Back to selection

Back to selection

Producer Data: The Numbers Don’t Lie (The Truth about Independent Film Revenue)

Alden Ehrenreich and Phoebe Dynevor in Fair Play

Alden Ehrenreich and Phoebe Dynevor in Fair Play Last fall, desiring information to aid our own filmmaking careers, we launched an experiment to see whether we could obtain hard data on independent film revenue. Having experienced firsthand how difficult it is to get this information, we created a Google form and asked filmmakers to self-submit not just their feature film top-line revenue data, but thorough, detailed and specific numbers on everything from their budgets to best- and worst-performing revenue streams to cast to how much their films made in gross and net terms. From the details of the 104 submitted films, we have drawn critically important—and many surprising—conclusions.

For our own part, the information we gleaned will, in large and subtle ways, alter the way we put together our future films. But there was another reason we launched this experiment. In addition to wanting this information as filmmakers ourselves, we spend a lot of time talking to other filmmakers. Liz managed the Creative Distribution Initiative at Sundance Institute and now works as a sales and distribution consultant. Naomi teaches classes and consults with filmmakers on indie film development and financing and, in her work as one of the founders of The 51 Fund, interacts with many filmmakers who are trying to get their films financed. Between the two of us, we encounter filmmakers at the beginning and end of the herculean process of making a film.

Informed by a combined 20-plus years of experience in the industry, we are increasingly concerned about the disconnect between what many filmmakers think can happen and what we know the reality to be. Week after week, we listen as filmmakers earnestly explain to us how they believe making a film for “as little as $250,000” makes it a near certainty that they’ll recoup their investors’ money. “CODA sold to Apple for $25 million,” they say with straight faces, “and my film is also a coming-of-age.” We ache for these filmmakers: We, too, have been suckered into these illusions. But seeing the actual financial state of independent film as clearly as we now both do, it feels increasingly critical that we confront how dire a situation the field faces. We say this not because we wish to discourage anyone, but rather because we care so passionately about a brighter future for independent film.

At this moment, there are only two possible paths for an independent film. The first is what Naomi refers to as the “golden elevator.” A project that manages to get on the golden elevator is very likely to bear out a filmmaker’s wildest dreams: premiere at a top film festival, big dollar sale to a streamer, maybe an Independent Spirit Award, distribution by NEON or A24. These high-profile stories keep the rest of us dreaming as the filmmakers breezily explain in interviews a charmed path up into the stars. But there are only a tiny number of highly elite and tightly gate-kept tickets onto that golden elevator. A place in a highly prestigious lab might get you on board (though certainly isn’t guaranteed to do so). So may the attachment of a hugely famous actor (not a sort-of-famous one) or the full-throated backing of WME or CAA (but only if they’re really pushing the project, not just casually attached). For a good example of the trajectory of a golden elevator film, see this year’s Sundance success stories, such as Fair Play, produced by the high-profile team of Ram Bergman and Rian Johnson through their new production company, or the trio of debut features financed by A24 and written about elsewhere in this issue.

Critically, in almost every case we’ve witnessed, a project gets their ticket onto the elevator before—often well before—the film is actually even made. One of the most pernicious and lingering myths, we think, is that it is possible to get on that elevator at a higher floor—that if you can just scrape it together and make a truly brilliant film you can get into that festival or sell to a streamer for serious money later. In our experience, this is simply not true today. Certainly, there will always be unicorns, but for the rest of us, the reality is that, if you are not on that elevator at the basement, the chances that you will gain access to any of these outcomes are vanishingly small.

We call the non-golden elevator films—the actually independent films—“free-range films“ (a term coined by director Maria Nieto) because they are made fully outside the institutional industry apparatus. In the current landscape, these films find themselves scrambling down a well-worn set of uninspiring distribution paths. Out here, in the land of mid-level film festivals or no-one’s-ever-heard-of-them film festivals, filmmakers encounter unrealistic projections from predatory distributors or the candid and depressing truth from honest ones that recoupment is near impossible after platforms, agents and distributors take their pieces of the pie. This is because content has been and continues to be devalued on a daily basis as audiences are sold more and more SVOD and AVOD platforms that allow them unlimited viewing for small monthly fees—fees effectively subsidized by low license fees to creators—that pale in comparison to the true cultural value of all the films in those libraries.

All of the above we had previously gleaned from our own experiences. But it was difficult to figure out where to go from here since, without actual revenue information from free-range films, it has been impossible for us to model our future films’ revenues or instruct other filmmakers on their own realistic revenue potentials. This difficulty has been partly because revenues of free-range films aren’t openly reported anywhere and partly because filmmaking teams are almost always reticent about sharing their actual earnings numbers. The latter difficulty in getting accurate information is both because the industry actively discourages us from sharing this information and, we believe, because few people want to admit how dismal their numbers actually are.

