Back to selection

Back to selection

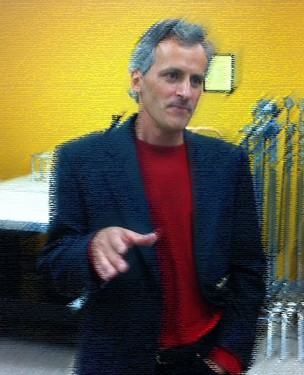

Documentary Production at Frontline: An Interview with Tim Mangini

Tim Mangini is the Director of Broadcast for WGBH’s Frontline. His overarching role is to make sure the programs get made and that they get made on time, on budget, and that the quality level meets Frontline’s expectations. Tim began his career working in animation and sound in Hollywood, then came back to Boston and worked in the corporate and broadcast video world before joining WGBH in 1995 as a post-production supervisor.

Tim Mangini is the Director of Broadcast for WGBH’s Frontline. His overarching role is to make sure the programs get made and that they get made on time, on budget, and that the quality level meets Frontline’s expectations. Tim began his career working in animation and sound in Hollywood, then came back to Boston and worked in the corporate and broadcast video world before joining WGBH in 1995 as a post-production supervisor.

One of his roles as Director of Broadcast is to work with producers to identify the equipment they need to capture their vision. We recently spoke to him about production, and shooting for Frontline:

Filmmaker: What’s your relationship with the producers?

Mangini: When they are given a project for Frontline, it’s written into their contract that they give us a call and that we discuss the technology that they’ll use for acquisition and for post-production.

If they’re doing sit-down interviews with members of the Senate, that possibly dictates one set of parameters. If they’re going out in the field in Afghanistan, that might dictate a completely different set of technologies. We have discussions with them about cameras, people, how many crew, how much lighting, and all the different parameters that are going to be involved in their locations acquisition. We also talk to them about post-production and how the will edit it.

Then as the producers work on their projects, I speak to them if they hit problems, or maybe they need an unexpected camera rental, or they want to use a camera that I don’t generally like and they want to get permission to be able to use that.

Filmmaker: Who are these producers?

Mangini: Most of the producers for Frontline are not staff producers. They are independent producers that we hire to do work for us. Many of them we’ve been working with for several years. They work out of New York or California or London or Chicago, and we contract with them independently.

Filmmaker: What’s the most common camera that they’re shooting with? Is that a fair question?

Mangini: I answer that question with “yes.” Years ago we actually tried to limit the cameras, and the senior staff, the executive producers, came in and said, “We want people to be able to do whatever the hell they want to do. If they see a vision that they want to achieve, and they can only achieve it with a certain kind of camera, we don’t want to limit that.” And that’s true to form for us. We really strive to help the director and the d.p. achieve their vision in every way, shape or form.

Filmmaker: So you don’t recommend cameras?

Mangini: Along the way we’ve certainly learned a lot about different types of cameras, and what they do and what they don’t do well. It’s hard for us to put together a set of cameras that you can or cannot use, but we do have leanings.

We really try and maximize the form factor, sensor size, and workflow to what people are doing, and what their capabilities are. We have some producers and teams who are not that technically savvy. You don’t want them to be having to be doing huge amounts of data wrangling in a difficult location. To those producers we highly recommend they use tape. They shoot the tape, stick it in a box and bring it back. But there are producers who are producer/director/shooters who do everything and really understand the technology, and for them, having backups of backups of backups is normal.

We try and fit the camera system and the acquisition system to the actual circumstance as much as anything.

Filmmaker: How did Frontline start using DSLRs?

Mangini: I remember distinctly one of our first experiences: I was awoken at 3am by a call from Afghanistan, and my producer was saying, “You won’t believe it, I’ve just seen the most amazing footage come back from the front from this thing called the Canon 5D. It’s the most amazing footage I’ve ever seen. We want to use it on our shoot, we’re getting on a helicopter in six hours to be embedded. Can we use that camera?”

I give the producer/director a huge amount of credit for actually giving me the call. Overnight I did some research and I called them back and I said, “Here’s what I can tell you; the sensor is extraordinary, it’s going to give you really shallow depth-of-field and great low-light performance. It’s going to give you great mobility and it’s going to get you shots that you otherwise can’t achieve in the field with the small cameras we’ve sent you out with. That’s the good side. The bad side, the workflow is going to be a living hell for you and for me, so I would prefer that you not use it. If you feel like it’s important to achieve the vision that you want to achieve, shoot with it but be circumspect about getting things that you absolutely have to have.”

Ultimately, they shot a portion of the film with the 5D and I think we had a four-minute section of the film shot on that camera. I think it took us something like three hours to ingest the four minutes. This was in the early days in that process, so things have gotten a lot better since then.

Filmmaker: What cameras are you encouraging now?

Mangini: We encourage people to try and stick to cameras that have relatively small form factors, have good sensors with good low-light capabilities, and most importantly, their workflow is predictable. The workflow’s getting better all the time.

Of late we are big fans of the Sony PMW-F3 and the Canon C300. They fit in our wheelhouse because they are what I’d call low-to-modest cost cameras, but you get a lot of bang for the buck. They have workflows that are ubiquitous; you can use them on any editing system relatively easily. It’s common for our shooters to be carrying a C300 and have a Canon 5D or a 7D as the reversal camera. Or they might use the C300 or a PMW-F3 as a wide shot, and then use a Sony PDW-F800 shooting XDCAM 4:2:2 50 Mbps as the tight shot, and then use the 5D as the reversal. That’s fairly common.

We still see some tape, but just in the last three years it has gone from being 100% to closer to 10% of what we online here.

Filmmaker: But you prefer tape?

Mangini: The big issue for us was not going from standard def to high def, because the workflow was the same: you’re going from tape to tape. There’s part of me that’s an old fuddy-duddy that says tape is good. Tape is so darned easy. For those that have only worked in the file-based world and only know that, maybe that seems strange because file-based can be quite convenient. But when you work on very tight deadlines, in a shared environment where multiple people need to be working on things at the same time, working with file-based cameras, particularly in the early days of the file-based revolution, were fraught with danger.