Back to selection

Back to selection

“In This Case, Starting at the End Made Sense”: Editor Julian Hart on The Deepest Breath

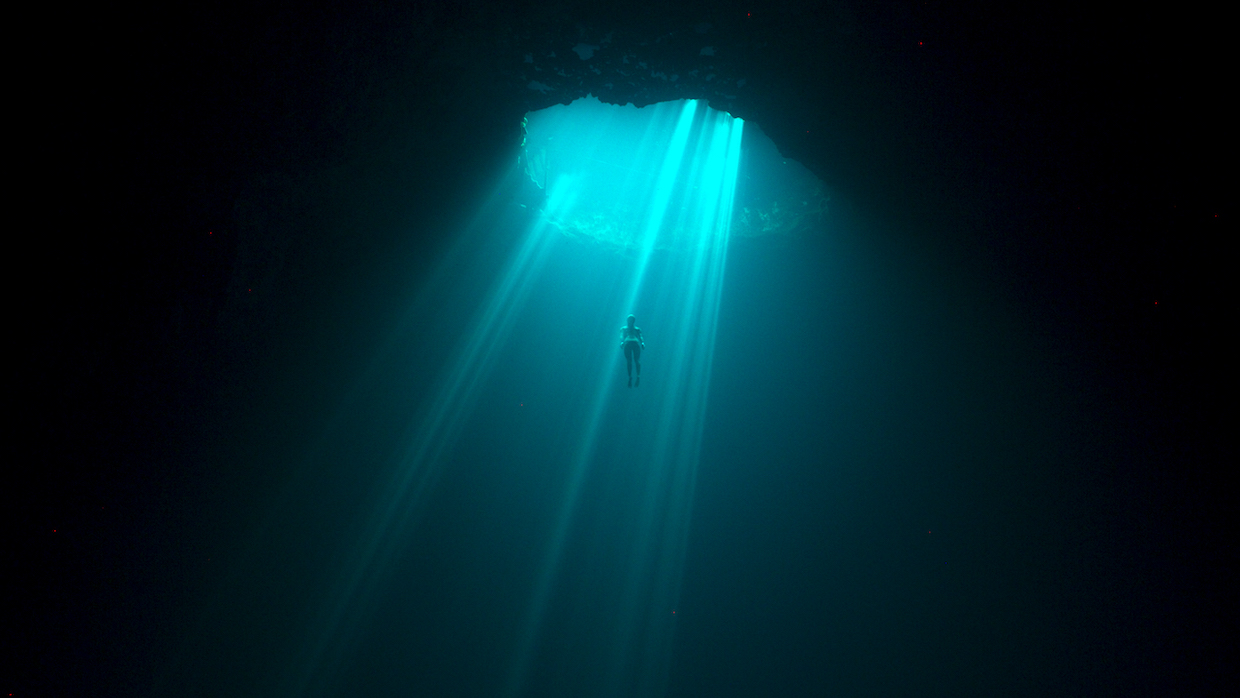

The Deepest Breath, courtesy of Sundance Institute.

The Deepest Breath, courtesy of Sundance Institute.

In Laura McGann’s documentary The Deepest Breath, Italian freediver Alessia Zecchini strives to set the new world record in the extreme sport that entails descending to unimaginable oceanic depths without the use of scuba gear. Due to the high risk of blacking out upon ascension, safety divers like Stephen Keenan are vital for ensuring the safety of those who undertake these challenging dives. Forming an intense bond, Alessia and Stephen set their sights on the legendary Blue Hole in Dahab, Egypt, an 85-foot-long tunnel that plummets 184 feet below the Red Sea.

Editor Julian Hart discusses cutting the film, which featured “thousands of hours of footage” that needed to be whittled down.

See all responses to our annual Sundance editor interviews here.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Hart: I am a long-term collaborator with executive producer Bart Layton, having edited over a dozen films for his company RAW, including his last feature film, American Animals, which screened at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018. I have a reputation as a creative, editorially rigorous and self-sufficient editor. He recommended me to producers John Battsek and Sarah Thomson at Ventureland, Jamie D’Alton and Anne McLoughlin at Motive and director Laura McGann. We hit it off, and off we went.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Hart: It was clear from the beginning that The Deepest Breath’s greatest strengths were the emotion of the deep connection between our central protagonists, freediver Alessia Zecchini and safety diver Stephen Keenan, and the drama of freediving itself. I cut a key element of both components very early on because they offered a beginning and ending.