In the fall of 2022, we opened up our online survey, allowing filmmakers to submit anonymously if they chose, and were delighted when 104 responded. While it would be ideal to have access to substantially more data, this initial group is at least a starting point from which we can begin to extract some concrete answers about the state of free-range films. Of course, as with many studies, there’s inherent sample bias here in terms of who chose to answer the survey and which filmmakers even learned of it. (See this article’s sidebar to learn about several of the respondents and their particular revenue paths.) That said, the films in this data set went to recognizable, if rarely top-tier, festivals, were distributed—in many cases, internationally—and are available for viewing on multiple recognizable distribution platforms.

Because we believe that we are all better off having as many filmmakers as possible conducting experiments with different distribution/revenue models based on real data, we are sharing the full data set with everyone here.

What follows are four lenses through which we looked at the data to try to draw out information that could enable us—and other filmmakers—to make better, more informed choices on future films.

Is anyone actually breaking even and/or making money on their films and, if so, is there a budgetary sweet spot to do that?

For the purposes of meaningfully answering this question, we only looked at the films that have been released since 2018. The revenue landscape has so substantially changed since then that including films released prior to that year would unhelpfully muddy our results.

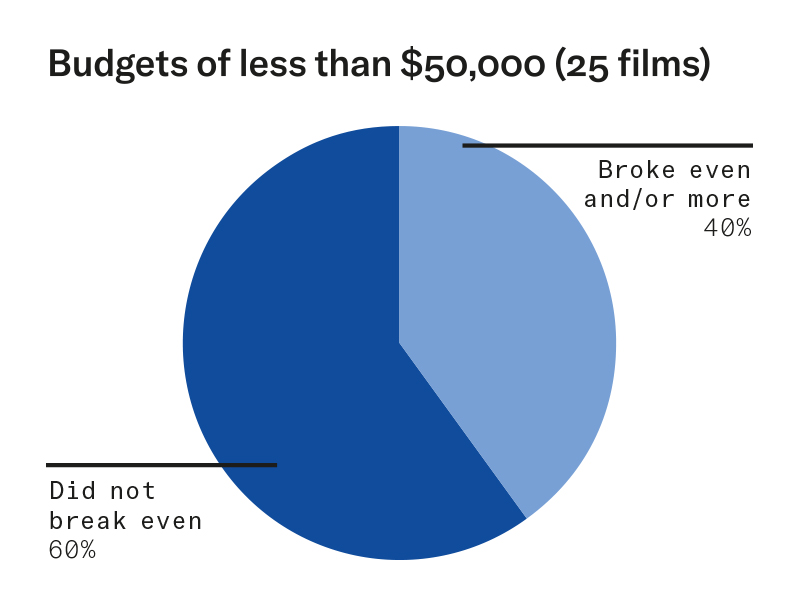

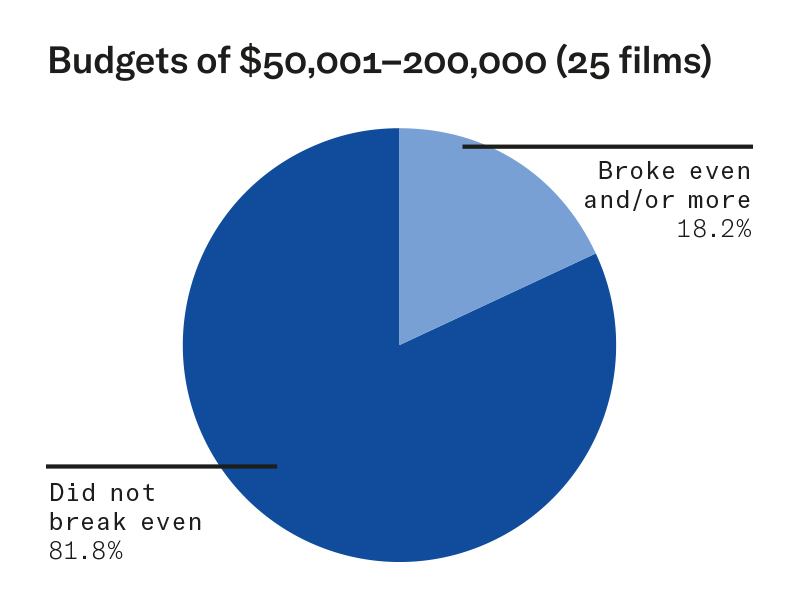

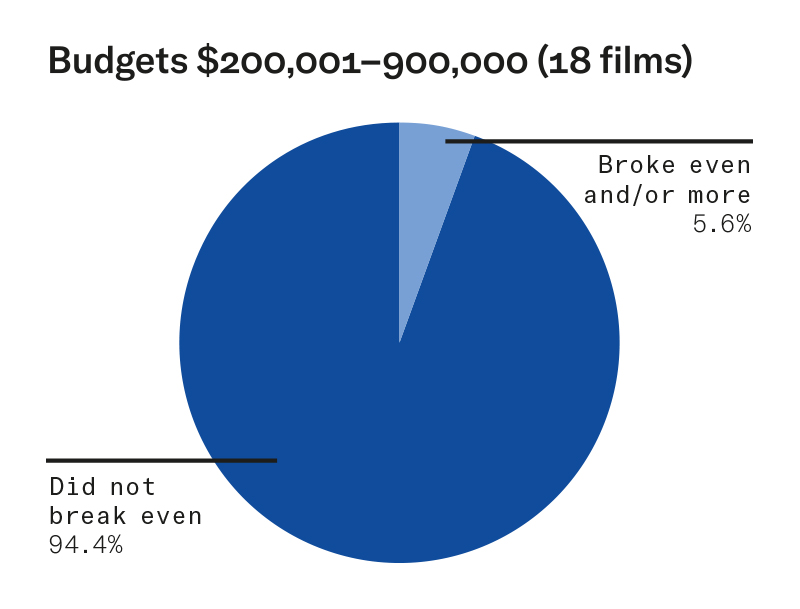

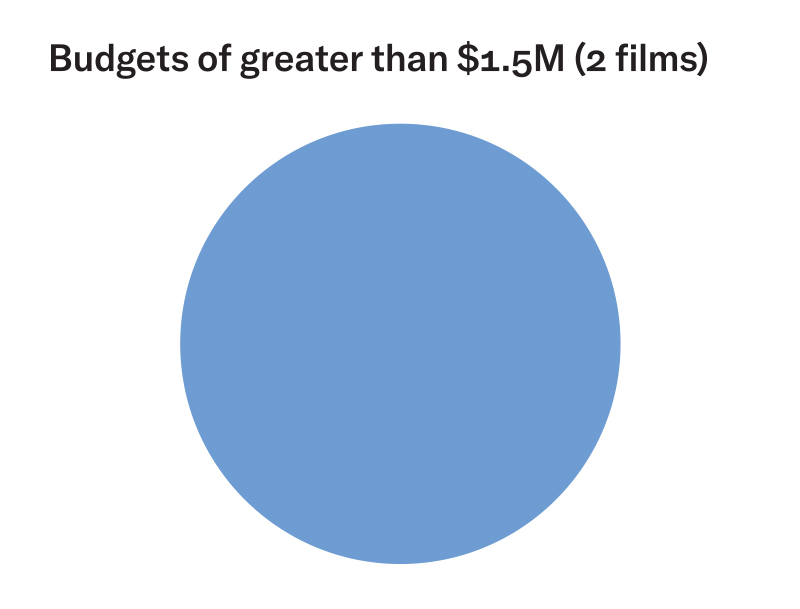

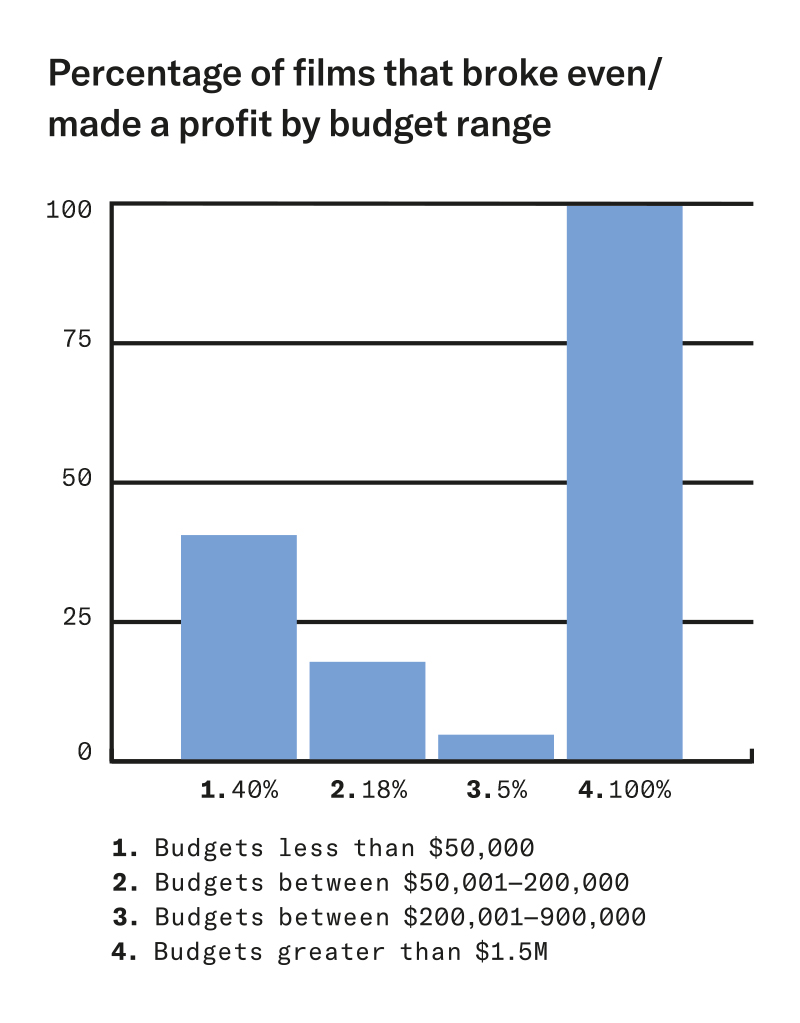

Looking only at films released from 2018 to 2022, here is the breakdown of how films across budget ranges fared in terms of breaking even and/or making a profit versus not reaching the threshold of breaking even. We did not receive any results from films made for $900,001 to $1.5M, which is why that budget range is skipped in our charts.

The caveat is that our sample size is not large or representative enough to draw conclusions about the overall likelihood that a given film will make money in a given budget range (you cannot, for instance, say that a film made for less than $50,000 has a 40 percent chance of breaking even and/or making a profit).

