Back to selection

Back to selection

One Step Ahead: Chinonye Chukwu Interviews A.V. Rockwell on A Thousand and One

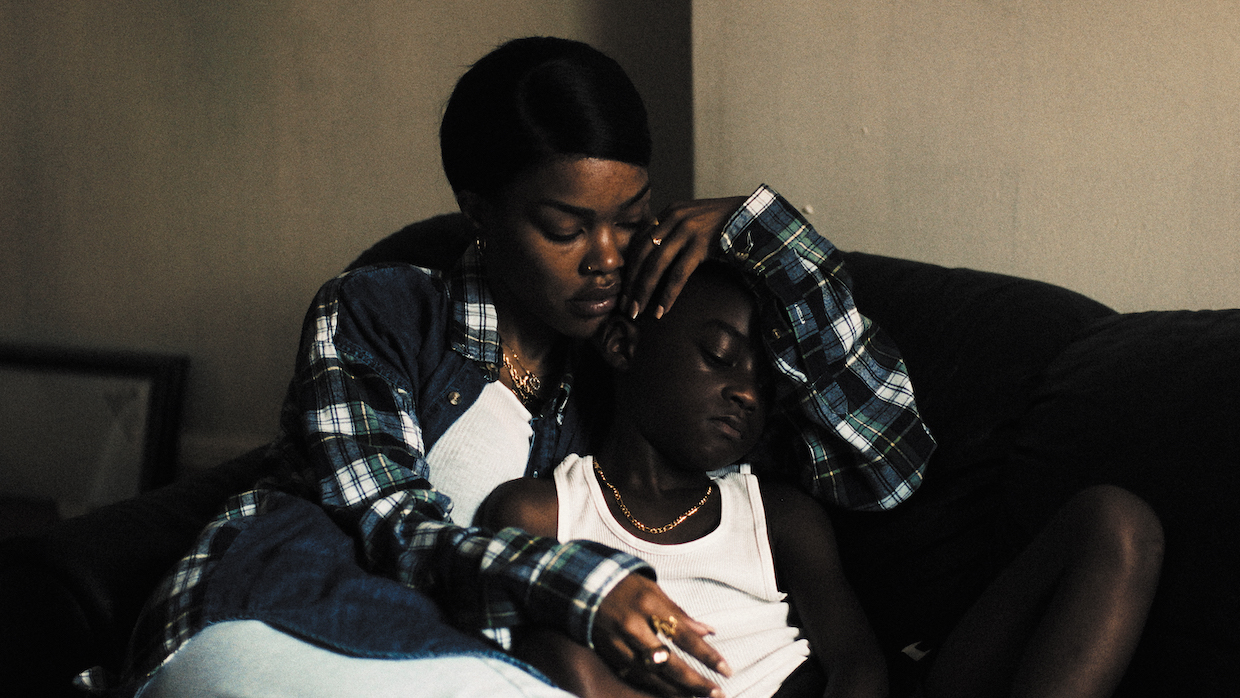

Teyana Taylor and Aaron Kingsley Adetola in A Thousand and One.

Teyana Taylor and Aaron Kingsley Adetola in A Thousand and One. The ever-changing landscape of New York City is the captivating, challenging backdrop of A Thousand and One, writer-director A.V. Rockwell’s feature debut. Chronicling a mother and son’s loving yet fraught relationship from 1993 through 2005, the film incorporates speeches and news reports detailing specific policies of mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg across two decades, a device that serves as a concrete reminder of time passing and stakes rising for the film’s protagonists. Strict jaywalking laws, the advent of stop-and-frisk and increased gentrification initiatives become tangible perils that the Harlem-based characters must navigate, lest they lose the freedom they’ve worked tirelessly to establish for themselves.

After being released from a stint at Rikers, 22-year-old Inez (a spectacular Teyana Taylor, best known as an R&B artist and impressive dancer-choreographer) immediately seeks out her six-year-old son. Terry (Aaron Kingsley Adetola) is now a ward of the state in the city’s dire foster care system (in which Inez similarly came of age), so the mother desperately resorts to kidnapping her child from his Brooklyn quarters to hasten their reunion. With no financial resources, few trusted friends and a police APB out for Terry, Inez leans on her last existing connections and miraculously secures housing in Harlem (their new home appropriately dons the address 1001 due to a missing dash on their front door). She begrudgingly takes a job as a housekeeper in far-flung Queens, leaving young Terry to fend for himself and lay low. As the years march on, so do significant family milestones—Terry receives phony documents that allow him to attend school as “Darrell,” Inez brings a much-needed paternal figure into the boy’s life by marrying on-again, off-again boyfriend Lucky (William Catlett) and Terry blossoms into a preternaturally intelligent yet endearingly shy teenage boy (Aven Courtney at 13, Josiah Cross at 17). When the time comes for him to apply to college and secure an afterschool job, however, the lies and evasions Inez has told to build her family threaten to tear it apart.