When you’re confronted with thousands of hours of footage you are looking for a way in. In this case, starting at the end made sense. As a retrospective story we always knew our end point, a freedive off Egypt’s Red Sea coast in 2017. Alessia was attempting to cross the Arch at Dahab’s Blue Hole, the most dangerous dive site in the world. Stephen was the lead safety diver. The outcome is powerfully emotional. Though it took many months to shape the sequence in order to convey the events of that day, the emotional core was set early on with the interviews Laura shot. When you know you have that emotional core, you can be confident the film’s ending will deliver on its potential.

Then I turned to the beginning. We wanted the audience to understand the stakes and difficulties of freediving. The opening frames Alessia’s thoughts about the risks of her sport in relation to a competition dive. I watched hundreds of freedives, but when I found footage that followed Alessia all the way down and up, I knew that was the most effective way we could make the audience feel what it was like to hold their breath and plunge the height of the Statue of Liberty into the ocean depths.

Sound was key to immersing the audience in the experience of freediving. In the dark there is little visual point of reference. It is the sound of the changing depth in the freedives that we were keen to enhance throughout the editing process. Incorporating sound design whilst the offline edit was ongoing allowed us to give the film the space and time it needed for the audio to fulfill its storytelling potential.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Hart: Having set aside a week at the beginning of the edit to discuss key goals in person in London, Laura returned to Ireland to plan the rest of the shoot. As the edit progressed, I would share cuts using the media sharing service Frame IO and we would discuss and meet up again at points in the schedule. With producers based in England, Ireland and the US many viewings were shared via Frame IO, however our most useful viewing was at a screening room with the production team in London. We were always aiming for the cinema, so it was vital to see how the film played on the big screen. As useful as Zoom calls can be, getting Laura and all the producers in one place in person was hugely beneficial in talking through ideas, issues, tone and balance.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Hart: I studied film at university in England for three years, which in time honored tradition, qualified me to make the tea as a runner in a post production house in London! I worked my way up, talking myself into my first editing job in the late 90’s. As an editor, you can only cut what you are offered, so my CV is varied, which I see as a strength, in that it exposes you to a breadth of challenges. Now, I am lucky enough to be offered some great projects. I knew instantly that I wanted to cut The Deepest Breath. The power of the story leapt out of the page on the pitch deck.

Filmmaker: My influences aren’t confined to film, they can be art, music, poetry, prose; anything that makes you feel and offers an interesting method for doing so. I cut both drama and documentary, but my influences for one often affect the other. Episode one of FX’s 2022 drama series, The Bear, is a reference for my current documentary project despite the subject matter and genre being entirely different. In the episode there is a montage that uses an intercut of a video game for dramatic purposes. It gave me an idea for a comedic storytelling opportunity. In terms of drama editors, I’m a huge fan of Joe Walker. In Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival, Joe’s juxtaposition of images of memories and visions was akin to poetry. Films are prose by necessity, but when the opportunity arises it’s wonderful to aim for the poetic, where you can make those emotional leaps.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Hart: Avid Media Composer has always been my first choice. Overall, the editing tools are straightforward and intuitive. It has a reliable media management structure that makes ingesting and sharing swathes of rushes over the internet easy, which was crucial on this project as I edited from home and my wonderful assistants Aoife Carey and Emiliano Lopez were in Dublin and London respectively.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Hart: Rather than one particular scene, it was the diving scenes in general that had the most scope for change. They were not difficult exactly, we just had a colossal amount of dives to choose from all over the world. A select few of the diving scenes required reconstruction inserts to tell crucial story beats not available in the archive. Getting these specially shot elements to work seamlessly with the archive required perseverance over many months.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Hart: I would not say the meaning of the film changed for me in any fundamental way. Laura, the producers and myself were on the same page in terms of what we wanted to achieve. If my understanding of the film were to change it would be in how others react to it. I cannot wait to experience the audience reaction at the Sundance Film Festival to find out what they make of our film.