What is extremely useful, however, is to look at the trends across the budget ranges because they demonstrate an important principle we’re calling “the budget/profit donut hole.”

As we suspected, in the current revenue landscape there are big deals available for the larger films—likely golden elevator films—but for everyone operating below that level, there is so little revenue available (at least, revenue that makes it back to the filmmakers/investors) that, if your goal is to break even and/or make a profit, the revenue market suggests that making your film for less than $50K is your best bet. If you make it for less than $200,000, you have a modest, though not great, chance of recouping or turning a profit.

Probably the most stunning and salient piece of information to be drawn from these data, however, is that, of the 18 films released since 2018 with budgets between $200,001 to $900,000, only one of them was able to break even/make a profit. If the past five years are any indication of the present/near future situation, if you are a filmmaker looking to make a movie and hope to break even/make money, the most dangerous zone is the budget donut hole of $200,000 to $900,000.

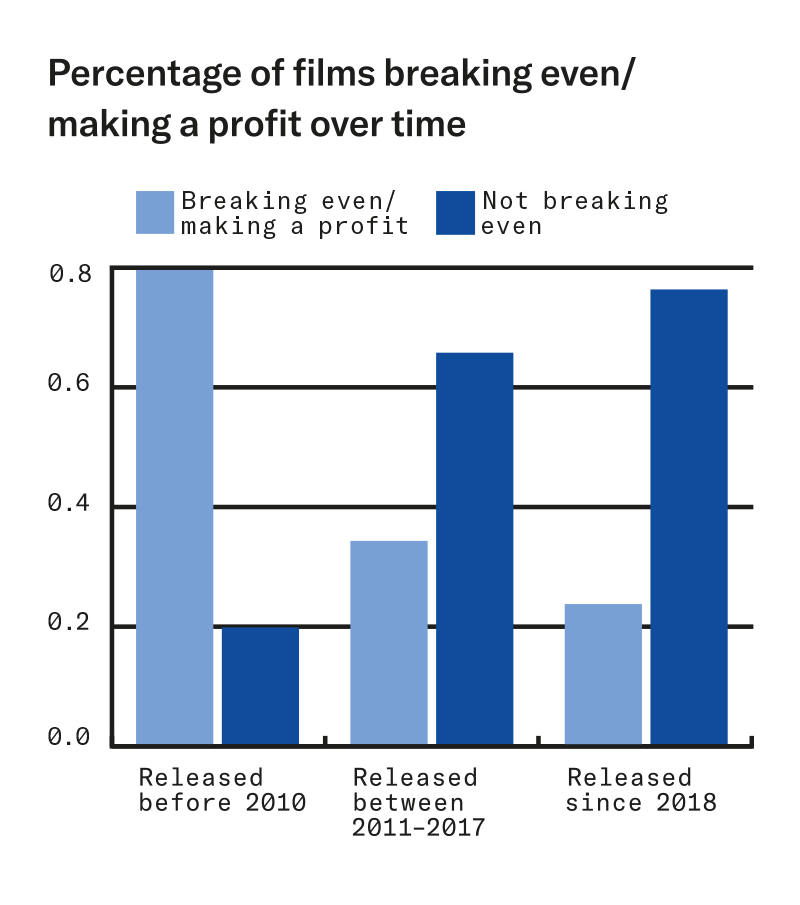

Yes, but, hasn’t it always been this way for independent films? Is it actually harder to break even/make a profit now than it has ever been?

