Back to selection

Back to selection

True Crime Schedules and Teams

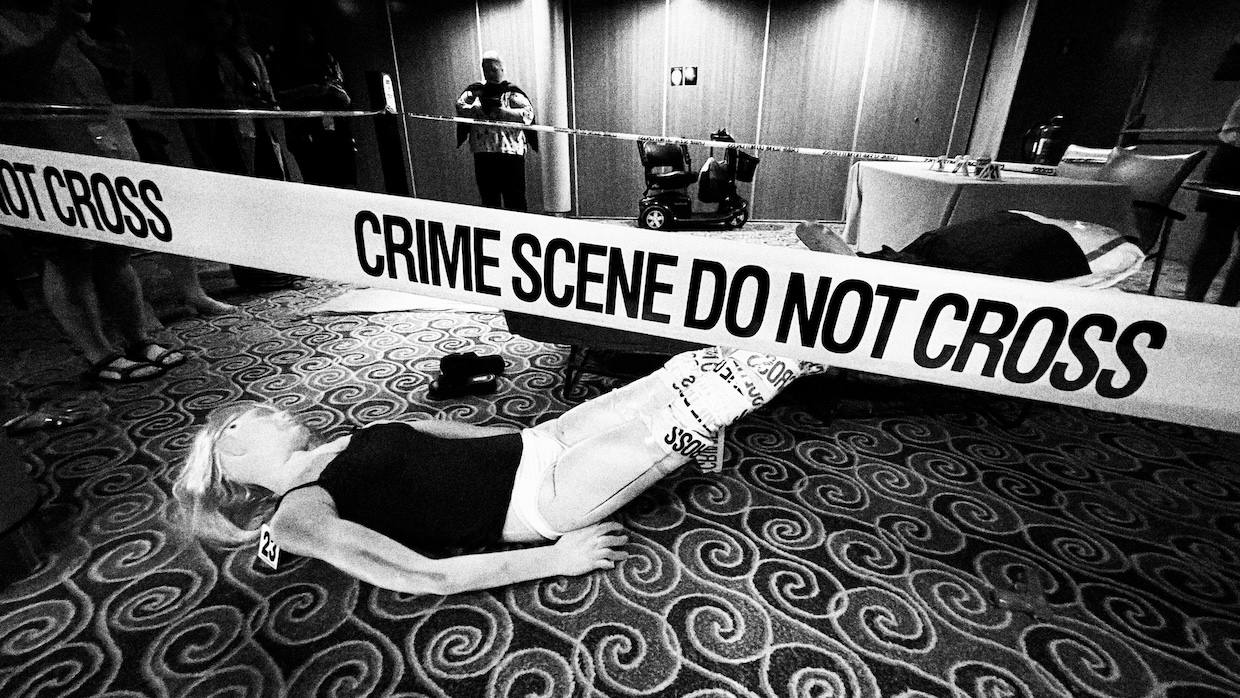

Aboard the CrimeCruise

Aboard the CrimeCruise The Alliance of Documentary Editors published scheduling guidelines that suggest one month per ten minutes of finished content as a reasonable editing timeline for the “average” documentary, with adjustments based on quantity of footage, team members’ experience levels and so on. For a single episode of a miniseries, the guide recommends “20 to 24 weeks for a full hour (60 min)” as a starting point. (I am a member of the organization but had no involvement in this paper.)

True crime editors report that, increasingly, edits are falling well short of those benchmarks, for reasons that are complex and reflect wider industry shifts. “Executives from the reality TV world have moved into the genre, and they do not appreciate the amount of time it takes,” according to a veteran editor I’ll call Alice. (Many editors asked to be anonymized while speaking candidly about working conditions; pseudonyms help distinguish among these voices.) “The problem with this is that reality TV is scripted; documentaries typically are not.” Frequent true crime editor Jen (a pseudonym) worked on a show that allotted only 10 to 12 weeks for each hour-long episode. Deadlines were so tight that she did not even have time to watch her own work before sending it off to network execs. Edward, an editor who asked to be identified by first name, described a Discovery ID series in which the schedule allowed only five weeks to rough cut and four more weeks to picture lock for a 45-minute episode. Such a timeline did not permit the editor to view all available footage. Unrealistic deadlines sometimes get extended, and those who have been through the rigmarole before know to take the stated schedule with a grain of salt—but newer editors with more to prove don’t necessarily have that liberty; they work overtime, without additional pay. “With your rushing and extra hours that you put in, you do end up giving them maybe a week of free work,” Jen estimated.