Rockwell appeared on our annual 25 New Faces of Independent Film list back in 2019, largely owing to the strength of her short film Feathers. That film follows Elizier (Shavez Frost), the newest student at The Edward R. Mill School for Boys, its ramshackle campus a jarring contrast to its almost idyllic tropical setting. Amid bouts of hazing from his classmates, Elizier flashes back to traumatic memories of his father’s fatal shooting by police. In his 25 New Faces profile, editor-in-chief Scott Macaulay identified a Peter Pan–like quality to the children in Feathers, which Rockwell confirmed: “They face the predicament of not being able to grow up for dire reasons because of the trauma that has affected men of color. As a community, we experience these issues generation by generation and systematically, through slavery, Jim Crow…. Police brutality is the newest dialogue. When people are dying live on Facebook, and it still doesn’t change? A child like Eli who sees that nobody is doing anything about it—how does that affect how you move through the world?” With impressive control and a much larger canvas, Rockwell re-centers these potent musings in A Thousand and One, this time with a concerted effort to address how women of color are often overlooked or unaccounted for within similar narratives.

Less than a month after A Thousand and One won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, Rockwell spoke about her film with fellow Sundance winner Chinonye Chukwu, who became the first Black woman to receive the Grand Jury Prize in 2019 with her death row drama Clemency. Chukwu’s most recent directorial effort, Till, similarly deals with a mother’s boundless love for her son—and the insidious ways that iniquitous systems have failed this country’s most vulnerable populations. Both period pieces, A Thousand and One and Till showcase the ongoing impact of racist policies that were enacted and upheld in our not-so-distant past on Black life in America and how Black women have stepped up to protect those that our culture have heinously deemed expendable. A Thousand and One opens from Focus Features on March 31.— Natalia Keogan

Chukwu: Let’s start from the beginning. Why did you want to be a filmmaker, and did you always see yourself writing and directing?

Rockwell: I don’t know the first time I realized it could actually be a profession, not just something cool and mysterious that people do. I grew up surrounded by so many different art forms that I had a love for, and to me, filmmaking is the ultimate combination of all the forms. At the tail end of film school, I remember seeing The Battle of Algiers and really being moved by that, feeling like, “Wow, this is what movies have the power to do.” They could be as accessible, and make me feel as connected to as my own experiences, as when I watched Spike Lee films growing up. But I could also see the many things you could say about the world, and life in general, with the power of filmmaking. That’s when it really became purposeful for me. I wasn’t as interested in writing. I felt like, “Let me write until I’m at a point where I have access to writers.” I was more interested in visual storytelling, being expressive and looking for ways to be innovative. Over time, I realized I had a very specific point of view, and it was going to be probably harder to find a writer [who] would really give me what I was really looking for than a husband. I don’t think I embraced myself as a writer until I started writing this movie, really.

Chukwu: And looking back, what would you identify as key moments that helped lead to where you are today in your filmmaker journey?

Rockwell: I grew up in Queens, and they had these programs called PL, similar to the Boys & Girls Clubs. Going through that program was really transformative to me because I discovered my love for the arts, period. Then, in high school, we had something similar called Sing. I went to Brooklyn Technical High School, and Sing was basically the biggest arts program we had. I didn’t care about technology or the sciences or anything like that; I just wanted to continue nurturing the creative part of me that I discovered through my interests as a child. I knew what it felt like to be connected to a part of myself in such a pure way of, like, “This is what I love to do. You don’t have to pay me any crazy amount of money. I’ll still be doing this regardless because this is how I like to connect to people and inspire people.” By the time I actually had to figure out what to do with my life, I knew I needed to get back to some version of how those experiences made me feel. I’ve really got to thank my mom, too, because she’s the first person who really told me, “Oh, you’re an artist”—when I was really young, like five, six. She was the first one who saw it. I remember I had a teacher who said artists don’t get recognized until they’re dead, so I was like, “Well, damn.” But [my mom] was the first one who really instilled that in me and tried to embrace it, so I have to give her all the credit.