Based on our data, the answer to the latter question is, resoundingly, yes.

Before 2011, which is about the time that streamers fundamentally changed the nature of revenue models, an independent film was substantially more likely to break even/make money. It became more difficult between 2011 and 2017 and has grown even more difficult since then. Until such time as a new model fundamentally changes the game—we can only hope in independent film’s favor—it is likely to become more and more difficult to break even/make a profit. The streamers will continue to consolidate and dominate the market, thus making the task of getting audiences to spend money on content elsewhere an ever-higher hurdle to clear. And unless current licensing revenue patterns change, it will remain difficult for filmmakers “lucky” enough to be acquired by those streaming platforms to recoup.

Do the data suggest any clear determinative factors outside of budget range as to whether or not a film manages to break even/make a profit?

By and large, it does not. We looked at the data through all sorts of lenses to see whether we could come up with any guiding principles. Factors that are often held up in conventional industry wisdom as strongly determinative of revenue outcomes, such as genre, actually offered no clear trends. In our sample set, dramas did not have particularly worse outcomes than genre films like horror or thrillers. And there were not clear trends as to revenue outcomes based on which platforms a film was released on—the most lucrative platforms for one film were catastrophes for another. The only real message to derive is what we have been telling our students and clients for years: Know your film’s audience, figure out on which platforms those viewers are watching films and get your films up there.