In an attempt to adhere to compressed schedules, a phalanx of editors, supervising editors, assistant editors and story producers is often jointly responsible for a task that, on a typical feature documentary, might once have fallen to only an editor and assistant. Larger series like The Vow and The Jinx often had “three or four editors working simultaneously,” according to supervising editor Richard Hankin, ACE, who remembered post-production creative meetings among “upwards of two dozen people on the Zoom call at any given time.” This is partly out of necessity: The sheer volume of footage on a documentary series can make the task impossible for a leaner team. Inbal Lessner, ACE, had to wrangle more than 1,000 hours of archival footage and roughly 200 hours of original footage on Escaping Twin Flames and hundreds of each on Seduced: Inside the NXIVM Cult—“more than any editor could watch, so you have to work as a team.”

The larger team demands greater coordination, as “the editor working on a particular episode may not have the context of what’s going on in the overall series,” said Hankin. The biggest adjustment for many editors is working with story producers, another role imported from reality television that remains rare in the feature documentary space. “At first, I was like, ‘Why do I want story producers?’” said Mia (pseudonym), an editor of a major cult series. “But it was too big of a project.” The directors, in that instance, “were totally against them. But at the same time, they were not really involved in the edit process.” Alice spoke of directors “dealing with the network, or the composer or the graphics team, or they’re working on other projects.” A story producer might work closely with an editor to craft a rough cut, conserving the director or showrunner’s attention for later in the feedback process—though Alice stressed that there are “no hard and fast rules” about the division of labor.

Despite the job title connotations of “producer,” the role is far from powerful. Edward characterized it as a cynical “means of getting really cheap labor” because story producers are often paid salaries comparable to assistant editors’ while shouldering much of the burden of footage review and selection, tasks editors no longer have time for. Constructing long “stringouts” of preferred footage, story producers hand over their sequences to editors whose job is more to reduce and finesse rather than construct. Limiting the responsibilities of the editor, in turn, provides streamers and networks with a further justification to squeeze schedules: “We budgeted for story producers. That means you need less time to do this.”

The role of the assistant editor within this organizational structure varies. In the days of 16mm film and flatbed editing machines, assistants were a constant presence in the editing room, apprenticing for a single editor. The confluence of the shift to digital, rise of remote work and grueling edit schedules has often relegated modern AEs to purely technical roles. Colin Fitzpatrick, an AE with credits on multiple premium docuseries, pointed to shows at major documentary production companies where assistants have become “their own separate technical department, servicing multiple editors” at once, an arrangement that originated in reality television. Sometimes, AEs will be spread across not only episodes of a single show but multiple shows at once. The volume of necessary technical work—ingesting footage, exporting cuts, preparing stringouts—leaves little room for flexing creative muscles.

These larger teams have become a way of coping with what editor Drew Blatman called “fast and furious” deadlines imposed by streamers. Another editor, Christopher Walker, described a dysfunctional project with “a lot of editor turnover. It quickly became this frantic all-the-time energy, which I cannot work in. I could feel the energy through Slack.” The erosion of editorial control has been one of the disappointments for editors like Christopher Passig. “I’ve been in situations—and to be fair, not just in true crime—where there isn’t time or money budgeted for the editor to watch the material. The assistant editors and story producers are the ones watching the footage. They’re pulling selects. They’re effectively writing the show.”

The factory-like approach to the editing process might offer only the illusion of efficiency. On some shows, in Jen’s experience, one editor-story producer team will be responsible for reaching a rough cut with an episode; another will take over to finish it, incorporating feedback from the network. But because the incoming team has no familiarity with the episode or the raw footage, this can be a counterproductive approach, with little continuity or cohesion. She summed up the networks’ attitude: “It’s a formula. We can do this quicker; just throw more people at it.”

Established editors can sometimes find ways to maintain greater creative freedom. For Passig, Telemarketers was a high point: “Aside from some help at the assembly stage, I was fortunate enough to be the sole editor across the series, which feels rare and was hugely helpful.” On Last Call, Walker found that the schedule “actually did give me time to explore the material because we were trying to do something a bit different. It was a really nice change of pace.” Amid an industry impatient for content, reasonable schedules and creative authorship aren’t a given; defending them requires concerted efforts from producers and directors.