The last thing I’ll say is, in high school, we had a video class. I don’t think it taught me a lot about filmmaking in the way that gave me clarity of, “This is what I should do for a living.” But I remember one project. We had to tell a story through photos, and that particular project was about Black people and the beauty of Black life over time. And I remember everybody in my class was so moved by it. Everybody had these really silly, humorous projects, and I came with this very serious piece celebrating us. And I loved that feeling, being able to move people. So, it was like, “Here’s something that I love that I could not only do for myself, but for other people.”

Chukwu: You wrote and directed the short Feathers in 2018. Can you talk about that jump from shorts to your debut feature? What was that experience like, and what were the surprises or challenges you navigated?

Rockwell: By the time I made Feathers, I could’ve already started making features, but I needed to get that story off my chest. I’m really happy that I did because it was so well embraced, but it also gave me clarity in where I went next as a writer. I wrote a story for young Black men of all ages to show them how much I loved them. But by the time that I went through certain experiences that made me want to make this film—I was like, “Damn, has anybody ever done that for us? Have I ever seen a Black male filmmaker honor us in that way?” Recognizing that was just part of a bigger recognition and hurt that I felt about just how overlooked we are, even by the people we fight for the most. If they weren’t going to honor us, I wanted to do that in my own way—not just African American women, but underprivileged Black women, especially, because I do think they have the hardest fight. They give the most but get the least. So, I really wanted them to feel that love.

Making [Feathers] definitely influenced the jump that I made with this movie. You’re still telling a story, just way longer. That being said, because a movie is an expanded version of a short, so are all of the problems and obstacles, and the intensity of what you have to overcome. So, it was really challenging and really tested me, but I appreciated the ways that it made me grow as a filmmaker and also as a human being.

What I thought was going to happen was that I was going to make Feathers, take it out to festivals, see what kind of attention and opportunities I’m able to get from that to get my first feature made. But this all came together before I had even debuted Feathers. I finished the short, then did a private screening out in L.A. I was living in New York at the time, where I’m from, so I came out and invited a bunch of people, including some producers I’d just met from the three companies that ended up making the movie: Sight Unseen, Hillman Grad and Makeready. I met these people the way you meet so many people, at generals. I didn’t have any heavy agenda except for seeing if we were people that connected. Obviously, I had this short that I was really excited about and proud of. And I was like, “Yeah, come through, no pressure.” So, the fact that they actually came out [to see it], I was so delighted. Then, they approached me and said, “How can we get involved? What do you want to do?” I had just started developing this idea, so it’s not like I had a fully fleshed-out plot or anything. They really were with me from the inception and building of this story from the ground up. Once we developed it and got the screenplay where we wanted it to be, we went out, approached distributors and Focus got involved. And yeah, the rest is history.

Chukwu: Can you talk about what informed your directorial vision for A Thousand and One? And what was your process in developing that vision and working with your cinematographer?

Rockwell: I wanted to tell a story about a family versus the city. I was trying to understand what happened to New York City as I knew it, and what was happening to communities of colors that felt targeted—trying to tell that story but also parallel it against what my experiences have been or experiences other Black women have [had] coming of age in this environment. What people that see the film understand by the end is that this was a story about a Black woman who was desperate to be loved, not just needed. So, I was really trying to crack that story, but also trying to say something about New York City. How do I feel about a city that I love so deeply, but it seems like it doesn’t really love me? This place that’s supposed to be a part of my DNA, how do I reconcile the fact that it doesn’t even want my people here and, looking back through history, probably never has? And also, to explore how hard it is to keep Black families together, and the different things that try to rip us apart—not only external factors but also internal dynamics within the family that make it hard for us to overcome what society throws at us.

I love that New York City has this walkable history. That’s true of so many great cities—Paris, London, Rome—but New York City doesn’t fully appreciate that. The turn of this new century was the first time that you saw a lot of historical architecture being bulldozed down. It’s not just a city constantly in progress, but there’s this really dramatic shift that’s happened

instead of revitalizing and building on what’s there. Even small things like windows that allow people to see outside and communicate to their neighbor, you don’t have that because everybody’s enclosed in glass. It just feels more anonymous. It’s not being designed like how a city is supposed to be experienced. It’s not a city that is supportive of mom-and-pop shops—now, you have your Old Navys, your Bed Bath & Beyonds, your Whole Foods. There’s always been space for everything in New York City, but now I think it’s bigger than gentrification, what’s happened to New York. So, we really tried to capture the landscape in a way that showed that change, how it went from being a very colorful brick city to being very steel and glass, kind of stale and lifeless. Even through the sound: You hear the sounds of a neighborhood and feel that vitality that Bloomberg speaks of in the film. He talks about protecting it, but New York City is getting quieter and quieter. The sound of gentrification is, like, silence, you know? So, I tried to keep all of these different things in mind: What makes New York City what it was, but also makes the city a city in general, and seeing that being erased and that whole process—whether it’s policies or just the look of the city itself, how all that comes together in a way that impacts these characters from different places. Some places it’s more subtle and insidious, but it’s all influencing their life together.