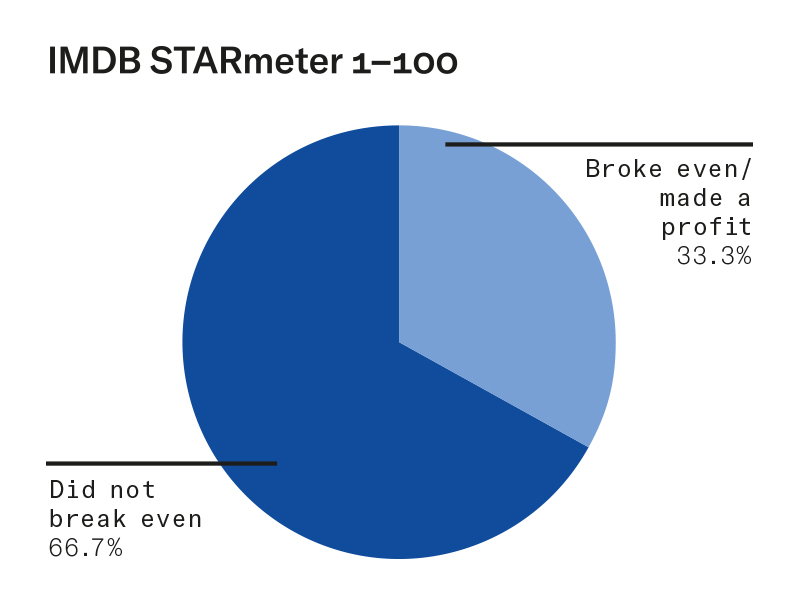

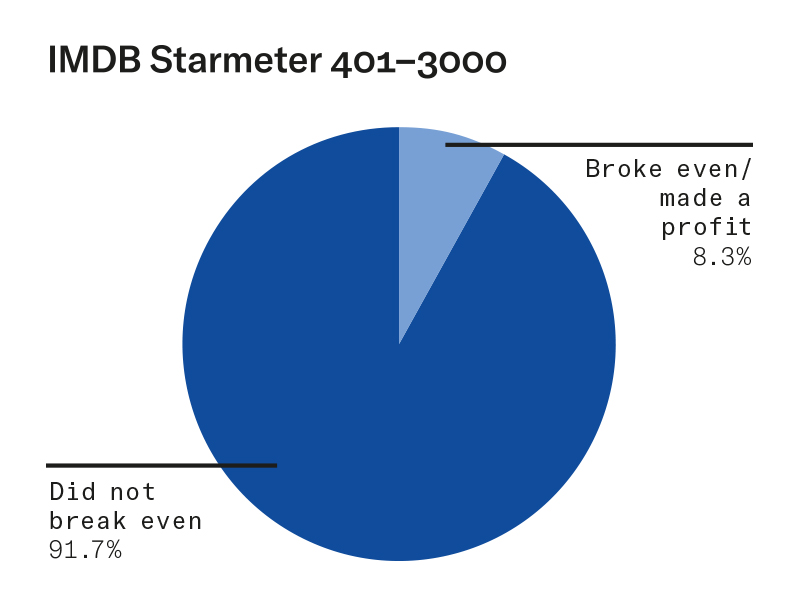

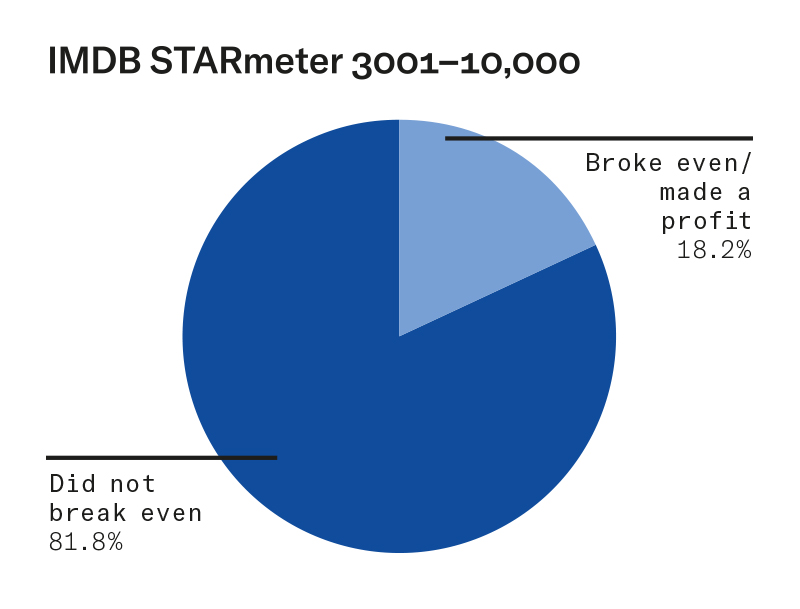

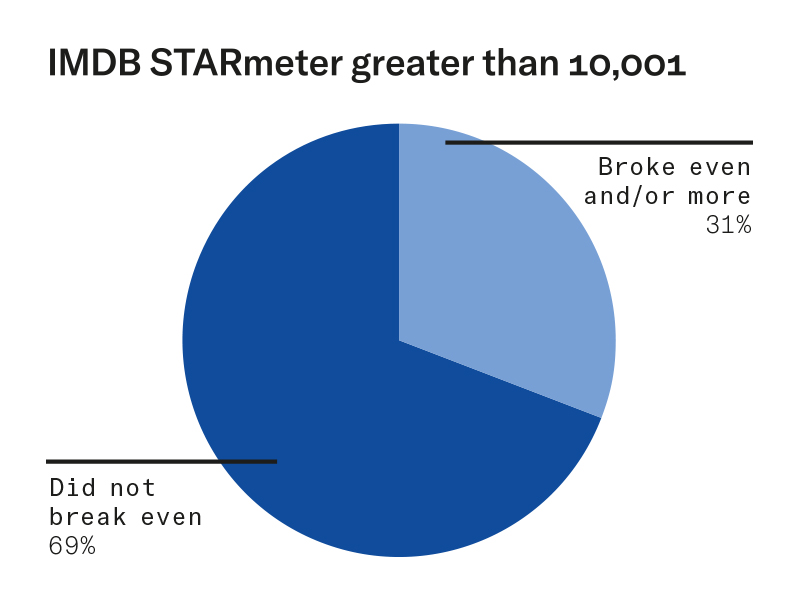

The one factor that did provide a clear trend was the good old, “How famous is your cast?” question, but not in the way that the industry tells us it will. To have some metric by which to measure how famous/well-known/recognizable the cast of a given film was, we had respondents tell us the current rank of their most well-known cast member on the IMDb STARmeter. The STARmeter is an imperfect measurement tool, but it allows for at least some kind of objective ranking system of actors. We consider the data only for films released since 2018 because it is reasonable to assume that this factor has changed with the shifts in revenue models, just like everything else.

How does having at least one famous cast member affect the likelihood that a film will break even/make a profit? (We did not receive any results of films with actors between 101 and 400 on the IMDB STARmeter.)

What is most notable in this data set is that, for the most part, the films that broke even/made a profit had actors at the highest and lowest ends of the STARmeter—in other words, had the most famous and the least famous actors. The films that did not break even/make a profit even had much more of a spread through the middle of the STARmeter, in addition to a high percentage in the lower range; in other words, they had either sort-of-famous actors or unknown actors.

We conclude—based on this data set only, of course—that a film’s best chance of making money/breaking even is to have extremely famous actors (ideally, in the 1 to 100 range of the STARmeter), or to have pretty much unknown actors (greater than 10,000). Having sort-of famous actors, for profitability purposes, seems to often be the worst case scenario.

