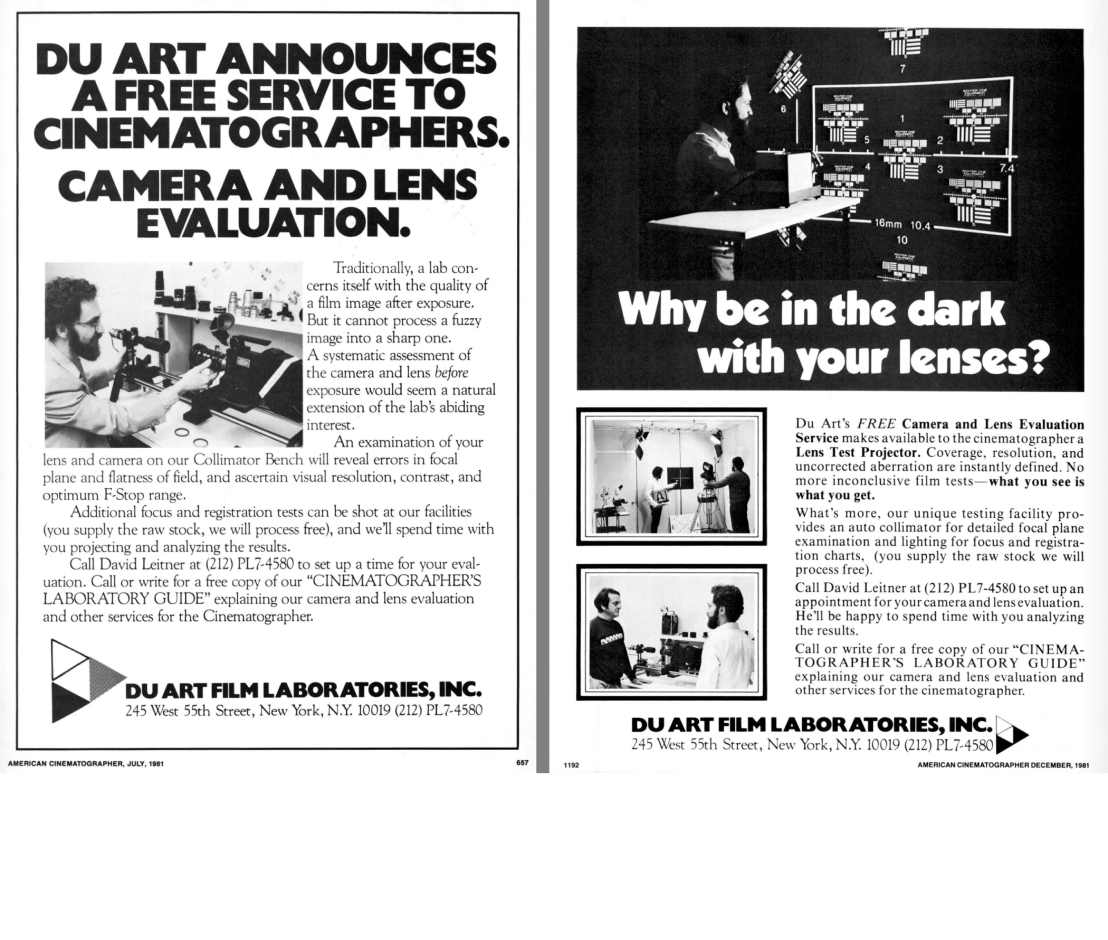

After Alambrista!, Bob Young shot Super 16 tests on a modified NPR, and DuArt made test blow-ups to 35mm. Not long afterwards, DuArt bought a Super 16 Aaton, a set of 16mm Zeiss Super Speeds, and imported into the U.S. the first Taylor Hobson Cooke Varo-Kinetal 10.4-52mm Super-16mm zoom. This was the camera package with which Bob in 1980 shot his first Super 16 feature, The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez. It was later lent by Irwin, gratis, to other indie filmmakers like Spike Lee and Errol Morris. To insure better control over the quality of the 16mm image prior to blow-up, Irwin instigated the creation of a camera and lens testing facility that occupied much of the 10th floor of DuArt and featured the first lens test projector in New York. The idea was to enable filmmakers to assess first-hand the quality of their lenses and condition of their cameras prior to shooting 16mm for enlargement to 35mm.

Through such innovative efforts on behalf of indie filmmakers, Irwin and DuArt were pivotal to the completion and success of an astonishing number of films by iconic American indie directors, including, but not limited to, Spike Lee, Michael Moore, Michael Roemer, Susan Seidelman, Claudia Weill, Victor Nunez, Greg Nava, Wayne Wang, John Sayles, Alexandre Rockwell, Rob Nilsson, John Hanson, Lizzie Borden, Jim Jarmusch, Joel & Ethan Coen, Robert Altman, and yes, even Woody Allen.

On the documentary side, a similarly lengthy list would start with Frederick Wiseman, David & Al Maysles, D.A. Pennebaker & Chris Hegedus, Barbara Kopple, William Greaves, George Nierenberg, Jim Brown, Andrew Young & Susan Todd, Kevin Rafferty, Ken Burns, and countless others.

And not least, the documentaries and dramas of Irwin’s brother, Bob, regarded as the godfather of the American indie scene: Nothing But a Man, Short Eyes, Alambrista, Rich Kids, One Trick Pony, The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez, Extremities, Triumph of the Spirit, Caught, and more.

A preponderance of these films were blow-ups to 35mm.

Film historians should feel free to label this creative explosion of the 1970s through 1990s, with New York as its epicenter and DuArt Film Labs as its nexus, as the American Indie New Wave.

Hats off to the Metrograph for programming “The Process: A Tribute to Robert and Irwin Young.” Given the heaps of culturally significant and award-winning indie films that passed through DuArt in its heyday, I very much look forward to Parts 2 and 3!

David Leitner was DuArt’s Director of Optical Printing and Director of New Technology from 1977 to 1985, hired by Irwin Young to advance DuArt’s 35mm blow-up process and transition the lab to Super 16. He later designed and ran DuArt’s camera & lens testing facility.