Chukwu: One of the aspects of your visual language that speaks to this gentrification was, whenever there’s a transition in time, there are those overhead pans as well. How did you develop that language? What was the process in holding that language with your cinematographer, as well?

Rockwell: In a lot of those more macro shots, you’re seeing the landscape of New York City, and not only do you see that progression of old versus new but also what makes New York New York: that grid. The grid layout of New York City is so indicative of setting the foundation of everything that this city became. I mean, it is still the greatest city in the world, so being able to acknowledge the bones of New York through that layout as we hear about all the changes taking place was really important to me. As much as possible, I wanted you to feel immersed in New York City and the experience of it, right down to little pieces of conversation. Also, historically it was so important to hear from the people that actually created that vision for what New York became. So, I really wanted to hear Mayor Giuliani speak about New York in his words, Mayor Bloomberg speak about it in his words. I think a lot of people don’t realize that stop-and-frisk was a Giuliani policy. So, the movie [is bookended by] the beginning of his time in office, and what his vision was, and goes to the end of his time in office in 2001. That last quote that you hear about stop-and-frisk, I pulled that from him explaining stop-and-frisk. We couldn’t get [the actual audio] cleared, but it was his policy. I think it was really important for people to know that because people always associated it with Mike Bloomberg, who just took that process from zero to 60. He really magnified it.

All of these things played into each other to build a new city that ultimately was not really designed for my characters. You have to see all the things that created the stage for that. And for Giuliani to speak of change but then spend the whole arc of his time in office pretty much trying to get rid of people like Terry and Inez and Lucky, you see the step-by-step process: “Let’s start literally taking them off the streets, whether we’re getting them for petty things like jaywalking, whether we’re changing their neighborhoods, whether we’re targeting them through police brutality and harassment. Let’s start there and continue from that point to do everything we can to transform their communities.” They did create change, but it wasn’t designed for this group of people.

Chukwu: How did you shoot the film in New York City and still make it look period from the ’90s? Because like you said, New York has changed so much. So, where the hell did you go in New York that still is like that while shooting in 2021?

Rockwell: It was incredibly difficult, but not because of that; it was because of COVID. It’s already hard making your first film, and then COVID—forget it. So, as a person who knows the city so well and is so observant of it, I leaned on that lived-in history. That traditional, iconic architectural New York, it’s still everywhere—at least, it was in the summer that we shot it. If you thought gentrification was going crazy, it went on steroids over the pandemic. So, I do feel like if we would’ve waited even just a summer longer, I don’t know if we would’ve been able to make this movie in New York.

Leaning on what was historic was my starting point. From there: Where do we put the camera in order to give attention to that exclusively and not what’s around it? Sharon Lomofsky, my production designer, was so integral to this process, like re-doing awnings when we needed to, dressing the set in the right way to build on what was there and remove the elements that did not need to be there. We really had to be collaborative as a team. Visual effects helped a little bit, too. It didn’t solve everything, but it was the last element that helped tie it all together.

Chukwu: Teyana Taylor is the star of your film. I listen to Teyana’s music all the time on repeat. I had never seen her work as an actor, and I was pleasantly surprised by how naturalistic her performance was. Can you talk about what informed your casting of Teyana and about working with her?

Rockwell: I had to be very thoughtful about casting Inez. As I was writing the screenplay, I realized I needed somebody who was going to be able to connect with this character from a very pure and truthful place. For this type of role, it would’ve been really nice to get some A-list actress, and there’s so many that I’m a fan of. But that purity of feeling like, “This is a woman who either knows this woman in real life [or] has been this woman in some version of her life,” I needed to feel that connectedness in the actress and that it wasn’t performative. There wasn’t some judgment from looking down on her. Also, there’s just a part of it that you really believe that she’s the New York City woman in a way that’s effortless. I felt like that was going to be harder to find. How can I find somebody that has the chops, but also can give me that real purity I’m looking for?