This makes a great deal of sense from what we have experienced in our own films and observed in others but goes very much against the conventional wisdom most filmmakers are given (that having an at-all-famous actor is better than having an unknown actor). Our hypothesis is that there is a highly select group of actors at the top of the STARmeter who genuinely move the needle on whether or not an audience member decides to watch/rent/buy a movie—the kind of actor where an audience member will go, “Oh, they’re in it?! OK, I’ll watch.” However, we think the threshold for that, via the STARmeter, is very high and that only about the 100 most famous actors are in this category. The distributors and sales agents claim that a positive impact on viewership and revenue might extend to the top 500 or so most famous actors. Our data do not support or refute this, so for our analysis, we’ll stick to what we can extrapolate from our own statistics.

What we have observed is that many films start out trying to cast one of these 100 most famous actors and, when they fail to do so, begin working their way down the list by relative rank of “famousness/recognizability.” Often, they will end up casting an actor from somewhere between the 100 and 10,000 STARmeter range, for which they may be charged a rate substantially above SAG scale. Often these higher rates are negotiated by agents who are basing that actor’s “value” on their rate for another bigger budget film. That higher rate increases the independent film’s budget, but these actors do not actually increase sales of the film and thereby justify the budget increase. These films have worse profit outcomes than a film that simply cast talented actors who were willing to work for scale. (There are, of course, some well-known actors who do continue to work on independent films for scale rates plus back-end—many times for films that have golden elevator prestige elements.)

We are certainly not saying that casting entirely unknown actors is a guaranteed way to make money—it isn’t. In the most recent year’s data set, 48 percent of the films that did not break even/make money also had actors in the greater than 10,000 on the STARmeter. However, from a profit standpoint, unless you can cast one of the 100 most famous actors in the world, you are probably better off casting largely unknown actors.

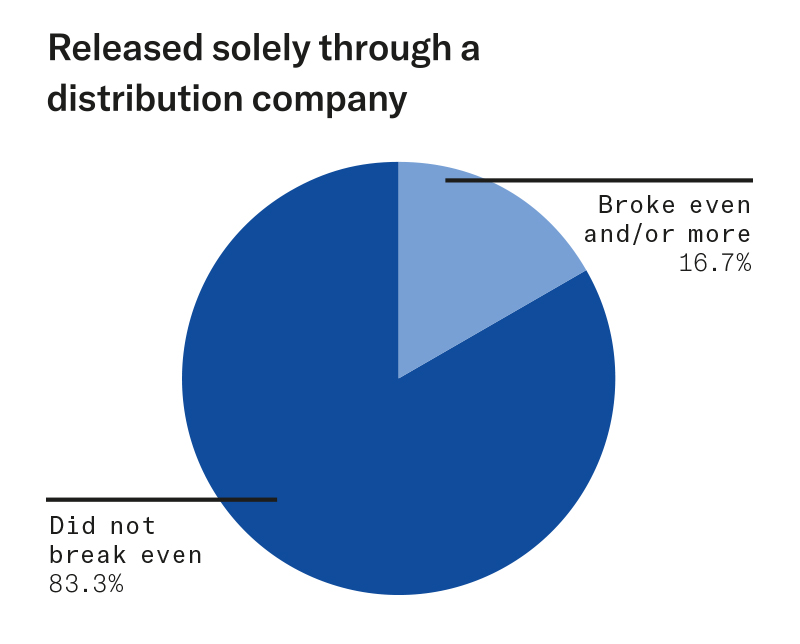

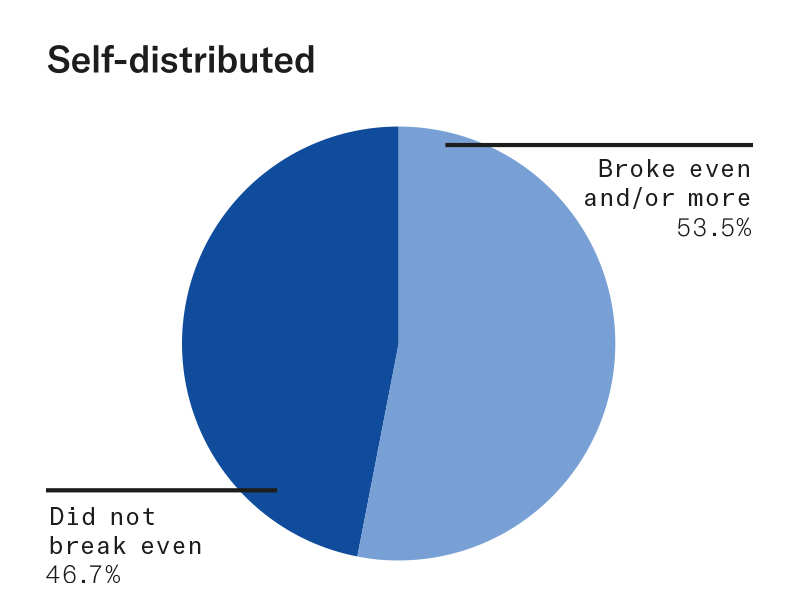

Is a film more likely to break even/make a profit if it is released through a distribution company or self-distributed by the filmmaker?

Limiting the data set once again to films released since 2018, we have broken the films down into three categories: those released solely through a distribution company, those that were self-distributed (this includes films who used a non-distributor third-party service, such as an aggregator, i.e., Filmhub or Quiver, until recently) and those that did a hybrid release, which combined elements of working with a distributor and self-distribution.

Based on our data set, if your goal is to break even/make money, your best bet is self-distribution (with or without a third-party aggregation service and if you are able/willing to devote the considerable time, money and energy involved). The majority of the films in our data set that released via this method broke even or made money. In our estimation, this may be because the decision to self-distribute often is coupled with the building of a team to design the film’s release, which almost always results in a more specific, resourced and focused marketing effort than a distribution company will likely have time for in the current oversaturated marketplace. Many of the smaller distribution companies right now are struggling with overworked staffs and business models that involve scraping together overhead costs from the dregs of profits accrued by releasing a large slate of films. Given the tough distribution numbers revealed by this study, significant attention should be paid to successes of self-distribution.

While you might make money releasing solely through a distributor, of the films in our data set that pursued this method of release, 83 percent did not break even. We can hypothesize that this is because of distributors taking marketing costs and fees off the top of a film’s gross revenue. Given the paltry revenues available right now for free-range films, it is possible that there simply isn’t room for a distributor in the revenue waterfall if the film is to break even or turn a profit. In the old days, distributors would often assume the risk on a film by paying a large (or at least reasonable) minimum guarantee (MG), allowing filmmakers to immediately recoup all or a portion of their films’ budgets. From smaller and even mid-range distributors today, robust MGs are vanishingly rare, meaning that a film continues to hold the risk, waiting to recoup out of overages that often never make it through the wall of marketing costs and fees.

(Interestingly, the method of release that resulted in the worst revenue outcomes in this data set was the hybrid release model. This may be a fluke in our data set or might point to some underlying truth. We can only speculate. This result may possibly reflect a lack of commitment to and focus on one distribution/revenue plan on the part of these filmmaking teams.)

Understanding all of this, we acknowledge that there is actual financial success and then there are the optics of success. Many filmmakers will decide to make the trade-off of accepting a financially lesser distribution deal if it means getting trade reviews and pull quotes they can insert in their bios. Others may choose different bottom lines over profit, such as a specific impact outcome for a mission-driven film. We ourselves are interested in a model of filmmaking that is actually financially sustainable over our careers so that we can continue making movies.

So strong is the mythology around the promise of golden outcomes awaiting filmmakers if only they work within the existing system that we often find filmmakers resisting a different approach. It can seem risky to take a gamble on an unknown, untested self-distribution strategy when we have been told that working within the system—say, releasing through a traditional distribution company—has in the past worked sometimes, for some people.

If you somehow manage to get a ride on the golden elevator of independent film during the development stage, bless you. Take that ticket and don’t get off until you arrive at the highest possible floor (although, Fair Play aside, the sales numbers for the 2023 Sundance films call into serious question how financially viable even golden elevator films remain). However, if you either choose, or are forced by necessity, to make a free-range film, it is far, far riskier monetarily to allow your film to drift blindly into the current model—bloating your budget with sort-of-famous actors, taking a deal with a distribution company because that feels shinier than going at it alone.

Given that the current model isn’t working, the least risky, most reasonable step is to learn from real data and to experiment radically and boldly to yield an as-yet-unimagined model that just might.

That’s what we are doing by teaming up with fellow filmmakers Elishia K. Constantine and Courtney Hope Thérond to develop a “filmmaker pod,” STORYMADE, which aims to be the new frontier of indie filmmaking: replicable, scalable, ethical and sustainable. Our four filmmaking teams will pool resources to create and distribute films together, attempting to bring down the overall costs of making and releasing our films. This model, we believe, will increase the likelihood of actually turning a profit—or at least making back our budgets so as to be able to pay for the next films and the films after that.

It is entirely possible that we won’t land on the right model this way. But we are fueled, as we hope you will be, by the understanding that few things could be less functional for independent filmmakers than the current model. So, it is in everyone’s interests to experiment radically and boldly, to share everything we learn with each other along the way, so that collectively, iteratively, we can unlock the next new model to sustain us.

Naomi and Liz will continue to collect revenue data over time in hopes that a larger sample size will reveal even better and more granular insights. If you would be willing to share actual revenue data from your feature film, please submit it anonymously.