I felt like it was in the best interests of the project to remain open to who could be Inez, but really only see people willing to read for the role. We saw tons and tons of women, myself and the casting team, led by casting director Avy Kaufman. Teyana’s name might have come up, but I hadn’t seen her in much of anything. I didn’t see anything that she’d done before that gave me enough information to really know what she could do as an actress. So, I kind of wrote off the suggestion of her taking this role. But she did a tape like everybody else did a tape. When that came to my inbox, I remember seeing her and, having seen so many women up until that point, I felt the difference in her take versus everyone else’s. She was so raw, and I appreciated that. I hate when people feel like either you give the character or you give yourself. And you can tell that she understood this character, both as an actress and as a human being. Then, I met with her, worked with her a little bit. We did some scene work to make sure that she really can perform, not just bring herself. She’s actually bringing the strength of an artist. She’s never done something as demanding as this was, and I did warn her that it was going to be very different. Overall it was a collaboration that challenged both of us but was still beautiful, and I think we both grew from it. I was so grateful, not only in the way that she committed to the role, but for the connection we had. I was able to give her small pieces of information, and she would take it a mile. I needed her to trust me as the director, but I had to trust her as well, letting go of the character and letting her take [her to the places] that she wanted to go with it.

Chukwu: When I was making Clemency, I lived so far away from this industry and was very much cultivating my craft away from Hollywood. I didn’t even know the difference between an agent and a manager. There were agents calling me or trying to reach out when I was making Clemency, and I ignored them because I was like, “I’m going to focus on my craft.” And it took my producers to intervene and be like, “Girl, respond.” So, the success of Clemency thrust me into the business of filmmaking. While I’ve been spending most of my life cultivating the craft of filmmaking and myself as an artist, these last several years have been a big learning experience for me about understanding the industry and business politics, and also navigating success, because I’ve been so used to rejection and that uphill climb. I was terrified when I didn’t have to keep climbing up it, when I could just chill and plateau for a second. How has it been navigating your success? And how have you been navigating the balance between the art of filmmaking, and the business of filmmaking, since your win at Sundance?

Rockwell: As you describe, you’re so used to a certain journey. So, when it’s this dramatic change, it’s like you have to form a new identity. In some ways, I have already been on that journey. For so long, I was working up to a point where I could just focus on feature filmmaking. Now that I’m here, it’s weird, because it’s just the beginning. So, I have been trying to take my time re-envisioning myself because of that. I’m not putting a whole lot of pressure on it, but I’m realizing there is a newness here, new goalposts and ways that I have to envision how I’m looking forward—which is also exciting, you know? So, I have been looking for fresh ways to inspire myself. I’m so grateful that certain aspects of the journey have fallen away. The business side of things, it’s always there and I think it is important for people to understand—if you’re a filmmaker, you have to understand your craft, but you also have to understand how the business works. You can’t be naïve. But I tried to stay balanced in how I look at it: understanding the landscape, understanding where I stand within it so I can navigate it with clear eyes.

Chukwu: Do you love both screenwriting and directing? Do you see yourself doing both or do you want to just focus on directing?

Rockwell: Once I embraced myself as a writer, I was like, “Oh, yeah.” Basically for a long time I wasn’t accepting that this is actually a part of who I am. Once I did embrace it, I was like, “Oh, this is perfect. This is me.” That being said, I always will be continuing on this journey as a writer-director, but I don’t close the door off to collaborating with other writers if something I really connect with breaks through. We’ll see. Because I want to have a long career ahead of me.

Chukwu: You absolutely have a long career ahead.

Rockwell: But there’s opportunity to navigate through so many different ways, and not just what I am writing and directing. I’m hoping to produce as well as I move along. I’m just keeping the door open to all possibilities.

Chukwu: I always ask this last question because I think it’s really important. It’s about joy. And when I say joy, I’m not talking just about happiness, but about a peace and light inside of you that can never be diminished by anyone or anything good or bad happening outside of you. Are you in a space of joy right now? And how do you maintain that joy and your sense of self amidst this blooming success?

Rockwell: Just being able to do this, it’s quite a privilege that I can’t take for granted. As I said at the beginning of this conversation, I’m just doing what I would’ve been doing anyway, the same type of thing that I wanted to do in my free time when I was a child. I’m literally the same person living out the same way of expressing myself. So, the fact that I was able to find that thing for me is really special, and I have to not take it for granted. And that is my joy. I chased my joy and made sure that it was something that I was going to carry with me for the rest of my life. And so far, I’ve been able to, and I’m really fortunate for that and fortunate for this new chapter and all the different things that I get to experience as this journey moves forward.